Diane Winston

Monsters We Love: TV's Pop Culture Theodicy

Amoral zombies. Loving vampires. Righteous serial killers. And lots of God. That’s all in the new TV season — a place where great writers and actors are telling the story of our time — playfully, violently, soulfully.

Image by Joanes Andueza/Unsplash, Public Domain Dedication (CC0).

Guest

Diane Winston holds the Knight Chair in Media and Religion at the Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. Her media and religion blog is called "the SCOOP."

Transcript

December 1, 2011

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: A zombie show — AMC’s The Walking Dead — is breaking all-time cable viewing records. It’s especially beloved by the young. And it’s about more than zombies. It’s about bodies devoid of souls, and life reduced to survival. As strange as it may sound, television is a place where some great writers and actors are asking big questions of our time. So we’ve once again called up media and religion watcher and TV aficionado Diane Winston — for a look at the current season’s in-your-face themes of God, meaning, and “re-enchanting” the world. What are all those righteous criminals, amoral zombies, and loving vampires saying to us and about us?

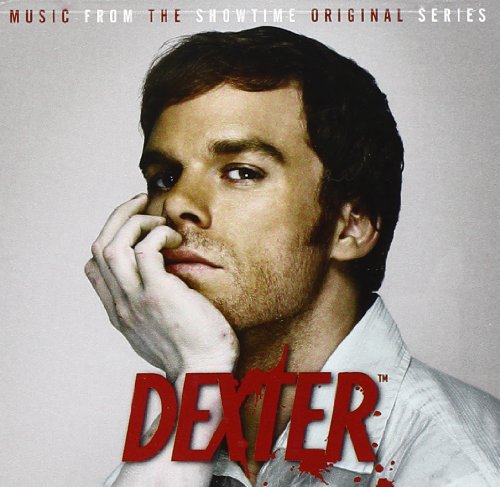

[Clip from Dexter]

BROTHER SAM (AS PLAYED BY MOS DEF): You know the good book tells us that there’s no darkness that the light can’t overcome. So all the darkness that you think you got inside you.

DEXTER MORGAN (AS PLAYED BY MICHAEL C. HALL): Yeah?

BROTHER SAM, DEXTER (AS PLAYED BY MOS DEF): All it takes is just a little bit of light to keep it at bay. Believe me. I know.

[Clip from Nurse Jackie (Season 3, Episode 5 “Rat Falls”)]

GLORIA AKALITUS (AS PLAYED BY ANNA DEAVERE SMITH):Of all the statues in here this is the one that matters the most to me. She’s tall. She’s got a lot on her mind. And I relate. Also, she’s not judgmental — that’s something I’m working on. It’s irrational but that’s the nature of faith. We’re stealing her. You were never here but since you are — strap Mary to the dolly and follow me.

[Clip from True Blood]

GOODRIC (AS PLAYED BY ALLAN HYDE): Two thousand years is enough.

ERIC NORTHMAN (AS PLAYED BY ALEXANDER SKARSGÅRD): Yeah?

GOODRIC: Our existence is insanity. We don’t belong here.

ERIC NORTHMAN: But we are here.

GODRIC: It’s not right. We’re not right.

ERIC NORTHMAN: You taught me there is no right and wrong, only survival or death.

GOODRIC: I told a lie, as it turns out.

KRISTA TIPPETT: From APM, American Public Media, I’m Krista Tippett. Today, On Being: “Monsters We Love.”

Diane Winston holds the Knight Chair in Media and Religion at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. I last interviewed her about TV and parables of our time a couple of years ago. And a lot has changed on the planet and the small screen since. Lost has ended. But its setting of human characters in a supernatural place is turned inside out now in series like True Blood, where vampires, werewolves, and witches make hay in small-town Louisiana. Meanwhile, the protagonists of shows like Dexter, Nurse Jackie, and Breaking Bad — they turn the meaning of morality inside out. And then there are the zombies.

[Clip from The Walking Dead (Season 2, Episode 7 “Pretty Much Dead Already”)]

HERSHEL GREENE (AS PLAYED BY SCOTT WILSON): There are people out there who haven’t been in their right minds. People who I believe can be restored. It doesn’t matter if you see them as human beings any more. But if you and your people are going to stay here, that’s how you’re going to have to treat them.

KRISTA TIPPETT: So let’s just say, the second-season premier of The Walking Dead, which I’m just waking up to, was the highest-rated drama telecast in the history of basic cable, and it’s really breaking records in the 18 to 49 demographic. On the AMC show page, you know, they’re telling the story and then they say this: Instead of the zombies, it is the living who truly become The Walking Dead.

