Peter Berger, Seemi Bushra Ghazi, Lindon Eaves, Et Al.

Evolving "Faith"

At the turn of the year, we look at how American culture’s encounter with religious ideas and people has evolved in the past decade — and this radio project with it.

Image by Ezra Comeau-Jeffrey/Unsplash, Public Domain Dedication (CC0).

Guests

Joe Carter was a singer, performer, teacher, and traveling humanitarian. He performed for more than 25 years in opera and musical theater, portrayed Paul Robeson in a one-man musical, and introduced people around the world to the spiritual. He died of leukemia at age 57, on June 26, 2006.

Khalid Kamau grew up in Atlanta but now lives in New York City where he was a financial analyst for a nonprofit.

Desmond Tutu was an Anglican archbishop emeritus of Cape Town, South Africa and recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. He has written numerous books for adults and children — including The Rainbow People of God, No Future without Forgiveness, Made for Goodness, and, together with his good friend the Dalai Lama, The Book of Joy.

Wangari Maathai founded the global Green Belt Movement, which has contributed today to the planting of over 52 million trees. She was the 2004 recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize. Her books include the memoir Unbowed and Replenishing the Earth: Spiritual Values for Healing Ourselves and the World. She’s also one of the 100 heroic women featured in the book Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls. She died in 2011 at the age of 71.

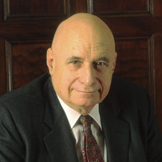

Peter Berger is Director of the Institute on Culture, Religion and World Affairs at Boston University.

Transcript

December 30, 2010

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: The world is changing, and so is the nature of faith in modern life. This radio show was conceived to explore that. And in the process, we too were changed. What began as Speaking of Faith became On Being. This hour, at the end of a momentous decade, we listen anew to voices and ideas that tell the evolving story of meaning and religion in our time — from encountering Islam to new questions 21st-century ecologies and economies are raising about what it means to be human and how we want to live.

From American Public Media, I’m Krista Tippett. Today, on Being, “Evolving ‘Faith.'”

RABBI LAWRENCE KUSHNER: One of the reasons that speaking of faith is such a slippery and a moving target is because we’re trying to talk about the stuff of which we are.

MS. JENNIFER MICHAEL HECHT: If you have a doctrine, a version of rationalism or a version of atheism that makes it so that you have to be worried about using the word mystery, you’ve got yourself too constraining a doctrine.

DR. LINDON EAVES: If you really look at human experience, the truth is that we’re all living a life of experiment in every aspect of our lives.

MR. PARKER PALMER: I understand that to move close to God is to move close to everything that human beings have ever experienced. That, of course, includes a lot of suffering as well as a lot of joy.

MS. KATY PAYNE: If I could ask these animals that I like so much if there’s anything equivalent to what we speak of as being faith, I would love to do that.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, right.

MS. PAYNE: We just don’t know. We just don’t know. [whale sounds]

DR. DAVID HILFIKER: It’s not just that caring for the needy acquaints you with God, but caring for the needy is God. And I experience something like that. It’s something about living this way that is the deepest way that I can imagine to live.

MS. TIPPETT: In the early days of piloting this program, in the early 2000s, it felt essential that “faith” be in its title. Because in American media and political life, we’d handed that word over to a few very strident voices.

They’d burst into a kind of void — where there was no diverse public vocabulary for the part of life we call religious and spiritual.

That had weakened after the 1960s. Great American intellectuals predicted that as the world continued to grow more technologically advanced, more modern in every way, religion would recede to the private sphere. Maybe it would disappear altogether.

But by the time this weekly program started seven years ago, that appraisal was being reversed. I asked the sage Boston sociologist Peter Berger about this in a 2005 show we called “Globalization and the Rise of Religion.”

MS. TIPPETT: I mean, a question I have is did religion recede in the rest of the world or were Americans just not paying attention to it? Or has it sort of been there, bubbling along, and we’re just noticing?

DR. PETER BERGER: Well, I think you have these powerful eruptions which are new, but most of the world has never been secularized. Now, you used a nice phrase before, it was bubbling along all the time.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. What has changed in the last few years or in the last decade, that religion has suddenly burst out onto the surface in this country again? How do you think about what’s happened?

DR. BERGER: Well, if you look at the view of religion, say, of the American Civil Liberties Union, which is basically — I’m satirizing it a bit: Religion should be something that takes place among consenting adults in private, OK? And this view has, at least for a while, strongly influenced the federal courts. Now, that’s not how most Americans think about religion.

