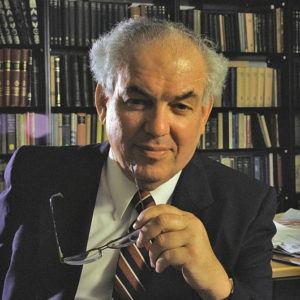

David Hartman

Hope in a Hopeless God

David Hartman died a year ago this week. The Orthodox rabbi was a charismatic and challenging figure in Israeli society, called a “public philosopher for the Jewish people” and a “champion of adaptive Judaism.” We remember his window into the unfolding of his tradition in the modern world — Judaism as a lens on the human condition.

Image by Menahem Kahana/Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

David Hartman was an Orthodox rabbi and founder of the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem. He authored many books, including A Heart of Many Rooms and The God Who Hates Lies.

Transcript

February 6, 2014

RABBI DAVID HARTMAN: The human condition is caught between two poles. I’m part of the world and I’m separate from the world. But I believe philosophy becomes true when it’s anchored in the intimacy of your life. I think within the concrete. I remember my students saying to me, “Rabbi Hartman, I want you to know, but don’t get upset with me. I became an atheist.” I said, “When did you become an atheist?” He said, “Wednesday.” “Oh, boy, that’s a remarkable thing. What were you Tuesday? You were a believer, right? And what happened on Thursday?” I said, “Is there any difference between the way you lived when you were a believer and when you became an atheist?” And that’s the criterion for me.

[Music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: “The champion of adaptive Judaism.” That was the headline of The New York Times’ obituary for Rabbi David Hartman, who died a year ago this week. He was called a “public philosopher for the Jewish people,” He was a charismatic and unusual figure in Israeli society — an Orthodox rabbi who both loved and challenged traditional Judaism from the inside. He did this as a sacred obligation to his understanding of the core values Judaism brings into the world, for all of humanity. He became an activist for example, of the inclusion of women in orthodox ritual and practice, seeing this not as a matter of or for women but about the character of the God one worships.

I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being.

Rabbi David Hartman led a modern Orthodox synagogue in Montreal before moving with his wife and five children to Israel in the aftermath of the Six-Day War of 1967. And in Jerusalem over three decades ago, he founded the Shalom Hartman Institute, named after his father. This modern campus is built with stones from the nearby Judean Hills. It hosts secular Israeli military officers, Arab thinkers, and liberal and traditional rabbis. I interviewed Rabbi Hartman there in 2011.

MS. TIPPETT: Where I’d like to start is truly at the beginning of you. Were you raised in an Orthodox family?

RABBI HARTMAN: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: So this has been your tradition all your life?

RABBI HARTMAN: No. I’ve been — I was brought up in a very Hasidic family and I went to Orthodox schools. I was a nice religious boy [laughs] until I began to read [laughs]and that all changed [laughs].

MS. TIPPETT: What did you read that changed you?

RABBI HARTMAN: William James, John Dewey, American pragmatism. They grabbed me. Also, Peter Berger and Brown.

MS. TIPPETT: And how did those kinds of writers start to change your Jewish sensibility?

RABBI HARTMAN: No, you see, I was already moving away from conventional Orthodoxy. I wasn’t satisfied with the answers. And with William James, I met a finite God, which was a pleasure. So, well, God was limited because, if I looked at the world — I mean, he sure is not omnipotent because, if that’s what his power is, then he sure is a very weak God. So in other words, I could never build the theology ignoring the lived reality. I always, in my own crazy way, would go through, when there was a plane crash or a car crash and I’m told that there was a bride and groom on the plane and I pictured what was their conversation: Where we going to live? How many children do you think we should have? And then planning and thinking. Then snafu. It’s like laughing at human beings attempt to take life seriously. Either God has a sense of humor or he’s not there. He’s there and not there. So in some way, we have to develop new metaphors, new images, of how we think about God. It’s not enough to say Judaism is the religion of the law. We have the law, so we know what we’re supposed to do. That doesn’t work for me. Because if the law doesn’t point to a God, then what is it all about?

