Debbie Morris, Helen Prejean, and Elie Spitz

Reflections on the Death Penalty in America

The American public supports the principle of capital punishment, but there is a growing consensus among Jewish and Christian thinkers — across traditional liberal/conservative lines — that it should be abolished in this country or suspended while the system for imposing it is made more just. Reflections on justice, forgiveness, and the nature of God shed new light on America’s death penalty debate.

Image by NeONBRAND/Unsplash, Public Domain Dedication (CC0).

Guests

Debbie Morris is author of Forgiving the Dead Man Walking.

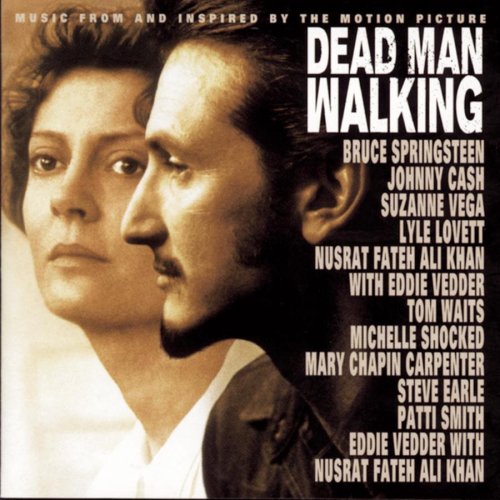

Sister Helen Prejean is a lecturer, community activist, and author of Dead Man Walking.

Elie Spitz is author, teacher of Jewish Law at the University of Judaism, and rabbi of Congregation B'nai Israel.

Transcript

April 14, 2005

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: Supporters of the death penalty cite values of justice and fairness. Those opposed say it is wrong ever to take a life. Religious language is invoked on both sides. This is Speaking of Faith, conversation about belief, meaning, ethics and ideas. Today, religious ideas and questions about one of America’s most controversial public policies of life and death, the death penalty.

CHRISTY HOLLOWELL: There’s always two sides to a story, and each, I guess, believes what they’re saying. But the fact of the matter is is that Ronnie killed my uncle. The death penalty is, is the only thing that I have. There has to be some sort of closure, and to me that’s the only closure there can be. That’s it.

MS. TIPPETT: There are ongoing constitutional challenges to the death penalty in several states, and the Supreme Court recently banned the execution of juveniles. But Connecticut is preparing to execute a murderer for the first time in four decades, and a majority of Americans continue to favor the death penalty in principle. By contrast, in recent years there’s been a striking convergence of Christian, Jewish and other religious groups, both conservative and liberal. Many are calling for an end to the death penalty or a moratorium until its application can be made more just. With the exception of the Southern Baptist Convention, the other largest Protestant denominations and the Roman Catholic Church are part of this movement. In this hour, we’ll take a look at what they consider to be ethically and spiritually at stake. We won’t indulge in simple categories of “for” or “against.” Instead we’ll consult a rabbi on the context of the Bible’s command to take `an eye for an eye.’ We’ll ask how a deeper look at ideas such as forgiveness and justice might enlarge our public deliberation.

Later in this hour, I’ll speak with Sister Helen Prejean, the author of the acclaimed book, Dead Man Walking, in which she described her experiences as a spiritual adviser to several men on death row. But we begin with Debbie Morris. The death penalty is often brought to public attention through horrific stories such as hers. When she was 16 years old, a young man named Robert Lee Willie abducted her and her boyfriend, Mark, raping her over a period of two days and shooting and torturing Mark. She later led police to the remote area where Robert Willie had buried the body of another young woman. And for that crime he was convicted and sent to death row at Angola Prison in Louisiana. But in the beginning, Debbie Morris despaired that she would ever see Robert Lee Willie brought to justice.

DEBBIE MORRIS: In my search for peace, I was looking for any way that I could to make things like they were before and the most obvious was the legal system.

MS. TIPPETT: Debbie Morris was furious when Sister Helen Prejean’s book Dead Man Walking became a best-seller and a movie because it was based in part on a compassionate portrayal of her abductor, Robert Lee Willie. By the time he was 21, Robert Willie had been in and out of prison dozens of times. Two decades after that experience, Debbie Morris wrote her own memoir entitled Forgiving the Dead Man Walking, but she did not rush to forgiveness. First, her story illuminates the impulse behind the existence of the death penalty, the very human desire of victims and their families to seek survival and healing in retribution.