Let me step back a moment. Sweden is the most secularized country in Europe, probably in the world. Probably the most religious country in the world is India. The religious situation in the United States could be described as a nation of predominantly “Indians,” in quotation marks, with a cultural elite, which is “Swedish,” in quotation marks.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

Still, for all I could tell my colleagues in broadcasting in 2000 that religion is a force in disparate lives and in the world, September 11, 2001 appeared as bitter evidence. I was in Washington, D.C., that morning, trying to raise my first big grant for this fledgling radio program when the airplanes hit the twin towers and the Pentagon. I drove home across the country knowing we had this one little hour of radio to shed light on some of the agonizing questions that had been raised. Like, ‘what is Islam?’ Five weeks later, we put out a show called “The Spirit of Islam.” Beyond the declarations and actions of terrorists, the U.S. was on a collective crash course to understand the basics of this religion of over 1 billion people around the globe.

[Sound bite of Seemi Ghazi recitation]

And just listen to Seemi Ghazi, a Muslim woman, a reciter of the Qur’an, whom I interviewed for that October 2001 show. Together with other Muslim guests in the years that followed, she began to give us a broad and tethering sense of the intellectual, aesthetic, and spiritual heart of Islam. This is always lost in news that focuses on violent acts.

MS. SEEMI GHAZI: You know, in a time like this, I’ll be asked to speak so many places and, you know, and I’ll have to sort of try to express some of this, but, you know, mostly what people want to hear about is the veil and so …

MS. TIPPETT: Do you wear a veil?

MS. GHAZI: I don’t. I sort of dress very modestly by North American standards, let’s say, and I tend to wear sort of long sleeves and long pants and things like that, but when I recite Qur’an, I’ll often cover my head. Or when I pray, and if I’m in parts of the Muslim world where that’s sort of the more modest alternative, then I generally do.

I mean, well, let me just say not about the veil, but when I have a shawl, you know, when I cover my head, you know, part of what you’re doing is creating a space apart and a space which is sanctified. And in the traditional Muslim world, men cover their head, as well as women. We all cover our head, and there are many kinds of interpretations of that. One is that by having a turban or by having something on your head, you’re emphasizing this kind of vertical principle which links you with the divine.

And another way of understanding it is that, you know, divine splendor is so extraordinary, it’s so great, that this is almost a shelter for us. And another way of thinking of it: as a crown. You know, there’s many ways to think of it, but, you know, I love the feeling of taking my shawl and wrapping it around me before I pray because it does enable me to create another world. And especially as a woman when you’re often trying to attend to, you know, a thousand mundane tasks and get to work or to school or whatever you need to do, that makes a profound difference.

For me, it’s a portable sanctuary. And, you know, no one’s telling me that I have to, so I have the freedom to interpret it that way also and to feel that way about it.

[Sound bite of Seemi Ghazi recitation]

MS. TIPPETT: In those earliest years of this program, as much as we were compelled to cover religion writ large, I also found myself drawn to people who were living with religious questions in unexpected professions. Today, conversations with scientists are at the core of what we do.

And it was a geneticist, Lindon Eaves, who first really started to open my imagination about science and the human spirit in a much more generous interplay than science-religion debates suggest. He has run one of the oldest long-term studies of identical twins — fascinating, important research. And he is at the same time an Anglican priest.

DR. EAVES: If you really look at human experience, the truth is that we’re all living a life of experiment, and I mean in every aspect of our lives. I mean, you know, the — so you can — you can either think of let’s say the creeds of the great traditions, as it were, as telling you what you ought to think, or you can say they are in some sense comparable to the theories of science. They are the best distillations of where we’ve been. But we don’t approach reality treating those models as if they’re the last word. We treat them as operational hypotheses.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, I like to think of the creeds as the outlines of arguments that have been passed down to us, but — but somehow because people are so underinformed about what the arguments were …

DR. EAVES: Yeah. I’ll tell you, the thing that doesn’t feature much in a lot of theological discourse, of course, is the role of mysticism. Now, I was going to be careful about that because when you use the word “mystic,” it has all sorts of weird connotations as well. But there’s a wonderful passage in one of Einstein’s essays where he asks the question, ‘What is it,’ you think he says, ‘that motivates the scientist to work the long hours of the night trying to find the answer to the complex puzzles of life, you know, when most people have long ago given up?’ And of course, that’s a profoundly — profoundly spiritual question. And I’ll tell you, there is nobody who comes close to articulating the ultimately uncertain nature of our experience as John of the Cross. You know, I mean, when he talks about setting out on the dark night with only the fire of longing in his heart kind of thing, that’s something that is very close to the spirituality of the scientist.

