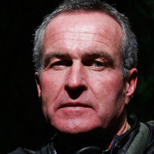

Gordon Hempton

Silence and the Presence of Everything

Acoustic ecologist Gordon Hempton collects sounds from around the world. He’s recorded inside Sitka spruce logs in the Pacific Northwest, thunder in the Kalahari Desert, and dawn breaking across six continents. An attentive listener, he says silence is an endangered species on the verge of extinction. He defines real quiet as presence — not an absence of sound but an absence of noise. We take in the world through his ears.

Image by Richard Darbonne, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

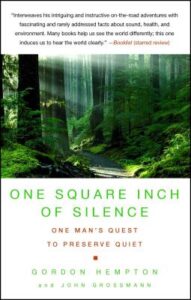

Gordon Hempton is the founder of the One Square Inch of Silence Foundation, which recently expanded to become Quiet Parks International with the mission to “save quiet for the benefit of all life.” His books include One Square Inch of Silence: One Man’s Quest to Preserve Quiet, co-authored with John Grossmann, and Earth Is A Solar Powered Jukebox: A Complete Guide to Listening, Recording, and Sound Designing with Nature. He’s also produced more than 60 albums of vanishing natural soundscapes. His latest release is a collection of soundscapes called Global Sunrise: The Musical Sounds of Dawn. His podcast is called Sound Escapes.

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: Gordon Hempton says that silence is an endangered species. He’s an acoustic ecologist; a collector of sound all over the world.

[recording of nature by Gordon Hempton]

He defines real quiet as presence — not an absence of sound, but an absence of noise. The Earth as Gordon Hempton knows it is a “solar-powered jukebox.” Quiet is a “think tank of the soul.” We take in the world through his ears.

[recording of nature by Gordon Hempton]

Gordon Hempton: Not too long ago, it was assumed that, eh, clean water’s not important, that seeing the stars is not that important. But now it is. And now I think we’re realizing quiet is important, and we need silence; that silence is not a luxury, but it’s essential.

[recording of nature by Gordon Hempton]

The last quiet places. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[recording of nature by Gordon Hempton]

Gordon Hempton lives between Port Townsend and Joyce, Washington, near Olympic National Park, a place he calls “the listener’s Yosemite.” I spoke with him in 2012. He’s recorded inside Sitka spruce logs in the Pacific Northwest, thunder in the Kalahari Desert, dawn breaking across six continents. His work appears in movies, soundtracks, video games, and museums. And Gordon Hempton may have invented “silence activism,” the other animating passion of his life.

[recording of nature by Gordon Hempton]

Where did you grow up? I didn’t see that anywhere.

Hempton: As a child, I was a member of a military family; started out in Southern California, then went on to Hawaii, then back to California before going to Washington, D.C., Seattle, San Francisco, and then I can say about a dozen other places before I got out of high school. So by the time it was my chance to go to college, that’s when I decided I’d fill the space in-between, by going to the Midwest, the University of Wisconsin.

Tippett: So there wasn’t really — there’s not really a place where you — which felt like a center of gravity, even with all that moving.

Hempton: Oh, there definitely is, and that is Hawaii. Yeah, the place of Hawaii, a place that I’ve recorded many times in my life, is — the first experience I had was when I was 6 weeks old. And then we moved away when I was 4 years old. And I did not revisit the location until 1990, when all of a sudden I discovered that I had all these primal impressions of what it’s like to be home in nature: the smells of Hawaii, the sounds of the surf, of all the places that I’ve recorded in Hawaii — and I’ve recorded all the islands in Hawaii, for an exhibit on endangered species for the Smithsonian Institution, because Hawaii, unfortunately, has the title of highest density of endangered species.

But I found the sound that I enjoyed most was the sound of the silence in the volcano. The measurement of decibels actually goes into the minus point, but there still is a sense of presence, of where you are. And then, once you get over the rim of the volcano, you begin to pick up what I call the mantra of the islands, and that’s the distant beating of that drum called the Pacific Ocean.

Tippett: Right. Was there a spiritual tradition or a religious tradition in your childhood, in your upbringing?

