E. Ethelbert Miller

Black & Universal

A poet and self-described literary activist, E. Ethelbert Miller attended Howard University in 1968 — the age in which Black Power was finding its voice. He has remained there ever since, observing and making sense of the trajectory of black history and culture. He pushes at the parameters within which mainstream America routinely sees what he calls “blackness.”

Guest

E. Ethelbert Miller is Director of the Afro-American Studies Resource Center at Howard University and author of two memoirs and many books of poetry.

Transcript

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “Black & Universal.” My guest E. Ethelbert Miller is a poet and self-described literary activist at Howard University. We’ll explore his playful and challenging take on the evolution of blackness in the last half century, not the color of skin, but the color of ideas, artistic, political and spiritual.

E. ETHELBERT MILLER: This is what I feel sometimes, you know, African Americans can play a key role. You know what it means to be an outsider. You know what it means to be oppressed, but you also know in terms of, you know, how to move beyond that. This is what people, I think, around the world look at or used to look at when they would look at jazz or blues. They would see this universal sound and they would see, okay, I see the hurt, the pain, but I also see the joy and hear the joy and the celebration. You know, teach me to play that music.

TIPPETT: This is Speaking of Faith. Stay with us.

[Announcements]

TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett. E. Ethelbert Miller is a poet, self-described literary activist and long-time director of the Afro-American Studies Resource Center at Howard University. He first went there when it was a crucible of a new kind of black identity in the 1960s. We’ll explore his experience of the African American history that has evolved ever since. In writing and in life, his voice resembles a jazz riff more than a linear narrative.

At once playful and challenging, E. Ethelbert Miller pushes at the parameters within which mainstream America routinely sees what he calls “Blackness,” artistic, political and spiritual. We’ll also hear the words and art of others, including Malcolm X, Charles Johnson, Lucille Clifton and John Coltrane.

From American Public Media, this is Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas. Today, “Black & Universal,” meeting E. Ethelbert Miller.

E. Ethelbert Miller is the author of nine books of poetry and two poetically wrought memoirs. That E. stands for Eugene and this was what people called him for the first 18 years of his life. He landed at Howard University as an undergraduate in 1968, the moment in which Black Power was finding its voice, but he grew up in the South Bronx in a West Indian immigrant family and, as he describes it, his parents were far more immersed in that culture and more concerned with putting food on the table than with what was happening in far, far away Selma or Birmingham. “Although I was saddened by the April assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.,” Miller has written, “I did not mourn his death as something which had affected my immediate family.”

MR. MILLER: So when I came to Howard, I was sort of baptized by this black college. You know, people wearing Afros. The university had just had a major student takeover, so it was a radical departure. You know, I remember seeing Stokie Carmichael walking across the campus. I mean, one book that I had packed was Black Power by him and Charles Hamilton. So my Afro was growing a little bit and I was beginning to connect with that part of me that I didn’t know about.

TIPPETT: As E. Ethelbert Miller describes this awakening, it was more poetic than political, or rather, his political consciousness came to life in the fusion of arts and identity. His imagination was seized by the Black Arts Movement, the literary and artistic expression of the Black Power Movement. Writing and becoming a writer transformed his entire world view. He began, he’s written, “to think about blackness, not the color of my skin, but the color of ideas.” So with that as a focal point and after these four decades, I wondered where his imagination goes when he hears the phrases African American culture or Black History Month.

MR. MILLER: Well, my imagination goes in terms of how these terms have changed over the years, you know. You move from being colored to Negro, to Black, to African American hyphen or without a hyphen, you know. These are terms, I think, that for people like myself who are activists also had certain political connotations, you know, where you would talk to somebody and say, “Well, that person’s a ‘Negro.'” You know, you put that in quotes because of their political outlook on things.

Or for example, you realize that you fall back on a term like black because it is a term that can embrace people of different nationalities. For example, someone’s who’s Jamaican is going to emphasize their national identity the same way somebody is Cuban. So what happens, they may be black, but they’re not going to say “I’m African American” because they’re Jamaican. We see this, for example, with Barack Obama. Barack Obama is African American, you know, in terms of …

TIPPETT: … truly African American.

MR. MILLER: Truly African American [laughter], right. And then you see how some people go, “Well, you know, he’s a little cut off from the civil rights movement in the South.” Yeah, but he’s African American. So these terms become problematic, but at the same time, like most terms or labels, you don’t want them to exclude people or be things in which you define in such a way that you can’t get out of the box again.

TIPPETT: You know, here’s what I’m also interested in and I think you have such an expansive perspective on this from all your years at Howard and what you’ve done, what you’ve created in your working life, also in your writing life. I think that there are some predictable characters in the American lexicon and, you know, people who you talk about as well, Langston Hughes, James Baldwin.