DR. DIANE WINSTON: Mm-hmm. That’s interesting because a lot of shows have monsters who are monsters, but there are also monsters who are actually human beings in other shows. Who’s to say whether Dexter or Eric in True Blood is more of a monster.

KRISTA TIPPETT: And Eric is 1,000-year-old vampire and Dexter is a 21st-century guy who’s watched his mother be killed when he was a child and is a serial killer himself, although he kills bad guys.

DR. WINSTON: Right.

KRISTA TIPPETT: I mean, I do want to talk about this especially because The Walking Dead is really hitting something for people. I have to say, when we online started telling listeners that we were going to be having this conversation with you and talking about television, we immediately got all these requests to make sure we spent a lot of time with The Walking Dead. And, you know, echoing what you said, people are really talking about it being an example of pop culture theodicy, that it’s bringing out a deep sense of meaninglessness and divine absence.

DR. WINSTON: Right, right. And the zombies are a perfect representation of that because, unlike werewolves or vampires who interact with people, zombies don’t do very much. I mean, they’re wonderful symbols because you can project so much on them, but they’re not great playmates.

KRISTA TIPPETT: Yeah [laugh]. Well, and part of the theological idea is that they are bodies are detached from souls in a way.

DR. WINSTON: Right.

KRISTA TIPPETT: Not just that they’re detached from life, they’re just activated brain stems. But then you have — then you have…

DR. WINSTON: Wait, are you saying vampires have souls then?

KRISTA TIPPETT: Yeah, well, I don’t know. That’s another question we can get to [laugh]. Vampires have emotional lives. At least the vampires you and I know from True Blood have emotional lives.

DR. WINSTON: Right — which zombies don’t.

KRISTA TIPPETT: No. Vampires have relationships, good or bad.

DR. WINSTON: Right. Zombies kind of push the boundaries of what is human because, as you say, they have bodies, but they have no emotions, they have no souls. So what is our response to them and our responsibility for them? It’s a harder question.

KRISTA TIPPETT: Right.

DR. WINSTON: So you think all these people are watching The Walking Deadbecause they’re trying to figure out, you know, how do I react to a world where I feel like I’m cut off from everything and I can’t find meaning?

KRISTA TIPPETT: Well, I’m not sure that I know how to describe why people are watching it. But let’s say, for example, when you and I spoke a couple of years ago, we talked about Lost. And there’s a sense in which it’s the same kind of — there’s a similarity between, you know, setting this small group of survivors out on this, you know, constant adventure where they are confronted with horrors that have a certain supernatural bent to them and they’re surviving.

But The Walking Dead is much bleaker than Lost, right? I mean, Lost had all this pathos and beautiful moments and people finding love and redemption. The Walking Dead is a very dark view of life as a kind of — you know, there’s a line. I was watching an episode of this woman who talks about this endless, horrific nightmare we live every day.

DR. WINSTON: Mm-hmm. And there is no miraculous or wonder or redemption. Did you see the episode where one of the main characters was talking about “we need a miracle, we need a miracle” and what happens is the boy gets shot?

KRISTA TIPPETT: Yeah, so let’s set this up. This was the second-season premier, which so many people watched, where they come across a Southern Baptist Church. And they walk inside and Rick, who’s the kind of closest thing they have to a hero — well, first of all, they come inside and there are about three zombies sitting in pews looking at a huge crucifix, which is kind of interesting. You have no idea if they’re thinking or what’s going on. But then…

DR. WINSTON: No, they’re saying to themselves, “Why is there a crucifix in a Southern Baptist Church?” Right? [laugh] What happended to the production design?

KRISTA TIPPETT: I know [laugh] that is a problem with the — I know. Well, what happened with the people who didn’t really understand that it shouldn’t be a Southern Baptist Church? But it’s also a bigger crucifix than any crucifix I’ve ever seen anywhere. So they have their battle with the zombies and then, interestingly, a few of them walk in and say prayers. Here’s Rick — and this is the moment before that you’re talking about.

DR. WINSTON: Wait. The zombies say the prayers or the people say the prayers?

KRISTA TIPPETT: No, no. The people say. They get rid of the zombies, they have the zombie battle, and then a few of them walk in and say prayers that feel like this is the way life used to be, we used to walk into churches and say prayers, but here’s Rick in the church.

[Clip from The Walking Dead (Season 2, Episode 1 “What Lies Ahead”)]

RICK GRIMES (AS PLAYED BY ANDREW LINCOLN): I don’t know if you’re looking at me with what — sadness? Scorn? Pity? Love? Maybe it’s just indifference. I guess you already know I’m not much of a believer. I guess I just chose to put my faith elsewhere; my family, mostly, my friends, my job. The thing is we — I could use a little something to help keep us going. Some kind of acknowledgement, some indication I’m doing the right thing. You don’t know how hard that is to know. Well, maybe you do. Hey look, I don’t need all the answers. Just a little nod, a sign. Any sign will do.