Hempton: Well, I was raised Episcopalian. And so that meant that every Sunday morning, I woke up and had to take that dirty pair of shoes that I always wore to school [laughs] and then put a fresh layer of shoe polish on them and then go to church. But I would have to say that sitting in church, I really had a hard time listening to the words, but I did enjoy listening to one thing, which is that everybody was coming together for a single purpose. And I particularly enjoyed the singing.

I really can’t say that I’m religious today, although I am spiritual. I don’t go to church that’s inside of buildings, but I do go to church that’s outside, and my favorite church of all is what I call the cathedral of the Hoh Rain Forest, at Olympic National Park. It has the world’s tallest trees, over 300 feet high, and it’s there that the least amount of noise pollution intrudes of anywhere else in the United States.

Tippett: And we’re going to go back there. We’re going to spend some time there, I mean, in our conversation. I am also, though, very intrigued when I look at your story, that you headed in this direction of becoming an acoustic ecologist, which — on its own, those two words, I think, are so intriguing and lovely. But you started doing that when you were living in a city, in Seattle. Is that right?

Hempton: Well, I did; actually, acoustic ecology didn’t even exist as a field. I grew up thinking that I was a listener. Except on my way to graduate school one time I simply pulled over — making the long drive from Seattle, Washington, to Madison, Wisconsin — pulled over in a field to get some rest. And a thunderstorm rolled over me. And while I lay there, and the thunder echoed through the valley, and I could hear the crickets, I just simply took it all in. And it’s then I realized that I had a whole wrong impression of what it meant to actually listen. I thought that listening meant focusing my attention on what was important even before I had heard it, and screening out everything that was unimportant, even before I had heard it. In other words, I had been paying a lot of attention to people, but I really hadn’t been paying a lot of attention to what is all around me. And it was on that day that I really discovered what it means to be alive as another animal in a natural place.

And that changed my life. I had one question, and that was, how could I be 27 years old and have never truly listened before? I knew, for me, I was living life incredibly wrong. So I abandoned all my plans, I dropped out of graduate school, I moved to Seattle, took my day job as a bike messenger, and only had one goal. And that was to become a better listener.

[recording of nature by Gordon Hempton]

Tippett: So there’s growth that comes from discovering something new, and there’s growth for human beings that comes from rediscovering something essential and elemental that we forgot. And it feels to me, as I immerse in what you do, that that’s huge. The ways you talk about that sound, in fact, connects everything; that our ears work all the time, [laughs] which is why our alarm clocks work — our bodies sleep, but our ears stay awake; and that, as you say, as human beings and as creatures like other creatures from the beginning of time, sound was a central way to make our way through the world.

Hempton: Sound is incredibly important. I’m always floored when I hear, over and over again from our modern culture, how important vision is; that, OK, sound is kind of important, but boy, vision is just —

Tippett: We’re very picture-centered, aren’t we?

Hempton: Well, of course, we’re picture-centered, because there’s so much noise pollution in our modern world today that if we were — [have] become auditory.

But I want to go back for a moment, and let’s just forget about the modern world, and let’s just look at evolution. Some animal species are actually blind. The ability to see is not essential for survival. There are blind animal species in the back of the caves, in the bottom of the oceans and stuff like this. But sound is so important that every higher vertebrate species has the ability to hear. And sight is such an affordable luxury that eyelids evolved. We can close our eyes: OK, that’s enough of that; I’m just going to close my eyes and take a break. But not once in the fossil record do we have any evidence that a species evolved earlids.

That would be far too dangerous. Animals must listen to survive. But here in our modern world, we’ve kind of forgotten that. But if we were to go to a quiet place, sit down in the Hoh Rain Forest, for example, and simply be alone in the silence of nature, that deep ability to listen occurs. And what do we hear?

Yeah, what do you hear?

Tippett: Let me ask you that question this way. Walk into the Hoh Rain Forest for me, with your ears. Walk us in there with you by sound.

Hempton: OK. So I get out of my car, all right? We’ll still hear the pinging of its engine. We’ll hear other cars and other visitors, and we’ll hear the beep-beep of our modern world as people are locking their cars, and the rustling of our artificial fabrics against our bodies. Some people will be chattering away on cell phones.

