How to Be Grateful in Every Moment

David Steindl-Rast with Krista Tippett

An excerpt from Br. David’s in-depth On Being conversation with Krista.

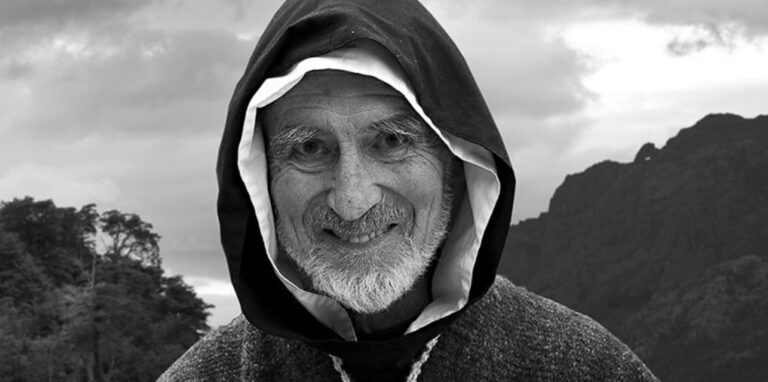

David Steindl-Rast is a Benedictine monk and a beloved teacher and author on the subject of gratitude. He’s the founder and senior advisor for A Network for Grateful Living. His books include Gratefulness, The Heart of Prayer: An Approach to Life in Fullness, A Listening Heart, and an autobiography, i am through you so i.

Find the full show — and learn more about his life, work and books — here.

Transcript

Krista Tippett: It’s interesting to me, I mean, you are part of this tradition, the Benedictine tradition, which is very much embedded in the great enterprise of the Roman Catholic Church and of Christianity, although monasticism in its many origins — monastic traditions arose as spiritual renewal movements; kind of what you’re saying — of a church that had grown institutional and imperial and lost its fire and its spirit. And so monastics, in a sense, have always kind of been rebels, in their way. And I find — and I know you must think about this — I mean, here we are in the 21st century, and your TED Talk had four million views, people watching a monk talk about gratitude. People are flocking to monasteries on retreat. And it seems to me that monasticism itself, even while it may look established, has always been something on the edges of religion. I’m thinking out loud, but I wonder if this is something you ponder.

Br. David Steindl-Rast: Yes, I completely agree with what you’re saying. I would express it differently — that monasticism was on the edges, in some respects, it was on the edges of the institution. That’s what you mean.

Tippett: Yes, that’s what I mean.

Steindl-Rast: But as far as the tradition is concerned, it was at the very heart …

Tippett: Driving to the core.

Steindl-Rast: … at the very core, because the core of every religion is the religion of the heart, and that is the monastic life. Of course, as an institution, and monasteries are also institutions, it also, again and again, hardens and becomes decadent and has to be renewed, but as an idea, the monastic life — all the different monasteries are a network of networks. Every monastery is a little network of monks and all the ones that belong to it.

It’s interesting, for instance, that today, when the number of monks in most monasteries — not everywhere; in other parts of the world, like in Africa and in Southeast Asia, Benedictine monasticism…

Tippett: They’re growing.

Steindl-Rast: … is growing, growing.

Tippett: Right, right. And they have many young people entering.

Steindl-Rast: Yeah, they are growing. But in the West, it’s getting smaller and smaller, as far as monks are concerned, but so many more lay people as oblates, as we call them, as extended family members that the monasteries, if you count the oblates, are bigger now than they were before. And for these lay people who live their own lives every day, but in the spirit, somehow, of monastic life, because there’s a monk in each of us — for them, this is really a great help in their lives and a help, also, to live gratefully. So yes, I think monasteries have a real special vocation in our time to work as a model.

Tippett: They have a new vocation, a renewed vocation. It’s a vocation that has evolved.

Steindl-Rast: Yes, it has evolved, because this power pyramid that has characterized our society, our whole civilization from the very beginning, for 5,000 years now — this pyramid of power, where even all our admirable culture and music and inventions and science is all bought at the price of oppression and exploitation. It’s very sad, but this power pyramid is in process of collapsing.

That’s what’s happening in our times. And if you speak to people who are close to the top, and I have been privileged to speak to people pretty high up in politics, in economy, in science, in all the different fields, medicine and so forth, and everybody says we have come to the end of the rope, things are breaking down — people who really have an insight — because this pyramid has no future.

Tippett: Right, the whole — the form and the structure of how we did power and created …

Steindl-Rast: It has to be replaced by network. And everybody knows that. And every group — monks are by no means the only ones. There are many, many communes and other groups out there that live network, or a network of friends, a network of women who serve. These networks, they are the future.

Raimundo Panikkar — you probably came across him, one of the great minds of the 20th century — said the future will not be a new, big tower of power. Our hope in the future is the hope into “well-trodden paths from house to house.” These well-trodden paths from house to house, that is the image that holds a lot of promise for our future.

Tippett: I was looking at a dialogue you had with a Zen roshi. And let’s say — you’ve been for a long time, even in the ‘60s — Thomas Merton became very well known for his dialogue with Buddhist monastics, and you’ve also been part of that, all this time, and I guess were with Thomas Merton in that great adventure back then, when it was so new. And you lived through a moment in the early 20th century, which arguably, as bad as we may feel it is now, was so much more horrendous, in terms of millions of people dying and global crises, people starving. You talked about the refugee crisis then, when you’d have literally people dying by the side of the road. And you were involved in that.