MS. TIPPETT: You know, much of your writing and certainly this latest book you’ve written, The God Who Hates Lies, it’s an intra-Jewish conversation that you are aspiring for, leading, provoking. And it’s provocative and critical, but from a perspective of loving and living deeply inside the tradition. I’d like for us to talk about that, but be aware of the fact that people who are listening, say, my listeners in the United States, don’t know the dynamics of this internal conversation. And also, I think when Jews are critical of each other, when this critical Israeli conversation is transmitted, that loving and living in the depths piece of it is lost. So I’m just wondering if we can kind of go inside that conversation that you’re part of.

RABBI HARTMAN: You see, I see my identity as deeply tied to a family. I’m very deeply Jewish. My mannerisms, whatever it may be, I mean, I was brought up with Jewish music, my father, the institute is called after him. He was very poor, but he celebrated the Shabbat with joy. So I have deep memories, Jewishly. So I have never had the desire to leave. I had the desire that it should be better, so my criticism grows from love. It’s like I was once told, don’t be critical as your mother-in-law who enjoys to find out things that are lacking in you [laughs], but be critical out of compassion, out of real love for what you think the people could be. And as I suffered that, because on one level I want to feel empathy, intimacy, with these people with its history, with its longing, and I know its vulnerabilities, its weaknesses, its psychological problems of wanting to be loved. They want so much to be loved and it’s not working. And they don’t know why does the world hate them. What did we do? So they used to say, “It’s Christ killers.” No, it’s not that. It’s much deeper, and on a certain level, Jews are very aggressive and powerful and intellectually, but deep down, they are very frightened.

MS. TIPPETT: You were a congregational rabbi for 16 years, is that right? Before you came to Israel in Montreal? And you wrote that you, at that time, “spoke excitedly about the religious significance of a society not only shaped by the Jewish people, or even a Jewish ethos in a general sense, but organized politically around the creative contemporary application of biblical and rabbinic categories of social justice.” Then you encountered the reality of [laughs] life, right? And the human condition?

RABBI HARTMAN: Right. Yes. Like you wake up in the morning, you hear that a family were murdered. So how do you live with that, you know? And Israelis just want the world to say we feel your pain. They’re so hungry for acknowledgement. They’re so hungry for human responses to them. See, I felt that Jews entered history now affected by the totality of life, economics, politics, medical ethics. In other words, Judaism was not going to be a religion of the synagogue or the kosher home or kosher bakeries. It was going to be the Sitz im Leben of the lived reality of people in business, in violence.

I remember the Quakers coming to see me. They wanted to know about my views of power, you know, Quakers. So I said, if you have power, you can have a moral argument. If you’re powerless, there’s no moral argument. So if we want to engage the Palestinians in a moral argument of how to live together, then we can only negotiate if we’re strong. So I have no difficulty even though I’m not a militant person. I have no difficulty of Israel being strong because I feel strength invites discussion; weakness invites manipulation.

MS. TIPPETT: I wonder if your perspective as a — or if the sensibility you bring to this as a philosopher also, I mean, because really what you’re talking about is the human condition, the difficulty of the human condition, then in the context of this difficult national and religious identity.

RABBI HARTMAN: Well, that’s the — the human condition is caught between two poles. I’m part of the world and I’m separate from the world. I’m a member of a family that is not typical of the world and yet I want to embrace all of humanity because, to me, the idea of God creates the widest range of empathy for human beings. Beloved is man created in the image of God. Now on that level — but I believe philosophy becomes true when it’s anchored in the intimacy of your life. I think within the concrete. That’s what James and Dewey did for me. What’s the cash value of an idea? I remember my students saying to me, “Rabbi Hartman, I want you to know, but don’t get upset with me. I became an atheist.” I said, “When did you become an atheist?” He said, “Wednesday.” “Oh, boy, that’s a remarkable thing. What were you Tuesday? You were a believer, right? And what happened on Thursday?” I said, “Is there any difference between the way you lived when you were a believer and when you became an atheist?” And that’s the criterion for me.