But then the sound of my backpack goes over my shoulders, and we head off down the trail. And no more than 100 yards along these tall, tree-lined, ferned path with moss drapes that add sound-deadening to the experience, we’ll hear the call-off twitter of a winter wren — [recording of winter wren by Gordon Hempton] — this very high-pitched, twittering sound that might be coming from 100 feet away.

[recording of winter wren by Gordon Hempton]

And then we’ll hear, further away, the sound of the Hoh River that drains the rain forest, echoing off the far side of the valley.

[recording of Hoh River by Gordon Hempton]

And if we were taking this hike in the fall, we would hear the bugling of the Roosevelt elk.

[recording of Roosevelt elk by Gordon Hempton]

Up close, it’s actually quite a guttural, adrenaline-filled assertion of what it means [laughs] to be male and wild. But when you hear this experience from a couple of miles away, isn’t that amazing? When you’re in a quiet place, your listening horizon extends for miles in every direction. When you hear an elk call from miles away, it turns into a magic flute, as the result of traveling through this place that has the same acoustics as a cathedral.

[recording of Hoh Rain Forest by Gordon Hempton]

I hear the presence of everything.

[recording of Hoh Rain Forest by Gordon Hempton]

Nothing shouts importance.

And often, I actually hike to One Square Inch of Silence with another person, and we agree not to talk while we’re there. And often the hike in is a chattery experience, coming from urban lives, etc., but the hike out is hardly talking at all. And if we talk, we always whisper.

Quiet is quieting.

[recording of Hoh Rain Forest by Gordon Hempton]

Tippett: One Square Inch of Silence, which Gordon Hempton just mentioned, is his project to preserve the natural soundscape in Olympic National Park’s backcountry wilderness. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being, today with acoustic ecologist Gordon Hempton.

[recording of Hoh Rain Forest by Gordon Hempton]

You have said that silence — and you mean that silence you just described — is an endangered species. I mean, is it right?

Hempton: Oh boy, silence is so endangered, we even need another word for it. Silence is on the verge of extinction. Places in nature that never have any noise pollution are already gone. The modern measure of silence is the noise-free interval. And now, we might think the noise-free interval should be measured in hours, for places that are very distant on the planet and even some places here that are isolated, such as Olympic National Park off of the northwest corner of Washington State. But if a place can have a noise-free interval of only 15 minutes or longer during daylight hours, it’s added to the list that I’ve collected for 30 years, called the “list of the last great quiet places.” At last count, here in the United States, there were only 12. None of them are protected.

Tippett: I want to talk about the language of silence and sound, “natural silence.” Sometimes you use it when you talk about these very few places …

Hempton: Natural silence, natural quiet.

Tippett: … quiet places where natural silence reigns over many miles. And you’re not, as you said a minute ago — you say this a lot — it’s not absence. It’s not a vacuum or an emptiness. This kind of silence is presence, and it includes sound, right?

Hempton: Oh yeah. It’s not the absence of sound. I think a physicist will tell you that true silence does not exist, not on planet Earth, with an atmosphere and oceans. When I speak of silence, I often use it synonymously with quiet. I mean silence from modern life, silence from all these sounds that have nothing to do with the natural acoustic system, which is busy communicating; wildlife are as busy communicating as we are. But it’s not just messages coming from wildlife — and I can name some that have been really transformative in my personal life — but it’s also the experience of place, what it means to be in a place.

Tippett: I kept thinking, when I was reading you, about a conversation I had with a physicist at one point who’d been really influenced by Goethe, who talked about some things that physicists talk about but from the perspective of a poet, and learning, remembering that light — that in fact we don’t see light, except in terms of what it falls on. And I was thinking about the way you talk about silence is that it’s always something that’s defined by — the quality of silence is relative to the sounds that are around it and against it.

Hempton: Oh, very much so. I’m in the process of going through and cataloguing 30 years of work, having circled the globe three times, collecting these experiences of silences. And I have two folders in particular, beyond all those other folders that are labeled insects, birds, frogs, forests, deserts, stuff like that; there are two folders —

Tippett: And sometimes you do wind, right? I mean, you do sounds that we almost don’t think of as sounds: grass waving.

Hempton: Oh, grass wind, oh, that is absolutely gorgeous — and grass wind, and pine wind — and we can go back to the writings of John Muir, which he turned me on to the fact that the tone, the pitch of the wind is a function of the length of the needle or the blade of grass. And so the shorter the needle on the pine, the higher the pitch; the longer, the lower the pitch. There are all kinds of things like that.

