Ilya Kaminsky

We Lived Happily during the War

The opening poem to Ilya Kaminsky’s masterpiece, Deaf Republic, is written in the voice of someone who is confessing their complacency during a time of trial. There’s a war going on, but it doesn’t affect the person speaking, so they don’t get involved. Instead they stayed outside and caught the sun. They lived happily during the war, and are now saying (forgive us). This poem leaves us wondering what it would mean to make such a confession, to ask for forgiveness, and whether it’d do any good.

Letterpress prints by Myrna Keliher | Photography by Lucero Torres © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Ilya Kaminsky was born in Odessa, former Soviet Union in 1977, and arrived in the United States in 1993, when his family was granted asylum by the American government. He is the author of Deaf Republic and Dancing In Odessa, and has co-edited and co-translated many other books, including Ecco Anthology of International Poetry and Dark Elderberry Branch: Poems of Marina Tsvetaeva. He holds the Bourne Chair in Poetry at Georgia Institute of Technology and lives in Atlanta.

Transcript

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and I, like lots of people, had been waiting for the book Deaf Republic, by Ilya Kaminsky, to come out for months. It was eagerly anticipated. And I was flying home from Minneapolis to Ireland, and I was able to buy it in the airport. And I’d read it three times before I arrived back in Dublin. It was Ash Wednesday, and so I and loads of other people had ashes on our forehead. And I always associate this book with reading it on packed planes with people who had ashes on their forehead, a book that asks people to pay attention to their complicity.

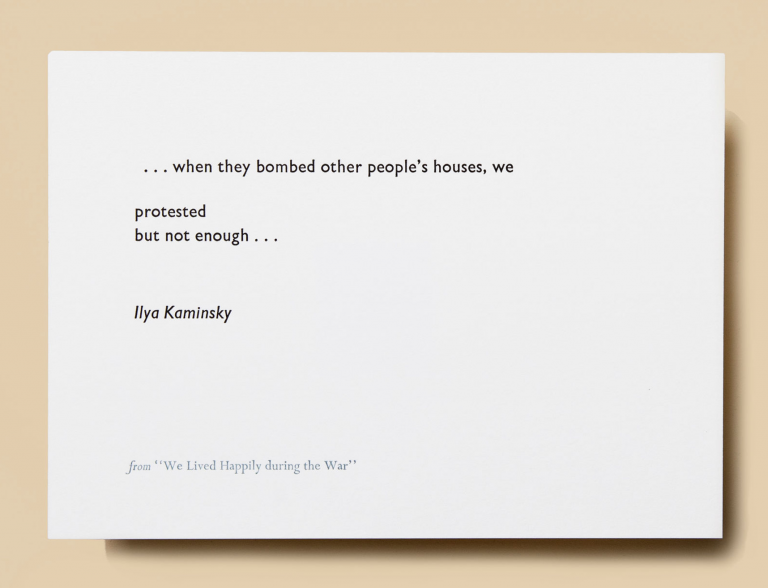

“We Lived Happily during the War” by Ilya Kaminsky:

“We Lived Happily during the War”

“And when they bombed other people’s houses, we

protested

but not enough, we opposed them but not

enough. I was

in my bed, around my bed America

was falling: invisible house by invisible house by invisible house—

I took a chair outside and watched the sun.

In the sixth month

of a disastrous reign in the house of money

in the street of money in the city of money in the country of money,

our great country of money, we (forgive us)

lived happily during the war.”

[music: “Every Place We’ve Been” by Gautam Srikishan]

So this poem, “We Lived Happily During the War,” it’s the opening poem in a book called Deaf Republic, by Ilya Kaminsky. And the book Deaf Republic is a poetry collection, but it’s also a story, almost like a piece of theater — it has a cast of characters at the start. And reading through the poems, you’re learning about these characters, and you’re wondering, what’s going to happen?

Ilya Kaminsky was born in Odessa, in the former Soviet Union, now Ukraine, and his family sought asylum in the States, in the 1990s. And the broad storyline of the book is a city or a town called Vasenka — this town maybe sounds like it could be somewhere in Russia. And this book is an exploration about what happens in the city of Vasenka when, at a performance in the town square of a puppet show, soldiers shoot a deaf boy. And the community decide to not listen, as their ethical response. And they coordinate their communication and subterfuge with each other through sign language.

Ilya Kaminsky is deaf himself, and so he is exploring deafness as an ethical response to oppression. He has this fictional town, but also, this fictional town is every town. In this opening poem, he mentions America. He is asking people who are reading the poem or listening to the poem or engaging with it to feel implicated in the question about civic life, and who is comfortable while other people aren’t, and how can you remain comfortable while other people are oppressed.

