Esteban Rodríguez

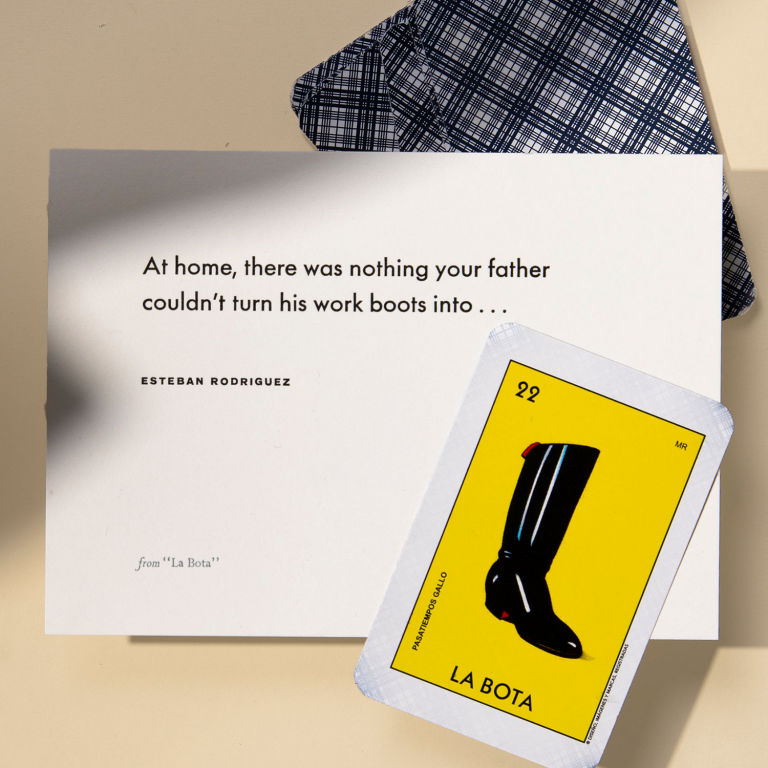

22 La Bota

A poet considers his father, and, particularly, his father’s boots. These boots could be a hammer, a prop, a weapon. But Esteban Rodríguez also remembers how his father — a sleepwalker — would walk outside at night in his underwear, wielding his boots, slapping them against each other in a kind of protective ritual. What spirits was his father protecting them from? What was he asserting about land and place, by standing guard, even in his dreams?

Letterpress art by Myrna Keliher.

Image by Lucero Torres, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Esteban Rodríguez is the author of five poetry collections, most recently, The Valley. His debut essay collection Before the Earth Devours Us will be published by Split/Lip Press in late 2021. He is the Interviews Editor for the EcoTheo Review, an Assistant Poetry Editor for AGNI, and a regular reviews contributor for Heavy Feather Review. He lives in Austin, Texas.

Transcript

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and for years I had a recurring dream. The dream was always that I was about to walk into a large cave and that I knew that something waited for me in the cave and that I was very frightened. And the whole dream would be building up and building up to getting to that mouth of the cave, going in or waiting or not. And then I’d wake up. And something happened to me, when I began to go into that cave, in my poems, in my imagination, even. Something new occurred.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

“22 La bota” by Esteban Rodríguez:

“At home, there was nothing your father

couldn’t turn his work boots into—

a hammer for loose nails, a prop to even

stubborn tables and chairs, a weapon

to end the lives of anonymous insects.

And there were nights when he would sleepwalk,

and out in the yard with nothing but underwear

on, he’d smack together the bottoms of his boots,

as if there were spirits he had to ward off,

as if his past had taken on some once human form,

and to remind him that no one is ever free

of sin, made it its duty to stalk him at home.

And though it lasted no more than a few minutes,

and your mother would wake him up,

bring him back in, you figured that the boots

had done their job, that the reason he never used

sticks, pots or pans, or yelled at the top

of his lungs was because he wanted the spirit

to know exactly who he was,

that he had every right to be at peace

on whatever ground he walked.”