But the two folders where I collected, I have, oh, over 100 different recordings which are actually silent, from places, and you cannot discern a sense of space, but you can discern a sense of tonal quality, that there is a fundamental frequency for each habitat. And then my quiet folder is a folder which is a step above that, where you cannot distinguish any activity — you can’t hear a bird, a cricket, you can’t hear a ripple on a lake, you can’t hear any of the wind going through the pines — but you do have a sense of space. And each habitat also has a characteristic sense of space.

And these are the fundamental — to relate this to music, these are the fundamental tones that everything else is built up upon, so that when we listen to a place on planet Earth, we very quickly realize that Earth is a solar-powered jukebox.

Tippett: [laughs] Right. I love that. I love that sentence.

Hempton: Yeah, it’s a solar-powered jukebox. We can go to the equator, listen to the Amazon, where we have maximum sunlight, maximum solar energy. The solar panels, the leaves, are harvesting that and cycling it into the bioacoustic system. And to my ears, [laughs] that’s a little too intense. That’s a little bit too much action.

[recording of Amazon by Gordon Hempton]

And then we can jump up into Central America, and we can still feel and hear the intense solar energy, but it’s beginning to wane.

[recording of Central American rainforest by Gordon Hempton]

And we notice a really big difference when we start getting into the temperate latitudes, of which I particularly enjoy recording in because it’s not just about the sound.

[recording of nature by Gordon Hempton]

But it’s about something that I call the “poetics of space.”

Tippett: So say some more about that.

Hempton: Yeah.

[silence]

Silence is really wonderful, isn’t it, Krista?

Tippett: It is.

Hempton: Even when we just let it exist — let it exist — it feeds our soul.

Tippett: I remember having a conversation once with a rabbi who works with the spirituality of children. And she was talking about really practical things parents can do to nurture their children’s inner lives. And one of them was, she said, just create silence. Create spaces and times of silence, because that — I think we may have called it an endangered species. It’s something you have to actively make happen, in a modern family life. Right?

Hempton: [laughs] I get so many comments, when I give presentations and lectures, of people that come up to me afterwards, and they say, “You know, my child just doesn’t listen.” We’re all born listeners. And I always say, if there’s one thing you want to do as an adult to become a better listener, take a preschooler — someone who hasn’t gone to school and been taught how to listen by focusing attention, which is actually controlled impairment, but a preschooler who’s still taking in the whole world — hoist them onto your shoulders, and go for a night walk. They’ll tell you everything you need to know about becoming a better listener.

And if you have the good fortune of going for a walk up a nature trail with a child, the younger they are, the more pointless it seems to go any further, because the miracles are right here. Let’s just sit down, don’t worry about the exercise or the goals …

Tippett: The endpoint.

Hempton: … the expectations that you brought into the experience, and let’s just really be here.

That is often the big challenge for adults when it comes to silence, because we’re so busy being someplace else that, when we’re in a silent place, there are no distractions, we finally do get to meet ourselves. And that can be frightening. For a short while, it can be frightening — it’s practically fear of the unknown. [laughs]

Tippett: Well, I’m just thinking back to a couple of minutes ago, where you were quiet. And the truth is, there’s something scary about it. And it is that thing of you don’t know what’s going to happen next. And we’re kind of trained to fill the void where we meet one.

Hempton: Yeah. Anything can happen. It’s like the blank page to a writer. I take a moment of silence, every day in my life, that I don’t try to fill with thoughts, that I turn everything off — and sometimes that even means going over to the master breaker switch on the wall [laughs] and clicking that. And I know that other people might have other ways of saying it, but that’s what sounds right to me. There’s no purpose, but there’s a great deal of joy. I’m then able to go out into the day.

[recording of woodpecker by Gordon Hempton]

Tippett: After a short break, more with audio ecologist Gordon Hempton.

[recording of wind chimes by Gordon Hempton]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, the last quiet places, with audio ecologist Gordon Hempton. He’s a global explorer and collector of natural sound. He’s recorded the soundscapes of prairies, shorelines, mountains, and forests around the world. He defines silence not as an absence, but a presence, and an endangered species we must preserve. A quiet place, he says, is “the think tank of the soul.”