DR. WINSTON: Wait, Krista, that is amazing.

KRISTA TIPPETT: Isn’t that amazing?

DR. WINSTON: Well, it’s sort of like, hey, Gethsemane. I mean, God, talk to me, right? So, you know, you think here’s this like crazy show on AMC, but it is that central theological question of where is God in my suffering, right?

KRISTA TIPPETT: Yeah, yeah, and it’s absolutely explicit out there. Then, of course, he walks out of the church, he says give me a sign. This is a story we’ve seen many times, right? And then they go out into the woods; he’s with his little son and another man and they see a deer and it’s a beautiful moment of nature and you think here’s the sign and then it all goes terribly. A shot rings out. Not just the deer dies, but the child is hit as well.

DR. WINSTON: Right, which echoes back, taking my son. You know, whether it’s Abraham and Isaac or whether it’s God and Jesus. You want a sign? I’ll take your son, right? I don’t think it’s stretching to really read these deeper classic religious tropes onto the current scene because what is culture except making those tropes come alive in each generation. You know, people have been asking where is God for thousands of years and why wouldn’t we be asking the same question and why wouldn’t we want to represent it in our own language rather than in, you know, the King James version?

[Clip from Dexter (Season 6, Episode 1 “Those Kinds of Things”)]

JOE WALKER (AS PLAYED BY JOHN BROTHERTON): What would Jesus have done?

DEXTER: Seriously now.

KRISTA TIPPETT: This is a scene from the new season of Showtime’s Dexter.

DEXTER: How do you reconcile your belief in a higher power — in a god — with what you’ve done?

JOE WALKER: What difference does it make?

DEXTER: I’m just curious.

JOE WALKER: So, what — I’m supposed to defend my beliefs to you?

DEXTER: If you don’t mind.

JOE WALKER: Look … I mean … Everyone makes mistakes. They do things that they shouldn’t do. And… they’re only human. But God forgives us.

DEXTER: Really? Really, is it as simple as that? You kill someone, and God forgives you for it?

JOE WALKER: Yes!

DEXTER: So I can kill you, and God will forgive me?

KRISTA TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, with On Being — conversation about meaning, religion, ethics, and ideas. Today: “Monsters We Love.” We’re looking at the monsters — human and otherwise — who populate some spiritually and morally intriguing television right now. Zombies in particular are not only popular on the small screen. They’re the subject of a best-selling literary novel; there are zombie “crawls” on Saturday nights in American cities; there have been people dressed up as “corporate zombies” at Occupy Wall Street.

DR. WINSTON: And then, there’s something going on as well that’s related, but not so directly theological, but about morality, right? You know, it’s like what happens to morality when everything falls apart like this? And something that’s difficult or troubling or especially challenging about zombies is you can show no mercy, right? You can chop their heads off without a minute of remorse. You know what I’m saying? Like, and so Colson Whitehead, who’s just written this new novel — zombie novel.

DR. WINSTON: Right. Right.

KRISTA TIPPETT: I thought this was interesting he said, and this gets at this too. “For me, the terror of the zombie is that at any moment your friend, your family, your neighbor, your teacher, the guy at the bodega down the street, can be revealed as the monster they’ve always been.” So there’s also some pretty earthy, dark reflection on humanity that’s going on here.

DR. WINSTON: Right. That’s why zombies who are like on The Walking Deadactually looking like zombies and zombies who seem to be real people provide an interesting counterpoint. So Breaking Bad, Walter White…

KRISTA TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. WINSTON: …in some ways over the last three years, he’s become more of a zombie. He’s more and more cut off his human side and his human interactions — even as his cancer progresses — to stay alive and get one task done. And as he becomes more of a walking zombie, he’s much more comfortable killing people and living in an amoral universe.

KRISTA TIPPETT: So I have really had trouble getting into that one. I find it really hard to watch. So would you just give a little capsule of what the story there is, the plot and who he is?

DR. WINSTON: Breaking Bad is the story of a high school chemistry teacher who discovers he has terminal cancer and wants to make sure his family is taken care of when he dies. So he starts cooking up meth and selling it and he takes on one of his former students as his helper. And the show is about his descent into this criminal world of drug dealing and the implications that it has for his relationships and for his soul.

And Vince Gilligan, the creator, has said that, to him, it’s important to see that actions have consequences and to look at what happens to a person’s soul once they make certain decisions. So the character does not remain static. The very fact of him getting deeper and deeper into a criminal life changes not only the dynamics of his family, like his wife leaves him, it also changes his whole personality. I mean, he becomes more cut off, more inward, and more amoral, more able to kill lest he be killed.