MS. MORRIS: In the midst of the two days that I spent with these two men, you know, while we were in the middle of the abduction and the rapes, what I felt was just rage and helplessness, I think. I hated these two men, and I hated them for a long time. It took a long time for me to begin to consider something like forgiveness. You know, forgiveness is not our human nature. It’s not our instinct.

MS. TIPPETT: And what about the instincts of your family members?

MS. MORRIS: Oh, I mean, take what I was feeling and multiply it by, like, 100 or 1,000 for my dad.

MS. TIPPETT: So when Robert Willie was sentenced to death, did you believe at that point that that would help you find the peace that you were seeking?

MS. MORRIS: I was conflicted about it from the beginning. My emotions said that I would prefer this man be dead. He had escaped from the local jail in the past when he was incarcerated there, and I was fearful that he would escape from jail again. And he had made really awful, awful graphic violent threats against me. And, you know, there was a long time, the whole time that he was alive, that the last thing I would think before I would fall asleep at night, the last thing I can ever remember thinking is `Please, God, don’t let him come into my room. Don’t let me wake up and find him standing over me. Please.’

MS. TIPPETT: You know, I think when I read your book and hear you talking about it, your fear is so understandable and so compelling that it almost puts all those arguments for or against the morality of putting this man to death to one side.

MS. MORRIS: And that’s one of the things. When I choose to talk about the death penalty, which is not primarily what I choose to talk about when I talk about my experience, I try to convey to people who are staunchly opposed to the death penalty that there is a huge portion of people out there that when they want the death penalty and when they seem so adamant, you know, about it, and it’s perceived as being revenge, that many times it’s not. It’s fear. That’s what it was for me. It was fear. I don’t exactly remember when the hate and the revenge stopped.

MS. TIPPETT: Was that while Robert Willie was still alive you were able to stop hating him?

MS. MORRIS: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: Were you able ever to stop fearing him while he was still alive?

MS. MORRIS: No. I never stopped fearing him.

MS. TIPPETT: But you did still have these conflicted feelings about whether he should be put to death?

MS. MORRIS: The conflict really began when a date of execution was actually set for him. This was something that I thought would never happen. And it’s one thing to stand back and talk about it; it’s quite different when that date is actually set and you know that on this date, on December 28th, 1984, this person is going to cease to be alive.

MS. TIPPETT: And I believe that that day on which he died was a turning point for you, and I wonder if you would just take me through what you experienced on that day and that night on which Robert Willie died.

MS. MORRIS: It’s taken a while even for me to totally understand that. All of a sudden something was going to happen, or at least we all thought that that’s probably what was going to happen. You never know sometimes, you know. There can, in…

MS. TIPPETT: That there could have been an appeal.

MS. MORRIS: …the final hour, right, there could have been a stay of execution. But in the weeks, the days leading up to it, I just began to feel a huge burden, a huge amount of anxiety. And people would come up to me and say, you know, `Aren’t you so glad?’ You know, `Boy, that’s going to be a day to celebrate.’ And I just would sort of nod and say, `Yeah, I,’ you know, `I guess.’ And I kept wondering `What is wrong with me?’ you know, `What is wrong? I should…

MS. TIPPETT: That you couldn’t celebrate?

MS. MORRIS: Yes. I should be grateful. And I realized on the night of the execution that a big part of it was that I was beginning to panic and become desperate that when this man finally paid the greatest price that he could pay here on earth, his life, that I was going to wake up the next morning and still not be better. Then what is there left for me?

MS. TIPPETT: Where did that take you then, that new thought?

MS. MORRIS: That took me back to a distant memory and a distant feeling of what had given me the greatest sense of peace that I had ever known in my life. I had not called on the power of God to help me through this because I was too angry with God for not sparing me from the kidnapping and the rapes. And I guess it was in desperation that when all else had failed, you know, and I had been through some really tough, tough times, drinking to try to kill the pain and, you know, and holding out on my hopes that, you know, that the legal system would finally cure me. And then I realized this was sort of the end of the line.