[Music: “Foreign Legion” by Tin Hat Trio]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today – my interview with the late American-Israeli philosopher and Rabbi David Hartman.

MS. TIPPETT: Your daughter, um …

RABBI HARTMAN: Tova.

MS. TIPPETT: Tova is part of what some people call the Orthodox feminist revolution. Some language you used about that, about how your thinking changed towards this, towards thinking about women and Judaism, you said, was when you realized she was “not merely fighting for women’s rights, but for an honest, authentic Judaism” — that this was not about women, but about the type of God you could worship.

RABBI HARTMAN: Correct. In other words, Tova once said to me, “Abba, the problem with women in Judaism is not a woman’s problem. It’s your problem. It’s the Judaism that you want to be committed to.” Now do you want to be committed to a Judaism in which the woman is not a person? She could be a great surgeon during the week in Hadassah, she comes to the shul, she’s not part of the minyan, she’s not part of the quorum. I remember a rabbi calling me, says, “David, what should I do? I come to the shul in the morning and some people have to say Kaddish, which requires a quorum of 10 men. I only get nine and I get seven women.” When Orthodoxy denies the personhood, it commits spiritual suicide. It is blind to the human condition, to the dignity of human beings. I can’t see a Judaism that flourishes and consider the woman in a second-rate, very limited legal powers, etc.

MS. TIPPETT: And this is a discussion you’re having within Orthodox Judaism in Israel?

RABBI HARTMAN: Correct. That’s the family. Once I became aware of the depth — and I’m grateful to Tova for educating me because she’s a real expert in gender studies — once it hit me, I couldn’t accept all the apologetics.

MS. TIPPETT: And, of course, this is not just a Jewish phenomenon.

RABBI HARTMAN: I know.

MS. TIPPETT: We have — this is — there are aspects of Christianity, of all the traditions that have this. You know this tradition. You know it in its depths, you know its texts and its teachings. I mean, does Orthodox Judaism have the capacity to make this transition as a tradition?

RABBI HARTMAN: Yes. One of the things, I wrote a chapter in my book A Heart of Many Rooms, “Judaism as an Interpretive Tradition.” Interpretation is not just for sake of the law. It’s to define the reality of the religious world. Who is God?

MS. TIPPETT: Who God is, right.

RABBI HARTMAN: Whose God? Depends on how you interpret it. And I want to bring God back into the interpretive tradition because people will say. “Hartman is talking about God so much. What happened to him? What’s this God-intoxicated stuff?” They’ll get scared. So what I’m saying is I want to have God in all aspects of reality and to have that consciousness that you’re living in the presence of God should define your moral action. In other words, I don’t need legalisms to bring about changes.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

RABBI HARTMAN: You got that? I don’t need these legal shenanigans. I want to bring the person in existential confrontation with the God consciousness.

MS. TIPPETT: And then I think you’re saying that the legalisms then must be reconstructed, reinterpreted.

RABBI HARTMAN: Correct.

MS. TIPPETT: In accordance with that rather than the other way around.

RABBI HARTMAN: That’s correct.

MS. TIPPETT: Rather than that we interpret God by way of the legalisms. I’m a mother too; I have two children. And I love it that it’s your daughter who brought this to you. I’ve heard other stories of this across the years, Christian and Jewish stories, children who force their parents to revisit the teachings. I just wondered if — I thought you might have an answer to this. Does the tradition have teachings about how we should be open to being changed and taught by our children?