[Breaking Bad (Season 4. Episode 6 “Cornered”)]

SKYLER WHITE (AS PLAYED BY ANNA GUNN): You’re not some hardened criminal Walt. You are in over your head. That’s what we tell them. That’s the truth.

WALTER WHITE (AS PLAYED BY BRYAN CRANSTON): That’s not the truth.

SKYLER WHITE: Of course it is. A school teacher? Cancer? Desperate for money?

WALTER WHITE: OK, we’re done here.

SKYLER WHITE: Roped into working — unable to even quit! Let’s both of us stop trying to justify this whole thing and admit you’re in danger.

WALTER WHITE:I am not in danger, Skyler — I am the danger. A guy opens his door and gets shot and you think that of me? No. I am the one who knocks!

DR. WINSTON: And it’s a hard show to watch. I was thinking a lot about that, about the monsters I like watching as opposed to the monsters I don’t like watching. I love watching True Blood and Vampire Diaries, but I don’t like watching Dexter and Breaking Bad as much. I mean, it’s easy to see why, right? Because, you know…

KRISTA TIPPETT: The blood in one is real and, in another, it’s not.

DR. WINSTON: Right, right. And monsters are sexy in those shows I like, whereas they’re, you know, off-putting in others. But Breaking Bad is hard to watch. You know, it takes place in Albuquerque and the scenery is dry and the dialogue is sparse and the action is bleak. It is a hard show to watch, but it does have this almost biblical pace to it and the sense that it’s dealing straightforwardly in issues of life and death.

KRISTA TIPPETT: So here’s something that I wonder about us as viewers. So this is, I mean, this is entertainment. And is there some difficult message about us as a culture or us as watchers that, on some level, we enjoy this? I don’t know if enjoy is the right word. But you know what I’m saying? What does the popularity of these things say about us?

DR. WINSTON: People want to see the basic dramas of their lives enacted. And why are passion plays so popular?

KRISTA TIPPETT: Why the crucifix?

DR. WINSTON: Right. Those central themes speak to us in dramatic ways, and so we want to see them again and again. I mean, it’s not easy watching the movie The Passion of Christ, which I suppose maybe that’s sui generis and we shouldn’t put it in there, but it’s not easy watching a passion play and yet it’s instructive and it’s meaningful. You know, if you are Jewish, it’s not easy going into synagogue and hearing the story of the sacrifice of Isaac, and yet you know you’re hearing it for a reason or it’s telling you something, or Job, for that matter. So, I think it performs a similar function. People have a hard time getting that because television is a consumer commodity, which is also entertainment. We don’t think of religion and entertainment mixing. The truth is that religion and entertainment have always mixed, you know, whether it was the stained glass windows in European cathedrals or the passion plays put on or early movies that depicted the life of Christ. Religious people have used dramatic means to get a message across.

KRISTA TIPPETT: And there is a lot of — I mean, you’ve been writing about this. There’s a lot of overt religion all over the place in a way that’s kind of new, all kinds of religion.

DR. WINSTON: Yes. There’s all kinds of religion, I have to say. Most of it’s pretty Christian. You know, whether…

KRISTA TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. True Blood is the one that really is diverse, right? It has Wiccans and…

DR. WINSTON: Yeah, that’s true, that’s true. Alan Ball is usually pretty sensitive to marginalized groups and he’s even said that, you know, the vampires can be stand-ins for gays or for any oppressed marginalized people.

KRISTA TIPPETT: Has he said that?

DR. WINSTON: Yeah, yeah.

KRISTA TIPPETT: Because that is actually — I mean, so there is religious diversity, you could say, but there’s no so much theology in True Blood, but there’s a lot of — well, there are these big existential and moral issues that get raised again about bigotry and otherness and, you know, immortality, mortality. I think they’ve done some really interesting things with that in True Blood.

DR. WINSTON: Are you thinking of anything in particular?

KRISTA TIPPETT: Sometimes it’s just the mundane moments like when Bill Compton, who’s a vampire — this feels like such a long time ago because the show has progressed so much — but when he proposes marriage to Sookie Stackhouse who’s not a vampire and she opens up a ticket to Vermont. It turns out that that’s where they legalized vampire-human marriage [laugh].

[True Blood (Season 2. Episode 12 “Beyond Here Lies Nothin'”)]

BILL COMPTON (AS PLAYED BY STEPHEN MOYER): I do have one last thing.

SOOKIE STACKHOUSE (AS PLAYED BY ANNA PAQUIN): Plane tickets? Where’s Burlington?

BILL COMPTON: It’s in Vermont.