MS. TIPPETT: Debbie Morris. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, “Reflections on the Death Penalty.” My guest, Debbie Morris, was the victim of a violent abduction and the key witness in a trial that led to her abductor’s execution. As she speaks now to groups of other survivors and families of victims, she finds that those who are able to move on and find joy in their lives are people who come to some form of forgiveness. This is a common denominator, she says, whether they oppose the death penalty or favor it. But I asked her what forgiveness looks like when the person who hurt you never showed any remorse and how did she forgive a man who had already been executed?

MS. MORRIS: I think the first thing that I had to realize about forgiveness is that I didn’t do it for Robert Lee Willie. There was nothing really noble about it. You know, for people who say, `Oh, wow!’ You know, `You’re so incredible. I can’t believe that you were able to forgive.’ It wasn’t like that. I did it actually very selfishly because I was looking to feel better myself. I didn’t do it for him. The night that I realized that I needed to forgive Robert Lee Willie, he certainly didn’t benefit. He was electrocuted to death. He never knew that I forgave him, and it wouldn’t really have done him any good to know, you know, unless in some way that motivated him to see, you know, an ultimate good in somebody and be able to, you know, to turn to God and ask for his own forgiveness. He didn’t get let off of any hook because I forgave him. Really, I guess, I let myself off the hook, and there was a sense of relief immediately that came with that. And then it doesn’t always look like immediate recovery, immediate healing. Just because you decide to forgive, it doesn’t mean it’s going to automatically happen. I mean, it’s work. You have to do it in your head first, having faith that your heart’s going to follow. And you have to do it daily. You know, you need to say, you know, `God, help me forgive this person. Help me to put this pain in the past.’

MS. TIPPETT: And still, you know, what are we talking about? When you forgive him, you no longer hate him? Are you changing the way you think about him or what he did to you? What’s changing? Just really trying to get inside this word.

MS. MORRIS: I think it means trading away the hate and being filled up with something better for me. Yeah, I definitely think that it means that I have to relinquish the hate. Does it mean that, you know, I would have lunch with him? No. I think I would have always feared Robert Lee Willie and he would not have been a safe person for me to ever see and go through that process with, for me to, you know, to openly, overtly, you know, go through the act of forgiveness with. I think that some forgiveness is not done with the other person. And, you know, I just think it would be really terrible if just because another person never said they were sorry or really was remorseful for the things they had done that we would have no way out of the hate and the pain. You know, I think God gives us a different way. He says `Forgive,’ and he doesn’t say, `Sit around and wait till this other person is really sorry. Sit around and wait till they’ve suffered long enough.’ He says `Forgive them.’ And there is immediate benefit to that. There’s not immediate total complete healing; that’s going to be a process.

MS. TIPPETT: Debbie Morris. Her story was told in part in the 1995 movie “Dead Mean Walking.” She spent two harrowing days as a captive of Robert Lee Willie. Even in the midst of that, she experienced him as a damaged and underdeveloped human being. Robert Willie was executed at the age of 26. Studies have documented that a high percentage of death row convicts suffer from untreated mental and emotional disabilities stemming often from childhood poverty, abuse and neglect. Years after her abduction, Debbie Morris began to reflect on such statistics differently. She spent several years as a teacher to children with behavioral problems.

