Jacob Shores-Argüello

Make Believe

In a short poem recalling a childhood response to grief, Jacob Shores-Argüello brings us into the fantasy world of a child: leaving an ill adult in a hospital bed, he and his cousin take to the mountains, turn magically into bears, and begin tearing holes in the earth for rest while the world continues below. Are they escaping? Or playing with rage? This extraordinary poem is a thing of wonder and survival.

Letterpress prints by Myrna Keliher | Photography by Lucero Torres

Guest

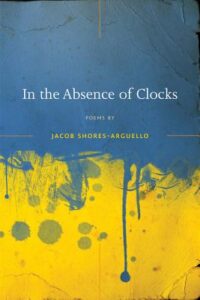

Jacob Shores-Argüello is a Costa Rican American poet and prose writer. He is the author of poetry books In The Absence of Clocks and Paraíso, which was selected for the inaugural CantoMundo Poetry Prize judged by Aracelis Girmay. He is a 2018/019 Hodder Fellow at Princeton University and a Lannan Literary Fellow for Poetry. His poetry appears in The New Yorker, Poetry Magazine, and The Academy of American Poets, among others. His fiction appears in The Oxford American, among others.

Transcript

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and when I was a small boy, myself and my friend David used to cycle a few miles away from the house and find an abandoned house and start to pull apart the bricks that made up that house. I don’t know how old this particular farmhouse was, but it was huge. And nobody lived there. It hadn’t been lived in for years. And there was something about me and David working away quietly, side-by-side, listening to the crashes of stones, that meant that we had a lovely friendship. But actually, we rarely spoke to each other.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Make Believe,” by Jacob Shores-Argüello.

“As children, my cousin and I once

dug into the side of our mountain,

a terrible brown work.

That morning we’d made the cold walk

to the hospital and watched

his mother for a long time.

She was unchained from her machines,

shrinking into ordinary.

It was our first death,

and we looked at our small hands.

But no, my cousin insisted,

these are not our hands,

they are bear hands.

And we walked to our mountain,

shaped our cave:

one meter, two meters, three.

We bears were making a home.

We roared, and shook off our human bones,

until angels howled like dogs

in the valley below.”

[music: “Memoriam” by Gautam Srikishan]

This poem is from Jacob Shores-Argüello’s book Paraíso, which is a book really about grief, but not grief about his auntie, grief about his own mother. And it is grief in place — particularly, Costa Rica. He’s a Costa Rican American poet. And Costa Rica is a really powerful character the whole way throughout this book. And there are other characters in the book, as well as in this poem — grandfather, uncle, cousins. And there’s time, there’s childhood, and then places like rivers, and places where he’s had car crashes, and here, the mountain. All of these features, these people, these places, and time, take on particular characters of importance in this book that’s a long meditation on grief.

One of the reasons why I love this poem so much, and there are many reasons why I love this poem, is because it starts off as an adult reflecting on being a child. “As children, my cousin and I once / dug into the side of our mountain.” And you even hear the adult voice at the start there, saying, “a terrible brown work.”

But then it goes into the experience of childhood, and it doesn’t emerge from it. And I kind of like the way that the voice of the child comes through, criticizing, perhaps, the older poet, Jacob Shores-Argüello. It’s his child self, criticizing the adult self that was categorizing this project of these two grieving boys, these two grieving cousins digging into the side of the mountain. No longer is it being described as a “terrible brown work.” It’s being described as something that makes angels howl like dogs, and they roar, shaking off human bones — that somehow, their escapism worked. And that, I think, is one of the extraordinary things in this poem.

[music: “Taoudella” by Blue Dot Sessions]

So this poem is about the poet, Jacob Shores-Argüello, and his cousin, and they’re facing into his cousin’s mother’s death. And in the face of death, they pretend to be bears. And the cousin is the one who instigates this make-believe, and the poem is called “Make Believe.” So they dig a cave into the side of a mountain and listen to the noises from below.

There’s so much observation in this poem: the observation of it having been a cold walk to the hospital, and machines, and then the cousin’s mother being “unchained” from those machines. And that extraordinary line, she’s “shrinking into ordinary” — what does that mean? Is she shrinking into ordinary now because, suddenly, with the machines being unattached, she seems smaller than they had seen her previously, perhaps, being attached to larger machines? Maybe she’s ordinary because she’s her, now, and not hospital, and ordinary, too, because she’s dying.

And one of the things that’s really powerful in this poem is, hidden in the midst of the poem about make-believe and bears and howling angels is a poem about how children can have a clear-eyed understanding about death, and naming, as this child voice does, that in “shrinking into ordinary,” she’s also shrinking into death.

That is a demonstration of the ways within which children can hold fantasy and clarity at the same time, because they have a clarity in this poem that she’s dying. And in the midst of that clarity, they look at their hands — it’s their first death — and then suddenly, they’re not their hands anymore, they’re bear hands. Play and reality are partners in this poem, and not partners that are in tension — partners that are in profound relationship with each other.

[music: “Ashed to Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

In any poem, there’s always going to be multiple things happening underneath the surface. So on the surface of this, it’s a poem about make-believe and a poem about grief. It’s a 20 line poem, and those 20 lines are split up into ten couplets; ten two-line stanzas. And in a way, what the structure of this poem is saying is that it’s nice to be together with somebody. And these two cousins are companions. In the midst of everything else, all the blank space of grief and all the absentness of this cousin’s mother, you’ve got these two lines the whole way across the page in this poem that are reminding us that it can be nice for someone to have a companion.

