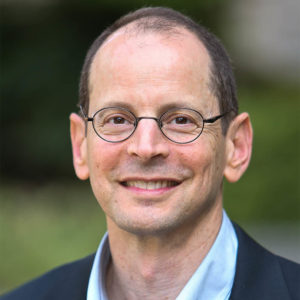

David Blankenhorn + Jonathan Rauch

The Future of Marriage

What would it take to make our national encounter with gay marriage redemptive rather than divisive? David Blankenhorn and Jonathan Rauch came to the gay marriage debate from very different directions — but with a shared concern about the institution of marriage. Now, they’re pursuing a different way for all of us to grapple with the future of marriage, redefined. They model a fresh way forward as the subject of same-sex marriage is before the Supreme Court.

Image by Paula Keller, © All Rights Reserved.

Guests

Jonathan Rauch is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and co-director of The Marriage Opportunity Council. He's a contributing editor to The Atlantic and National Journal, and the author of Gay Marriage: Why It Is Good for Gays, Good for Straights, and Good for America.

David Blankenhorn is founder and president of the Institute of American Values. He's also co-director of The Marriage Opportunity Council. His books include The Future of Marriage.

Transcript

April 16, 2015

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: David Blankenhorn and Jonathan Rauch came to the gay marriage debate from the predictable opposing sides — but both as long-time advocates of the institution of marriage. Now, they’re pursuing a different way for all of us to grapple with the future of marriage, redefined. We experience the redemptive conversation they model as the subject of same-sex marriage is before the Supreme Court.

DAVID BLANKENHORN: We called what we did achieving disagreement.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, I like that.

MR. BLANKENHORN: See, because it’s easy to have a false disagreement. I can just say, “Oh, you’re a bad person and you’re stupid.” But to actually know where we disagree requires effort from you and from me. We have to have a relationship to do that. And that, I’ll tell you, in today’s world of hyperpolarization and the sheer idiocy that is our public debate, the heart just cries out for this kind of serious effort to achieve disagreement.

JONATHAN RAUCH: I believe there’s an element of patriotism about this, and I saw in you someone who is willing to say being right is not as important to me as making a pact with my fellow Americans on the other side so that we can share this country.

MR. BLANKENHORN: We can live together.

MS. TIPPETT: “The Future of Marriage.” I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

MS. TIPPETT: I interviewed Jonathan Rauch and David Blankenhorn before a live audience at the Humphrey School of Public Affairs in Minnesota in 2012.

[applause]

MS. TIPPETT: A question on which we focus and fight is that of legalizing gay marriage. We’re going to make that question subordinate this hour to a broader reality that, in 2012, a majority of Americans, across our partisan and religious divides, favor some kind of legal and social recognition for gay couples.

In his 2007 book, The Future of Marriage, even as David Blankenhorn argued against gay marriage as a social good, he wondered, “What would it take for our collective confrontation with this issue to become redemptive rather than divisive?”

I love that question, and it’s a guiding question I’d like to stay close to in the discussion we’re about to have. It’s a question both Jonathan Rauch and David Blankenhorn have pursued even when they’ve disagreed across the years and as they’ve each evolved their own positions, their public voices, and their roles in their communities. From very different directions, at times, they’ve argued that this is a moment of opportunity for all of us, gay and straight, liberal and conservative, to reexamine the deepest meaning of marriage.

Jonathan Rauch is a lifelong journalist and also a gay man who believes that marriage equality for gays and lesbians can strengthen the value of institutional marriage for everyone. He honors the sanctity and social sense of this tradition, as he’s known to complain, “more than many of the straight people he talks to.” David Blankenhorn became known in the words of the prominent gay writer Andrew Sullivan, as “the most intellectually honest, non-homophobic opponent of marriage equality.”

David Blankenhorn testified against gay marriage in California’s tumultuous Proposition 8 debate. But in the summer of 2012, he announced a change of direction. “My intention is to try something new,” he wrote in The New York Times. “Instead of fighting gay marriage, I’d like to help build new coalitions bringing together gays who want to strengthen marriage with straight people who want to do the same.” Their friendship is, I think, a model of that coalition, so let’s explore it. And I want to start with you, Jonathan. Where did you grow up, by the way?

MR. RAUCH: Phoenix, Arizona.

MS. TIPPETT: OK. So I wonder if you would tell a story that you write about of this vivid memory that stays with you from childhood when you had, as you describe it, this realization that the institution of marriage was not there for you.

MR. RAUCH: I still remember. I’m sitting on a piano bench. I’m maybe 10, 9 — 10, and I understand that, for some reason, I’ll never be able to get married and have a family. And I don’t know why that is, but I know I’m different. Years before I know I’m gay, I know that this destination for my love won’t be there for me.

MS. TIPPETT: And you take your readers in your book on gay marriage through this thought experiment. What if you woke up one day and marriage didn’t exist anymore?