RABBI HARTMAN: Well, it’s either point. The tradition has models of people changing their mind. The tradition has models of the vitality of disagreements, that one point of view is not the truth. And the notion of philosophy is not truth, but possibilities. Philosophy opens up windows. It doesn’t give you final truths. I want to have a Judaism that opens up windows. You could breath. You want to convert to Judaism? Try it, try it. See how it fits you. Walk around in the streets and say, “I’m Jewish.” See how you feel about it. In other words, I have a great respect for experimentation, to learning from experience. And what experience could give you, no major work of philosophy can give you. I want the human being to be touched by another human being.

MS. TIPPETT: So as I conduct my life of conversation and as I look at the world, I feel that the teachings about the other, how to encounter the other, how to engage the other, how to treat the other, should be — should be — a great gift to the 21st century, that the world needs to learn in a whole new way how to live with the other. It seems to me that you’ve really engaged with that teaching of the other in Judaism. Does that even float into your thinking about women and your changing idea about women? And I wonder how you think about that teaching of the other in terms of the Palestinian people and that this life in Jerusalem and in Israel in the Middle East. It’s hard.

RABBI HARTMAN: That’s so painful. I remember NBC came to see me. They say, “We heard that you’ve changed in your attitude towards the Palestinians, you know, that you’ve become now militant.” It was Tom Brokaw who came to see me. I said, “Depends what time of day. In the morning I hate the Palestinians. Four hours later I’m much calmer. I don’t want to hurt them. I want to live with them. In other words, I am constantly moved up and back. When my family gets killed and my family’s frightened to go to sleep at night, I get angry. I have a lot of anger in me, but part of my tradition is to learn how to control that anger. And I don’t know if they really want to live with me. I’m not certain that there’s anything we can do that would make it possible for them to feel we acknowledge their dignity.

MS. TIPPETT: There are other sides of this, right? I mean we were last night at a dinner with Yosi Klein Halevi your colleague. Some American, young Journalism students from California, they had just spent part of the day in East Jerusalem and they were just observing the contrast between the economic dignity of Palestinian neighborhoods and Israeli neighborhoods. This is another side of this, what I would like to get a better sense of, there is this dynamic of a threat, right? And then there is the question of how you apply the teachings of the other to just basic treatment of Palestinians, even citizens of Israel. Right? Is that whole dynamic.

RABBI HARTMAN: I pray for the well being of Palestinians. I have no joy at all if a Palestinian suffers That’s not where I am. But I say to them please, we could really build a nice society together. Can’t you try? Why do you have to feel that there is a, we’re trying to Jew you, as they say? Why can’t you trust us for a little while? A little while, 20 years. I mean we could flourish together beautifully. It could be an example to the world about living with the other, really living.

MS. TIPPETT: Right

RABBI HARTMAN: I can’t fool myself. I have no other place to go. I’ve lost too many people. German Jews who trusted, you know, and I saw what happened. So I don’t trust the world. I want to trust the world. I say Hartman, come on get it straight. It depends on what time of the day you ask me. It’s living with this tremendous tense emotions. Love hate ambivalence is a phenomenon.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. I want to talk about another — you know, just to shift gears — another interesting thing that you’re bringing about that I’ve heard about: senior military officers who are coming here for study and bringing real-world ethical spiritual questions, and then you’re meeting that with the tradition.

RABBI HARTMAN: I love that. I love them.

MS. TIPPETT: I think, for people outside Israel, what would be surprising is how unusual and groundbreaking that is, right?

RABBI HARTMAN: Beg your pardon?

MS. TIPPETT: I think, for people outside Israel who don’t know the dynamics here, that it might be surprising that that’s groundbreaking.

RABBI HARTMAN: No, I think this is, for me, my most beautiful experience in Israel. I look at them and I say, “You know, you’re the true rabbis in Israel because you are affecting all your troops.” They woke up that Israelism and nationalism ain’t enough. That can’t satisfy the soul of a people and the soldiers themselves say we have to know why we’re fighting. What is it about? Why are we connected to this land? How do we connect ourselves to Jewish history? And they are marvelous. The best audience in the world. I mean, I love them.

MS. TIPPETT: What kinds of questions do they bring?

RABBI HARTMAN: What?

