Diannely Antigua

Another Poem about God, but Really It’s about Me

“You would’ve made a lousy nun.” The narrator of Diannely Antigua’s “Another Poem about God, but Really It’s about Me” overhears these words, and they jolt her into contrasting her life experience with the limited archetypes offered by her church — good daughter, good sister, holy woman, whore. Which of these has she been? Where does her devotion lie? And what virtue can she claim?

We’re pleased to offer Diannely Antigua’s poem and invite you to subscribe to Pádraig’s weekly Poetry Unbound Substack newsletter, read the Poetry Unbound book, or listen to past episodes of the podcast. We also have two books coming out in early 2025 — Kitchen Hymns (new poems from Pádraig) and 44 Poems on Being with Each Other (new essays by Pádraig). You can pre-order them wherever you buy books.

Guest

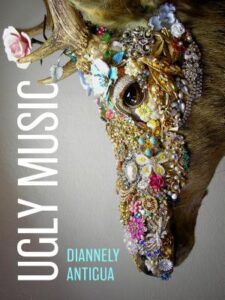

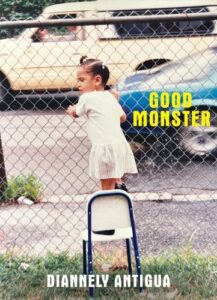

Diannely Antigua is a Dominican-American poet and educator who was born and raised in Massachusetts. Her debut collection, Ugly Music, won a 2020 Whiting Award and the Pamet River Prize. She received her MFA in Creative Writing from NYU, where she was awarded a Global Research Initiative Fellowship to study in Florence, Italy. She was a finalist for the 2021 Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Poetry Fellowship and the recipient of fellowships from CantoMundo, Community of Writers, and the Academy of American Poets. Her work has appeared in the Best of the Net Anthology and has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize. She currently serves as the poet laureate of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, and is the host of the podcast Bread & Poetry. Her most recent poetry collection is Good Monster.

Transcript

Transcription by Alletta Cooper

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama. And for a long time, I thought I was going to become a priest. I never did. But with reflection years later, I now realize that possibly one of the things I wanted more than becoming a priest was to be a priest who left. I have such a relationship of tension with religion that I can’t imagine I’d have lasted more than a few years. I think I’d have liked the work, but I have a disproportionate dislike of certain forms of authority. Hidden in one desire is often another desire. And often my complex relationship with a structure can manifest itself in ways that are sometimes self-destructive and that, ask me to go much deeper. Poems can help you do that by digging through and looking at all the layers that can be present in a single desire.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Another Poem about God, but Really It’s about Me” by Diannely Antigua

“You would’ve made a lousy nun, the woman

on the A train says to the person on the other end

“of the phone. I laugh to no one and imagine

what a lousy nun would do—maybe sneak

“a lover into her room on Ash Wednesday or take

off her wedding ring from God, let the sun

“touch the unveiled skin. I was never

a nun, but I was called Sister, and Brothers

“were not allowed to do more than shake

my hand. I was called daughter when the pastor

“kissed my cheek, when I was worth more than rubies.

I was a good Sister for a decade—I was

“good. After I left, I still prayed to all the Fathers

who weren’t mine. I opened my mouth

“to their wisdom, and in my tongue was the law

of kindness. I became their Mary

“Magdalene—holy by day, whore by night—

perfuming the feet of every man named

“Jesus. After I left, I stayed devout—

devout to recklessness, devout to taking

“out my virgin. I don’t remember craving

anything so much as my own destruction.

“It was beautiful to watch from the bleachers

of my mind, separating myself from

“all the Sisters inside me. In Proverbs,

it is virtuous for a woman to work willingly

“with her hands. I only wanted to bring virtue

unto my name when I held each new body in my palms.

“I only wanted to bring virtue when I hid

in the bathroom, slapped my face.”