MR. RAUCH: Yeah, yeah. When I talk about this, I try to always start there with the moral imagination of asking people — most of you people here, you’re straight. A lot of you are married. Imagine that your marriage went away, and I don’t mean that you got divorced. I mean that you never got married, never could marry, never had the prospect to marry. You know, when you’re eight or nine or 12, the first kiss, the first crush, the first date, all of this is leading to family formation and marriage and a home, and you don’t have any of that. And imagine how much more barren your life is, and that’s what that was like.

Here’s a story that’s not in the book. So I’m 25, and I’m on the verge of finally acknowledging to myself and the world that I’m gay, after all those years of twisting and tormenting myself to deny it. I remember I’m in the kitchen, actually, cleaning the floor. It’s always something trivial, isn’t it? I’m thinking to myself, “I don’t want to be gay, I don’t want to be gay, I don’t want to be gay.” And the reason for that is not that I am homophobic or anti-gay. It’s that it’s 1985, and being gay means I’m condemned to a world, I think, of anonymous sex and late-night bars and poppers and AIDS and early death. And that’s not what I wanted.

MS. TIPPETT: So, David, you were born in Jackson, Mississippi. I wonder how you would trace the earliest routes of your imagination about marriage, but also your civilizational imagination, if we want to follow on how Jonathan is putting those things together.

MR. BLANKENHORN: I was born in 1955, so the big thing for me was the Civil Rights Movement growing up in the South. That was the kind of morally paradigmatic experience for me. I think it kind of shaped a lot. That, and the little church I grew up in, the little Presbyterian church. Marriage, I took for granted. I didn’t know — I don’t think I knew anybody whose parents were divorced. I had no concept about anything about gay anything except to learn ugly words, a few ugly words. I didn’t really understand.

MS. TIPPETT: And then you’ve also talked about being formed by your work as a VISTA volunteer a little bit later on in early adulthood. And that was a moment, I think, where you started to think about families, right?

MR. BLANKENHORN: Yeah. I was coming out of the South and thinking a lot about the Civil Rights Movement as a kind of a model for me. I wanted to — I was a VISTA volunteer, and then I spent five years as a community organizer in Virginia and in Massachusetts. And, oh, it was kind of the Saul Alinsky model of community organizing. So we were always picketing City Hall because there weren’t enough city service deliveries in poor neighborhoods, or we were fussing at the utility company executives because the utility rates were too high.

But if you live in poor communities, and these are your friends and neighbors and the people you’re working with every day, I was struck by the kind of hollowing out of the civil society and so many children growing up without fathers. So that’s what really got me interested in the subject of the role of men in families and the role of marriage. That’s what turned it for me.

MS. TIPPETT: So a story that I didn’t really know until I started reading about your work and your history is that, especially in the ’80s and ’90s, there was a flood of research and you became part of that research and writing and thinking about how marriage matters, how intact families matter. So there was this movement to support the flourishing of marriage and also to work against what felt to you like a movement, an idea that fathers were superfluous or disposable. You founded the Institute for American Values in 1987, you helped found the National Fatherhood Initiative in 1994. And that was happening and it was big and there were a lot of people involved in it. And then the issue of gay marriage kind of landed in the middle of that.

MR. BLANKENHORN: Yeah. That was the time for me, during that period of time in the late ’80s and ’90s, and that was the time when I was just wandering around the country speaking. And I was like a fatherhood jukebox, you know? You didn’t even have to put a nickel in. I would just give you a talk about how children needed their fathers and that father absence was the biggest problem of our generation because it was the problem driving all the other problems. My son used to come with me, and now he’s started mimicking me. He would say, “We are living in an increasingly fatherless society.”

[laughter]

MR. BLANKENHORN: He would — because like — he had this — he knew this speech as well as I did. And marriage is the way that connects men to fatherhood, because mothers and their children, there is such a bond between the mother and child. The mother doesn’t need anyone’s permission. The mother doesn’t have to audition for this role. She has it, she claims it, it’s the strongest bond in the human species.

MS. TIPPETT: She doesn’t get to audition either. She just…

[laughter]

MR. BLANKENHORN: Right, right. But fathers are different. Fathers need the cooperation of the mother to be a father. And the way we do that is we have that arrangement, it’s called marriage. And so I was a fatherhood nut, and then I was a marriage nut. And we weren’t giving a single thought to gay anything. This was just what we were doing, trying to strengthen this institution that protected children. So when the gay marriage issue came along, I first tried to avoid it. I spent years not trying to talk about it because I knew it was divisive. And I didn’t want to — it seemed like a side issue. I didn’t take it that seriously. Eventually, in the early 2000s, I got drawn into it a bit, got all tangled up when I met Jonathan because he invited me to come talk when his book came out in 2005…?

MR. RAUCH: 2004.

MR. BLANKENHORN: 2004. He invited me to come give a talk. We didn’t know each other. I had met him. I read the book. And I thought I was going to give a rational calm presentation, but I found myself just being overcome with emotion. And I said many ugly things about him and the book and accused him of bad faith and cited all these radical gay writers and said that this is what his real agenda was. It was an un — it was not by best day.

[laughter]

MR. BLANKENHORN: So — but…

MS. TIPPETT: Why do you think it worked that emotion in you?