But I wonder who is very formative for you? I would like to know some people, some writers, some thinkers, some activists who for you are absolutely central to the African American experience of your lifetime, but maybe aren’t as well-known in the wider culture. Who do you wish were in that imagination …

MR. MILLER: … well, I’ll tell you, some of them are not African American, but I would say two people. One is Charles Johnson, the novelist who lives in Seattle, because he is so extremely wide read, you know, and who is a practicing Buddhist. He always can give me a sense of that moral, you know, compass that I’m trying to follow. The other person who I admire is Doug Brinkley, the presidential historian. I just admire the guy because of his productivity, you know.

Looking back over my life, the Pan-Africanist and scholar CLR James is key. Then spiritually, I would say, because I had a chance to actually meet him, that would be Julius Nyerere who was President of Tanzania.

TIPPETT: Right. Mm-hmm.

MR. MILLER: I would actually take his name and shorten it and give part of it to my son. But I was always impressed by just the great and just the spiritual aura that this man had, so I was very happy meeting him, you know, during my life.

TIPPETT: It’s an interesting moment for us to be having this conversation because we’re right about the year mark of Barack Obama’s presidency. I’d like to draw you out a little bit more. You touched on this a minute ago. But how Barack Obama, just his person as well as his accomplishment, has influenced the language and meaning of blackness.

MR. MILLER: Well, you know, what happens is that we could go back and look at how many people didn’t think he would be in this position, you know, white as well as black. So, he definitely, you know, surprised people in terms of his accomplishment and his achievement. I think it’s phenomenal. But, you know, one can’t go back and say, okay, because Obama is president, there’s no more racism. You know, I feel that Obama is not necessarily the proper tool to measure, you know, race relations. Why we use him as that, it’s like using a ruler as a wrong instrument, you know, measurement.

TIPPETT: So you don’t buy the language of post-racial society and that he represents a post-racial society?

MR. MILLER: No. I feel that what Obama shows you, and this is how I measure social movement, I feel that Barack Obama shows you that white people have changed in the United States, okay? That’s the first. The same way, for example, if I want to measure the impact of the civil rights movement in the South, I go and I look at white people and I look at how they might be different from their grandparents. If I want to look at the success of the woman’s movement of the ’70s, I look at the changing consciousness of men, okay?

TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. MILLER: So when I look at Barack Obama, I’m saying, “Wow,” you know. I mean, my wife is from Iowa. I went out to Iowa one year after the Iowa primary with my daughter and I said, “Jasmine, how did he win this? What happened here?”

TIPPETT: So let me ask you this. Even if you don’t want to take Obama as the center point of the discussion about race, you’re saying that that’s not the appropriate discussion to have around him. Talk to me about how you have observed the difficulty that we still have talking about race, or as you’ve said, talking about it or not talking about it.

MR. MILLER: Well, this is the difficulty. If you look at black people, all of a sudden, Obama is ours. You know, we want Obama to have this agenda. Well, really he doesn’t have to be that way. We are not really responsible for him and his campaign being as successful as it was. What we have to realize is that we’re one part of America, you know, of people who decided that this was the person that we wanted to put in this office.

But what we have to do as African American people, we have to realize, wow, there is a point in which white people will meet us halfway, okay? And another thing, if, for example, a policeman hits somebody up side the head in Poughkeepsie, you know, Tempe, whatever city, it’s not going to set the race back, you see [laughter]?

TIPPETT: All right, and is it going to set the race back if Barack Obama turns out not to be a good president?

MR. MILLER: No. The same way if Spike Lee puts out a bad movie is not going to set back cinematography. You see what I’m saying? You know, it’s like Jackie Robinson. Yes, you can make an error. You know what I’m saying? In 2010, we are still looking at black people as if they represent everybody.

TIPPETT: What do you mean by that?

MR. MILLER: You see?

TIPPETT: No. What do you mean by that?

MR. MILLER: Well, what happens is …

TIPPETT: … oh, you mean that one black person represents every black person?

MR. MILLER: Everybody, right.

TIPPETT: Okay, mm-hmm.

MR. MILLER: So it’s like saying if Obama is a bad president, we’ll say he was just not qualified [laughter]. See, I’m a Larry Doby type of guy. I’m like, you know, the guy who integrated the American Baseball League that nobody remembers [laughter]. You know what I’m saying? Everybody says, oh, Jackie Robinson, Jackie Robinson. Well, Larry Doby, man. I’m waiting for the next black president to come along and do something. Maybe Obama’s just John the Baptist; he isn’t Jesus. He’s just John the Baptist.

TIPPETT: Okay. I’d like to talk about poetry. For you, I think, talking about poetry doesn’t mean that we stop talking about politics.