MS. MORRIS: You know, these were the kids who had been kicked out of regular classes, and most of them had been kicked off their Little League teams, and, you know, they were about an inch away from being kicked out of the school altogether and, you know, my classroom was their last stop. And every morning, I would put my arms around them and hug them and say, you know, `Boy, am I glad you’re here today,’ you know? And I would encourage these kids and I would compliment them and do my very best to find what was good about them instead of what was wrong with them. And these are kids, you know, several of my kids were in foster homes, a couple of my kids had been physically abused, and mostly all of them lived in poverty. And one day I realized that if Robert Lee Willie had been a student in my school — you know, he had had a history of having learning problems and such — he would have been in my classroom, and he would have walked through my classroom door every day, and I would have put my arm around him, and I would have hugged him. Am I making excuses for him? No. Because of all of those students of mine that I had in those first two years, two of those little guys have been incarcerated, but there are about 15 of them that have not been. So Robert Willie had choices. So I’m not making excuses for him, but I think it’s important for us to go beyond blaming and judging and punishing and start looking for reasons why some people end up giving in to evil, why the evil prevails in their lives and they end up making the choices that they do. I am not to the point that I think that all executions, all capital punishment is necessarily wrong. I always try to look back to the Bible, you know, for my information, and I think that there are definitely places where it shows that capital punishment was condoned by God. However, we have really messed up that whole system, I think. The way that we are doing capital punishment in this country today is wrong, it’s unfair, and we have made so many mistakes. And so, you know, I can’t sit by and condone the way that we are doing executions in this country today. Do I think that it’s wrong and that the people who are involved are people who are for the death penalty, do I believe that they are out of God’s will? No, I don’t. So it’s not a completely black and white issue.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, as I’ve looked at this whole issue and the whole complex of issues around it, it feels to me like there are problems in the justice system and issues that have to do with the way that the media covers this kind of thing that may harass victims of crime and push them into a position of needing capital punishment.

MS. MORRIS: Well, sure. You know, because of the different ways the laws are written in different states and all, it’s sort of if you don’t have the death penalty, then you’re not sure that somebody’s going to even be in prison for life. That fear accompanied with the emotional reaction of what has happened to somebody for it to even be a death penalty matter, there’s been a horrible crime and there is, you know, there’s a victim that we feel we need, you know, we need to do justice for, and so the emotional aspects of that, I think, take over a lot of times. And I think that, you know, there are a lot of issues out there that because of the way the media covers them or, you know, because of the way people are asked, you know, you’re put into a category of “for” or “against.” You’re either for it or you’re against it.

And when you are on the outside looking in, it’s easy to be for or against something. But, you know, let it be your neighbor or your uncle, you know, your family member, your child. You know what? I bet that before this happened, I bet Robert Lee Willie’s mother was for the death penalty. I bet she was. We grew up in South Louisiana; Robert Lee Willie lived in a neighboring town. It was a rural area. I would venture to guess that about 98 percent of the people in the community that Robert Lee Willie was from would say in a heartbeat that they were for the death penalty. When all of a sudden it was her child, she obviously changed her mind. And I think that anybody put into that position, you know, would feel the same way. I think it’s important that we start putting human faces on these people and also remembering the other victims, the family members of the condemned people. I watched some footage where, you know, they were outside of Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola. They were filming the crowd outside at one of the executions, and there was, I believe it was the younger sister of the man who was being executed, and she was out there, outside the gates, you know, protesting against the death penalty. It was his niece. When they came out and announced his death, his time of death, this girl sobbed uncontrollably with her whole body. You know what kind of sobbing I’m talking about? Like where your whole body just trembles. And I thought to myself, `You know, we’ve just created another victim.’ This girl, this young girl — she was like maybe 14 or something — she is now going to have to go through life with that experience. And I think about the mothers, you know, of these people. And it’s easy to say, `Well, you know, you shouldn’t have raised a killer’ until it hits close to home.

MS. TIPPETT: Debbie Morris’ book is Forgiving the Dead Man Walking. This is Speaking of Faith. After a short break, Rabbi Elie Spitz on the Biblical teaching `an eye for an eye’ and what it really means; also, Sister Helen Prejean, the author of Dead Man Walking. On our website at speakingoffaith.org, you’ll find in-depth background and reading recommendations on the ideas in today’s show and information about purchasing a copy of this program. You can also listen to my extended conversation with Debbie Morris. And while you’re there, sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter which includes previews, extras, and my reflections on each week’s program. That’s speakingoffaith.org. I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us.

[Announcements]

Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, conversation about belief, meaning, ethics and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today we’re exploring religious ideas and questions about the death penalty. Recent rulings from the Supreme Court have banned the death penalty for certain classes of criminals, including juveniles and the mentally retarded. From 1967 to 1977 the court imposed a total moratorium on capital punishment because of concerns about the equity of its application. It was later reinstated in 38 states. But new constitutional challenges have been fueled by improved DNA testing which has demonstrated that innocent people have spent years on death row or have already been executed. Before leaving office in 2003, Republican Governor George Ryan commuted the sentences of Illinois’ death row convicts. As with many moral issues that reach the arena of public policy in this country, Christian voices have largely defined the values at stake. The Catholic Church has come to condemn capital punishment as part of its consistent ethic of life, affirming the sanctity of life from conception to death. But when it comes to capital punishment, Americans who favor it are just as likely to look to scripture and tradition to affirm their opposing view.