I want to then trace the silence back to the sound, because you do distinguish — we talked about that silence is not an absence of sound, it’s an absence of noise, and that there’s a lot of noise that we create; people create. But what I want to ask you, though, too, is as creatures among other creatures, what sounds of ours are part of the soundscape? You used this phrase, “the natural acoustic system,” right? I mean, surely, much of what we do is also natural acoustics.

Hempton: Oh yes.

Tippett: And it interests me when I read — when I looked at this documentary about — you love the sound of trains. Well, trains are inventions. They’re mechanical objects. So why —

Hempton: I get criticized about that from people who don’t like trains. But you know, I say, I don’t have to argue about the contradictions in my life. I just know that I love trains, particularly steam engines. OK, but it doesn’t —

Tippett: And the whistles.

Hempton: Yeah, and the whistles. And it doesn’t mean that I don’t also love silence.

Tippett: But tell me what the difference is. I’m saying, intuitively, I’m with you, and I think a lot of people love the sound of trains. But what is the difference between a train and the sound of a car or the hum of an electric generator?

Hempton: Oh, tremendous. Well, the difference is the message. A train, first of all — steam trains — the engineer, when he uses that horn, the whistle with the pull thing, he’s applying his own artistic sense, his own signature, the [makes whistle noise], his sense of timing. He is performing.

And then, as the train backs up, you hear the exertion, the force. It’s going over the clicking of the rails. It tells you the age of the tracks.

But most of all, when I listen to trains and their whistles from miles away, it’s like a whale letting out a sonar beep, and the whole topography of the surrounding landscape is revealed to me, and the many layers of the echo that come towards me, and I know exactly where I am.

Tippett: There’s that place again, that sense of place.

Hempton: There’s that place. You know, listening is not about sound. Don’t listen — if you ever find yourself listening for a sound, that’s diagnostically a [laughs] controlled impairment, all right? Simply listen to the place. And when you listen to the place, you take it all in, which is exactly what we’re meant to do.

Tippett: So where does music figure into your — this sensibility of yours?

Hempton: Well, I hear music coming from everywhere, and what I call music is basically defined as this: while I’m listening to it, do I want to dance? And when it’s over, do I find myself kind of like, humming it? Has it affected it? Myself, have I internalized it? Am I now living out those dance steps just in the way I interact with people or carry myself down the path? And I hear music coming from the land. Some of the most sublime symphonies have been hidden away in something as simple as a driftwood log.

And I’d like to share with you the sound of the most musical beach in the world, to my ears. It’s called Rialto Beach.

[recording of Rialto Beach by Gordon Hempton]

We’re about to enter into a giant driftwood log. It’s a Sitka spruce log, the same material that’s used in the crafting of violins, and it has a special property where that, when the wood fibers are excited by acoustic energy — in this case, it’s the sound of the ocean itself — that the fibers actually vibrate. And inside, we get to listen to nature’s largest violin.

[recording of inside of a Sitka spruce log by Gordon Hempton]

Tippett: So, obviously, there’s music, and there’s music. I get that. But when we —[laughs] that’s a discussion we’re not going to resolve here.

Hempton: [laughs] No, we aren’t going there.

Tippett: [laughs] When we human beings, when we put on music in the background of life, as a soundtrack to a place or a time or an experience: maybe sometimes, are we not just recreating what happens in nature, where the birds are singing and the grass is blowing? And there’s that —

Hempton: Oh, absolutely. I hear all the time, in folk music in particular — and I’ve been recording in Sri Lanka, for example, and spent a couple of weeks just recording the remote places there and the beautiful music that comes through the night, and all the insects and frogs weaving deep textures. And then I listen to the folk music, and I hear the same thing all over again. Our music is just a reflection of who we are, and who we are is what we hear. So I hear a lot of modern music as being the urban environment, the noise just being transformed.

Tippett: But I want to ask you this question positively, too. I just wonder if your children, or just your experiences as you grow older, if there are insights that are new to you, as you continue to listen even to our culture.