[music: “Memoriam” by Gautam Srikishan]

This poem, “La bota,” is the 22nd poem in a poetry sequence titled “Lotería.” And lotería is a traditional game of chance, popular in Mexico and in Mexican-American cultures. It’s kind of like bingo, but uses images on a deck of cards instead of numbered ping-pong balls. And each poem in this sequence of poems revolves around one of the 54 cards. So this poem, “La bota,” is number 22 in the sequence of those lottery cards from lotería. For instance, number one is “El gallo,” the rooster, and number two is “El diablito,” the little devil. And so there’s something that really ties in with a game of entertainment and a game of chance and a game of lottery and betting, as well as a game of culture and a game of place, in this poem. And this poem is so rooted in the homestead of a family. And the homestead of the family is being located within a broader culture.

[music: “Into the Earth” by Gautam Srikishan]

So much of the energy of this poem is taken up in the observation of a strange thing, someone sleepwalking. And even though it’s not unusual — lots of families will have somebody that sleepwalks for a period of time or for a long time, in that family. But the sleepwalking that we’re watching here brings us into the mystery of a person. What are they living through? We all know that our dreams can be a strange world, but somehow, sleepwalking in a dream puts a certain kind of embodiment into that. And so what we are looking at is a strange experience that can’t be fully explained, where there is another world underneath the world of this family homestead. There is another personality, maybe, or a presence of old anxieties in the father character, in this poem.

And we hear from the start of the poem that he’s able to use his work boots for anything, straightening out a table or getting rid of an insect. He seems like a handy man; he seems like an efficient man. He seems like somebody who likes to turn their hands to all kinds of things — in control, in a certain sense; a doer, a fixer. But here he is, on the one hand fixing his life from the accusations from these ghosts, these spirits that seem to be coming, but on the other hand doing that in a dream state. And it is his strangeness that’s present.

And all of this is narrated through the observation of his son. And I always find myself wondering, when I read this poem, how old was the son in this poem? Esteban Rodríguez is the poet, yes, but I don’t know what kind of age he was when this was being observed by him. I wonder, was he young? Was it recently? Who knows? But there’s a way within he, seeing his father in a new light too, not just a father who has work boots, and also not just a mother who’s able to guide the father in, waking him gently and bringing him back, but he’s seeing parents in these different roles that don’t have anything to do with him, in a certain sense; that have everything to do with the pasts when he wasn’t alive, and the pasts are entirely present there.

[music: “Into the Earth” by Gautam Srikishan]

Another way to think about what’s happening in this poem is to ask the question, where do we go in our dreams? — with emphasis on “where,” not only on “dreams.” This poem begins with the words “At home,” and it all takes place in a homestead, and we can hear the sounds of somebody hammering at home, or wobbly tables. And then, suddenly, we’re in the yard. And the place of the poem, too, becomes mysterious, because it isn’t the present place. It’s the past place, and the father is haunted. You’re not “free from sin.”

But even though all of these voices are coming at him, he stands still in place and slaps those boots as if to say, “I have every right to be at peace on whatever ground I walk on.” And why that? What is the element of ground here, and place, that comes up in the very last line? The first line is “At home,” the very last line is about ground and being at peace there. What is this poem telling us about the experience of needing to defend your place? Who would have a boot on the right of this family’s capacity to live where they live, to stay where they stay, to work where they work, to speak the language they speak? In what way is the boot being used as a threat, and how is the father standing firm in place, naked almost, slapping boots together as if to ward off the boot that would want to kick them out of a place?