[music: “Creatures of Myth” by Gautam Srikishan]

Diannely Antigua is a Dominican American poet who, throughout her book, makes references to a version of Christianity that’s Pentecostal. There’s a number of poems that are titled similarly to this, another poem about one thing, but really it’s about another thing. And this one is titled “Another Poem about God, but Really It’s about Me.” It could be, perhaps, that you could title the poem as well, “Another poem about God, but really it’s about sex.” Sex, for some — maybe all of us at times — it can be difficult to talk about well. And often it appears in conversation when we’re talking about something else. And so sometimes, perhaps, if you said, We’re going to talk about sex, people might talk about anything but. But instead of which we’re talking about nuns, or she’s imagining talking about nuns, and suddenly sex shows up in pleasurable ways and risky ways and secretive ways throughout the story of the poet’s own life as well. It starts by a projection of a nun’s sneaking “a lover into her room” or the “wedding ring from God.” But then we see restraint in the story of herself that the brothers weren’t “allowed to do more than shake / my hand,” is how she says it. And that is a restraint on the brothers because of an imagination of purity. She speaks about that there clearly is a before and an after. There’s this line, “I was a good Sister for a decade—I was // good. After I left. I still pray to all the Fathers.” And so you hear that there has been a change of religious belonging and perhaps a change in the way she might see herself, but clearly a change in the way where she might be seen by others — by that Father of the pastor, by those Brothers in the congregation, by anybody else in the congregation, too.

[music: “Daybreak” by Gautam Srikishan]

There’s some absolutely beautiful, delicious, magnificent, wild line breaks throughout this poem. One of the line breaks is “I became their Mary.” And then there’s a line break. In fact, a stanza break. This poem is in a whole sequence of couplets, and it goes from one stanza to the next. “I became their Mary // Magdalene.” And by leaving this space there, Diannely Antigua is allowing us to think, Which Mary are we going to talk about? Mary who was known? Mary the virginal mother of God? Mary the woman who’s assumed to have worked in prostitution? Who is she going to be? In a way, the story of how the various Marys of the gospel traditions are spoken of reflects the ways women are spoken of often. Do you know, are you going to be the harlot? Are you going to be the mother? Are you going to be the maiden or the crone? Or are you going to be removed? These, these singular options, really that, present themselves for archetypes of woman as they’re often presented in certain readings of the gospel texts — that is a, a very limited imagination of the fullness of being human. And so I understand and applaud, and admire hugely the way within which through line breaks and through pushing back and through eros and through daring and risk, but also you hear self-destruction and pain. I understand how all of those energies are coalescing in this poem.

Another line break references the pastor. “Brothers were not allowed to do more than shake / my hand. I was called daughter when the pastor” and there’s another stanza break here — which allows us, even for a microsecond when you’re looking at it, to wonder what’s going to happen. “I was called daughter when the pastor // kissed my cheek.” And then “I was a good Sister for a decade—I was” — another stanza break, and we’re wondering what’s going to happen? “I was // good” is what she says. “After I left, I still pray to all the Fathers / who weren’t mine. I opened my mouth” — stanza break. What’s going to happen? There’s the anticipation — “to their wisdom.” And by doing this, it’s culminating in drama. It’s demonstrating extraordinary skill of poetics, but it’s also showing a certain plot line is delivered and somebody is trying by frustrating or titillating or changing expected narratives to open up the restrictive cages of the archetypes, limited as they are, that are presented.

[music: “Into the Earth” by Gautam Srikishan]

So much of the human condition is about living with competing forces in ourself. Life is complicated enough without us making it more complicated for ourselves. And also, our structures increase that complication, too. I see the internalization of something that actually isn’t internal. “I don’t remember craving / anything so much as my own destruction” that you see toward the end of this powerful poem. The systems within which she is operating seem to be ones that are actually going to achieve fulfillment by seeing members of a congregation, especially female members of a congregation, struggle in the sense of their own self-destruction. And that that pushing and imagining that purity of a very particular interpretation needs to rest in the bodies of certain members of the congregation. That is bound to cause an experience of tension. By setting up this particular form of belonging as the pinnacle of the demonstration of your faith, it does mean that the narrative is, that it’s all downhill from here. And I see this happening too in that line. “I don’t remember craving / anything so much as my own destruction.” If you’ve been told it’s either here or destruction, probably eventually, you’re likely to choose some of your own destruction, even against yourself.