Hempton: Well, children of all ages, and adults, too, make their choices based on their experience to a much less degree than what they’re told. And that’s why it’s more important than ever that we do take those backpacking trips into wilderness areas, that we do allow them to get to that — through that first one or two days of sheer boredom, and then they make that adjustment. They feel their body coming into tune. That ringing of the ears ceases to exist. They meet an unexpected wildlife just right there on their shoulder, practically. Right? They notice things at night. They overcome how there are no streetlights, and things really do get dark and spooky at night, and how they wake up safely, and that there’s a grander experience in nature. But most of all, their thoughts will empty out, too.

[recording of birds at night by Gordon Hempton]

I’m Krista Tippett with On Being, today with acoustic ecologist and silence activist Gordon Hempton.

[recording of birds at night by Gordon Hempton]

You make some pretty stunning statements in your writing, just to take this a little bit farther, that research shows that in noisy areas people are less likely to help each other.

Hempton: Yes.

Tippett: And how do you explain that?

Hempton: The explanation really goes all the way to silence. When we can speak in silence, you can hear not just my words, but you can hear my tone, what I mean, even beyond the words. In fact, it’s really not the words that are important, it’s the tone. It’s the overall message, the context. When we’re in a noisy place, in urban environments, we become isolated, and we exhibit antisocial behavior, because we are cut off from a level of intimacy with each other. And we’re less in touch. We’re busy not listening to this, not seeing that, not doing that. We aren’t opening up and being where we are.

Tippett: I think this is really interesting, what you’re pointing at again: that intimacy is also related to being able to listen even at a very primal level; not even that we’re in conversation, but that we can hear; that we are listening creatures and that that somehow is destroyed or interfered with, in a very, very noisy environment.

Hempton: Listening — for all animal life, at least higher vertebrates, listening is our sense of security. And when we’re in a relatively quiet place, we can hear that all the information is in. So quiet places generally tend to be secure places.

Tippett: So they calm us — they calm our nervous systems?

Hempton: They calm us. We know all the information is in; the information isn’t being jammed. This happens in nature when a deer, for example, has to drink out of a creek, and then the noise of the creek blocks its ability to make surveillance, so it tries to compensate quickly, with glances with its eyes, and then it drinks. And then it moves back into a quiet place so it can continue to be secure.

And isn’t it amazing that our concert halls, our churches, places like that, they’re quiet places? They’re places where we can feel secure, secure enough that we can open up and be receptive and truly listen. And when we’re truly listening, we also have to anticipate that we might become changed by what we’ve heard.

Tippett: This is such an important point you make as a professional listener, and it’s something I know, too — that real listening is about being vulnerable.

Hempton: Yes.

Tippett: Right? But, I mean, I don’t even know that I know how to explain it. I mean, how do you explain that?

Hempton: Well, when you really listen, when you really keep your mind open and listening to another person — and by the way, I highly recommend that if a person wants to increase their ability to understand another person, that they start out listening to nature, because you’re totally uninvested in the outcome of nature. You can just take it all in, all the expressions. And isn’t it wonderful that when a bird sings, that we do hear it as music? The bird doesn’t sing for our benefit. So there’s a lot of joy in that listening.

And when we become better listeners to nature, we also become better listeners to each other, so that when another person is speaking with you, you don’t have to search for what you want them to say. You can dare to risk what they really are trying to say, and ask them, too, Is this really what you’re saying? and feel your own emotional response as they talk about risky subjects, like how it is being a parent in the world that it is today.

Tippett: So I actually think there’s something building here, in the culture at large. There was an article in The New York Times, by Pico Iyer, who’s a —

Hempton: Oh yes.

Tippett: Did you see that? “The Joy of Quiet.”

Hempton: Yes.

Tippett: He’s a journalist, a writer of books, an intellectual. And it was just the latest thing I’ve seen; it’s not the only thing. But it was about people leading very modern lives. He gave a bunch of examples. It ends with him running into — he goes to a monastery, and he runs into somebody who works at MTV, who brings his kids to this quiet place. And he ends it by saying — Pico Iyer ends it by saying, “The child of tomorrow, I realized, may actually be ahead of us in terms of sensing not what’s new, but what’s essential.” And he’s talking about quiet. And quiet is the element of — just like what you said — of discerning what is essential.