MR. BLANKENHORN: I don’t know. I still don’t know.

MS. TIPPETT: I haven’t read anything about that.

MR. BLANKENHORN: It just kind of poured out. I called him the next day. I said I was sorry. I said I really regret having acted this way. He was like, “Oh, OK.”

[laughter]

MR. RAUCH: I’d been in Washington a long time, and I’d never gotten a call from someone saying, “I’m sorry I was intemperate. That wasn’t my best day.”

[laughter]

MS. TIPPETT: You’d had emotional outburst, right. I mean, so what’s striking to me is — what’s interesting as I read the two of you across time, I mean, Jonathan, the idea that marriage is a bedrock of civilization, that it’s good, that’s it’s honored and encouraged by religious and moral traditions, has always been also your strongest argument for gay marriage.

MR. RAUCH: Yeah. David and I had this cobra-mongoose relationship partly because we were coming from the same place. I had covered economic policy in Washington in the ’80s and began to listen to a growing number of people who were saying the problems of poverty and crime and inequality and fragile societies are largely tracing back to family breakup. And I became a marriage advocate, actually, before I became a gay marriage advocate, because I began to see that this institution is how we form and create the many societies on which the larger societies depend.

So along comes Andrew Sullivan in 1992, I guess it was. I hadn’t given a thought to gay marriage because it wasn’t on the radar. It seemed outlandish at that point. And the minute I read that article, I said I knew that’s it. That’s the answer for the gay community, which is struggling with all the same kinds of problems you see in any community which doesn’t have family and marriage. And this can strengthen marriage. Here we have new recruits to this institution. It’s going to help shore the thing up. I saw a win-win, and that’s how I came at it, but at the same values that’s guiding David.

MS. TIPPETT: And you have said that, as you went out talking to audiences, the people you ended up lecturing about the value of marriage as an institution we’re the straight people in the audience.

MR. RAUCH: Yeah. I mean, you straight people out there, I mean, you broke it. You’re going to have to fix it. We didn’t break it.

MR. BLANKENHORN: You just haven’t had enough time yet. [laughter]

MR. RAUCH: Yeah, we’ll work on that, but you know…

MS. TIPPETT: So I should say, my favorite New Yorker cartoon about this was clearly the old married couple sitting reading and the wife says to the husband, “Oh, look, gay people will be allowed to get married now.” And the husband says, “Oh, dear, haven’t those people suffered enough already?”

[laughter]

MR. RAUCH: Well, that’s what Irving Kristol said when he heard about it. He said, “Let them have it, they won’t like it.”

[laughter]

MR. RAUCH: But, I mean, you guys are going to have to fix it. And we can actually, I believe, help fix it by trying to set good examples and creating more social capital and more marriages for society. But in order for you to fix it, you’re going to have to realize that this is not just a private contract between two individuals. When I talk to young people on college campuses, they all think marriage is — it’s a thing two people do. And if they need a piece of paper from the state, that’s just a convenience. I tell them, no, no, no, no. Maybe you have to be gay to see this, what it’s like to be excluded from a community and all the tools that go with this, but this is an institution.

This is a commitment that two people make, not just with either other, but with their community. And that commitment is to have and to hold from this day forward, for better or for worse, for richer or for poorer, in sickness and health, till death do we part. That’s a promise you as a couple are giving to care for each other and your children forever to your whole community, and the community has a stake in it. And that’s what we gay people want. We want to be married in the eyes of community, in that web of family.

MR. BLANKENHORN: Well, but may I remind you that you may be able to do all those good things, but one thing you can’t do is, if you have children, you can’t be a home where that child is being raised by the mother and father whose bodies created the child. That’s the one thing you can’t do.

MR. RAUCH: Correct.

MR. BLANKENHORN: So I accept all the things you say about, especially you and people who are approaching the issue like you, “Let us in. We can strengthen this institution. We have a higher level of idealism than a lot of you straight people.” I hear it all, I really do. But there’s issue of filiation, of the protection of the child by uniting these three strands of the parent relationship — the biological, the legal and the social — that cannot be done in a same-sex relationship. So the reason I was against gay marriage for all those years that we were arguing about it was primarily that reason. For me, that’s been the nut of it.

MR. RAUCH: Yeah, and I never got that. I mean, it seemed to me we’re infertile couples like millions of straight infertile couples, and no one says they shouldn’t get married because they can’t provide a biological mother and father…

MR. BLANKENHORN: No, no, I didn’t say that. I didn’t…

MR. RAUCH: I don’t want to re-litigate all that now.

MR. BLANKENHORN: You don’t want to re-litigate, all right.

MR. RAUCH: I’m just making the broader point that I heard your argument. I never really understood it. From my point of view, it’s simpler than that. Kids need married mothers and fathers, and the way you get that in society is by encouraging everyone to get married, and I thought we were contributing to that. So we never really communicated about that point. I don’t think we ever crossed that synapse.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, “The Future of Marriage.” We’re at the Humphrey School of Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota. I’m with David Blankenhorn, president of the Institute for American Values, and Jonathan Rauch, a journalist and guest scholar at the Brookings Institution.