[music: “White Filament” by Blue Dot Sessions]

The use of repetition in this poem makes it sound what you would call, in literary criticism, “lyric,” coming from the word “lyre,” which is like a little harp that originally, in Greece, people would’ve strummed while they were reciting poetry. This is a devastating poem about complicity, but yet it has the consolation of lyric poetry. And that’s a really interesting contrast, a poem almost of self-accusation. The poem begs for forgiveness at the end, but the poem also has something of tenderness in it. And it is deliberately not creating and stoking outrage, because, I think, he’s saying that outrage can sometimes flare up but not be carried through on. It is saying, how might we make a serious reckoning with ourself in language that can sing?

And so you have this “not enough … not enough,” we hear at the start. And then we hear about houses at the start, as well as “invisible house by invisible house.” And then we think of “the house of money” and “the street of money,” “the city of money,” “the country of money, / our great country of money.” So the word “house” is repeated five times, and the word “money” is repeated five times.

I think the word “house” in this poem plays a function as to think, who do you think is in your household? If only the people in your household are comfortable, is that enough? Who do imagine is in your broader household? And the book, I think, is asking people to pay attention to the question as to what is the border of their household that they define.

And money, I think it’s highlighting that in situations of war — because he is speaking about his own upbringing. He’s also speaking about years when he lived on the Californian border with Mexico and speaking about so many different places where there is escalated tension or even war and how lots of people know you can make a profit from fear. You can make a profit from war. Over and over again, in situations of war — we know this in Ireland — things will be happening where conflict is escalating, people’s lives are in danger, and somebody will see an opportunity for profit making. And he’s highlighting here that many of the justifications that people use for justifying their wars are actually just shallow and hollow justifications for a profit making industry that profits from the question of people’s conflict and the ending of people’s lives.

[music: “Union Hall” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Toward the end of the poem there is this request: “forgive us.” There is tremendous tenderness in that. I don’t hate the person speaking, even though I pity them and even though, also, that person might be me. The “forgive us” is in parentheses: “we (forgive us) // lived happily during the war.” So why are they saying, “forgive us”? The whole way throughout this poem, when someone’s saying, “We lived happily during the war,” we’re hearing a voice that’s accusing itself. It isn’t saying, “They lived happily during the war” or “You lived happily during the war.” It’s saying “we.” And it isn’t blaming those who did the aggression of bombing other people’s houses, but rather it’s begging for forgiveness for having taken a chair out to watch the sun while a country is falling all around you.

And so I suppose one of the questions that we’re left with by paying attention to this “forgive us” is, would you forgive the speaker of the poem? And if you were the speaker of the poem, would you want to be forgiven? Do you think you could be forgiven? Who needs to be forgiven? Who feels the need for that in situations where there are communities of people who are experiencing a certain kind of luxury while other people are experiencing oppression? This voice of “forgive us” is asking the reader, I think, to consider, what might the journey be for you, in the journey of saying, “Hey, that’s got nothing to do with me. I was just living my own quiet life” to the stage where you yourself are going to say, “forgive us”?

[music: “Angel Tooth” by Blue Dot Sessions]

There is a deep and very interesting politics of disability in this poem. In English, you often hear people saying, when they’re describing an action or ignorance, they might say, “Oh, I was blind to that,” or “It fell on deaf ears.” And this poem, and the whole book really, uses choosing not to see and choosing not to listen as moral reckonings that don’t prey on questions about impairment.

Years ago, when I worked for the Irish Wheelchair Association, I had a boss, Maureen McGovern, a disabled woman herself and a disability rights worker. And she used to always say to me, “Don’t use my impairment as a metaphor for your ignorance.” And it changed my use of language, when it came to using words like “deaf” and “blind” or “wheelchair-using” for anything other than simply describing a population of people. And in other words, I suppose what she was saying to me was, say what you mean to say. Don’t use deafness or blindness or whether a person walks as shortcuts to talking about stubbornness or ignorance or moral turpitude. And I think in this poem what we see is where people are choosing not to see what’s happening all around them.

But the term “watched the sun” is very interesting. Do we watch this burning star? “Sunbathe” is usually what people say, and you can burn your eyes from watching the sun. So somebody saw these things happening and chose instead to look at something else, some other kind of burning, a kind of burning that brings perhaps a reward of a suntan or feeling warm in the sun while meanwhile other people were being burnt. And the opening poem, in a certain sense, is about the cowardice of people choosing not to see the awfulness about what’s going on all around them.