But you said something in this dialogue that — you said, actually, “We have had many thousands of crises in our history, but this world finds itself not only in a crisis, but on the brink of self-annihilation” — that the stakes are higher somehow now.

And I wonder if you would talk about that, but also talk about how, in this kind of moment, how is it even reasonable or how is it vital to talk about, to use language like “gratitude” and “gratefulness?” How is that a resource for us? How does it make sense in this moment?

Steindl-Rast: Yes, well, when we look at things like global warming or the destruction of the environment or this uncontrollable violence that’s breaking out, here and there, and you can’t touch it, you can’t grab it — that is really — I think that justifies us to say we are at the brink of self-annihilation. However, we must acknowledge our anxiety about it. We must acknowledge our anxiety, but we must not fear. And gratefulness is …

Tippett: We have to acknowledge our anxiety, but we must not fear.

Steindl-Rast: Not fear. There is a great difference. See, anxiety, or anxious, being anxious — this word comes from a root that means “narrowness” and “choking.” The original anxiety is our birth anxiety. We all come into this world through this very uncomfortable process of being born, unless you happen to be a cesarean baby. It’s really a life-and-death struggle for both the mother and the child. And that is the original, the prototype, of anxiety. At that time, we do it fearlessly, because fear is the resistance against this anxiety. If you go with it, it brings you into birth. If you resist it, you die in the womb, or your mother dies.

Tippett: So anxiety is a — not just an understandable, but a reasonable response to a lot of human experience.

Steindl-Rast: It’s a reasonable response, and we are to acknowledge it and affirm it, because to deny our anxiety is another form of resistance.

Tippett: Right, and so that is reasonable, but the fear is actually that moment of resisting.

Steindl-Rast: But the fear is life-destroying.

Tippett: And it’s a completely different move, and it takes us, our bodies, our minds, in a completely different direction.

Steindl-Rast: Destroys it, yeah. And that is why we can look back at our life, not only at our birth, but at all other spots where we got into really tight spots and suffered anxiety. Anxiety is not optional in life. It’s part of life. We come into life through anxiety. And we look at it and remember it and say to ourselves, “We made it. We got through it. We made it.”. In fact, the worst anxieties and the worst tight spots in our life often, years later, when you look back at them, reveal themselves as the beginning of something completely new, a completely new life.

And that can teach us, and that can give us courage, also, now that we think about it, in looking forward and saying, “Yes, this is a tight spot. It’s about as tight spot as the world has ever been in, or at least humankind. But if we go with it — and that will be grateful living — if we go with it, it will be a new birth.”

And that is trust in life. And this going with it means you look what is the opportunity —

Tippett: So — and I think, for you, what you’re getting at, for you, gratitude is as much about being present to the moment, but it’s also, to you, about seeing the opportunity in the moment beyond the current circumstances.

Steindl-Rast: And seeing the opportunity and availing yourself of the opportunity.

Tippett: OK, so it’s a very active — it’s very active.

Steindl-Rast: And that is very difficult, because anxiety has a way of paralyzing us, but what really paralyzes us is fear. It’s not the anxiety, it’s the fear, because it resists. The moment we give up the resistance — and so everything hinges on this trust in life. Trust. And with this trust, with this faith, we can go into that anxiety and say, “It’s terrible, it feels awful, but it may — I trust that it is just another birth into a greater fullness.”

Tippett: You’ve said that God is a direction, rather than a something.

Steindl-Rast: A direction, yes, but not an impersonal direction, you see? There is a wonderful line by Rilke, in which he prays to God — you know German, so I’ll say it first in German.

Tippett: And I love Rilke, as you do. Yeah, say it in German, please do.

Steindl-Rast: He says, “Ich geh doch immer auf Dich zu, mit meinem ganzen Gehen. Denn wer bin ich und wer bist du, wenn wir uns nicht verstehn?” So he says, “With every step I do, I go towards you. Because who am I and who are you if we don’t understand one another?” That is spoken to that great mystery. But when I say “mystery,” I mean not something vague, I mean something very clear.

Tippett: Well, that gets us back to that sense of belonging, that belonging at the core of …

Steindl-Rast: It’s right in there: “I go to you.” The moment a human being says “I,” at that moment, I have posited a “you.” That means I’m saying “I” because I’m related to a “you,” that mysterious “you” that is always here. And in that sense, this mystery is not something impersonal.

Tippett: It’s relational.

Steindl-Rast: It’s a relation. Ultimately, everything boils down to relation.

Tippett: You also said — I found this such an interesting — “Mysticism is the experience of limitless belonging.” That mysticism — because, again, I think that’s a word — you use the word “mysticism” in Western culture, and people might think of something very abstract and very elite.

Steindl-Rast: No, no. I believe that every one of us is a mystic, because we have this experience of belonging, once in a while, out of the blue, this — women often say when they give birth to a child, they have it; or when we fall in love, we have this sense of belonging. Or sometimes without any particular reason, suddenly, out in nature, you feel one with everything. And every human being has this.

But what we call the great mystics, they let this experience determine and shape every moment of their lives. They never forgot it. And we humans, the rest of us, tend to forget it. We just forget it. But if we keep it in mind, then we are really related to that great mystery, and then we can find joy in it.

[music: “A Little Powder” by Blue Dot Sessions]