MS. TIPPETT: We called that show with Lindon Eaves, “Science and Being.” I’m Krista Tippett. Today on Being — “Evolving ‘Faith.'”

Lindon Eaves’ mention of the 16th-century mystic John of the Cross, who penned the term the “Dark Night of the Soul,” points at another way this radio pursuit of meaning, faith, and ethics has found its voice by listening to our guests and our listeners. They’ve taught us to explore what is dark and difficult in life, not just what is inspiring. We explore how frailties and failings define humanity as much as our strengths. Clinical depression, for example, is an epidemic of our age. Western culture knows how to discuss it pharmacologically, psychologically, culturally. I wanted to look at it existentially, spiritually. This was personal for me too. Clinical depression is part of my history and therefore part of my identity ever after.

Here’s part of a 2003 show we called “The Soul in Depression.”

MS. TIPPETT: Author and educator Parker Palmer, with whom I’m speaking now, experienced two crippling bouts of depression in his 40s. He recalls a particular thought offered by his psychologist, which helped him reclaim his life. The therapist said: “Parker, you seem to look upon depression as the hand of an enemy trying to crush you. Do you think you could see it instead as the hand of a friend pressing you down onto ground on which it is safe to stand?” Today Parker Palmer writes theologically about depression. He even traces his own collapse back to his midlife conversion to the contemplative Quaker tradition.

MR. PALMER: You know, I think you could make a case that, as a friend of mine once did — I mean, I actually went to a friend at one point. She happens to be a member of a religious community, a sister. And I said, you know, “I’ve been on this wonderful Quaker journey, and I’ve been sitting in silence and I’ve learned to pray, and I’ve been feeling so much closer to God than I ever did when I was just clinging to doctrine. Why am I now feeling so full of death?” And she said, “Well, I think the answer is simple: The closer you get to the light, the closer you also get to the darkness.” And it was another one of those phrases, like the one that my therapist gave me, that I didn’t understand right away, but right away I knew there was some kind of truth in it that I needed to try to understand.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, how do you understand that phrase now?

MR. PALMER: I understand that to move close to God is to move close to everything that human beings have ever experienced. And that, of course, includes a lot of suffering …

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MR. PALMER: … as well as a lot of joy.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. And, you know, and, again, just getting back to the subject of this show, the fact that — I think the thing in the midst of a depression that feels so absent, I would say, is your very soul, right? The ground of your being has dropped out.

MR. PALMER: Right.

MS. TIPPETT: And I don’t even think I could think about God one way or the other. I had to put the idea of God to one side.

MR. PALMER: Right.

MS. TIPPETT: And yet some of the most profound observations that you’re making and that you’re saying that can be possible out of some depression are precisely about those aspects of human experience.

MR. PALMER: Right. And, like you, the thought of God, all of those theological convictions, were just dead and gone during that time. But from time to time, back in the woods, that primitive wildness was there. And if that’s all God is, I’ll settle for it. I’ll settle for it easily and thankfully.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: When you were talking about how Quaker tradition — that people know how to be silent, I was recalling that passage in what you’ve written about your depression, about the friend who helped you the most, who would just come be with you.

MR. PALMER: Right. I’ll just tell that story quickly, because it’s such a great image for me. I had folks coming to me, of course, who wanted to be helpful, and sadly, many of them weren’t. These were the people who would say, “Gosh, Parker, why are you sitting in here being depressed? It’s a beautiful day outside. Go, you know, feel the sunshine and smell the flowers.” And that, of course, leaves a depressed person even more depressed, because while you know intellectually that it’s sunny out and that the flowers are lovely and fragrant, you can’t really feel any of that in your body, which is dead in a sensory way.

There was this one friend who came to me, after asking permission to do so, every afternoon about four o’clock, sat me down in a chair in the living room, took off my shoes and socks and massaged my feet. He hardly ever said anything. He was a Quaker elder. Somehow, he found the one place in my body, namely the soles of my feet, where I could experience some sort of connection to another human being. And the act of massaging just, you know, in a way that I really don’t have words for, kept me connected with the human race.