There are so many plural pronouns in this poem, and some of them are obvious, but others are strange. And the repetition of all of these plural pronouns alerts us to the mystery of why we’re drawn towards each other, and even how two people can be together in solitude and that can be a powerful thing. So you hear “the side of our mountain” and “we’d made the cold walk to the hospital.” And they speak about “our first death.”

And Jacob Shores-Argüello says, “we looked at our small hands.” “These are not our hands,” the cousin says, and then “we walked to our mountain” — again, that ownership of the mountain comes in — “shaped our cave.” “We bears,” “We roared, and shook off our human bones.”

There’s the play at becoming a bear, and that’s important, but underneath all of that there’s the real strength of the reality of being together. And how many of us, in whatever grief we’ve gone through in our life, would’ve liked somebody who could’ve entered into the reality of our grief, as well as the fantasy of responding to that grief, with us?

[music: “Toothless Slope” by Blue Dot Sessions]

I’m curious, in the fantasy of this poem, about why a bear? Maybe it’s just a primal image. Bears belong to the mountain, and the mountain belongs to them, much like these boys are talking about belonging to the mountain and the mountain belongs to them. And bears are powerful, and they roar, and they can dig a home into the side of a mountain and hibernate, escaping from the howls. And perhaps these boys, too, would like to be able to create a new sense of home, as well as create a sense of being able to escape and hibernate for a while.

It is a cold walk to the hospital, so maybe it is winter. Maybe they felt a desire for a long sleep after grief. And perhaps the cousin wanted his other cousin for company in this retreat. They wanted to be away and above, and so much of that makes sense to these desires of wanting to escape when we’re faced with death.

Often, escapism is spoken of as if it’s some kind of derogatory term — “I read an escapist book. I watched an escapist movie.” But J. R. R. Tolkien says that escapism isn’t such a bad thing, if you find yourself in jail. And certainly grief, and especially in the earliest moments, here, is probably being experienced like some kind of suffocating jail, some suffocating place from which you wish to escape. And these boys want the two things — to be above, as well as enclosed; above the valley of grief and then enclosed in this cave that they’ve dug together. And grief is exhausting and consuming, and everybody’s looking at you. And they want to be together, but also away from the howls.

[music: “What Did You Not Hear” by Gautam Srikishan]

You know, years ago, a friend of mine died. And he was the first friend of my own age who I had loved, who died. I was in my early 20s. And I was in such shock. And another friend of mine said, “Do you want to do something? How can I help?” You know the kinds of things that people say. And I said, “Can we go to the cinema?” And I have no idea why that popped into my mind. I actually don’t go to the cinema that often. But I think I, too, wanted to escape.

And reading this poem from Jacob Shores-Argüello, I found myself reflecting on that moment that these two boys, these cousins, were with each other in companionship, while they escaped into something of fantasy. And both companionship and the fantasy were important to each other, because what you choose in fantasy is really important. You know, they’ve gone to the mountain. They’ve gone up a bit. They’re imagining themselves as these primal bears — they’re not human anymore. Maybe they’re not wishing to be in grief. But at the same time, they’re digging a place for some kind of enclosure or hibernation.

But perhaps, too, they’re digging a grave. Is that in order to be closer to the mother character who’s died in this poem? Are they preparing it for her, maybe even hoping she might join them in this small grave, small cave in the side of a mountain? So the choice of fantasy, the choice of play from amongst all the things that they could’ve played with, the choice of cave and mountain and digging — all of those things are really important.

[music: “Memoriam” by Gautam Srikishan]

So I think this is a very tender and gentle poem about paying serious attention to the substance of play. You know, it invites adults to step back from an adult judgment of play, because quietly, in the background of this, I wonder who were the relatives that might’ve said to those boys, “What are you doing wasting time?” or “You know what these boys did just after his mother died? They went off and they dug a hole on the side of a mountain.”

But quietly in this poem, too, is the presence of the woman who died. And I wonder what she might have said, and partly I wonder if she’d have said, “How lovely that they had each other for company.” Or she might have said about her son, “He’s always loved bears.” Or she might have said that she was sad to be leaving, and she was very glad that they had company in each other’s kindness and company in each other’s play and company in each other’s imagination.

What’s so interesting is that most of this book by Jacob Shores-Argüello is a reflection on his own mother’s death. And here in this poem, he’s not reflecting on her, he’s reflecting on the first death, the cousin’s mother’s death. And in that, he too, as an adult, is reaching out for the company of his cousin. So it shows that the company that we keep during times of grief goes far beyond that single time of grief and goes somehow deep into the soul, into the psyche.

And this, I think, is the imagination of the poem, and the invitation of the poem, too. Who is it that you turned to? What fantasy did you turn to? Maybe that fantasy is wiser than you think. Maybe the escapism of it is worthy of giving attention to.

[music: “Memoriam” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Make Believe,” by Jacob Shores-Argüello.

“As children, my cousin and I once

dug into the side of our mountain,

a terrible brown work.

That morning we’d made the cold walk

to the hospital and watched

his mother for a long time.

She was unchained from her machines,

shrinking into ordinary.

It was our first death,

and we looked at our small hands.

But no, my cousin insisted,

these are not our hands,

they are bear hands.

And we walked to our mountain,

shaped our cave:

one meter, two meters, three.

We bears were making a home.

We roared, and shook off our human bones,

until angels howled like dogs

in the valley below.”

Chris Heagle: “Make Believe” comes from Jacob Shores-Argüello’s book Paraíso. Thank you to University of Arkansas Press, who gave us permission to use Jacob’s poem. Read it on our website, at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, and me, Chris Heagle.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions. This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land.

We also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me. Find those wherever you like to listen, or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.