SOOKIE STACKHOUSE: Vermont? Why would we…

BILL COMPTON: This is the other part. Ms. Stackhouse, will you do me the honor of becoming my wife? That is assuming that last night didn’t scare you off weddings for good.

DR. WINSTON: True Blood is a great example of a show, I think, that is about re-enchantment. So if you look at sort of the standard sociological critiques of society, what’s happened in industrial post-capitalist society is that we’ve lost the awe, we’ve lost the beauty, we’ve all been rationalized to the point where everything is — there’s no transcendence anymore. So what we need is our culture to reawaken us to mystery and to awe and to wonder. So here’s like this very prosaic Louisiana town, you know, with good old boys and, you know, rednecks and what do you know, but a vampire comes into the bar and, next thing you know, there’s witches and werewolves and all kinds of others.

KRISTA TIPPETT: Shapeshifters. Yeah.

DR. WINSTON: Shapeshifters. Yeah. I mean…

KRISTA TIPPETT: Fairies.

DR. WINSTON: Right. And as the characters are being re-enchanted, hopefully the audience is also, right?

KRISTA TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. I really like that.

DR. WINSTON: It’s a much more upbeat sort of idea than those apocalyptic shows we were talking about before where there’s mystery and wonder in the world, but it’s like because everything is desolate [laugh].

KRISTA TIPPETT: Yeah, if I could just ask you this straight question. I’ve posed this question and I’ve heard other people pose it in the last year. What is it with vampires? Why vampires? What do you think?

DR. WINSTON: There are reasons that are financial, there are reasons that are sexual, and there are reasons that are existential. Where shall we start?

KRISTA TIPPETT: Hmm, I don’t know.

DR. WINSTON: Sex, money or why am I here [laugh]?

KRISTA TIPPETT: Give me a quick rundown of all three of them. Start with sex.

DR. WINSTON: Vampires are sexy and they are known throughout most of the literature to be great at seduction, to be powerfully erotic. There’s something about that mixture of blood and death and eroticism that make us see them as heroic. Now obviously, all vampires weren’t that way all the time. And again, this is partly because — and now we segue into finance. Commercially, it makes more sense to have a show around a sexy vampire than one that looks like Bela Lugosi. Beyond that, vampires speak to very basic issues of what does it mean to be a human being? And a lot of these shows basically are looking to see are vampires still human? Do they still care? Do they still have emotions? Do they have morality? You know, as stupid in some ways as Vampire Diaries is — and I have to say in all honesty I love Vampire Diaries…

KRISTA TIPPETT: I haven’t watched it. [laugh] OK, so tell me.

DR. WINSTON: OK. Maybe — Vampire Diaries is a story of a small Virginia town. You know, it’s sort of like True Blood. It’s a small Virginia town that, even though it seems very straight and normal, it’s just chock full of vampires and shapeshifters and witches, and they’re all like breaking out in high school. The protagonist who is like a high school senior is torn between two vampire brothers. And the question is can she redeem their humanity? Can she get them to claim that part of themselves which they have let atrophy, and she believes is necessary if they are to be loving partners.

So in a world where people do amoral things to each other, rather than think about doing shows on Bernie Madoff or folks like that, which you have done anyway, but how many can you do? Making your vampires who are sexy people emblematic of those moral struggles makes for good drama. So I think they’re sexy, you know, they evoke questions of basic humanity, and there’s also some things that are just striking about them. They live forever, you know, they have supernatural powers, they are monsters, but they’re not monsters.

[Vampire Diaries (Season 2, Episode 12 “The Descent”)]

DAMON SALVATORE (AS PLAYED BY IAN SOMERHALDER):What do you want to hear? That I cared about Rose? That I’m upset? Well, I didn’t and I’m not.

ELENA GILBER (AS PLAYED BY NINA DOBREV): There you go. Pretending to turn it off. Pretending not to feel. Damon, you’re so close, don’t give up!

DAMON SALVATORE: I feel Elena. OK? And it sucks. What sucks even more is that it was supposed to be me.

ELENA GILBERT: You feel guilty.

KRISTA TIPPETT: I did some extra hardcore TV watching to get ready for this conversation with Diane Winston. In our unedited interview, we talked about all kinds of shows and other themes, like the retro cultural therapy of Mad Men and Pan Am — as well as the formative role Star Trek played in both of our early television lives; and what she calls the “Women Gone Wild” witchiness of a character like Nurse Jackie. Write us about the shows and plot lines that make your heart race and your blood curdle — and reach us in all the places where you’re already talking television and everything else: on Facebook or Twitter; or, if you like, leave a comment on our show page for “Monsters We Love” at onbeing.org.