And it became for me a metaphor of the kind of community we need to extend to people who are suffering in this way, neither invasive of the mystery nor evasive of the suffering but is willing to hold people in a space, a sacred space of relationship, where somehow this person who is on the dark side of the moon can get a little confidence that they can come around to the other side.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: In addition to exploring the contradictory fullness of what it means to be human, we’ve also loved shining a light on the often-hidden human landscape behind the news. One of the most affecting conversations I have had across these years was with an Israeli woman, Robi Damelin, and a young Palestinian man, Ali Abu Awwad. She lost her beloved son David to a Palestinian sniper; he lost his beloved brother Yusef to an Israeli soldier. They are part of a quiet, passionate movement of citizen led change, called the Parents Circle — Bereaved Families Forum. It crisscrosses Israel, the West Bank, the Gaza Strip.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: I have to say that what being with the two of you reminds me of — and it seems pertinent because we’ve spoken about South Africa and because you’re from South Africa, Robi — that I did a program with two South Africans, Charles Villa-Vicencio, who was director of research for the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and Pumla Gobodo-Madikizela, who was on the Commission, a white man and a black woman. What was so striking to me, as much as everything they had to say, was the delight they took in each other and that they both said to me that when they grew up, you know, Pumla said she would never have imagined that she would have a white person as a friend or want a white person as a friend. And it was that friendship between them and that kind of delight and great surprise at being at this point in life and having this …

MR. AWWAD: Right.

MS. TIPPETT: … and I feel that with the two of you also.

MS. DAMELIN: It’s because we can laugh together. You see …

MS. TIPPETT: You can laugh together. Well, it’s — yes …

MS. DAMELIN: And we do.

MR. AWWAD: No, but I don’t love her anymore. She don’t want to marry me and she give up smoking and, you know, she’s doing that …

MS. TIPPETT: But you know — but the other thing that’s different with you — and this is serious — is, you know, when you talked about David and you talked about Yusef, it’s also like they’re part of this friendship and …

MS. DAMELIN: They are.

MR. AWWAD: They are.

MS. TIPPETT: … I think the two of you must — you feel like you know that loved one of the other, I can see that, and there must be a grief that you have also that you can’t — that you didn’t know them in life.

MR. AWWAD: I will tell you one thing — this is the first time I’m telling that. When I went with Robi to the place that David had been teaching in the yearly date that he get killed, we went to meet the student there. When I get to the library that David was preparing for the student, a good library, and I saw Robi start crying there, I don’t know, it’s strange, that feeling that I got at that moment. I have that feeling that David is telling me, “Take care of my mother.” This is the first time I’m telling that. I never told Robi that. And I think Yusef was so happy that Robi was taking care of me and I really don’t feel this identity when I feel about David, when I feel about Yusef. I don’t feel that. They just put us — by passing away, they put us in this deeply feeling with our humanity. And if people appreciate and if politicians appreciate the life as they appreciate the death, peace will be possible.

MS. TIPPETT: That conversation with Ali Abu Awwad and Robi Damelin took place in a Milwaukee hotel room that we transformed into a recording studio. That was one of the first interviews we videotaped and made available for viewing in its entirety on our website, onBeing.org. We also began to make our unedited interviews available for listening. These are just a few of the ways the digital revolution itself has opened up new platforms for exploring great questions of life. You’ll find a link to that video of Robi and Ali and others at onBeing.org, as well as all the shows we’ve curated for this hour.

Here’s a voice I cherish from 2003 — the late amazing Joe Carter, who never recorded a CD in his lifetime, singing and taking us inside the world of the spirituals.

MR. CARTER: [singing] for to carry me home

Tell all my friends I’m comin’ up there too, comin’ for to carry me home.

Why don’t you swing low …

MR. CARTER: I think there were so many of the songs, even “Wade in the Water” — “God’s going to trouble the water” — another image of people going to the river to be baptized and also going to the river to escape to freedom. The story of “Wade in the Water.” They loved that story. And the story was that a certain season the angels would come and trouble the water, as they say, which, I don’t know, they put their wings in or their toenails or whatever. But whatever happened, once they touched the waters, if you got in the water and you were sick, you’d be healed.

And so here’s this guy, 38 years he’s been going. And Jesus comes by and says, “What’s your problem?” He says, “Can’t you see? I’m a lame man. And every time the angels come to trouble the water, somebody gets in before me.’ And Jesus said, “Do you want to be healed?” “Well, yes. Of course, I do.” “Then take up your bed and walk.” They loved this story, because this was about self-sufficiency.