And some of that tension occurs in the next stanza as well. “It was beautiful to watch from the bleachers / of my mind.” We see this separation. She’s seeing some kind of game, some kind of sport happening, some destruction happening on a field, and she’s also up in the bleachers watching that. We see the split-self. We see the self that doesn’t know, Who am I? How am I supposed to be? That pain is so understandable for so many of us who have come out from backgrounds that have given us very, very limited options as to who we can be.

[music: “Ashed to Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

There’s a threefold repetition of virtue toward the end of the poem. And a reference too to the Book of Proverbs that you find in the Hebrew Bible. “In Proverbs, / it is virtuous for a woman to work willingly // with her hands.” Chapter 31 of the Book of Proverbs speaks about “Who can find a virtuous woman? for her price is far above rubies.” So with that reference towards the end, we’re also catapulted back to the beginning of the poem, realizing that Diannely Antigua has peppered references to biblical imaginations of womanhood throughout the text of her poem. And Proverbs 31, the chapter about the virtuous woman, speaks about the woman’s husband and her own industry, how she provides food and plants a vineyard. And then it finishes with the following lines. “Give her of the fruit of her hands and let her own works praise her in the gates.” “Give her of the fruit of her hands.” We see that Diannely Antigua is speaking about the fruit of her hands, and you see how she is caught in the moment, continuing to be committed, in an awful sense, of manifesting this sense of tension in herself in the final line. “I only wanted to bring virtue when I hid / in the bathroom, slapped my face.” She’s punishing herself or trying to wake herself up. I don’t know which, maybe both. The work of her hands is that she’s trying to, perhaps, bring herself into her own body; to bring herself into the world from which she’d been separated through a particular way of looking at womanhood, through a particular way of looking at sexuality, through a particular way of looking at the human condition.

[music: “Family Tree” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Another Poem about God, but Really It’s about Me” by Diannely Antigua

“You would’ve made a lousy nun, the woman

on the A train says to the person on the other end

“of the phone. I laugh to no one and imagine

what a lousy nun would do—maybe sneak

“a lover into her room on Ash Wednesday or take

off her wedding ring from God, let the sun

“touch the unveiled skin. I was never

a nun, but I was called Sister, and Brothers

“were not allowed to do more than shake

my hand. I was called daughter when the pastor

“kissed my cheek, when I was worth more than rubies.

I was a good Sister for a decade—I was

“good. After I left, I still prayed to all the Fathers

who weren’t mine. I opened my mouth

“to their wisdom, and in my tongue was the law

of kindness. I became their Mary

“Magdalene—holy by day, whore by night—

perfuming the feet of every man named

“Jesus. After I left, I stayed devout—

devout to recklessness, devout to taking

“out my virgin. I don’t remember craving

anything so much as my own destruction.

“It was beautiful to watch from the bleachers

of my mind, separating myself from

“all the Sisters inside me. In Proverbs,

it is virtuous for a woman to work willingly

“with her hands. I only wanted to bring virtue

unto my name when I held each new body in my palms.

“I only wanted to bring virtue when I hid

in the bathroom, slapped my face.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Chris Heagle: “Another Poem about God, but Really It’s about Me” comes from Diannely Antigua’s book Good Monster. Thank you to Copper Canyon Press who gave us permission to use Danielle’s poem. Read it on our website at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Eddie Gonzalez, Lucas Johnson, Kayla Edwards, Tiffany Champion, Cameron Musar, and me, Chris Heagle.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions.

This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. Open your world to poetry with us by subscribing to our Substack newsletter. For links and to find out more visit poetryunbound.org.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.