[Music]

KRISTA TIPPETT: Coming up, how God is making a serious TV appearance in surprising ways and places — like 24‘s successor, Homeland, and HBO’s Enlightened.

I’m Krista Tippett. This program comes to you from APM, American Public Media.

[Announcements]

KRISTA TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett. Today, On Being: “Monsters We Love — TV’s Pop Culture Theodicy.” I’m catching up with Diane Winston, as I do from time to time. She watches media and religion at the University of Southern California. And we’ve been talking about the wave of vampires, zombies, and soulless characters who happen to be human in the current crop of TV. But there’s also a really telling shift of social commentary since she and I spoke a couple of years ago. For example, in the difference between 24 and the newest creation of some of 24‘s writers, Showtime’s Homeland.

KRISTA TIPPETT: Are you watching that? Homeland?

DR. WINSTON: Yes. I am addicted to that show.

KRISTA TIPPETT: It’s good, isn’t it?

DR. WINSTON: It’s very good. It’s one of those shows that was a little hard to watch at first because the characters were not tremendously attractive in either — to look at or in terms of their actions.

KRISTA TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. WINSTON: But the more I’ve watched it, the more I’ve appreciated Clair Danes’ performance and also — what’s the name of the male actor? Is that Damian Lewis?

KRISTA TIPPETT: The Sergeant Brody character?

DR. WINSTON: Yes, Sergeant Brody. He’s really good too.

KRISTA TIPPETT: So the story there is that a — you know, I have to say when I was hearing reviews of it before it aired, I thought how can you carry a plot with that, right? That’s there’s an American soldier who was taken prisoner and has been released, and so he comes home a hero. Claire Danes is FBI, right? or Homeland Security?

DR. WINSTON: She’s CIA, I think.

KRISTA TIPPETT: CIA agent who, just before this Sergeant Brody was released, was whispered in her ear by a contact she has in some prison somewhere, Islamabad, someplace like that, that an American soldier has been turned. And so she suspects this guy who’s now an American hero of being part of the enemy. But unlike Kiefer Sutherland, who was just full of certainty at every turn, right, the classic hero, she’s manic depressive, she’s very strong and interesting and stubborn, but she’s in the dark and so are we about what’s really going on.

DR. WINSTON: She’s a little crazy, don’t you think?

KRISTA TIPPETT: She’s crazy, yeah. So in terms of religion — and this is a very different way — direction for this to go. In terms of this overt religiosity, I mean, let’s say in 24 Muslims were bad guys, but there was no real investigation of what it meant to be Muslim, right? It was an identity. Basically, Muslims were terrorists. This perplexing figure of Sergeant Brody — and we really still have no idea what’s going on inside him. We know he’s been tortured, we know that he’s a human being who’s struggling and there’s a moment in the second or third episode, which comes out of the blue. where we know he made a trip to the store and he bought something and we don’t know what he bought. And he goes into the garage and he pulls out a prayer rug and he washes his hands and he kneels and he prays.

[Clip from Homeland]

SERGEANT NICHOLAS BRODY (AS PLAYED BY DAMIAN LEWIS): [reciting Muslim prayer]

KRISTA TIPPETT: Did you see that?

DR. WINSTON: Yes, I did. It was almost like a Rorschach test about that character. What did you think when you saw him do it?

KRISTA TIPPETT: Well, you know, I thought — Nancy Franklin did a review of this in The New Yorker, and she really put her finger on what I felt, which is “in that moment, we felt both more worried and less worried about him than we had before.” But the human effect it had was here’s this guy who’s been tortured, he’s clearly struggling to be back home with his family, to be back in the world. He felt more at peace than he had at any moment since you’d been introduced to him. There was something quite beautiful and peaceful about it.

DR. WINSTON: That’s so interesting, Krista, because when I saw it, I thought to myself, “Oh, my gosh, Clair Danes is totally right. The guy is a Muslim sleeper-killer.” [laugh]

KRISTA TIPPETT: And see, well — I thought it was such interesting complexity they introduced because so now we know — I think all we know is that, in those eight years of captivity or whatever, he converted to Islam or he began to pray as a Muslim.

DR. WINSTON: Now that you say it, I can see it. It’s just that I think Americans at this time and place are predisposed to be so suspicious of Islam.

KRISTA TIPPETT: Yeah, but I think it’s actually dramatically challenging that, not by wrapping it up, but just kind of throwing out a challenge. Could this American hero have converted to Islam…

DR. WINSTON: Without betraying his country?

KRISTA TIPPETT: Without betraying his country? And this is part of what’s holding him together.

DR. WINSTON: Yeah. I think that show is great and it’s interesting and I’m going to watch it now with more appreciation because I guess that I am the kind of knee-jerk viewer who thought Islam was being used as a sign of disloyalty. So the fact of it being something which is holding him together and has constituted a new positive identity just never struck me. It would be great if you’re right.