MR. CARTER: [singing] Children, wade in the water, wade in the water, children

Wade in the water

God is gonna trouble the water

Well who’s that yonder, dressed in red?

God is gonna trouble the water

Oh, It must be the people that Moses led

God is gonna trouble the water

Children, wade in the water, wade in the water, children

Wade in the water …

MS. TIPPETT: Coming up, more defining moments along the adventure of tracing religion, meaning, ethics and ideas in the modern world — including “Whale Songs and Elephant Loves,” “Seeing Poverty after Katrina”; and Desmond Tutu’s sense of humor.

I’m Krista Tippett. This program comes to you from American Public Media.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “Evolving ‘Faith.'” As the year turns and a decade ends, we’re looking back at the adventure of tracing the religious, spiritual, and ethical energies of a decade. In September, to reflect what we’ve learned along the way, we changed the name of this show from Speaking of Faith to On Being.

And it might be said that this change simply takes us more deeply into the original vision behind this program. “What does it mean to be human?” is the animating question behind religion, spirituality, also philosophy.

But it’s a question each of us pursues, with the raw materials of our lives. And the seismic changes of our time are taking that question itself onto new territory. From ecology to politics, we are reexamining the presumptions and the architecture of human life. In the process, many are also reexamining what religious words and practices mean at their very core.

This is what we heard from the physician David Hilfiker, in a program we called “Seeing Poverty after Katrina.” Over two decades ago, he moved his family to a Washington, D.C., neighborhood marked by the some of the same urban traumas that escalated tragically after Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans. Across the years, David Hilfiker has done fascinating research into the human causes of concentrated poverty and racial isolation in U.S. cities. He’s traced the role well-intentioned anti-poverty programs actually played in this. In Washington, he’s created, lived, and worked in several Christian-based programs for homeless people. And yet, he says, he’s never held a traditional faith in God.

DR. HILFIKER: I don’t experience God in ways that I recognize from what other people say about their experiences of God. I actually just read a passage from Walter Brueggemann’s book on Jeremiah, who quotes this passage from …

MS. TIPPETT: The prophet Jeremiah, the Hebrew prophet.

DR. HILFIKER: The prophet Jeremiah 22:16 says, “He cared for the poor and the needy; is not that what it means to know me?” And Brueggemann comments, “It’s not just that caring for the needy acquaints you with God, but caring for the needy is God.” And I don’t know exactly what he means by that, but I experience something like that. It’s something about living this way that is the deepest way that I can imagine to live.

MS. TIPPETT: Yet you talk about the limits of charity, and I sense that you are critical, in a way, of a move in our culture to locate justice strictly within faith communities, or to put a lot of the responsibility for this kind of practical justice on faith communities. Is that right?

DR. HILFIKER: Yes. Yeah. I don’t count the work at Christ House or Joseph’s House largely as justice work, I count it largely as charity work.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

DR. HILFIKER: My understanding of the difference is that within the Christian tradition, there is a mandate that we give charity and that we work for justice. And basically we give charity for ourselves. We give charity because it’s the right thing to do for our own spiritual health. We are in control of charity, we decide where it goes, who gets it. Often we decide what people have to do with our charity. We’re the ones on top, they’re the ones on the bottom. I mean, there is a whole host of problems associated with charity. I don’t criticize charity. It’s mandated, it’s something that we should do, and it’s what I’ve spent most of my career doing. But it’s different from justice.

Justice is working to change the structures so that the charity becomes less necessary. And that’s what is so essential and that doesn’t get touched by this turn in our country towards saying that faith communities will take care of the poor. I mean, there are practical reasons why that won’t work, but I think there’s a deep spiritual reason that charity is not enough, that we have to change these structures that benefit us and hurt them.

MS. TIPPETT: And I wonder as, let’s say, the immediate response to Hurricane Katrina is also the way we tend to respond to need when it is suddenly exposed, which is by writing checks, sending clothes, and that’s all good and, you know, and the Red Cross is out there saying, ‘Send money. Send money. That will do the most good.’

DR. HILFIKER: Right.

MS. TIPPETT: But I’m aware also, you know, raising children, that what they’re learning about how they help other people does have to do with writing checks and, you know, participating in a walk for hunger, you know? Which I would not want to discourage, I mean these are clearly good things with good intentions and good results, but somehow the way we do charity now also keeps us at a remove from what you’re talking about, which is real relationship.