MR. MILLER: Right.

TIPPETT: In fact, I mean, here’s something you wrote that I think is very intriguing and beautiful, you know, that you said, “I did not write to escape from my surroundings. I write to embrace my neighbor. It is the politics of imagination which provides me with the vision of the type of world I would like to live in.” In my ears, that’s also a wonderfully religious or spiritual statement.

MR. MILLER: Well, it is because, you know, what I’ve been telling people — this is, I think, our responsibility of what I call language work that writers have to do. You know, we have to change our vocabulary, you know. I feel that if, for example, we can bring back into our vocabulary the beloved community that people like Martin Luther King or John Lewis still talks about, I think that’s a positive thing.

If, for example, words like nonviolence can become part of our vocabulary again, I think that’s a positive thing. What happens, certain words have just been forgotten and what happens is that we don’t even realize the importance of what these words meant. I mean, no one talks about a utopian society anymore. Even though when we look at some the amazing things in terms of science and technology, it seems like we’re moving in that direction.

TIPPETT: The beloved community is also a scriptural reference, right?

MR. MILLER: Right, right. I think that there are things, for example, we’re battling right now over the proper definition of Jihad because Jihad is pretty much a spiritual development.

TIPPETT: Right. We’re very mixed up in our language with Islam. That’s absolutely true.

MR. MILLER: And you have to say, okay, make room for this. This is where the language becomes necessary. We don’t use the language. We don’t even see these people, or we see them a certain way. The same way when we hear about somebody saying, well, there’s not that many black people playing baseball. You mean, English-speaking black people. You know what I’m saying [laughter]?

TIPPETT: Right, right.

MR. MILLER: And this is what I call language work. We need to make sure that poets or fiction writers that we interact with politicians and others in terms of making sure that the language is always clean.

TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, “Black & Universal.” Much of E. Ethelbert Miller’s own writing is essentially spiritual and with an eclectic range of influences, Muslim and Buddhist as well as Christian. All of these traditions played a part in the formation of a new kind of Black consciousness in the crucible of the 1960s. Several generations of young black men, in particular, had already been galvanized by the nation of Islam, of Elijah Muhammad, Louis Farrakhan and Malcolm X, a merger of Islamic faith with nascent themes of Black Power.

But in the 1960s, the Black Arts Movement was also discovering Sufi poetry that bespoke a universalist core of Islam. In the decades that followed, the majority of African American Muslims transitioned to orthodox non-exclusionary Islam under the leadership of Elijah Muhammad’s son. They were pointed in that direction already in 1964 by a dramatic change in Malcolm X’s understanding of Islam and race after he made the hajj or pilgrimage to Mecca.

In the autobiography of Malcolm X that deeply influenced E. Ethelbert Miller and many others, Malcolm X reported this:

“I have been utterly speechless and spellbound by the graciousness I see displayed all around me by people of all colors from blue-eyed blondes to black-skinned Africans, but we were all participating in the same ritual, displaying a spirit of unity and brotherhood that my experiences in America had led me to believe never could exist between the white and the non-white.”

Malcolm X continued,

“America needs to understand Islam because this is the one religion that erases from its society the race problem. You may be shocked by these words coming from me, but on this pilgrimage, what I have seen and experienced has forced me to rearrange much of my thought patterns previously held and to toss aside some of my previous conclusions. I have always kept an open mind which is necessary to the flexibility that must go hand in hand with every form of intelligent search for truth.”

MR. MILLER: Malcolm X was able to see African Americans were changing with just a little bit of Islam that they were getting and what he was looking at was, you know, the contribution of Elijah Muhammad, that even though someone would say, well, what Elijah Muhammad is teaching us is not orthodox Islam. It’s sort of a little mixture thing he has here. But still, with that, he was able to do remarkable things in terms of lifting up, you know, African Americans and now, when you look at 2010 in which we really have a better understanding, thanks to Malcolm X and, you know, Muhammad, a better understanding of orthodox Islam, well, that’s what is really growing rapidly within our society as people enter this faith.

I think that what will be interesting to monitor is that African Americans, because we have grown up in the West, that we perhaps will play a key role in the Muslim world in terms of how does one balance one’s faith and Westernization. I think that’s going to be really key. And to see in our country right now many African American Imans, African Americans who are head of Islamic communities. Hopefully, what we will also begin to see are African American Islam scholars who can now sit down and define, you know, various terms and things of that sort and really bring this religion into the 21st century.

TIPPETT: It is really interesting to think about it that way. It also surprises me that Louis Farrakhan still gets all the attention from media and what he represents at this point is such a small sliver of African American Islam which, as you say, has become mainstream.

