When Things Fall Apart

Devendra Banhart with Krista Tippett

An excerpt from the in-depth On Being conversation between Devendra and Krista about Pema Chödrön’s book When Things Fall Apart.

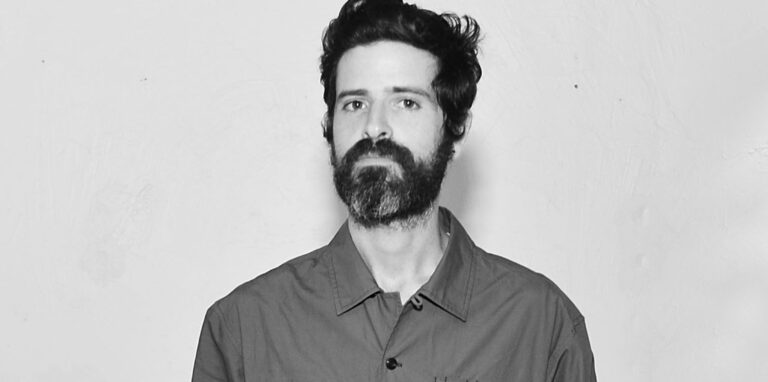

Devendra Banhart is a visual artist, musician, songwriter, and poet. His albums include Ma, Mala, What Will We Be, Smokey Rolls Down Thunder Canyon, and Cripple Crow, among others. His book of poetry is Weeping Gang Bliss Void Yab-Yum.

Listen to the whole produced show — and learn more about Devendra’s music and work — here.

Transcript

Krista Tippett: And the practice of tonglen, which Pema Chödrön also writes about, especially in this chapter, “The Love That Will Not Die” — I’ve read that that’s also something you practice on a daily basis.

Devendra Banhart: Yes. Tonglen — taking and sending — tonglen is really helpful. I don’t know if it helps anybody but me, though. It’s pretty selfish, actually. [laughs] But it’s like, how can I deal with reading the news, in a way. It’s like headline after headline of horror, and so how do I deal with it? And so you kind of treat reading the news each day like, OK, this is a way of dealing with so much horror in the news. I’m bearing witness to it, and then I will practice tonglen. I’m gonna breathe in all the suffering, the anger, the pain, the confusion, and I’m gonna breathe out healing and peace and wisdom and love and strength.

And that helps me, and it feels like I’m doing something, as opposed to just taking in all this horror and sorrow and sorrow. And you can practice it throughout your day. I don’t know if it’s the same for you, but every 15 minutes — I’m shocked at it, actually; that’s why I found a really quiet place in the house — but every 15 minutes I hear a siren or a cop siren, so ambulance siren or cop siren.

Tippett: You’re in L.A.? You’re in L.A. County?

Banhart: I’m in L.A. I’m in East L.A., and I don’t know, is it the ambulance going to pick up a body? Is it somebody that’s sick and needs immediate, critical, emergency care, or is this a crime? I’m not entirely sure, but it is consistent. It is every 15 minutes. And it began when this began. And so what do you do? I hear it, and I’m, “OK, I can practice tonglen.” This is kind of a way of somehow being proactive amidst the helplessness of so much suffering and horror around you. Now, this is the lay — the deep kindergarten version of it. And I’m — me, I’m the kindergartener. I mean, I’m really like, fully lay practitioner 101.

Tippett: Well, for doing the 101 tonglen, the way you described it really corresponds to how I feel Pema Chödrön describes it in this book. Do you want to read some from that chapter, “The Love That Will Not Die?”

Banhart: Absolutely. Chapter 14, “The Love That Will Not Die.”

“The father of a two-year-old talks about turning on the television and unexpectedly seeing the bombing of the federal building in Oklahoma City. He watched as the firemen carried the limp and bloody bodies of toddlers from the ruins of the day-care center on the building’s first floor. He says that in the past he was able to distance himself from other people’s suffering. But since he’s become a father, things have changed. He feels as if each of those children were his child. He feels the grief of all the parents as his own grief.

“This kinship with the suffering of others, this inability to continue to regard it from afar, is the discovery of our soft spot, the discovery of bodhichitta. Bodhichitta is a Sanskrit word that means “noble or awakened heart.” It is said to be present in all beings. Just as butter is inherent and milk and oil is inherent in a sesame seed, this soft spot is inherent in you and me.”

Tippett: I love that, “This kinship with the suffering of others.”