DR. HILFIKER: Yeah. Well, I think maybe that’s the third leg of this. You know, we’ve talked about doing charity, which is mandated, we’ve talked about changing the structures, and the third leg is real relationships. And without those real relationships, you don’t have any good idea about how to change the structures.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: It’s been fascinating how this subject of relationship, the question not only of what it means to be human but of who we will be for each other — how that echoed also in the wake of the economic downturn of 2008. As that began to unfold, we wanted to supplement numbers — and argument-based analysis. And this became another turning point — where we realized with new clarity how you — our listeners — have become central to the editorial vision of this program. We are part of a web of relationship, catalyzed by the intimacy of radio and the capacity of new technologies. So beginning online in October 2008, we asked former guests and listeners to reflect on moral and spiritual aspects of economic crisis. We heard from people all over the world. Khalid Kamau had just been laid off from his job as a financial analyst in Manhattan. He sent us an essay, which we asked him to record for one of three radio programs that eventually emerged from that virtual conversation we called “Repossessing Virtue.”

MR. KAMAU: Once when I was young, I came home after school and baked a cake for my mom for dinner. I wanted to surprise her. She’s a nurse and had been at work all day, you know, before starting her second shift as our mom. So I pulled down a box of cake mix. And after I emptied the cake mix in the bowl, I saw that the recipe called for eggs, and we were out. I remembered the stories my family would tell about growing up in the rural segregated South. Though Jim Crow blacks suffered severe institutional oppression, their communities were strong and neighbors were always helping one another out. People would come over and ask for a cup of sugar or a loaf of bread, and “if you had it, you gave it,” my mom would say.

So that day, I went across the street to Miss Jessie, our retired neighbor; I got my two eggs and finished baking the cake. When my mother arrived, I presented her with the cake and proudly recounted all my efforts and resourcefulness. But the glow from her face quickly faded when I got to the part about borrowing the eggs. She called my father into the kitchen, and together they scolded me about going around the neighborhood begging for food.

It appears that in today’s culture, strong communities are those where estranged neighbors live on islands with no need for one another. Where sharing is not a practice of healthy community-building, but an act of last resort for the desperate and destitute.

In October 2008, when the market began to collapse, I secretly hoped the crash would be so complete that our middle-class pretenses would fall. Instead, what I see is a president, a Congress, and a marketplace eager to maintain the status quo. But they’re just taking their marching orders from us, the American people. It seems we’re still willing to do anything to keep from knocking on our neighbor’s door to ask for eggs.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: I love that story. I love how it speaks to the center of our common life, far from economic or religious debates — yet potentially transformative of them. It also points at moral and spiritual longings for community, for virtue, that transcend the religious/nonreligious divide. Here’s the thing. Across time our listeners have come to span the deeply devout in many traditions as well as agnostics and atheists. This is true for our guests as well. I’d say about half of the scientists I interview are themselves nonreligious people. Yet they are all asking questions that are spiritually evocative. They are enriching all of our understanding of both reality and mystery. And there was one pivotal show that helped crack open our editorial imagination on this, with a philosopher of science and poet, Jennifer Michael Hecht. I interviewed her in 2003 — before the new atheist revival. She had just published a gorgeous history of doubt across the ages. And she’s proposed that in this new century, identities of “atheist” and “agnostic” can be as limiting as some find labels of “religious” and “spiritual” to be.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: I copied down this longish quote from your book. It’s just such a beautiful piece of writing and — all right. “That we love and that love, among other possibilities, brings forth life is very strange. The birth of a child can bring extraordinarily religious feelings because it is such a good thing but also because it makes no real sense. Where did this miniature human being come from? Technically, we made it out of nine months’ worth of French toast, salad and lamb chops. Technically, our bodies hold tiny, little instructions for how to build human eyes, a language center in the brain, and a human spirit, fussy, joyful or otherwise. But how strange that such a thing as fussy exists and is created thusly.” I mean, you’re avoiding the word “mystery” there, but the word “strange” is a synonym for mysterious …

MS. HECHT: Sure. I don’t — I …

MS. TIPPETT: … in that case, isn’t it?