PAT WINKLER: Considering what all he’s done and the way our family has suffered over it, I don’t think it would be wrong to wish him dead. You know, the Bible says `eye for an eye.’

MS. TIPPETT: Pat Winkler’s brother was murdered and her brother’s killer was ultimately put to death by lethal injection in North Carolina.

MS. WINKLER: I mean, I am a Christian, I believe in God and I go to church all the time. In fact, this thing was bothering me so I talked to my Sunday School teacher today to see if I was totally wrong to wish somebody dead. But she said, no, said it was not wrong in a case like this. But I think I’ve made my peace. I think it will ease the pain. You know, it’ll just all be over. It’ll just all be probably like a bad dream.

MS. TIPPETT: In national polling, a large percentage of Americans, like Pat Winkler, cite `an eye for an eye’ as a rationale for the death penalty, but what does that phrase really mean in its Biblical context? My next guest, Rabbi Elie Spitz, is a child of Holocaust survivors, and so, he says, he knows about the reality of evil which cannot go unpunished. He had an early career as a criminal lawyer. He’s written widely on the intersection of faith and ethics, including the death penalty. I asked Rabbi Spitz to take us inside the `eye for an eye’ command. He first of all points out that in the ancient world, as in much of human history, there were no prisons and no civil system of justice as we know it. It was up to family members to avenge crimes against their loved ones.

ELIE SPITZ: That Biblical line…

[Speaking Hebrew]

…`an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth,’ appears twice in the five books of Moses in both Leviticus and in Exodus and is an example of how you can’t understand the Torah, the Bible literally, that even that line which seems so straightforward requires, as the rabbis understood it, requires interpretation. It’s about equity. That line is about fairness.

MS. TIPPETT: The `eye for an eye’ passage arose not to impose harsh punishment but to limit revenge, as in `You may not slaughter the entire family of the person who did this to you; you may only take an eye for an eye.’ But even that, the rabbi said, may not always pass the test of fairness.

RABBI SPITZ: They said, you know, `Imagine if a thief had only one eye and put out an eye of a person?’ Well, in that case, the punishment would not be equal because the thief would have blindness.

MS. TIPPETT: The thief would be blind. Uh-huh.

RABBI SPITZ: And therefore you can’t always have justice with an equal act. Rather, it is best and fairer and more human to engage in monetary compensation.

MS. TIPPETT: Still, the life of a human being, created in the image of God, is said to be of infinite value, and like many Jews and Christians, Rabbi Spitz insists that the Bible does give civil authorities the right, even the mandate, to legalize capital punishment. But when Elie Spitz looks back at rabbinic wisdom on this subject, he finds an ancient caution that in order to be moral, capital punishment must be meticulously administered. Under the rabbinic law encoded in the Talmud, two eyewitnesses were required to condemn a criminal to death.

RABBI SPITZ: Because God throughout scripture is concerned about this balance within creation, this balance of justice and balance of fairness. And the taking of a life for a life, capital punishment, in some cases, is even more just than keeping a person in prison. But having said that, God also wants the system to be administered justly because it’s even more egregious the taking of a life wrongfully by the state, and that’s my problem with the American system at the moment. It doesn’t work in practice. What I learned as a lawyer, back to the personal issue, is that rarely is evidence unequivocal.

MS. TIPPETT: So back to the rabbi’s wisdom that you have to have two eyewitnesses or it doesn’t count. I wonder if we could talk about the specific crime of murder and also note that in the Bible, initially, capital punishment in different forms was prescribed for all sorts of crimes, right? Not just murder.

RABBI SPITZ: Oh, yes. Though again, and now I say it a little defensively as somebody who holds the Bible dear and a sacred text, all of those claims like the Bible saying that a rebellious child should be brought to the gates and stoned, the Talmud would say, at least according to a majority opinion, this never occurred nor never would occur. It’s simply a warning underscoring the importance of respecting parents. So that sometimes it’s there more to emphasize the negative nature of behavior rather than to describe, as a code, the punishment.

