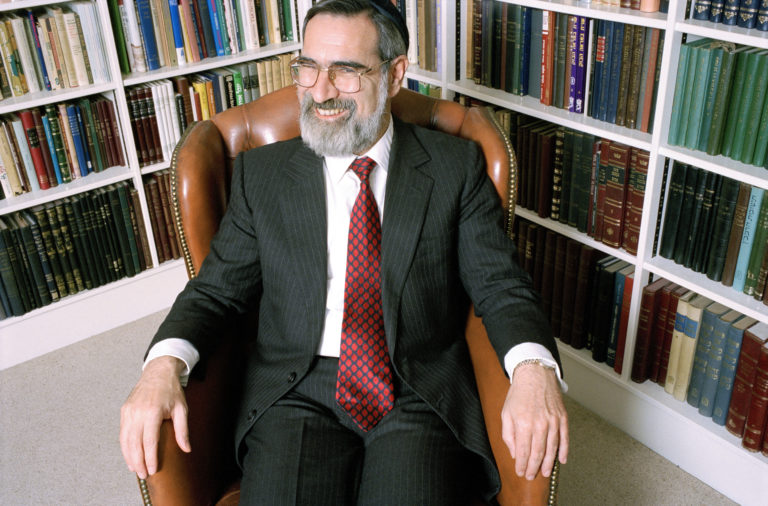

Jonathan Sacks

Enriched by Difference

“That’s how we are as a people. It’s the authentic, the unique, the different that makes us feel enriched when we encounter it.” Rabbi and philosopher Jonathan Sacks on difference as expansive and unifying, rather than a force for division.

Image by Donald Maclellan/Getty Images/Getty, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Jonathan Sacks was Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth for 22 years. He taught and spoke all over the world, with appointments at King’s College London and at New York University and Yeshiva University in the U.S. His many books include The Dignity of Difference: How to Avoid the Clash of Civilizations, The Great Partnership: Science, Religion, and the Search for Meaning, and most recently, Morality: Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times.

Transcript

Krista Tippett, Host: Any conviction worth its salt has chosen to cohabit with a piece of mystery. All of our traditions insist on a reverence for what we do not know now and cannot tie up with explanation in this lifetime. This is an invitation to bring the particularities and passions of our identities into common life, while honoring the essential mystery and dignity of the other — and to do so not as an adjunct to faithfulness, but as an article of it.

Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, who held the august title of Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth — otherwise known as chief rabbi of the UK — for over 20 years, until 2013, is one of our most eloquent thinkers on the multitudinous and redemptive both/ands of the religious present. He finds in Jewish tradition, and in the religious enterprise as a whole, a profound well of tools to take on “the dignity of difference” and keep vibrant identities intact, across boundaries of faith, science, and culture.

Ms. Tippett: I remember a statement of a very intelligent, excellent American journalist after September 11, 2001 — that what those events demonstrated was that in order for the three monotheistic religions in particular to survive and be constructive members of society in the twenty-first century, they would have to relinquish their exclusive truth claims. That, I think, made a lot of sense to many people. The case you make also aims towards the traditions being constructive parts of the twenty-first century, but you take it in a different direction. So let’s talk about how it is possible in your imagination to retain the essence, the truth claims, of Judaism and also, as you say, honor the dignity of difference, understand one’s self to be enlarged rather than threatened by religious others.

Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks: I use metaphors. Each one may be helpful to some and not to others. One way is just to think, for instance, of biodiversity. The extraordinary thing we now know, thanks to Crick and Watson’s discovery of DNA and the decoding of the human and other genomes, is that all life, everything, all the three million species of life and plant life — all have the same source. We all come from a single source. Everything that lives has its genetic code written in the same alphabet. Unity creates diversity. So don’t think of one God, one truth, one way. Think of one God creating this extraordinary number of ways, the 6,800 languages that are actually spoken. Don’t think there’s only one language within which we can speak to God.

The Bible is saying to us the whole time: Don’t think that God is as simple as you are. He’s in places you would never expect him to be. And you know, we lose a bit of that in English translation. When Moses at the burning bush says to God, “Who are you?” God says to him three words: “Hayah asher hayah.” Those words are mistranslated in English as “I am that which I am.” But in Hebrew, it means “I will be who or how or where I will be,” meaning, Don’t think you can predict me. I am a God who is going to surprise you. One of the ways God surprises us is by letting a Jew or a Christian discover the trace of God’s presence in a Buddhist monk, or a Sikh tradition of hospitality, or the graciousness of Hindu life. Don’t think we can confine God into our categories. God is bigger than religion.

Ms. Tippett :Although at the same time as you say that God is bigger than religion — and I think this is an “and” for you and not a “but” — there is also a special relationship that is evidenced in those texts and a covenant that is particular to the Jewish people. So even as you honor the dignity of difference in the contemporary world, you are upholding the dignity of particularity.

Rabbi Sacks: By being what only I can be, I give humanity what only I can give. It is my uniqueness that allows me to contribute something unique to the universal heritage of humankind. I sum up the Jewish imperative, very simply — and it has been like this since the days of Abraham: to be true to your faith and a blessing to others regardless of their faith. That’s the big paradox when you really reach the very depth of particularity.

I don’t know why it is. An Isaiah comes along and he delivers his prophecies and they’re so particular to that faith, that place, that time. Yet I call Isaiah the poet laureate of hope. At the height of Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, at the very height of it, there he is quoting verbatim two lines from Isaiah, Chapter 40. I doubt whether Isaiah, 27 centuries ago in the Middle East, could envisage that one day a black civil rights activist would be moved by his words. But it’s the particularity of Isaiah that spoke to a Martin Luther King. That’s how we are as a people. I don’t know why it is, how it is, but it’s the authentic, the unique, the different that makes us feel enriched when we encounter it. And a bland, plastic, synthetic, universal can’t-tell-one-brand-of-coffee-from-another-brand-of-coffee by contrast makes life flat, uninteresting, and essentially uncreative.

Ms. Tippett :There’s a line of yours — and it might please you, I think, that I first heard it quoted by a young Muslim interfaith leader, Eboo Patel. You said: “Religion is not what the enlightenment thought it would become — mute, marginal, and mild. It is fire and, like fire, it warms, but it also burns and we are the guardians of the flame.” What do you see when you look at the world, in terms of seeds of a deeper moral and spiritual imagination emanating from your tradition and other traditions? Where are you finding hope?

Rabbi Sacks: I think God is setting us a big challenge, a really big challenge. We are living so close to difference with such powers of destruction that he’s really giving us very little choice. To quote that great line from W. H. Auden, “We must love one another or die.” That is, I think, where we are at the beginning of the 21st century. And since we really can love one another, I have a great deal of hope.