So, David, you have concerns and you have discomfort and that makes you like a lot of people, a lot of good people. But you did have a change of heart and a change of approach. And I wonder if you would talk about how that happened.

MR. BLANKENHORN: It’s hard for me to put my finger on it because, for me, it was a process of thinking this and thinking that and having this conversation and having that conversation. And then one day I woke up and I realized by the time someone challenged me to say whether or not I had changed my mind, I really realized I had already without really being conscious about it. Some of it, I think, if I had to make an intellectual argument, I grew in my feeling of the importance of accepting gay and lesbian people as equal members of the society. I grew in my recognition of the prejudice that has existed and continues to exist, including in me.

I came to realize that the radicals that wrote the books about queer theory and so forth were different than many of the ordinary gay and lesbian couples who were just living their lives and weren’t that different in most respects than heterosexual couples. I saw an emerging consensus in the society — particularly among the elites and younger people — that was meaningful to me. I was a marriage advocate, and I saw, after 10 or whatever many years of fighting this issue, that the trends in the society at large were not improving.

We’re in this funny situation. We’ve got, what, 2 or 3 percent of the population, a tiny number of Americans, who are sincerely saying, “Let us in this institution. This means everything to us.” Meanwhile, the vast majority of Americans are exiting the institution quickly. If you go to Middle America now, blue-collar America, working-class America, you will find marriage in shambles.

So it’s weird. It’s like the people that want in, we say no, and the people that are already in — like, we are just rushing out. And I was their Mr. Anti-Gay Marriage. How is this helping strengthen what really matters to me? And the answer is, it wasn’t. It wasn’t. If fighting gay marriage was going to get heteros to recommit to the institution, we would have seen a sign by now, I think.

[laughter]

MR. BLANKENHORN: But it wasn’t happening. And the other thing — and then I’ll stop — is that I wanted to have a debate about marriage. I wanted to debate the very thing that Jonathan’s still saying he doesn’t quite — what are you really talking about? This biological — you know. Well, it mattered a lot to me, and I wanted to have a big debate about it. It’s not happening. Most heterosexual Americans believe that marriage, as you point out, the notion of marriage is private ordering. The notion of marriage is just someone you love.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. I mean, I think this is clear, but I want to say for a second. For neither one of you is the case for marriage about two people loving each other, just falling in love.

MR. RAUCH: Correct.

MR. BLANKENHORN: Well, that’s the reason we were able to, I think, develop an intellectual respect and then, I think, a friendship was because we both had that fundamental conviction of wanting to strengthen the institution of marriage. And the other thing I’ll say, I mean, I don’t want to get schmaltzy about it, but the truth is…

MR. RAUCH: Oh, go ahead.

[laughter]

MR. BLANKENHORN: There’s the intellectual — you think, you read, you sit in your study, and you try to think about the correct view. But the truth is that I probably wouldn’t have changed my mind without knowing Jonathan personally. And I used to think, well, oh, gee, what a lame thing. Your friendships are influencing your thinking.

[laughter]

MR. BLANKENHORN: But, I — you build up a kind of a barriers of belief in theory, and it keeps the other people out, and so you talk about them. You have theories about them. You can explain their lives to them, but you never really talk to them and see it from their point of view. So for me, as this guy from the South, older guy, hadn’t known many gay people, so it was a meaningful thing. And after being very aggressive and abusive, he responded with kindness and like, “Uh, well, maybe we could talk a little bit.”

So we ended up writing some articles together. We ended up co-chairing a project that we called Achieving Disagreement where people from both sides bring together. We co-chaired that. So it sounds lame, but honestly, it was the personal relationships with Jon and a few other people that kind of caused me to say, “Try something new here. Try a new approach. It’s OK to change your mind on this and try a new strategy.”

MS. TIPPETT: Jonathan, you have written something, which I think is pretty unique, that you also see this consensus. And you say that, in a sense, the idea of gay rights has majority status now in terms of its support in the population, and that this changes — this puts a new burden of responsibility on gay members of society. You said, “[We] have won the central argument” and “we must change.” That now is the time to “bend towards accommodation” when you “can live with the costs.”

MR. RAUCH: Yeah. This is my other more recent campaign and, to be honest, I don’t expect to be as successful with it as we’ve been with marriage, but I’m trying anyway.

MR. BLANKENHORN: Well, if you’re not, I’m screwed, man.

[laughter]

MR. RAUCH: Yeah, here’s one for you, Dave.

[laughter]

MR. RAUCH: So gay people were the victims of majority intolerance for many, many decades. And public opinion in America is a ferocious thing. Tocqueville wrote about it — “Tyranny of the Majority,” he called it. Something very, very important happened around 2009. The Gallup poll, for the first time, showed a tie in people saying homosexual relationships were morally acceptable with people saying they were not morally acceptable. And the lines have now crossed. There is now — I think it’s like a 9 or 10-point gap of a solid majority of Americans saying it’s OK to be gay. So this is new. This means we’re now the moral majority.