MS. TIPPETT: It’s very striking to me that the first murder is that of Abel by his brother, Cain, and that his life is preserved and protected by God, and he goes on to build the first city.

RABBI SPITZ: Right. The first murder of the Bible goes unpunished by capital punishment. And I think what it does underscore is the gap between an ideal, the ideal of life for life and the messiness of determining how clear-cut and how cold-blooded an act was that would justify the ideal. And, two, underscores God’s own ambivalence in administering justice strictly.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. This is a saying of the Talmud, I believe, this haunting saying, `Every one that kills one life, it’s as though he or she had destroyed an entire world.’

RABBI SPITZ: That’s right. It’s the charge, interestingly, to witnesses in a capital crime. So when they’re getting ready to testify, the caution is `Wait a minute. Know that you’re going to be talking and testifying about why somebody should be put to death. If you put somebody to death, that’s like destroying a world.’ And the flipside, saving a life is like saving an entire world.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, for me that saying is so weighty. It’s not something that you could put into a civil law, but if that’s part of your context for thinking about a civil law or civil process, it would change it.

RABBI SPITZ: Absolutely. There’s a man who taught law at Yale for many years, Robert Cover. He wrote a very important essay, Yale Law Review, called “Nomos and Narrative,” and what he basically said is that laws, as written, can only be understood by the narrative behind them in which they’re embedded. And so when you have a law like the taking of a life for a life, clearly the narrative behind it is every life is a world, and you could only administer the law in light of the narrative.

MS. TIPPETT: You have written about the survival of the soul, which is an unusual topic to take on within Judaism. Judaism has not been so concerned with the afterlife. And I wonder if you’ve thought about if death is not the end and if, as I think is implied in all of our traditions, life and death are great mysteries, what does that say about the morality, the efficacy, you know, the meaning of the death penalty?

RABBI SPITZ: Well, interestingly the rabbis of the Talmud say that death itself is atonement at times. So they use the example of King David and his act of setting up Bathsheba’s husband, Uriah, for death and his adultery.

MS. TIPPETT: That’s one of the great figures of Judaism.

RABBI SPITZ: Correct. And they basically say he was never forgiven in this life for those felonies; it was only when he died that he was fully forgiven. That’s not a statement about capital punishment for me as much as it is a statement that when a person dies, even people put in prison for a lifetime, their death is some atonement. I can’t always say full atonement. And I think back to Hitler. I’m often asked because of this book I wrote, Does the Soul Survive? do I believe that Hitler is forgiven? And I tend to say, `I hope not’ simply because of the egregiousness of his inhumanity. But again, there is a sense that people are cleansed somewhat by death itself. The Bible says…(Hebrew spoken)…`Justice, justice you shall pursue.’ And the rabbis ask two questions: Why is the word `justice’ repeated twice, and why is it `pursued’ rather than `obtain’? And it says it’s repeated twice because means and ends must each be just, meaning the system must be just as well as the outcome. And it’s pursued because the nature of justice is it’s always a little elusive. You pursue it, you never fully obtain it. I’m grateful for this kind of conversation because that word…(Hebrew spoken)…`and you shall pursue,’ calls on all people to actively, consciously engage in examining what is a fair system and a fair outcome? What is justice? And fundamentally to keep the big picture in mind, that’s the challenge of a religious perspective.

MS. TIPPETT: Elie Spitz is rabbi of Congregation B’nai Israel in Tustin, California. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, “Reflections on the Death Penalty.”

The Southern Baptist Convention is the only major Christian denomination that at present actively endorses the policy of capital punishment. Still, the official Southern Baptist position echoes Rabbi Spitz’s perspective in significant ways. It calls for capital punishment to be applied as justly and fairly as possible, administered only when there is clear and overwhelming evidence of guilt. The Southern Baptist Convention’s resolution includes these words: “All people, including those guilty of capital crimes, are created in the image of God and should be treated with dignity.”

Here’s the voice of Ronald Frye speaking from death row in North Carolina. He fatally stabbed his landlord in 1993.