MS. HECHT: Yeah, absolutely. Yeah, and it seems that if you have a doctrine, a version of rationalism or a version of atheism that makes it so that you have to be worried about using the word mystery, you’ve got yourself too constraining a doctrine. And so I think that that’s what’s been so wonderful about doubters throughout history. They haven’t been an all-out turf war against religion. They haven’t been afraid — you know, Epicurus says, you know, “It feels good to pray, you might as well.” Now, that’s an amazing statement for someone who says that there’s no one listening, and the idea that we don’t have to be against religion or against the idea of mystery. How can you really be against the idea of mystery and have your eyes open at the same time? It doesn’t make sense to me.

But mystery, then, doesn’t mean I’ve got to fill in the blanks with, you know, ideas of my own imagination. Though, when people say that they’ve spent, you know, years in the desert and they’ve had certain experiences, I think that it’s perfectly reasonable to hold those experiences, those feelings. Or, you know, you don’t have to go off into the desert, just the feeling of faith, that’s an important thing. And I don’t think it needs to be dismissed in the kind of panic of, “We’ve got to control the other side.” You know, if we sort of can respect these ideas and say, “Yeah, life is mysterious. It is very strange.” Just the fact that, you know, we are these animals who have these kinds of thoughts, it’s all pretty wondrous, and doubters have celebrated it. And that’s the kind of doubt I want to bring into the conversation, because I think we’ve really backed ourselves into a couple of corners, and it’s time to get out.

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett on Being — Today, “Evolving ‘Faith.'”

As the hour draws to a close, I just want to dip into a few of the loveliest moments from the past decade — the first decade, that is — of this radio exploration of religion, ethics, and large ideas of meaning at the core of human experience.

There is Desmond Tutu, who teased me in the first moment we met, before the microphones were set up, embodying his theology that the God he knows has a sense of humor.

ARCHBISHOP TUTU: There we go. And I notice, I mean, you’ve got a glass of water; I’ve got a glass of water. But then you have dried fruit. Why — why do you rate dried fruit and I not?

MS. TIPPETT: [laughs] I brought this for you.

ARCHBISHOP TUTU: Oh, you …

MS. TIPPETT: Because your office told us that you love dried mango.

ARCHBISHOP TUTU: Oh, you beautiful thing. Oh. You are a star. [laughs] Can we say a prayer first?

MS. TIPPETT: Yes, please.

ARCHBISHOP TUTU: Come, Holy Spirit, fill the hearts of thy faithful people and kindle in them the fire of thy love. Send forth thy spirit and they shall be made and thou shalt renew the face of the earth. Amen.

MS. TIPPETT: Amen. You don’t know it but I’ve been trailing you for years waiting for this moment. So …

[Sound bite of music]

MS. TIPPETT: Then there is Katy Payne, an acoustic biologist, who spent her life studying some of the most exotic creatures on earth — deciphering the songs of whales and the loves of elephants.

MS. PAYNE: I see my responsibility, if I have one, as being to listen. My church is outdoors mostly. What’s sacred to me is this planet we live on. It’s been here for more than 4 billion years. Life has been on it only for 3 billion years. Life as we know it, you know, for a very short time. If I could ask these animals that I like so much if there’s anything equivalent to what we speak of as being faith, I would love to do that.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, right.

MS. PAYNE: We just don’t know. We just don’t know. [whale sounds]

MS. TIPPETT: And there is the amazing experience of hearing the voice of the great Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, in archival audio we dug up when we created a show about him in 2008. He marched with Martin Luther King Jr. at Selma, saying famously that he felt like his legs were praying. Here he is speaking in 1965.

RABBI ABRAHAM JOSHUA HESCHEL: I would say about individuals, an individual dies when he ceases to be surprised. I am surprised every morning that I see the sunshine again. When I see an act of evil, I’m not accommodated. I don’t accommodate myself to the violence that goes on everywhere; I’m still surprised. That’s why I’m against it, why I can fight against it. We must learn how to be surprised. Not to adjust ourselves. I am the most maladjusted person in society.

MS. TIPPETT: I can also never forget sitting with Matthew Sanford, a yoga teacher who has been paraplegic since the age of 13. He inhabits all of his body in a way so many of us long for as we think about what it means to be whole and healed while still imperfect — human.

MS. TIPPETT: I want to ask you about something you wrote: “I have never seen anyone truly become more aware of his or her body without also becoming more compassionate.” What’s that about? What’s that? Why is that?

MR. SANFORD: Well, it’s just true. It’s an observation.

MS. TIPPETT: But why do you think it’s true?

MR. SANFORD: I think it’s true for a lot — I think exactly — in my opinion, when mind separates from body, we get more self-destructive. We get more destructive in general.