MR. MILLER: Well, a small sliver, but, you know, we have to look at the contributions that people have made. And even when someone polarizes a community, keep in mind that polarization is sometimes very important in terms of the movement forward, in terms of our lives.

TIPPETT: Do you have the poem “Salat” with you? Do you have that?

MR. MILLER: Yes.

TIPPETT: I had your poems and I was marking and turning pages and I didn’t bring them with me, so that one I remember the title [laughter].

MR. MILLER: That’s why we’re going to get you a Kindle [laughter].

TIPPETT: Yeah, exactly.

MR. MILLER: This is “Salat.”

poetry is prayer

light dancing inside words

five times a day

I try to write

step by step

I move towards the mihrab

I prepare to recite what is in my heart

I recite your name

It is interesting how this poem, for example, I remember someone from Jordan contacted me and they liked the poem. The same way in one of my books, How We Sleep In The Nights We Don’t Make Love, I have a number of poems in which I created a character by the name of Omar.

TIPPETT: Yes.

MR. MILLER: I created Omar because of the changing demographics. You know, you walk into a school and there are more young Muslim kids who are there. And it’s always good when a kid comes up to me especially like in elementary school, “My name is Omar.” All of a sudden, you know, he’s visible and he’s proud. I found that, in those poems, I was using humor to serve as a bridge in terms of bringing people together and using these poems in such a way that, if I go into a classroom, a teacher can follow up my reading in terms of raising questions.

You know, how many of you may have Muslim friends, you know anything about Ramadan, you know, Salat? That’s where the beginning of understanding takes place. I look at myself arriving on the campus of Howard University in 1968 and I had no knowledge of Islam in terms of the number of people in the world who are Muslims. In 2010, we just can’t have that.

TIPPETT: There’s also a very important, I would say, Buddhist note that recurs, that runs all the way through your writing and your poetry. You run sort of a little essay about Langston Hughes’ Buddhist smile [laughter].

MR. MILLER: Yeah. And, you know, what happens. Even today, if you play some tapes of Langston reading, you know, Langston is like a very gentle spirit with a little laugh and the smile. I always say that because, you know, you see that with Langston and then, on the other part, you take someone like Carter G. Woodson noted for starting Negro History Week which is now Black History Month.

Carter G. Woodson like never smiled, you know, like Black History is serious business, serious business. So I take Langston’s smile which, to me, is something which I identify in terms with the poetic experience. I think that there should be people that you should know they’re poets by their behavior, you know. They should be these types of individuals.

You know, I laugh a lot. I’m like a little laughing Buddha, I guess, a Buddha bird or somebody I could be called. I mean, if you’re not living a life that way, I think in this sense you’re missing the essence of life, so that’s the thing where, you know, you gravitate to these religions hopefully that is not simply about rituals, but you’re infusing with a certain sense of being in terms of getting you through this life, and that’s what I think it’s about.

TIPPETT: You know, again, this is all really wonderful to think about in and of itself, but also in the context of the African American experience after the 1960s and 70s because, again, with the election of Barack Obama and through the campaign, African American religiosity was a theme. You know, these Buddhists and Islamic strains that are part of your formation and a part of many peoples’ formation I think gets lost in the larger America imagination about African American spirituality.

MR. MILLER: Well, this is why, you know, what’s very interesting is that, when you begin to look at the greater dialog around religion — and I think religion will be the major issue of this century, not race — what you see is that African Americans are — we represent all these different faiths and that’s extremely important. You know, you go somewhere and you’re not surprised that someone is a Buddhist, you’re not surprised that someone is a Muslim. That gets away from the stereotype that we have that we think that everyone’s Christian.

So this is going to be part of an ongoing dialog, you know, within our community and we haven’t faced it. I’m waiting to see, to have these sort of real serious dialogs between African Americans who are Christian and African Americans who are Muslim because, you know, we haven’t really had that dialog. This is what I feel sometime, you know, African Americans can play a key role like, for example, in terms of the Middle East or in areas where you know what it means to be an outsider, you know what it means to be oppressed, but you also know in terms of, you know, how to move beyond that.

So this is what people, I think, around the world look at or used to look at when they would look at jazz or blues. They would see this universal sound. They would say, okay, I see the hurt, the pain, but I also see the joy and hear the joy and the celebration. You know, teach me to play that music.

TIPPETT: The novelist, Charles Johnson, who he mentioned has written powerfully about the intrinsic kinship in his life between African American identity and Buddhist practice. He first began a meditation practice when he was 14.

In a book called Turning the Wheel: Essays on Buddhism and Writing, he writes that “the historic devotion to freedom by black American leaders prepared him for embracing the Buddhist dharma as the most revolutionary and civilized of possible human choices as the logical extension of King’s dream of the beloved community and Dubois’ vision of what the world could be if it was really a beautiful world.”