And the rest of the book, the book called Deaf Republic, is the story about what happens in a fictional city of people who choose not to listen to the voices of violence. This opening poem is the luxury of choosing not to see, and the rest of the book is a moral reckoning with choosing not to obey, choosing not to listen, choosing to find new methods of communication in order to move against actions of oppression from an army.

[music: “Thread Caramb” by Blue Dot Sessions]

So I think lots of people might know that piece of writing by Martin Niemöller where he says, “First they came for the Socialists, the trade unionists, the Jews, and then me.” Martin Niemöller was German, he was Lutheran, and he was reckoning with his own inaction. He had actually initially supported Hitler’s rise to power and then later on turning against Hitler and leading to his own incarceration in concentration camps. He was one of the ones liberated, and he was a voice for penance for decades afterwards. It was so important, because he wasn’t asking for forgiveness. He was in a certain sense highlighting his own complicity and saying, as a result of that, his ethical response was about penance.

And I think what he’s doing is highlighting over and over again, in so many places of war, that while some people are wondering, “Will I survive the day?” somebody else is wondering what color to paint the kitchen or whether they should reupholster the chairs or what choice to make about holiday. There’s a brutality about that. This poem isn’t, I think, trying to make us feel guilty about those things, but it is trying to say, “Are you doing enough?” Because the poem has the invitation to say, “we protested / but not enough, we opposed them but not / enough.” So what is the “enough” going to be?

That’s something that people have to reckon with for themselves, but certainly, this poem is inviting us to think about the enough and move toward that rather than just thinking of the bare minimum.

[music: “Every Place We’ve Been” by Gautam Srikishan]

“We Lived Happily during the War” by Ilya Kaminsky:

“We Lived Happily during the War”

“And when they bombed other people’s houses, we

protested

but not enough, we opposed them but not

enough. I was

in my bed, around my bed America

was falling: invisible house by invisible house by invisible house—

I took a chair outside and watched the sun.

In the sixth month

of a disastrous reign in the house of money

in the street of money in the city of money in the country of money,

our great country of money, we (forgive us)

lived happily during the war.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Lily Percy: “We Lived Happily During the War” comes from Ilya Kaminsky’s book Deaf Republic and was originally published in POETRY magazine. Thank you to The Permissions Company on behalf of Graywolf Press, who gave us permission to use Ilya’s poem. Read it on our website at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Chris Heagle, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, and me, Lily Percy.

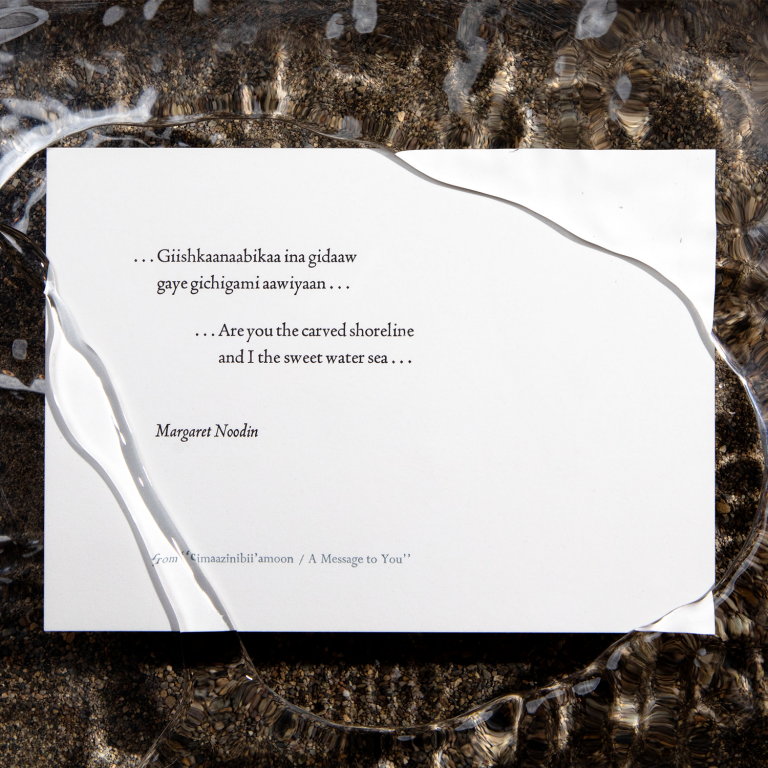

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions. This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land.

We also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me. Find those wherever you like to listen, or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.