[music: “Every Place We’ve Been” by Gautam Srikishan]

This poem uses a certain kind of objectification to focus our attention on the boots. And the boots are used for all kinds of purposes. They’re work boots, so first of all, they’re used for work. But then they’re also a hammer or a prop or some kind of a way to get rid of insects or to squash insects. But then they’re a weapon against unseen things, too, a kind of a divination tool. And there’s something here about realizing that things as concrete as a pair of work boots don’t just mean one thing. They can mean the dignity of having a job. They can mean something about being able to walk in your own land. They can mean something about having a right to be where you are, a right to have a job, a right to the pride of your own home, and also kind of an indication of having a role, of being respected. And the drama of this poem is seeing that even in the father’s dreams, he still has to assert his own sense of respect, even against the spirits of the past that are implying that there are sins that they would wish to accuse him of, or displacements that they would wish to land him on. And he is exorcising himself from all of these forces around him, with these boots. They’re working, even in his dreams.

[music: “Sad Story” by Blue Dot Sessions]

So this poem has a variety of questions that it asks. We’re observing this experience of a father outside, in his underwear, slapping his boots together to ward off whatever it is that’s happening in his dream. But then the poem keeps on saying, “as if … as if …” The poem doesn’t know what’s really happening, and so the poem is really asking the question about what it’s like to ask questions about somebody that you think you know but has aspects about themself that are always going to be mysterious — to themselves, even, never mind the rest of their family.

And so this poem is finding its own place by asking questions about all the possible things that could be happening. This is a brilliant reminder from this poem, and an invitation almost, for us to think about what are the other lives that people around us — people we live with, people we work with, people we’re over-used to, in terms of sharing space — what are the other lives that they’re always carrying with them? What are the conversations they have when they think nobody’s watching, or nobody’s listening? Where do they go to in their dreams? What are the accusations or consolations or imaginations that come to them when they’re asleep, or even when they’re daydreaming? Who are they, and who are we around each other? This poem takes something familiar, a small family unit, and introduces strangeness to it and doesn’t give us an answer. It just gives us a whole load of questions.

[music: “Toothless Slope” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Sometimes, when you read a poem, it can be really worthwhile to just read the lines separately and to stop at the end of a line, even if there isn’t a full stop or a period at the end of that line, to just see, what would it be like if I took that line — even if it’s only half a sentence — by itself, with its own integrity? So you could take the line, for instance, “And there were nights when he would sleepwalk,” or the line “to remind him that no one is ever free.” The poem goes on to say “of sin,” but I like to look at the line just there by itself, “to remind him that no one is ever free.” This poem knows that the past has all kinds of accusations against the freedom of the present.

And I keep on returning to the second-last line, “that he had every right to be at peace.” This is somebody watching somebody watching somebody who has to fight for their peace. And there is a pausing that we’re brought into, again asking, who would accuse, from the past or the present, this father character in the poem, that he shouldn’t be at peace? Who would say to him, “You don’t belong where you are, and you don’t own the peace you have?” What was he warding off? And the poem again, just in that second-last line, “that he had every right to be at peace,” reminds us of the ways within which poetry is making a strong declaration about the dignity of the human person.

[music: “Memoriam” by Gautam Srikishan]

“22 La bota” by Esteban Rodríguez:

“At home, there was nothing your father

couldn’t turn his work boots into—

a hammer for loose nails, a prop to even

stubborn tables and chairs, a weapon

to end the lives of anonymous insects.

And there were nights when he would sleepwalk,

and out in the yard with nothing but underwear

on, he’d smack together the bottoms of his boots,

as if there were spirits he had to ward off,

as if his past had taken on some once human form,

and to remind him that no one is ever free

of sin, made it its duty to stalk him at home.

And though it lasted no more than a few minutes,

and your mother would wake him up,

bring him back in, you figured that the boots

had done their job, that the reason he never used

sticks, pots or pans, or yelled at the top

of his lungs was because he wanted the spirit

to know exactly who he was,

that he had every right to be at peace

on whatever ground he walked.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Lily Percy: Thank you to Esteban Rodríguez, who gave us permission to use his poem “22 La bota.” Read it on our website, at onbeing.org.

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Chris Heagle, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, and me, Lily Percy.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions. This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land.

We also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me. Find those wherever you like to listen, or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.