Charles Johnson continues,

“Were it not for the Buddha dharma, I’m convinced that as a black American and an artist, I would not have been able to successfully negotiate my last half century of life in this country or at least not with a high level of creative productivity, working in a spirit of Meta toward all sentient beings and selfless service to others which, in my teens, were ideals I decided I valued more than anything else. The obstacles, traps and racial minefields faced by black men in a society that has long demonized them are well-documented. For me, Buddhism has always been a refuge as it was intended to be, a place to continually refresh my spirit, stay centered and at peace which enabled me to work joyfully and without attachment even in the midst of turmoil swirling around me on all sides.”

We’ve put a longer passage from this piece of Charles Johnson’s writing on our Web site and we found ourselves collecting a rich compendium of other readings and materials that we couldn’t use in this program. The verse of Langston Hughes read in his own voice, a video of President Obama’s first press conference that E. Ethelbert Miller will talk about in the second half of this show, also photos of Malcolm X with Martin Luther King, Jr., music from John Coltrane and Miles Davis.

You can find all these resources and more on our Web site, speakingoffaith.org. And in addition to E. Ethelbert Miller poem, Salat, which you heard recited earlier, he also read several other poems during our conversation. He chose a few with far-reaching themes and titles from Buddha Weeping in Winter to I Am The Land, a poem in memory of Oscar Romero. Text versions of these poems and MP3s of his readings are available for download on our Web site or by subscribing to our podcast. Again, all of that at speakingoffaith.org.

After a short break, more of E. Ethelbert Miller’s sense of the African American place in the global present and future, also why baseball is the best analogy for all of these things in the end. I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us. Speaking of Faith comes to you from American Public Media.

[Announcements]

TIPPETT: Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “Black & Universal,” meeting E. Ethelbert Miller. He is a poet, a self-described literary activist and director of the Afro-American Studies Resource Center at Howard University. We’re exploring his playful and challenging take on the trajectory of Black History and culture of the last half century.

He first found his voice through the Black Arts Movement which followed the themes of Black Power through literature and art. It only lasted formally for about a decade after the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, but it was part of a larger world of art and especially music that nourished the emerging black consciousness and sustained it with a fusion of the artistic, the political and the spiritual. John Coltrane’s 1964 recording, A Love Supreme, was experienced by many as an iconic rendering of that fusion, a musical resolution of pain in an active spiritual devotion.

TIPPETT: You named the Afro-American Studies Department magazine that you once edited after John Coltrane’s album, Transition, and you wrote this:

“Trane was going where I wanted to go. The spiritual development in his last years, the pursuit of music as a way of talking to the Lord as in Dear Lord. John Coltrane was either our heart or our soul, the goodness we needed to survive the madness of winter in America. I could listen to A Love Supreme all night long.”

The question I wanted to ask you is what sustains and nourishes your children now the way this music sustained and fed you? Is there a John Coltrane for their generation?

MR. MILLER: You want to say, for example — and this is a thing where we just saw, you know, the death of Michael Jackson. What happens is that because of how our technology and how we’re packaging things, it’s going to be interesting how someone will emerge. I mean, I look at American Idol and I laugh at it because what I feel American Idol does is reward mediocrity. You’re never going to hear a really great voice that abides in the whole thing that anybody could win, and that’s good for ratings and sales, but not for music lovers.

But what happens is that the way things are now, you know, we have to look in terms of where that person who’s taking something to another level is coming from. That’s why my second memoir — you know, I stumble upon Ichiro, you know, Ichiro of the Seattle Mariners, because I saw here was somebody almost in the age of steroid baseball and all this other stuff perfecting the game, perfecting the game on almost every aspect.

When you begin to see that, you know, like somebody who looks at Peyton Manning, that somebody is really taking what they do to a level where you thought no one could do that. We have to ask ourselves where does that occur across the board? So if, for example, we look at Barack Obama, we can disagree with his policies, but we know the guy looks good as president [laughter]. I mean, the guy looks good. If you had to sell the American boy, you know, even now, when you got to do the little posters and you hate the policy, but the guy looks good.

TIPPETT: You’ve made this connection between — you said that Barack Obama has made a connection in the American imagination between blackness and beauty, that Barack and Michelle Obama have done that.

MR. MILLER: Exactly. In fact, that’s what I tell people. Michelle Obama’s impact will probably be great in any legislation that Barack Obama will pass, and why? Because she shifts the paradigm in terms of beauty. When I saw a year ago, a number of young white girls when they were asked who the most beautiful woman in the world was, they said Michelle Obama.