RONALD FRYE: Eight years, November 17th, that I’ve been on death row. There’s no contact visit here until, unless you have that execution date. Then you can have that one contact visit that day, the day before the execution. I’ve been wanting to get my brother in a bear hug. I told him I’d get him in a bear hug and I’m not going to let him go, you know? But it’s going to be nice. You know, it’ll be nice to be able to hold him. It bothers me to be away from my family. But, I mean, you know, this isn’t the final journey, I guess you might want to say. Like I say, I don’t fear death. I’m not afraid of it. Gotta die some day. When I was young I wanted to be a fireman, but that was just a kid’s dream I guess. What would I be doing now if I wasn’t here? I have no idea.

MS. TIPPETT: Ronald Frye died by lethal injection shortly after this recording was made on August 31st, 2001.

HELEN PREJEAN: Let me tell you something. One of the great discoveries of my life has been that sometimes you find God where you least expect to find God.

MS. TIPPETT: Sister Helen Prejean was 40 years old when she was first asked to become a pen pal to a man on death row, Elmo Patrick Sonnier. She’d committed herself to working with the poor, and most of the people on death row in this country are poor. Disproportionately, they are also people of color. Sister Helen found that her experience as a spiritual adviser to Sonnier and later to others began to reshape some of her most basic religious convictions.

SISTER PREJEAN: I come onto death row. The first visit I’ll never forget. My heart was beating, my fingertips were cold, I had a cold ice band in my stomach. And this man that I’d been writing to, Patrick Sonnier, I mean, in the back of my mind I think I had the image of a monster, and here the guard brings in this man, all chained hands, legs, and he brings him into this booth, and I looked through this mesh screen. I went, `Oh, my God! He’s a human being!’ I looked into his eyes, and he was smiling. And he said, `Sister, you came. I’m so glad to see you.’ I couldn’t believe how human he was. And you, kind of like your soul’s a magnet moving. And this, I guess, is what compassion does in us, it allows us to experience goodness in people, even in people who have done unspeakable evil. There’s more to every human being than the evil they have done. Me, too, all of us. We’re more than the worst act of our lives, all of us.

MS. TIPPETT: In 1993 Sister Helen Prejean published Dead Man Walking. It became a New York Times best-seller. In the movie, Susan Sarandon played Sister Helen, and Sean Penn portrayed a murderer she accompanied to his death.

MATTHEW PONCELET (PLAYED BY MR. SEAN PENN): Dear Sister Helen, thank you for writing to me. I’m writing from my home, my six-by-eight-foot cell. I’m in here 23 hours a day. We don’t work on death row. We’re special here. They keep us away from the general population of the prison. We’re the elite because we’re going to fry.

MS. TIPPETT: “Dead Man Walking” affected moviegoers’ attitudes towards capital punishment in part because it portrayed a hardened murderer as a human being, even a human being capable of spiritual growth. And Sister Helen Prejean insists that this dynamic plays itself out in American courtrooms as well. Only 1.5 percent of capital cases end in the death sentence. Her research, and that of others, suggests that the determining factor is not the atrocity of the crime committed, it is that the poorest defendants in our society can’t afford adequate legal help. Without that, they appear as less than human before a jury. In the last two decades, Sister Helen says she has witnessed a stunning convergence of the secular human rights movement and religious values on the death penalty. She’s also seen the demise of a strict conservative/liberal divide. One turning point was the high profile 1998 execution of Karla Faye Tucker, the first woman to be put to death by the state of Texas since 1863.

SISTER PREJEAN: You know, I began to write to Pat Sonnier on death row in 1982 and then witnessed his execution in 1984. Then Robert Willie in ’84, then Willie Salstein in ’86 and then two more since. And, you know, you come to this crystal-clear understanding what makes the death penalty possible. We have to turn a switch in our soul somewhere that that person is not human the way we are. It’s what makes all forms of prejudice however — that happens there, too, `Oh, well, you know, those — and they used to say this in the Jim Crow days in the South, `Well, they don’t feel like we feel. They don’t have the same sensibilities that we feel.’ And so once you put yourself in that position as a society of saying, `Some among us are not as human as the other and we can dispose of them,’ we’re in a very dangerous moral position.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, Karla Faye Tucker is a particular person who died on death row who brought a lot of people who’d been for the death penalty for religious reason around to seeing this subject in a different way, at least in her case. And I believe that you got to know her. What was it about her? What did she do that was different?