MS. TIPPETT: What kinds of questions do they bring? What do they want to talk about?

RABBI HARTMAN: They want to know do you accept me as a Jew even though I’m not observant? How do you look upon me? I say, “You’re not secular.” “But everyone tells me I’m secular.” I say, “You can’t be secular because you’re willing to die for the continuity of Jewish history. That’s very deeply religious.” So immediately, there’s a certain sense that, OK, I’m inside. I’m not an outsider. Take me on a trip. Tell me about Abraham. Tell me about Moses. Tell me about Maimonides. Come on, let’s walk together and I’m open to any questions you may have.

I mean they’ll ask me. Why is it my Russian friend who was here and he got killed, and they didn’t know if they could bury him in a Jewish cemetery. So the question they all ask themselves if they’re willing to accept him to die for this country, they can’t bury him as a Jew. There is such a disharmony a fracture between the rabbinic establishment or the so called public voices of Judaism and what really is true Judaism. And they’re looking for true Judaism. Something they can love and respect. It is very beautiful to see. They want to respect it. It is not like my congregation in Montreal when I was a Rabbi. I mean here it’s the nicest audience I could speak to because they are so hungry. That’s what kills me. I know the country is open to a renaissance of spiritual moral values and the Rabbis kill it. We have a Rabbi in it that has absolutely no connection to the people, no understanding of Jewish history, no understanding of the Zionist revolution.

MS. TIPPETT: You have written about, and I think this absolutely comes through, that you criticize Israel as a parent, or Jews as a parent — engages with the child. It’s a loving criticism. And you have written that the backdrop to that is daily joy and celebration. Would you say some more about the totality of this relationship you have. Your ideas, what you find lacking, your sense of possibility?

RABBI HARTMAN: Well I find lacking joy, depth, critical reflection, changing your mind and not being scared to think new thoughts. That’s what I’d like to see and it ain’t there.

MS. TIPPETT: You wrote, “I propose that a core meaning of the state of Israel is precisely the will of the Jewish people to remain in history despite overwhelming evidence of the risks involved.” Tell me what you’re saying there?

RABBI HARTMAN: Well you know the risks.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, I know the risks. It’s the staying in history.

RABBI HARTMAN: The staying here. We’re vulnerable to Syria, Iran, Hezbollah. I mean they don’t send me love notes. They tell me that they are going to get new forms of destruction and they could wipe out Tel Aviv in a few hours. I look at this institute I worked so hard to build it, I had to raise all the money myself. My son Donniel now came and inherited the throne. But i worked very hard to build what I built. I don’t want to lose it. I always have these nightmares of bombs falling away here. It’s just, I don’t know, the fragile quality of life drives me crazy. Today you’re here, today you smile, today you make love and tomorrow you don’t know what’s going to be. You know that non-consistency. And a new king arose in Egypt who didn’t know Joseph. That’s my vision of history. No matter what you did, they forgot. Look what we have contributed to civilization. Yeah ok, but that’s for yesterday’s news.

[Music: “G-D The Master of All” by Ehud Banai]

MS. TIPPETT: You can listen again and share this conversation with Rabbi David Hartman through our website, onbeing.org. There you can also find all the shows that came out of our 2011 production trip to Israel and the West Bank. They included Palestinian philosopher Sari Nusseibeh; Israeli journalist Yossi Klein Halevi; Mohammad Darawshe, an Arab civic leader of Israel; and voices from the Aida camp, a Palestinian refugee camp and neighborhood in Bethlehem. Together they reveal many faces of Israeli and Palestinian identity – and humanity. Again, that’s at onbeing.org.

Coming up, David Hartman on hope in “a hopeless God.”

I’m Krista Tippett. On Being continues in a moment.

[Music: “G-D The Master of All” by Ehud Banai]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today revisiting my 2011 conversation with philosopher and Rabbi, David Hartman. I interviewed him at the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem, which he founded. He died a year ago this week at the age of 81.