I said, “Oh, wow. This really frees up the little black girl who was in kindergarten being laughed at in terms of her color.” If now a girl with blonde hair — you know, this like sends everybody to the tanning room, you know, because what happened, the standard of beauty has shifted and that becomes very, very important in terms of a race feeling good and comfortable about itself.

This is why people want Obama to be successful because it is on the world stage and this is why, when you look at the inauguration, you look at the end of the election night, you see people crying. You know, you see Jesse Jackson. I always tell folks, follow the tracks of Jesse’s tears, you know. What happens is that there’s so much that you never thought could happen and it’s been kicked over. The next thing you have to ask is what’s coming after this? And what happened? Even Obama will shift it back to us as people that, okay, this is what we have to do. I can’t do this. I’m just President of the United States.

TIPPETT: Like E. Ethelbert Miller, Lucille Clifton began her life as a poet in the last 1960s in the circles around the Black Arts Movement and, like him, her poetry moved out from there to issues of gender and the broader human condition. Lucille Clifton won the National Book Award in 1999. Here she is reading her poem, “Won’t You Celebrate With Me?”

LUCILLE CLIFTON:won’t you celebrate with me what i have shaped into a kind of life? i had no model. born in babylon both nonwhite and woman what did i see to be except myself? i made it up here on this bridge between starshine and clay, my one hand holding tight my other hand; come celebrate with me that everyday something has tried to kill me and has failed

TIPPETT: Your fusion of art and politics took you out from the black experience, as you’ve written, to Latin America, to women writers. But, you know, that also makes me think — I get back to something you said a minute ago about the way the Black experience, especially in your lifetime, distinctly enables you or empowers you to make a connection with other people around the world.

MR. MILLER: Well, that’s how I was raised, you know. It took me going off to college, you know, coming to Washington, D.C., actually coming south, to understand that my father was born in Panama, that the rest of my family was from Barbados. Then I was beginning to understand that, okay? Then when I look at my beginnings, when I look at my elementary school, PS 39, the same elementary school that Colin Powell went to actually.

TIPPETT: Oh, really?

MR. MILLER: Right. When I looked at that school in the South Bronx, I looked at my classes, the level of diversity was unbelievable. You know, we had many people who were Polish, we had many people who were Chinese, you know, African American. It was such like a U.N. In fact, one of the major transformations I underwent was when I went from PS 39 which was this fantastic sort of U.N. elementary school to Paul L. Dunbar Junior High School 120 which was all African American. I came home crying, you know. I had never been in a school in terns of all black kids running around and things of that sort, you know.

I was really isolated and traumatized actually because I came from a place in which, you know, many of my friends were actually not African American. They were Puerto Rican, they were Chinese, you know. So those individuals, those friendships, I think molded me and so as I got older and living in parts of D.C., you know, like Adams Morgan and Mt. Pleasant, I immediately gravitated to people from Nicaragua, Guatemala, you know, because that was what I was accustomed to.

TIPPETT: You wrote somewhere that what is Black History but a series of coincidences that run parallel to everything in the universe.

MR. MILLER: Right. You know, if we look at what happens to the black experience, we seem like, you know, as writers and artists, this is why you have certain African American artists. They try to move you on a label. Oh, don’t label me as an African American artist. I’m an artist. We get stuck in that. You know, my thing is that, if you’re black, you’re universal. That’s why, you know, I said we’re all black poets at night. You turn the lights out and everybody’s black [laughter]. Once again, this is how I approach blackness. That is, it’s celebratory, you know, that it’s something that we embrace. It is not a burden, you see. It’s something that I don’t want to move away from. I want to move closer to.

In the process of that, it will find me at times at odds with people who might define themselves as Black Nationalists because I feel that, after you go through this whole thing of who you know who you are, which is wonderful, if you want to trace yourself back to kings or the pyramids or whatever, that’s nice, but then it’s very important that you turn away from this narcissistic mirror and you begin to look out the window and you begin to realize there are other people out there with different histories, different mythologies, and that your job now is to enter out into the world.

Your history, your ideas, is a gift and you’re also in a position where you receive the gift of other peoples’ culture, and that’s the exchange, that’s the exchange. That’s the thing that we’re beginning to see now. African Americans are just moving around the world. They’re realizing, okay, you know, they’re there and they belong. I look at how trapped I was the first time I went to Norway, you know.

TIPPETT: How trapped? What do you mean?

MR. MILLER: Yeah. Trapped in terms of people say, oh, man, you’re going out there. You’re not going to see, you know, the country’s all white [laughter]. I get off the plane and, you know, you’re going through Customs and the first person who welcomes me to Norway is a black woman [laughter]. It’s a black woman, you know?