SISTER PREJEAN: You know, Karla had that beautiful, sweet face. She had done the unspeakable crime of killing those two people under drugs. She even stole a Bible. She didn’t know they gave you a Bible in the prison, she stole one. And she began to read the Gospels and learn about Jesus. And everybody over the 14 years who’d known Karla knew that she was a transformed person, and that came through. And see what made Karla’s death different, she was on “Larry King” for like, what, two hours? She was in everybody’s living room, and you could hear this woman talk. Now on one side, they know the terrible crime. She killed two people with a pick ax while she was under the influence of drugs. They got that on one side of their souls. And here’s this woman talking about love and compassion and how sorry she was for what she’d done, but now she would spend the rest of her life trying to love other people. And how do you put those two things together? It was hard to kill Karla Faye Tucker, and even the head of the Clemency Board of Texas said, `We can’t be making exceptions because someone found Jesus.’ Transformation of a human life had nothing to do with the death penalty. They were freeze-framing Karla Faye Tucker in the worst act of her life, then they were freeze-framing themselves in having to kill her. And that’s why the death penalty is not morally good for us.

MS. TIPPETT: There’s a theological perspective that allows you to make that observation, right?

SISTER PREJEAN: Mm-hmm. Sure.

MS. TIPPETT: And it can’t be…

SISTER PREJEAN: You can find a theological…

MS. TIPPETT: …built it can’t be built into the legal system that human beings change.

SISTER PREJEAN: But you know what can be built into the legal system? The heart and nub of it all, dignity for the human person. How can you say you’re upholding the dignity of a person when you’re torturing and executing them. There’s no way there’s any dignity in that. And that’s a universal declaration of human rights of the United Nations. Article Three, every human being has a right to life. Article Five, no human being shall be subjected to degrading punishment or torture. That our law can begin to embody, and that’s what we must work for. I think that the death penalty position is a litmus test of the image people have of God. And there are a number of us out there that really do believe in this vengeful, `eye for an eye,’ pound-of-flesh, a death-for-death God.

MS. TIPPETT: But this is so hard because your God of compassion is also going to forgive them, right?

SISTER PREJEAN: That’s right. Doesn’t mean there won’t be an honest conversation in there before that happens. And you know what? I used to have that same image of God. I used to have an image of God that was fearful. It was like, `You do good and God’s going to reward you in heaven. That’s going to be real great.’ Then the punishment was so fierce if you fell into what Catholics call a mortal sin, a grievous sin, I was scared to death of God. I started out that way. I understand that, but that isn’t the God I believe in now. Now I believe as love grows in us and truth grows in us, I think our God grows, too.

MS. TIPPETT: Sister Helen Prejean is a member of the Order of St. Joseph of Medaille. She’s the author of Dead Man Walking: An Eyewitness Account of the Death Penalty in the United States. She’s also published a new book, The Death of the Innocents: An Eyewitness Account of Wrongful Executions. Earlier in this hour, you heard Rabbi Elie Spitz and also Debbie Morris who wrote Forgiving the Dead Man Walking. The dynamics of the death penalty debate in America are changing. The same religious traditions that endorsed capital punishment for centuries have come to question it. They do so contrary to majority public opinion. And with every high-profile crime, lofty moral and theological arguments can sound pointless. The voices in this hour honor the difficulty of virtues like forgiveness, compassion and justice, but they challenge all of us to resist an emotional rush to judgment on a public policy that engages the enormous mysteries of good and evil, life and death.

We’d love to hear your thoughts on these ideas. Please send us an e-mail through our website at speakingoffaith.org. There you’ll find in-depth background, including extended conversations and selected links to secular and religious facts and discussions about the death penalty. You’ll also find information about purchasing a copy of this program, and you can sign up for our e-mail newsletter to get my weekly reflections, previews and program extras. That’s speakingoffaith.org. Special thanks this week to 360degrees.org, a website examining multiple perspectives on the American criminal justice system. You’ll find a link to them on our website.

[Credits]

I’m Krista Tippett. Please join us again next week.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.