This means the burden of proof is now on the other side. And this means it’s going to be tempting for gay people to press our advantage and try to use the law to make it difficult for people who want to preserve religious traditions that are anti-gay to do so. And we have good reason for that. We have suffered very directly and very concretely and quite often with our lives from religious bigotry. It’s not to say all religion is bigotry. So it is very tempting for us to say, “Let’s drive this out of society altogether. All forms of discrimination, whether religious or not, should be illegal.” And I’m saying to gay people, no, we’ve got to share the country.

There is a thing called the First Amendment, religious liberty. We’ll get squashed like bugs on the windshield if we try to go against religious liberty. But more important, we want to be in a live-and-let-live society where no one gets treated as a prisoner of conscience and feels the need to stay in the closet, frightened because of what they believe. That’s what we fought against all those years, long before marriage, and that’s what we will continue to fight against. And that’s why we need to be champions of all reasonable protections for religious people who may not agree with us and may not want to associate with us, but we need to let them share this country with us.

MS. TIPPETT: And you have also called out the danger of throwing around charges of bigotry promiscuously.

MR. RAUCH: Yeah. I mean, there are bigots and I’ve encountered them and I can tell you the stories. But the great revelation in me, Krista, of being involved in gay marriage since now 1996 when I first came out for it — excuse the expression — is that most Americans, even most anti-gay Americans, are not fundamentally bigoted or hostile. They’re not evil; they’re blind. And our job is to help them see.

It doesn’t help to call them bigots even when they are, but usually they’re not. Usually they’re not. Usually, they need to understand us better and go through something like a process kind of like what David’s been through. It doesn’t mean they’ll come out where we come out, but you would be amazed at how open Americans can be over time and how responsive the conscience of this country is.

MR. BLANKENHORN: It’s a good point.

[music: “Night in the Draw” by Balmorhea]

MS. TIPPETT: You can watch, listen, and download my conversation with Jonathan Rauch and David Blankenhorn at onbeing.org. This was the third of four Civil Conversations events we held in broadcast in 2012 to subvert deep divides in American life. A great group of policy centers joined us: the Humphrey School of Public Affairs, the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics, and the Brookings Institution. You can learn more and add your voice to this ongoing initiative at civilconversationsproject.org. I’m Krista Tippett. On Being continues in a moment.

[music: “Night in the Draw” by Balmorhea]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, a dialogue that breaks new ground on the future of marriage and on how we might navigate other difficult territories of our time, across our differences.

Jonathan Rauch is a journalist, a scholar, and a gay man. He shares socially conservative concerns about marriage and wants them taken seriously. David Blankenhorn is a longtime family and marriage advocate. He testified against gay marriage during California’s Prop. 8 debate. But in 2012, he announced that he was dropping his legal opposition to gay marriage. He cited an emerging moral consensus in American society. And he described his intention to work together with gay and lesbian people now to make their marriages work for the good of children, families, and society as a whole.

MS. TIPPETT: I want to talk a little bit about this word “civility” and what you’ve both learned about it because, I mean, we’re driving at that now. I mean, David, you’re in the unique position of having been on both sides of being labeled.

MR. BLANKENHORN: Having thoroughly angered everyone at least once.

[laughter]

MS. TIPPETT: You wrote on your website, on your blog, about the relationship between civility and doubt. I’d love for you to say some more about that.

MR. BLANKENHORN: It’s funny that you would ask that. It’s the thing I’ve been thinking about most in the last several months, more than any other topic. And I think that doubt and civility are friends. They go together kind of like coffee and cream. They’re partners. By civility, I mean treating the other person the way you would want them to treat you. And by doubt, I mean believing that you may not be right even when your position is passionately held.

MS. TIPPETT: You wrote this: “What I need as a doubting person is the wisdom of the other.”

MR. BLANKENHORN: See, because if I don’t have any doubt, I don’t need you. I should be nice to you out of manners, but I don’t need a relationship with you. I may want you to be available to be lectured by me so that you can come to the correct view. And I may want to treat you politely for that reason, but I don’t really need you. As I grow older, I grow in doubt. And that’s good. And I feel like that’s a healthier way to be. And if I am not sure that I have the full truth of the matter, I need you.

Civility allows me to have a relationship with you. It feeds me what I need. When you’re in the public eye and you change your mind, well, that’s viewed as a sign of weakness. And then if you express doubt about something, that’s viewed as a sign of weakness today, especially in this hyper-partisan — everybody wants to be tough-minded. I don’t know. It’s like you got to shut me up. I mean, the thing I’ve most been thinking about lately, the relationship of doubt on the one hand and the life of the mind on the other, it’s really…

MS. TIPPETT: And what you’re…

MR. BLANKENHORN: It’s what you try to do in these conversations, I think.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. Well, you’re helping. We’re creating this together. What you are not saying is that this is about having a robust intellectual life, right? It’s not about not having robust thoughts and positions.