Rabbi Hartman was a revered if provocative figure in Israeli society. He convened rare encounters of Jews from different backgrounds — men and women — at his institute. These have included, for example, a project of religious and ethical reflection with officers of the Israeli army.

Israeli Jews, as Rabbi Hartman described it, walk a constant tightrope between vulnerability and responsibility.

MS. TIPPETT: One of the large themes in your thinking and writing is how Jewish sovereignty, how the fact of the state of Israel, in fact, challenges Judaism.

RABBI HARTMAN: Absolutely. Because it says to you, stop looking at pots and pans, if it’s dairy or meat. Take your face out of the pot and look, look at the society. The state of Israel gives me a whole range of responsibility.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

RABBI HARTMAN: And I can’t now goof off. I can’t blame the goyim. Can’t blame the Gentiles for the world as it is. It’s my world. What type of medicine do you have? What type of treatment of the aged? What type of treatment of immigrants? You are now — have power and power has to be measured by responsibility, and a sovereign state gives you the opportunity to make Judaism a total way of life that brings dignity and responsiveness to human beings. Sovereignty is an instrument for moral excellence.

MS. TIPPETT: And I think you’re also saying that the state of Israel is really a new chapter for Jews even beyond the biblical narrative.

RABBI HARTMAN: Correct.

MS. TIPPETT: Which does not have Jews in charge of their fate.

RABBI HARTMAN: Right.

MS. TIPPETT: And that in fact then you are writing a new chapter of the tradition, that that’s part of this responsibility you talked about, that may go beyond the bounds of what was possible even to think about or live into.

RABBI HARTMAN: That’s what this whole institute is about. In this institute, Arabs tell me when they come, they said they feel dignified. The workers feel dignified. No one pulls rank on another person. No thinker will ever be told that that’s heretical, you can’t say that. A total freedom of ideas, cross-cultural discussions with theologians, Muslims, Christians, philosophers, seculars. Come on, world. Come inside. We want to meet you.

In other words, strangely enough, Israel, which is so much more a family home, makes it possible to be more universal than living in Manhattan. In other words, here I meet people out of a sense of dignity. I have roots. I have a history. I can now meet your history. You’re not denying my identity. Like when Arafat said we were never there in Jerusalem. We never had anything to do with the temple. My anger was not, you know, that he was nasty. You denied my memory. And if you deny my memory, you deny my dignity. This is a return to memory. Now how do we deal with this memory? Narcissistically? Triumphantly? Arrogantly? Or we say now that I have my memory, tell me about yours.

It’s a different ballgame. I could listen now. I have a place. I could sit down and talk with you. I have no difficulty allowing another voice into my consciousness and that’s what Israel should be about. It’s not about that. I don’t want to lie to you. I love Israel not for what it is, but what it could be. I want that to be known. Israel is a possibility and I live with possibilities. I didn’t close the final chapter. The final chapter of Jewish history is still going to be written and it’s going to grow hair and it’s my task as a teacher or philosopher to make it possible for more and more people to study, to understand. If you look at the seminar I’m giving on the meaning of a chosen people, I want to deal with that honestly.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. How do you understand the core of Jewish teaching or the God you want to worship? How do you understand the message that is there about pluralism? What is the Jewish contribution to a truly pluralistic world that we live in now?

RABBI HARTMAN: The contribution is that there’s no idea which ends the discussion. If there’s an idea that closes the discussion, that’s not a fruitful thought. Dialogue is what creates possibility for more discussion. My tradition taught me, when they said Hillel and Shammai were always fighting with each other and disagreeing, and they say let’s ask God who’s right, is Hillel right or Shammai right? So God said, “Elu v’elu divrei Elohim hayim.” “These and these are the words of the living God.” I mean, you have a multiple conversation going on in yourself.

And there’s an old Midrash that says when he gave the Torah to Sinai, he gave it with multiple interpretations. There’s never been a single truth, a dogmatic truth, a single way of reading reality. We meet reality through the visions of other people and my tradition is filled with that. The whole Talmud is that.