As I walked around Oslo, it’s a very multi-cultural city, but what happened was I was walking around thinking everybody was going to be a Viking, you know. Then the other thing which I’ve always looked at is that, if I’m a young white kid, I can go anywhere and no one says, oh, what are you doing here? But if you’re a black person, you show up in like Wyoming, it’s like what are you doing? Well, I’m hiking. What are you doing?

All of a sudden, we have to explain our presence, you see. That is something I feel is a problem, that, you know, we are still locked in. Or as black people, we don’t want to go certain places because, you know, we don’t want to be the only black person there. How will we be perceived? That’s why sometimes those of us who are very cautious, you know, we go somewhere, oh, there’s another black person, okay, all right, you know. No matter how old you get, you’re still dealing with these little moments in which you’re not certain about something.

One of the most beautiful moments of the Obama administration was his first press. I mean, where he’d walk into the room and meet the press and they all rise up and he jumps a little second. He’s like, whoa, I’m president [laughter]. Like all of a sudden, it caught him. You’re like, whoa, you’re president, you know. Those are very small things that, you know, you realize, okay, he’s still thinking this and what about the rest of us who haven’t had these experiences?

This is the thing I feel that, at the end of the day, if we are celebrating who we are as black people, we have to realize that it is healthy to be black, it’s beautiful to be black and it’s one of many colors out here and we have to make sure that we don’t abuse it, that we’re always polishing ourselves not because we want to try and impress somebody, but the fact that this is what we do. This is the tradition that’s been passed on. This is our legacy, you know.

I tell people, if you’re not going to work as hard as the boys of Garvy — you know, who are these people who have laptops? I mean, they were productive. Or the work habits of Booker T. Washington? That’s your tradition. See, I remember Wynton Marsalis saying, you know, I dress up a certain way because I respect the music.

TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, “Black & Universal.” We’re exploring E. Ethelbert Miller’s experiential and literary lens on Black history in the last half century. In 2009, he published his second memoir which he called a riff on middle age, marriage, fatherhood and failure entitled The Fifth Inning.

He writes:

“In baseball, the fifth inning can represent a complete game. The structure of this book consists of balls and strikes. Balls and strikes can also stand for BS. How much is thrown at a person by the time they reach 50? When BS becomes just B, it might represent not balls, but the blues, the blues seen as departure and loss. The B also stands for blackness, perhaps the essence of the blues.”

So, you know, when you look at your children and their friends, how did they make you think and feel about the up and coming generation?

MR. MILLER: Well, you know, I felt there were things in both my son and my daughter’s life that I think helped them become who they were. I looked at my daughter. I had her in a program called, Operation Understanding, which is a wonderful organization that brings blacks and Jewish young people together and they learn from each other. That has been a really unique experience for her that she was able to years later always draw back on, you know, that sort of friendship.

I looked at my son in terms of, you know, when you go through sports and you’re really excelling and you see some of your friends, you know, making it to the NBA, what happens you begin to understand exactly how good you are, you know.

You understand what it takes to win and you understand who you are off the court. That’s the thing where we say we use sports in such a way to bring out the character in a young person. You know, we use the sports in such a way to give that person the discipline and the thing that there are rewards, that, okay, you did such and such and that’s why you have a trophy.

TIPPETT: You know, we’ve touched on so many places. I wonder if there’s any place we haven’t gone, something that you’d really like to talk about. Maybe something that’s new that you’ve been thinking about.

MR. MILLER: Well, the thing that I feel that I sort of try to approach in my last book, The Fifth Inning, was to look at issues of depression and how that I think is very important in terms of working your way through that so that you can celebrate life. I have friends who have problems getting out of bed, you know. I’ve had a number of friends who have, you know, committed suicide. So I’m very concerned about that in terms of, you know, what the symptoms are, just making sure that, if you’re ever in a situation, you might be able to give advice that can be lifesaving.

TIPPETT: I think part of your integrity as a person and as a writer that other people have noted in you is that you do talk about the breadth of your experience and it’s not all light. There’s darkness, there’s depression.

MR. MILLER: Right, and that’s because it’s back to baseball. You know, when you’re successful, you just get three hits every ten times you get up [laughter].

TIPPETT: [Laughter] One of the last lines of The Fifth Inning is “All I know is baseball.” Is that right?

MR. MILLER: All I know is baseball, right. You know, basically you could say that’s almost like a Buddhist thing where, you know, what do you know? Sometimes it gets down to something very simple, you know, where you travel the entire world and the only thing you really know is your home. I mean, that’s it. The only thing you know is your heart. Basically, why I like the sports, especially baseball, you know, one, it’s very exact and you never know what’s going to happen until the last out. As I tell people, it’s one of the games that begins and ends at home. It represents that journey, you know. Not too many games are like that.