MR. BLANKENHORN: Well, it’s not about being vanilla and saying, “Oh, I agree with you and I just don’t want to say anything you would disagree with.” I mean…

MR. RAUCH: That’s never been a problem with you, David.

[laughter]

MR. BLANKENHORN: That’s never been — or you either, man.

MS. TIPPETT: OK, but everybody doesn’t know him as well as you do.

[laughter]

MR. BLANKENHORN: We called what we did achieving disagreement.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, I like that.

MR. BLANKENHORN: See, because it’s easy to have a false disagreement. I can just say, “Oh, you’re a bad person and you’re stupid. You’re some kind of religious zealot or something.” I can just have a belief. But to actually know where we disagree requires effort from you and from me. We have to have a relationship to do that. And part of achieving disagreement means identifying areas of common ground. It means finding out where we agree.

Otherwise, how do you know where you disagree if you don’t also know where you agree? And that, I’ll tell you, in today’s world of hyperpolarization and the sheer idiocy that is our public debate on most days, 98 percent of the time, the heart just cries out for this kind of serious effort to achieve disagreement.

MR. RAUCH: Could I just say there’s another element of this which was important to me, and I think is, for me, what started pushing me in your direction is when — I believe there’s an element of patriotism about this. I believe that there are higher values, ultimately, than what each of us wants as individuals.

I discovered in you, I thought, someone who understood that you’re a multivalue person and that as strongly as you felt about marriage, that you felt even more strongly that we have to share the country. And it is our duty as citizens to find ways to live together. And that that’s a higher value still. I equate that with a form of patriotism. When I see someone who won’t compromise, I see someone betraying the core purposes of our Constitution, which is to force compromise.

MR. BLANKENHORN: Right.

MR. RAUCH: That’s what James Madison was doing.

MR. BLANKENHORN: Exactly.

MR. RAUCH: And I saw in you someone who is willing to say being right about marriage is not as important to me as making a pact with my fellow Americans on the other side so that we can share this country.

MR. BLANKENHORN: We can live together, yeah.

MR. RAUCH: There’s nothing soft and squishy about that.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. BLANKENHORN: It comes across that way sometimes, but I do think — I agree. I think it’s a kind of patriotism. And you write — Jon has written for gay audiences and said things like he said, like it’s time to, like, give these religious people a bit of a break and not press our advantage. It’s time — I’m not trying to put words in his mouth, but he says this. He says sometimes a sweeping court decision to impose gay marriage is maybe not the best way to achieve the goal. I can only imagine the criticism that comes your way from your own community about that, but I think on our best days we both sometimes try for that a little bit.

MS. TIPPETT: This matter or this idea of compromise came up in this discussion that I had at Brookings with Alice Rivlin and Pete Domenici, which was a very different kind of discussion. But — and I felt later that I hadn’t followed it up enough because the notion that compromise is built into successful politics. But how can we think about — I think you’ve just helped me do this, Jonathan. How do we think about compromise and integrity going together, right? That compromise is not a relinquishing of integrity. Maybe it’s the way doubt and integrity go together.

MR. RAUCH: I think of it as duty. I think there are higher things than being right. And I think it’s time for compromisers — by compromisers, by the way, I don’t mean people who give up on their core values and roll over and get rolled by the bitter partisans on the other side. I just mean people who at the end of the day say, “You know what? I’m not going to walk out of here with everything I wanted.” I think it’s time for us to get a little bit more uncompromising in our defense of compromise.

[laughter]

MR. RAUCH: I think this…

MS. TIPPETT: Somebody is tweeting that right now as we speak.

MR. RAUCH: I think we should understand and say this is a matter of patriotic duty to our country. And that when you see someone who’s out there saying — as for example, a Midwestern senate candidate did — my idea of compromise is the other guy’s going to agree with me and everyone goes “yes.” Some people in that audience should go “boo.” You are not being a patriotic American if you are betraying the founding premise of this country.

MR. BLANKENHORN: Yeah, it’s not the trend of the times.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, “The Future of Marriage.” We’re at the Humphrey School of Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota. I’m with David Blankenhorn, president of the Institute for American Values, and Jonathan Rauch, a journalist and guest scholar at the Brookings Institution.

And now I’d like to invite Larry Jacobs — if he’s ready — to the podium. He’s going to moderate questions from the audience, both in the room and online. And Larry is Director of the Center for the Study of Politics and Governance here at the Humphrey School of Public Affairs.

LARRY JACOBS: Thank you very much, Krista. We’ve got several questions here that are struggling with the religious basis for gay marriage. One question asked, “How is gay marriage consummated? Physically, men don’t fit with men and women don’t fit with women.”

MR. RAUCH: Did you say there are several questions like that?

DR. JACOBS: That’s an example.

MR. RAUCH: Well, gay marriages are consummated by gay love, by gay relationships, by gay sex, by the fact that we will be there for each other when we’re sick, by the fact that in the days when we couldn’t get married, some of my friends held their shivering, dying, wasting partners, held them to their bodies as human blankets to keep them warm enough so they wouldn’t convulse and did that for weeks on end until the end came — when the families very often would shun these people because they were gay and because they had AIDS. This is how marriage is consummated.