The more I think about media, the more I come to believe that we live our lives through media and that people spend something like five to seven hours a day watching television. It’s a place where we learn who we are and we learn who we are with and we figure out what’s important to us. So on the one hand, it’s easy to trivialize TV, but I really do believe we’re looking at central concerns of many Americans today as they deal with economic crises, as they feel their life’s out of control, as they feel like, you know, they’re living in a world without hope. They are The Walking Dead, as you said. These shows, even as they on the one hand trivialize some of these issues by the very fact that they’re commercial entertainment, they’re still bringing them into the public square for discussion. So, yes, that was my little soapbox.

KRISTA TIPPETT: Well, OK, and then you and I are talking about — well, the shows we’ve talked about in this conversation are mostly quite aesthetically sophisticated storytelling and drama, cinema really. I mean, I guess I just have to ask. People who watch five to seven hours of television a day, I mean, some of that, including what my children watch, is reality TV, which is in a whole other category.

DR. WINSTON: Right.

KRISTA TIPPETT: I mean, how does that fit into what you just said about the meaning-making function of this stuff?

DR. WINSTON: You know, I don’t watch enough reality TV to say anything tremendously smart about that. I do think, to some extent, people watch reality TV, not Ace of Cakes or Home Décor, but other kinds, in order to see models and to understand how people make decisions. I mean, whether they’re watching the Kardashians or whether they’re watching Real Housewives, it’s entertaining. But I think it also offers them a big canvas on which they can project no, I don’t want to be like the Kardashians or maybe I’d like their house, but their values are screwy.

KRISTA TIPPETT: Yeah, I wonder if reality TV in some ways is more escapist than, you know, these vampires we’ve talked about where they’re actually really big existential issues at play even though it’s also high drama.

DR. WINSTON: Right. It also seems to me, oddly enough, more like wish fulfillment. Whether you’re learning how to dress or bake cake or survive on a vacation, it’s basically extending the material functions of your life one way or the other. I mean, it’s not about, as you say, those existential questions. It’s more about how do I take care of myself in the here and now or how do other people take care of themselves in the material level.

KRISTA TIPPETT: Those of you who are watching Homeland will know that its religious plot thickened before this interview went to air. It’s too simple just to say that I was right about Sergeant Brody. But here you go:

[Clip from Homeland (Season 1, Episode 7 “The Weekend”)]

CARRIE MATHISON (AS PLAYED BY CLAIRE DANES): What goes on in your garage? Why do you go there so late at night? So early in the morning?

SERGEANT NICHOLAS BRODY: To pray.

CARRIE MATHISON: You’re Muslim?

SERGEANT NICHOLAS BRODY: Yeah. You live in despair for eight years, you might turn to religion too. And the King James Bible was not available.

KRISTA TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being — conversation about meaning, religion, ethics, and ideas. Today, with media and religion expert and TV aficionado Diane Winston.

KRISTA TIPPETT: And I would like to talk about Enlightened, which is this new half-hour weekly HBO show. It’s HBO, right? With Laura Dern. Have you been watching that?

DR. WINSTON: Yes, and do you know the back story of this?

KRISTA TIPPETT: No.

DR. WINSTON: OK, this is great. Laura Dern and Mike White created it. Mike White is the son of Mel White who was the conservative Christian minister who ghost-wrote books with Jerry Falwell and others and then came out and, you know, embraced his gay self. So Mike White grew up in this house and Mel White came out to the family years before he actually came out to everybody else. So he was living in this world where his father was a conservative minister in Pasadena, but also had this deep secret. Mike White has said that, at his home, his father often used Hollywood movies as a way to talk about spiritual issues.

Now Mike White has done a number of movies with Jack Black and Laura Dern and other folks. In the middle of doing a TV show a couple of years ago, he had a nervous breakdown. And he has said that Enlightened sort of is a riff on what happened to him. It’s not one-to-one correspondence, but his experience of kind of breaking down and then finding yoga and Buddhism helped to shape the material. So doesn’t that make it like a whole different thing?

KRISTA TIPPETT: It’s really interesting.

DR. WINSTON: And, and the other thing that’s so cool is, the industry where she works, Abaddon. Abaddon, in the Hebrew Bible, is the underworld and, in the Book of Revelation, Abaddon refers to the angel of the dark abyss. So the whole show is like going on, on a lot of different levels. But after reading about Mike White, I like the show better because I wasn’t sure if it was a parody up and up or whether it was trying to take on some of these issues. It seems to be skating on the edge of both. I think they really are asking, how do you live in this world without succumbing to desperation or unhappiness or greed? I mean, how do you find a way to live in this world where you aren’t a cog in the system, yet you can still lead a somewhat normal life?