MS. TIPPETT: Right, it’s a demonstration of that.

RABBI HARTMAN: Oh, God. I mean, to be a Jew is to say why are you right [laughs]? You’re going to have to explain it to me.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Right.

RABBI HARTMAN: And I’m going to argue with you.

[Music: “Zapjeval Sojka Ptica” by Mostar Sevdah Reunion]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today: my conversation with the late Israeli rabbi and philosopher David Hartman.

MS. TIPPETT: I want to talk to you about time, your understanding of time, which I would even say palpably feels different here in Israel.

RABBI HARTMAN: What?

MS. TIPPETT: Time. I mean, I’m just saying even being present in this land, it feels different. Now you write about this. It comes up in your writing not necessarily as an isolated subject, but even when you talk about writing a new chapter of Jewish history, you experienced that as a matter of generations, that you’re part of what will be a long process. Also this process of applying tradition to modern society as being the meaning of what modern society is continues to change. How do you think about the value of time, the meaning of time, in terms of religious change, spiritual evolution, within Judaism?

RABBI HARTMAN: There’s the famous saying in the Mishnah: “Lo alecha ham’lacha ligmor.” “It’s not upon you to finish the job, nor are you free to desist from it.” And know one thing: that the master is very, very demanding. “Hayom katzer” — the day is short, but the work is great. I mean, if you went to my school, the major question was how are you using your time?

MS. TIPPETT: Mm.

RABBI HARTMAN: What have you made of yourself in the gift that you’ve received? On one level, I hate time because it’s moving [laughs]. I say, hold it, kid. I want to live a little longer. I want to be around. I love life. I love people. I don’t know why. They’re not so nice [laughs], but I have that — when I see a little kindness of somebody, I see a tear in his eye. It opens me up.

I need people to take me out of a locked room and let me breath alternative pictures. Interesting, never thought of it that way. And if people could go through life feeling that there’s a lot that they don’t know, as James said, the whole truth has not been given to one person. It’s enough to be true to the section that you have, to be true to the situation of where you are and what your existential situation enables you to see and to see a world talking that way and listening. It would be nice, no?

MS. TIPPETT: Saying it that way, also, I think makes the task feel more manageable. Psychologically, it’s a great comfort to think about it that way.

RABBI HARTMAN: Yes, I do.

MS. TIPPETT: I wonder what comes to mind if I ask you. So you’ve started a lot of initiatives here. We’ve talked about some of them. You have a school. You’re training girls. I mean, you’re bringing women and girls into the tradition. You’re doing this spiritual teaching with military officers. You’re also bringing Jews and rabbis of different Jewish traditions together in a way that’s unprecedented, right? So I wonder what comes to mind if I ask you how then these experiences that you create out of your sense that something has to change, how they then give you, inform your vision, you know, teach you things that you didn’t expect to learn, give you new insights that are surprising?

RABBI HARTMAN: They tell me — they teach me that it’s not easy. You know, sometimes you can become very glib. I don’t see any dialogue in all the community. What I wanted to create was a people with discussion. On Saturday night, they get together and they say, “What did your rabbi say about Abraham? What did your rabbi say? How did he interpret this?” And they should argue what they learned, but they don’t do that. They talk, “Do you see the rabbi’s wife, how she was dressed?” So, I mean, I want a people that is learning. Where’s the spirit that awakens you? Where’s the spirit that wants you to search, find out? There’s a passage in the Psalms [speaking Hebrew], “Yismach lev m’vakshei Hashem” (“Joyful are those who seek God, not those who found God.”)

[Music: “An Ending” by Peter Broderick]

MS. TIPPETT: In terms of your own spiritual evolution, how your sense of who God is has changed, what that means …

RABBI HARTMAN: What?

MS. TIPPETT: Your sense of who God is has changed, and what that means. Are there …

RABBI HARTMAN: My God wants me to be moral.