MS. TIPPETT: I sometimes think we should just pause, all of us, wherever we are on the issue, and just dwell on the fact that this is a very big deal, the civilizational shift to say we are reconsidering the definition of marriage and just let that sink in.

MR. RAUCH: Yeah. That’s something I had to learn when I came into this. If you’re gay and you grow up without marriage or prospect of family, it’s obvious we just want to do what they’re doing. And it’s humiliating, the idea that you have to go around to all these straight people and say, “Oh, please, Mr. Straight Person, can I get married too? Can I be like you someday?” I mean, we have a right to this. We’re entitled to this. How dare they stop it?

It took me a long time to get my mind around the notion that in the straight world, this is not an obvious thing. This is a huge shift in the way they’re thinking about marriage for 3,000 years. And I think we need to respect that. I think societies have to ingest change at a rate they can sustain. That was something I had to learn.

MR. BLANKENHORN: Yeah. Yeah.

DR. JACOBS: David, there’s interest in consequences for your shift in position. How has your change of heart affected your organization and your life’s work? Have you paid a price?

MR. BLANKENHORN: Well, we’ve lost a lot, about half of our board and about half of our funding. So there’s a process now of just having to rebuild the thing because it was just a lot of belief on the part of a lot of supporters of the organization that this was just some place they could not go. They could not support an organization whose leader had said this. So it’s a free country, and people should do with their money and their time what they want to do, so I don’t bear them any ill will.

But that’s been a pretty big consequence and not entirely unexpected. I didn’t expect it to be quite this severe, but I think it just shows what we were talking about before. Gosh, it’s just a very — particularly for, I think, Catholics, Evangelical Christians — you’re probably up to half the country now — this is a very — it’s almost an existential question. And I’m still trying to wrap my head around it. But those have been some of the consequences.

DR. JACOBS: Could you draw a general lesson from your relationship and its change over time? How do we restore useful and purposeful engagement in public dialogue?

MR. RAUCH: David will be happy to answer that question.

[laughter]

MR. BLANKENHORN: I don’t know why it is, but I think we’re just at this moment in time where the public conversation is at a particularly low level of quality — the coarseness, the ugliness, the assumption of bad faith, the triviality, the sensationalism. I really think that so many people are aware of this. And I know it sounds small-bore, but I do think that these kind of conversations where you try to dig a little bit deeper and to try to be more serious, it just in these small ways you have a little affirming flame of something positive, a kind of modeling process.

I don’t know that there’s a macro solution right now because I don’t quite know where it comes from. I don’t know where the ugliness at the macro — I can’t diagnose it, really. I don’t have a diagnosis. So all I really know is it’s terrible, it’s bad for the country, it’s bad for our souls. And the only thing I can think of is just modeling it on a small scale wherever you can a different way of talking to one another.

MS. TIPPETT: You have some really interesting things going on on your site, the Institute for American Values, and your blog. Here’s the guidance you give — bloggers and commentators. I don’t know if you wrote this, but again in the context of the small things, right? “Be rigorous, be powerful, be funny, but don’t be mean.”

MR. BLANKENHORN: [laughs] We’ve had a — it’s really interesting, we’ve had a whole discussion on civility. We call it the “Civility Discussion,” and it sounds a little, maybe, boring.

MS. TIPPETT: I know. I worry about “Civil Conversations” sounding boring too.

MR. BLANKENHORN: Yeah. I’ve been wanting us to push deeper on civility because it seems to me that there are at least three levels. One level is be nice, just be polite. Another level is to admit that there may be something you don’t know. And then a third level, and this is the hardest, try to put yourself in the other person’s shoes. Try to actually see the world empathetically the way that the other person is seeing it. Sincerely make that effort.

You can’t enforce this, by the way. The only thing you can really enforce is be nice, be polite. But what you really want is the ability to say, “It seems like there’s no possible way that I can even — what you say is too stupid for me to even respond to, but I’m going to make an effort to see it the way you’re looking at it. And that’s not a sign of me being a weak person.”

MR. RAUCH: It’s a sign of being a strong person. It’s hard, you know. I’ve been in this debate for 16 years, and you get very angry. I’ve worked very hard to try to master that, not infallibly. But this is a decision. I mean, you’re asking what to do about this, and I’m with David. I don’t know, but I do know there are choices people make. I think we have a seventh-grade class here today. You guys are, what, 12, 13, that kind of thing?

MS. TIPPETT: We’re really happy you’re here.

MR. RAUCH: So you guys, in high school, very soon now, and then even more in college, are going to start to be confronted with choices about how you’re going to conduct yourself. And you’ll be offered opportunities to write blog posts where, knowing very little about stuff, you start popping off and insulting people because that’s really easy. That doesn’t take any…

MR. BLANKENHORN: All you have to do is imitate your adults.