[Clip from Enlightened (Season 1, Episode 2 “Now or Never”)]

AMY JELLICOE (AS PLAYED BY LAURA DERN): [sound of fingers tapping on keyboard] Change will come. Maybe not today. Maybe not tomorrow. But it will come. You have to believe. I close my eyes. And see a better world. People there are fearless and connected. They are my friends. I am there. I am free. And this earth itself is healed. And where nothing suffers.

KRISTA TIPPETT: You know, you have written a lot and we talked about these overt religious themes that are there in really interesting ways even in something like The Walking Dead, I mean, the crucifix and the death of the son and all of it. But there’s a way in which this show feels to me also like a maturing of how spirituality has come into the culture in the last 20 or 30 years. It’s nodding to the fact that there’s a flaky side to this [laugh], right, but it’s also nodding to the fact that there’s something that’s really meaningful for people and somehow it’s acknowledging that in a new way.

DR. WINSTON: I can’t think of many shows that tackle this, can you? I mean, it feels new to me.

KRISTA TIPPETT: Without just making fun of it.

DR. WINSTON: Right, without just making fun of it. It takes her real breakdown and putting herself back together seriously. And you do identify with who she wants to be. She wants to be an agent of change. Who doesn’t want to be an agent of change?

KRISTA TIPPETT: Yeah, exactly. So when we talked a couple of years ago, you were talking about where you were especially with your students about all the different ways people inhabit and work with the television that’s meaningful for them. I mean, that’s just exploded even in those years. I don’t think Twitter was something anyone did back then.

DR. WINSTON: Part of why — and I’m so glad you asked me this question because I should have said it. Part of why television has become even more powerful as a place for working out social and cultural issues is because we’re no longer isolated intelligences watching in our own homes. So I am struck by the number of blogs that work on issues around Dexter or work on issues around zombies or work on issues around vampires, asking the questions that we’ve been talking about for the last hour or so.

What does it mean to be human? What is morality? How does justice figure into love? How do I know what’s spiritual? Can people change? These very basic questions are debated by people now not only in forums or through blogs, but also Twittering on them. Whenever I Twitter on a TV show, you know, I get most responses to almost anything else I do, or posting on Tumblr or, you know, going through Buzz. I mean, there’s so many ways to get these ideas out and so many people who want to talk about them.

You know, people all over the world can debate whether or not, you know, the Muslim conversion in Homeland is a cynical ploy or a deep truth. So the fact of our mediated experiences further and deepen the spiritual connections that we are making through culture and through television in particular. And the fact that this goes on in our homes oftentimes or the fact that you can toggle between watching a TV show on your computer and Twittering at the same time, it just makes it even more immediate for people.

KRISTA TIPPETT: Diane Winston is on Twitter @dianewinston; we are @Beingtweets. Find us there, or at facebook.com/onbeing or at onbeing.org, and tell us what shows you like that we just missed. Tell us about the TV that matters to you, what it says about who we are, what we fear, what we aspire to be.

[Music]

KRISTA TIPPETT: Diane Winston holds the Knight Chair in Media and Religion at the Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism. That’s at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. She edited Small Screen, Big Picture: Television and Lived Religion. Her media and religion blog is called the SCOOP. And you can listen to this entire conversation again or our unedited interview at onbeing.org. We’ll let Laura Dern take us out with another scene from HBO’s Enlightened.

[Clip from Enlightened (Season 1, Episode 1 “Pilot”)]

AMY JELLICOE: So it was one morning, super early and I was meditating on the beach. You’re giving me a smirky look.

LEVI (AS PLAYED BY LUKE WILSON): No, I didn’t say anything.

AMY JELLICOE: I want you to be open.

LEVI: I’m wide open.

AMY JELLICOE: Anyway, I decided to get in the water and a sea turtle just passed by, big, beautiful sea turtle.

LEVI: Wow. That’s cool.

AMY JELLICOE: I felt this presence all around me. It was God. Or it was better than God. It was — something was speaking to me. It was saying — this is all for you. And everything is a gift, even the horrible stuff.

LEVI: I know what you mean. I kind of had the same thing happen. I was at Red Rocks on some mescaline. [Laughs]. No, I’m glad that happened to you. I am. To the presence of God, really.

AMY JELLICOE: Presence of God.

KRISTA TIPPETT: This program is produced by Chris Heagle, Nancy Rosenbaum, and Susan Leem. Anne Breckbill is our Web developer.

Trent Gilliss is senior editor. Kate Moos is executive producer. And I’m Krista Tippett.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.