MS. TIPPETT: Your God. [laughs] So — so I wonder if there are biblical passages or Talmudic teachings, images, that have become more important to you over time, that are important now that maybe meant nothing to you 30 years ago. What would those be?

RABBI HARTMAN: Right. Ones which are radically — radical revisions of the way you think about God. What do they mean that say God is all-powerful? His power is that he doesn’t punish the wicked. He’s slow to anger. What do you mean that he’s awe-inspiring in the temple? But there’s no temple anymore. The pagans are just dancing around in the temple. Oh, it means something else. It means if not for the awe of God, this people wouldn’t have survived in history.

So there was a reshaping of the meaning of the theological language to correspond to a hopeless God. Where are you, God? Where are you hiding? So they tell the Hasidic story of the two kids who were playing hide and seek and one kid hid and then he started crying. So they said, “What’s the matter?” Says, “No one’s looking for me.” Says, “Now you know how God feels.” [laughs] We’re not looking.

I don’t know what God is, the being of God, but I know it’s a shattering experience. It opens you to the world. It takes you out of your narcissistic ego trip and says, look, see the other. Show strength through compassion, through love, not through violence. And to be reminded each day of those achievements. It’s not easy to be a religious man. I want to be religious. I want to be religious. [laughs] But I can’t find anyone who can make me religious, who can inspire me to feel that it’s worth it. But I’m still hoping. I’m still hoping.

On my gravestone it’s going to be written: “David Hartman who wanted to be a good Jew.” He wanted to.

[Music: “March” by So Percussion]

MS. TIPPETT: Rabbi David Hartman died on February 10th, 2013 at the age of 81. He was President Emeritus of the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem, which he also founded. His books include: The God Who Hates Lies: Confronting & Rethinking Jewish Tradition.

To listen again and share this show or to watch my entire conversation in Jerusalem with Rabbi David Hartman go to our website onbeing.org. And, as we prepared to put this show back on the air, we called up his daughter Tova.

DR. TOVA HARTMAN: I miss him.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. HARTMAN: The day before he died.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

DR. HARTMAN: I sat with him and I was still arguing with him about one Talmudic passage. And literally he wasn’t — and I said, “Abba, do you agree that I was right about the place of Rabbi Akiva?” This one rabbi in the tradition in a certain Talmudic text. And people around me were saying, “Tova give up already.” But till the day before he died we were still — I was still trying to discuss certain things with him.

MS. TIPPETT: Hear the rest of my conversation with Tova Hartman at onbeing.org. And follow everything we do through our weekly email newsletter. Just click the newsletter link on any page at onbeing.org.

[Music: “On Rosh Hashanah” by David Chevan with Frank London and the Afro-Semitic Experience]

MS. TIPPETT: On Being is Trent Gilliss, Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mikel Elcessor, Mariah Helgeson, Mary Sue Hannan, and Joshua Rae.

Special thanks this week to Fouad Abu-Ghosh, Yossi Klein Halevi, and Daniel Estrin.

[On Being Extra]

[Music: “Lili Marlene” by Jack Leroy Tueller]

MS. TIPPETT: My conversation a few months ago with Buddhist teachers Sharon Salzberg and Robert Thurman sparked an interesting response. That was about love of enemies, and it reminded one of our producers of the story of Jack Leroy Tueller, a decorated World War II veteran. Two weeks after D-Day, Tueller was waiting with his troop in the Normandy countryside and he decided to take out his trumpet.

JACK TUELLER [CLIP OF YOUTUBE VIDEO]: So I get my trumpet out and the commander said, ‘Jack, don’t play tonight because there’s one sniper left.’ I thought to myself that German sniper is as scared and lonely as I am. So I thought, I’ll play his love song.

[Music: “Lili Marlene” by Jack Leroy Tueller]

MS. TIPPETT: Jack Tueller playing his trumpet today as he played it then. And hear what happened next at onbeing.org.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.