TIPPETT: You wrote naming ourselves is what many of us did in the late 60s. We took African names and Muslim names and names we created like musical improvisations. Naming is also so resonant for me. You know, it is the original creative act.

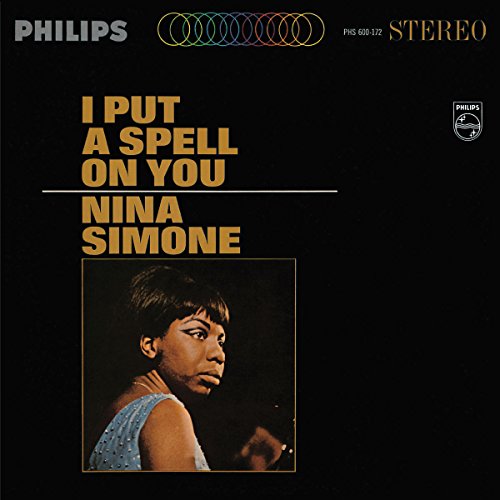

MR. MILLER: And it was the most difficult job I’ve ever had was naming my children. That was really — you know, what am I going to name my child? What’s the nickname going to be? Are they going to grow out of their name or grow into their name? I look at my daughter — her name is Jasmine-Simone and that seems to work. She’s still Jasmine. She hasn’t grown into that Jasmine Simone. I keep pushing that Simone because that’s supposed to be that sort of Nina Simone, you know, backbone.

Then my son surprised me because — his name is Nyere-Gibran. I took Julius Nyerere’s name and merged it with the Lebanese poet, Khalil Gibran. He had never used Gibran, but now he sent me a little text and he was like “Gibran.” I said, “What’s this?” You know, “Mr. G.”

TIPPETT: He’s doing what you did.

MR. MILLER: Right.

TIPPETT: And choosing their names.

MR. MILLER: Choosing their name and something that you look up and it may not resonate right now or they might abbreviate it, you know, but that’s very important in terms of, especially in this world, branding. That’s a thing where I might begin another book because, upon discovering that my last name is probably not Miller, that’s another story. My sister says, do you know this could be our last name? It’s not Miller? So the naming process is key and that has been the case with many immigrants coming into this country, that they assume another name. That was probably the situation in terms of my father. So that’s another book to write about.

TIPPETT: Okay. Well, it’s been said that your memoirs are written a bit like jazz riffs and I think this conversation has been a bit like one, but it’s great. It was a lot of fun.

MR. MILLER: All right. Stay well.

TIPPETT: E. Ethelbert Miller is director of the Afro-American Studies Resource Center at Howard University. His books of poetry include How We Sleep On The Nights We Don’t Make Love. His memoirs are Fathering Words and The Fifth Inning. We’ll end with some of the closing lines of a speech he once gave title My Language, My Imagination: The Politics of Poetry.

He said this:

“What I have learned from the Black Arts Movement is that all things eventually point towards truth and justice. Years ago, the Black Arts Movement gave me the power to see the beauty of my blackness. Today I must not be blinded by race, but instead my political imagination must be open to understand the differences I have with others. I must be strong enough to construct cultural bridges. What is poetry but that which we feel most deeply? What is poetry but that which tells our soul to sing?”

You can find the full text of this beautiful speech by E. Ethelbert Miller as well as Lucille Clifton’s poem, “Won’t You Celebrate With Me?” on our Web site. While at speakingoffaith.org, take advantage of all the extra audio we offer, including MP3s of this program, my unedited interview with E. Ethelbert Miller and the SOF Playlist which allows you to stream all the tracks of music you heard in this program, songs by John Coltrane, Nina Simone, Miles Davis and Wynton Marsalis. Also, some of our richest ideas and most engaging conversations are taking root online through our blog, Pertinent Posts from the On Being Blog, and on our Facebook Fan Page, even Twitter.

We recently streamed live video of my public conversation with the Evolution of God author, Robert Wright. We’ll be turning that into a radio program in a few weeks. He’s an interesting voice charting a new way forward in our public understanding of the interplay between science and religion, faith and reason.

That is one of my favorite topics and I’m excited to have a new book coming out in paperback this month called Einstein’s God: Conversations About Science and the Human Spirit. Learn more about all of this and find ways to join others in meaningful discussion about every aspect of life at speakingoffaith.org.

Speaking of Faith is produced by Colleen Scheck, Chris Heagle, Nancy Rosenbaum and Shubha Bala. Our producer and editor of all things online is Trent Gilliss with Andrew Dayton. Special thanks this week to Desiree Cooper, The Poetry Foundation and Copper Canyon Press. Kate Moos is the managing producer of Speaking of Faith, and I’m Krista Tippett.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.