Banhart: I love that, too. I love that. And also, this is like — maybe at first you go, what is this? What am I talking about, “bodhichitta”? [laughs] And then all we know, all we hear — then later, we see this is a Sanskrit word, and it just means noble or awakened heart. And it’s something we all have. That’s it. This is not some exclusive thing — [laughs] something we all have.

Talk about hopeful. Talk about something to be like, whoa, it turns out I have this thing already. This noble or awakened heart is there.

[music: “Bedroll” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, I’m with the musician Devendra Banhart. We’re talking through our favorite passages of When Things Fall Apart, a classic spiritual work by Pema Chödrön.

I mean, this thing that she goes on to talk about in this chapter is that — so as you say, we all have this — we have this ability, this softness, this ability to know, be present to, to be in kinship with the suffering of others. And yet as we all, also, reflexively understand, it just feels like too much, as you said. Like reading the newspaper — I’m gonna try the tonglen, [laughs] because I can’t read it. I can’t read it all anymore.

But what she says — when we think that by protecting ourselves from suffering, which I think is what I’m doing when I’m just turning off the news, is, she says — “We think that by protecting ourselves from suffering, we are being kind to ourselves. The truth is, we only become more fearful, more hardened, and more alienated. We experience ourselves as being separate from the whole. This separateness becomes like a prison for us, a prison that restricts us to our personal hopes and fears, into caring only for the people nearest to us. Curiously enough, if we primarily try to shield ourselves from discomfort, we suffer.” [laughs]

So when you’re practicing tonglen — like reading the newspaper or whatever — I mean, she talks about this as a practice that, I mean, it can be ordinary. It can also be — somewhere she says — brushing your hair, listening to the rain, making music, [laughs] which you have some experience at. So it’s just a frame of mind with which you approach something? Or is that how it starts?

Banhart: Kind of — it’s definitely also a way of kind of unburdening yourself from yourself, too, because it’s a relief to care about somebody else. It’s really, it’s a relief to get out of your head, too. So like I say, I don’t know if it is helping that person that I’m sending that wave of love, of strength, of wisdom, of healing — I don’t know if it’s helping them. But it helps me.

And that’s the 101 kind of place to be, because — you know that classic story of when the airplane is — there’s no oxygen. You know, you don’t put the mask on the kid first, you put it on yourself, and then you can put it on the child. And it’s like, OK, you have to kind of work on yourself in order to be able to help others. And tonglen is a really, really wonderful way of having a kind of consistent practice of getting out of yourself and being compassionate for others and remembering that there are other human beings on this planet, because there is no shortage of the opportunity [laughs] to work on it, and especially now — especially now, there’s no shortage. There’s no shortage.

That’s why it is the sledgehammer of now-ness — like, whoa, this is this constant thing that is happening, and it is not just going away because we want it to. We are really forced to lean into the sharp edges more than ever. We are standing on a sharp edge. We’re sitting on it. [laughs] And the really cool thing about Pema Chödrön’s wisdom style is kind of — it’s about, be curious. There’s a kind of underlying “approach this fear, and approach this anxiety, and approach this heartbreak with curiosity” — like, “oh this is interesting. I’m just a tourist here, checking it out, taking photos. I don’t actually live in this place.”

Tippett: Because it is happening, whether you want it to or not, whether you like it or not. It is happening.

Banhart: Exactly. And can I approach it with this curiosity — “whoa, this is happening”? Or “aagh, this is happening.” This is kind of this attitude — can I just have a little bit more curious feeling about it? And then I can let the wave kind of pass, because wow, I don’t think I’ve ever personally felt, nor had, my friends and family feel so completely distracted and focused at the same time, and so completely exhausted and weirdly energized at the same time, and so completely overwhelmed by uncertainty and fear, than now. And it’s this tidal wave.

And so I’ll get a call or a text, and they’re going through the tidal wave — what is it, gonna happen? What’s gonna happen? And at that moment, maybe I’ll be in this feeling of, hey, it’s OK. I feel pretty calm. I can accept that I never know what’s going to happen, actually, so I can talk them through the tidal wave. And then I’ll need to call someone because I’m going through the tidal wave. But through it all, if I can remember Pema’s cool wisdom style of curiosity — like, oh, OK, I’m in a wave. This is interesting. Oh, OK …

[music: “Wasto Theme” by Blue Dot Sessions]