MR. RAUCH: Yeah, all you have to do is imitate everyone else out there. But now and then, you’ll have the opportunity to stop yourself and say, now wait a minute. Suppose I take the other person seriously. Suppose I take seriously the idea that I might be wrong. Suppose I try to inform myself and look at the world from the other person’s point of view.

That is really, really hard, but if you start doing that once or twice in high school, then you’ll do it a little more often in college. And you — it’ll inflect your life in a very different direction. And it doesn’t take much of that to make a difference, in my opinion.

MS. TIPPETT: I think we have time for one more question.

DR. JACOBS: David, this is for you, and it comes from our online audience. I’m looking for balance and particularly to hear from people opposed to gay marriage. Who should I look to for smart representation from the other side?

MR. BLANKENHORN: I think that over the past 10 or 15 years, there have been a number of books and articles, the most recent of which is a book co-authored by John Corvino and Maggie Gallagher — John Corvino being a pro same-sex marriage gay man, philosophy professor, and Maggie Gallagher being the founder of the National Organization for Marriage. They wrote a book called Debating Same-Sex Marriage. I think I would start with the Gallagher-Corvino book. Andrew Sullivan edited a book a few years ago. I think it was called Gay Marriage Pro & Con. And Jonathan, a lot of your writings have been engagements with this. So there are good things to read.

I don’t know — I think that’s the best answer I can give. Start with those, but also realize that, see, in some ways, you’re just dealing with goods and conflict. What you’re dealing with is this fundamental need on the one hand to advance the human rights of a group of people who have been denied them on a broad level. And on the other hand, you have a consideration of the historic role in marriage and the protection of children. Those two things are not always completely resolvable. They’re in tension with one another. And that argument, I think, has — which is at least my position, I still feel that there’s not quite — we never quite got there in the public debate with this. It’s been framed in this slightly different way, but…

MS. TIPPETT: So, Jonathan, do you — I know that you probably would have said previously that David Blankenhorn was the most intelligent person making a case against gay marriage. I mean…

MR. RAUCH: The best thing, to this day, is still his 2007 book — is it 2007 — which is…

MS. TIPPETT: The Future of Marriage.

MR. BLANKENHORN: Future of Marriage.

MR. RAUCH: …Future of Marriage is still the best anti-gay marriage argument…

MR. BLANKENHORN: He’s just saying that because it’s got a good preface.

[laughter]

MS. TIPPETT: That’s right. Well, so I think this is a messy and difficult and important place to end. And that’s fitting.

MR. BLANKENHORN: Sort of how it ought to be.

MS. TIPPETT: Because this is a messy and difficult and important subject. I’m really aware — even when these numbers come out — there’s — I recently saw the Pew saying two-thirds of Democrats are now — now support gay marriage. That means one-third of them of Democrats don’t support gay marriage. So we are not on the same page on this subject. And at the same time, this anguish that you’ve both described of people watching how we navigate territory like this — that anguish I feel in myself. It was the impetus behind this series. I bet everyone out here feels it. Part of the idea behind this — and I want to thank you for so rising to the occasion — is that if we can talk about this in a way that has integrity and kindness and depth, we should be able to figure out how to talk about a lot of other things too. So I want to thank Jonathan Rauch and David Blankenhorn and everybody who was with us online and all of you for coming. Thank you.

[applause]

MS. TIPPETT: David Blankenhorn is founder and president of the Institute for American Values. His books include The Future of Marriage.

Jonathan Rauch is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, and a contributing editor to The Atlantic and National Journal. He’s author of Gay Marriage: Why It Is Good for Gays, Good for Straights, and Good for America.

Together, in 2015, Jonathan Rauch and David Blankenhorn have launched a joint initiative, The Marriage Opportunity Council, crossing liberal and conservative, gay and straight boundaries.

Listen to this show, share it with others and watch my entire public discussion with Jonathan Rauch and David Blankenhorn at onbeing.org. You can also stream this show on your phone through our iPhone and Android apps or on our fabulous new tablet app.

[music: “Take a Look” by Floratone]

MS. TIPPETT: On Being is Trent Gilliss, Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mariah Helgeson, Nicki Oster, Michelle Keeley, and Selena Carlson.

Special thanks this week to Larry Jacobs, Kate Cimino, and their colleagues at the Center for the Study of Politics and Governance at the University of Minnesota’s Humphrey School of Public Affairs.

[music: “Niedrige Decken” by Burnt Friedman & Jaki Liebezeit]

MS. TIPPETT: Our major funding partners are: the Ford Foundation, working with visionaries on the frontlines of social change worldwide at Fordfoundation.org.

The Fetzer Institute, fostering awareness of the power of love and forgiveness to transform our world. Find them at Fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, contributing to organizations that weave reverence, reciprocity, and resilience into the fabric of modern life.

And the Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

Our corporate sponsor is Mutual of America. Since 1945, Americans have turned to Mutual of America to help plan for their retirement and meet their long-term financial objectives. Mutual of America is committed to providing quality products and services to help you build and preserve assets for a financially secure future.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

![Cover of All Is Wild, All Is Silent: Remixes [Vinyl]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/41KjwMMx8HL.jpg)