Hempton: Yeah, and that’s why it’s so exciting to be alive today, is because we are making these choices, rather than living a life of assumptions where quiet is not important. Not too long ago, it was assumed that eh, clean water is not important — but now it is, and we’re cleaning that up; that, oh, seeing the stars is not that important. And now I think we’re realizing quiet is important, and we need silence: that silence is not a luxury, but it’s essential. It’s essential to our quality of life and being able just to think straight.

[recording of wind and owls by Gordon Hempton]

Tippett: This also makes me think about something that I trace, which is how our ancient spiritual traditions gain a new kind of relevance, parts of them do, in this ultramodern world, because also, I mean, Pico Iyer went to a monastery. I mean, there are — religious spaces are some of those last places that are reserved for quiet. And it’s been very countercultural, but may be less so again. I don’t know.

Hempton: Well, recently, it’s been discovered that cave paintings — in France, for example — that show the staggered images of bison and other animals of the hunt, that those paintings occur in acoustically unique environments within the cave. And it’s believed that by listening, and listening to their echoes, that it was possible to commune with the spiritual world.

Tippett: Interesting.

Hempton: But you have brought up something really important to me, and that is about our ancient past. When I go to a quiet place, I get to challenge assumptions. And one of the major assumptions is that the human ear is tuned to hear the human voice. And if that were true — that’s an assumption that audiologists, scientists who study human hearing, have believed for a long time, that our ears evolved to hear the human voice.

Tippett: Right. [laughs]

Hempton: But if — [laughs] yeah, I know. But if that were true, we’d be the first species on planet Earth to have evolved so separate and protected from the rest of nature. So my natural curiosity was to look at the range of human hearing and these equal-loudness contours. And we have a very discrete bandwidth of super-sensitive hearing. And that’s between 2.5 and 5 kilohertz, in the resonant frequencies of the auditory canal.

Is there something in our ancestors’ environment that matches our peak hearing human sensitivity? Because most of what I’m saying right now, except for the “s” sounds and the high-pitched sounds, falls well below that range. And indeed, there’s a perfect match: birdsong. Birdsong. [laughs]

Why would it have any benefit to our ancestors to be able to hear faint birdsong? Why would our ears possibly have evolved so that we could walk in the direction of faint birdsong? Birdsong is the primary indicator of habitats prosperous to humans. Isn’t that amazing?

Now, when you’re in a quiet place, what is the listening horizon? If you ask a person that lives in a city, they might take a wild guess and say, Oh, you can listen for a mile. Right? They know it’s a trick question, so they’re going to pick something really big: You can listen for a mile. You ask somebody in the country: Oh, you can listen for three or four miles. And I’ve heard sounds 20 miles away: if you do the math, that is the size of 1,276 square miles. Do you know what it’s like to listen to 1,276 square miles when the sun is rising?

[recording of birdsong by Gordon Hempton]

Tippett: Gordon Hempton’s One Square Inch of Silence Foundation recently expanded its mission to become Quiet Parks International, with the mission to save “quiet for the benefit of all life.” His books include One Square Inch of Silence: One Man’s Quest to Preserve Quiet, co-authored with John Grossmann, and Earth Is a Solar Powered Jukebox: A Complete Guide to Listening, Recording, and Sound Designing with Nature. He’s also produced more than 60 albums of vanishing natural soundscapes.

And shortly after our original conversation in 2012, Gordon Hempton let us know that he experienced a dramatic loss in hearing. He made a move from suburban Seattle to the wilderness of the North Olympic Peninsula, living in a tent, hauling water, and chopping wood. During the pandemic, he and his wife again spent more time in Seattle, to be close to grandchildren. He tells us, “I hear both silence and the wilderness” in their voices.

His latest collection of soundscapes is called Global Sunrise: The Musical Sounds of Dawn.

[music: “Moonrise, IA” by The Pines]

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Laurén Drommerhausen, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Jhaleh Akhavan, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Ben Katt, Gautam Srikishan, Lillie Benowitz, April Adamson, Ashley Her, Matt Martinez, and Amy Chatelaine.

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear, singing at the end of our show, is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent, nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org;

Kalliopeia Foundation, dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality, supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org;

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives;

The Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education;

And the Ford Foundation, working to strengthen democratic values, reduce poverty and injustice, promote international cooperation, and advance human achievement worldwide.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.