MS. TIPPETT: If we’re more separate from our own selves, are we more separate from others as well?

MR. SANFORD: I think so. As you’re more in your body, you do feel more connected to people. You think about the importance of other life. And when you’re part of the world, it’s much harder to not feel compassion about the world.

[Sound bite of yoga practice]

MS. TIPPETT: And there is the end of our show with Kenyan environmentalist Wangari Maathai. She won the 2004 Nobel Peace Prize for her work of planting tens of millions of trees towards both ecological and political sustainability. At the end of our conversation, I asked her about music she likes, suggestions for songs that we might layer into the show with her. She spontaneously began to sing — a song she sings with women in the fields while they are planting trees — music that sustains her as much as any conviction.

MS. MAATHAI: [singing]

MS. TIPPETT: We finish with one of the earliest interviews we ever recorded. We knew from the first that the word “faith” was a complex choice for a public radio program title, meaningful for some, loaded for others. So to tease that out, to stretch our imaginations and that of our early listeners, we created a show called “The Meaning of Faith.” It included Buddhist teacher Sharon Salzberg, the writer Anne Lamott, Muslim theologian Omid Safi, and Rabbi Lawrence Kushner. He told me up front that faith is not a very Jewish word; but he then proceeded to offer stories and language that have informed my working definition of faith ever since. He even pointed then at where we’re going now.

RABBI KUSHNER: I was once working with a group of Jewish junior high school kids. This must have been 25, 30 years ago, and I asked them if they believe in God. And I was hoping, as a good teacher, that some would say yes and some would say no, and it would be a neat discussion. But no one said he or she did. And I was devastated. I mean, they didn’t even …

MS. TIPPETT: Just that they didn’t.

RABBI KUSHNER: Yeah, they “No, I don’t believe in God,” like “No, it’s not raining out.” I remember being devastated. I remember thinking, “So it’s come to this, 3,000 years of piety and struggle and agony for a bunch of obnoxious little suburban kids that don’t believe in God.” And I wanted to, you know, sort of wring their necks, and I don’t remember what I did. I probably did the equivalent of falling back a few yards to punt. And then later on in the discussion, I don’t know where it came from, I said, “By the way, how many of you kids have been close to God?” And so help me, every kid raised his hand. And that was a very eye-opening experience for me. And I realized that Jews will say, “I’ve been close to God, but I’m not sure I believe in God.” If you ask a Jew, “Do you or do you not believe in God?” they’re likely to regard it as something that’s put to them by the House Un-American Activities Committee. Like, “May I speak to my attorney? I’m not sure, you know.” But if you say, “Have you been close to God?” “Oh, well, yeah, I was close last Shabbes when Mother lit the candles, or, you know, when somebody I loved died, I was aware that the texture of religious time was different and that I was more intimate with the source of holiness in the universe.”

MS. TIPPETT: You wrote, “One reason we find talking about God so difficult is we are part of what we are trying to understand.” What makes that harder to talk about?

RABBI KUSHNER: It pushes the edge of language. No, but you’re absolutely right. I mean, one of the reasons that speaking of faith is such a slippery and a moving target is because we’re trying to talk about the stuff of which we are. We’re trying to take consciousness and turn it back on itself.

MS. TIPPETT: So that’s what we will continue to do next week and all the weeks after. As we explore meaning, faith, ethics, and ideas, we will push at the edges of language. We’ll converse about “the stuff of which we are.”

[Sound bite of music]

You can find and download all the shows featured in this hour at onBeing.org.

And I encourage you to subscribe to our e-mail updates. These bring you previews of each week’s show, my personal journal on each week’s ideas, and the most popular posts from our blog. Subscribe by clicking the “Updates” button on our home page — onBeing.org.

And we’re always looking for fresh, unexpected voices to contribute to our blog. If you write poetry or essays, produce multimedia features or photographs, become a guest contributor. Find the “submission” link on our home page, onBeing.org, and through our e-mail updates.

This program is produced by Chris Heagle, Nancy Rosenbaum, and Shubha Bala. Anne Breckbill is our Web developer.

Trent Gilliss is senior editor. Kate Moos is executive producer. And I’m Krista Tippett.

[Announcements]

Next time, as part of our ongoing Civil Conversations project, “Words that Shimmer.” I speak with the poet Elizabeth Alexander, about what poetry works in us, and why it may become more relevant, even for our common life, in hard and complicated times. Please join us.