Janine Benyus and Azita Ardakani Walton

On Nature's Wisdom for Humanity

In this all-new episode, Krista engages biomimicry pioneer Janine Benyus in a second, urgent conversation, alongside creative biomimicry practitioner Azita Ardakani Walton. Together they trace precise guidance and applied wisdom from the natural world for the civilizational callings before us now.

What does nature have to teach us about healing from trauma? And how might those of us aspiring to good and generative lives start to function like an ecosystem rather than a collection of separate, siloed projects? We are in kinship. How to make that real — and in making it real, make it more of an offering to the whole wide world?

Krista, Azita, and Janine spoke at the January 2024 gathering of visionaries, activists, and creatives where Krista also drew out Lyndsey Stonebridge and Lucas Johnson for the recent episode on Hannah Arendt. We’re excited to bring you back into that room.

Image by Bethany Birnie, © All Rights Reserved.

Guests

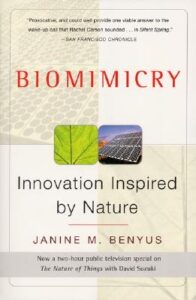

Janine Benyus is the author of several books, including Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature. She is the co-founder of the non-profit Biomimicry Institute. She also co-founded Biomimicry 3.8, a consulting and training company.

Azita Ardakani Walton is a philanthropist and social entrepreneur. She has pursued her work through nature's principles as a means to inform economics, social organizations, and design. She was the founder of the creative impact agency Lovesocial, and is currently in the pursuit of the relationship between inner life and outer ecology to meet the challenges of these times.

Transcript

Transcription by Alletta Cooper

Krista Tippett: It is true of the human condition that sometimes we grow by discovering something new. But as often, perhaps, we grow by grasping something that we’ve known forever, if only in our bodies — and know it for the first time with consciousness.

Nothing thrills me more for the future of our species than the learning that is underway about the deep nature of vitality in the natural world — how original vitality functions. It is strikingly antithetical to the ways we’ve organized our lives and societies and institutions — forms that now are failing us. And ever since I interviewed the biomimicry pioneer, Janine Benyus, for the first time in 2023, I’ve seen her way of seeing and designing as a key to the radical healing and remaking of the world that our generation in time is called to. Biomimicry, simply put, takes the natural world as teacher and mentor — emulating the genius with which it solves problems and performs what look like miracles in every second all around; running on sunlight, fitting form to function, recycling everything — relentlessly “creating conditions conducive to life.”

What follows here is a deeper delve from that first conversation, seeking precise guidance and wisdom for the intimate and civilizational challenges of this age. What does the natural world, for example, have to teach us about healing from trauma? And how might those of us who are striving to lead lives of healing and generativity in our places of life and work — how might we start to feel like an ecosystem rather than a collection of siloed projects? We are, like every living being, in kinship. How to make that real — and in making it real, make it more of an offering to the whole wide world?

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

I brought Janine Benyus together in conversation with Azita Ardakani Walton, who has been a student of biomimicry and an innovative practitioner of it. The three of us spoke at a gathering of visionaries, activists, and creatives in January 2024. And I’m excited to bring you into that room to think and learn alongside us.

[applause]

Tippett: So, what I want to do this morning is just lay a foundation so there’s a grasp of what we’re talking about. And then really go to this question: What might this have to do with the way we structure our lives, our work, our institutions, our society?

Janine, as we’ll get into a little bit, teaches and consults with all kinds of projects and organizations, including major corporations. Did you tell me that Microsoft has a Chief Biomimicry Officer?

Janine Benyus: Yes.

Tippett: Yeah. We don’t know this. This is happening. [laughter] This parallel universe is actually getting kind of official. She’s co-founder of a nonprofit, the Biomimicry Institute, and Biomimicry 3.8, which is a B Corp consultancy. She is precisely the kind of person I’ve always sought out for On Being who is working quietly and generously, and with humility and genius, below the radar, which is broken.

And I am thrilled to have up here with us Azita Ardakani Walton, who is the person who introduced me to Janine’s work. We got into, immediately, one of the most thrilling conversations and friendships that I’ve had in my life, and a shared sense of mission that has also shifted the way I walk through the world and what I’m reading, what I’m seeing, and what I’m looking for. And she has been in a longer ongoing conversation with Janine; the two of them finding all kinds of practical touch points and surfacing big dreams. Then I was able to be together with the two of them last summer to be part of this cumulative exploration.

It is also true of Azita that she is a powerful person of humility. She’s kind of content these days to be below the radar, below the broken radar, I think. But, in her earlier life, which wasn’t that long ago, she was a Forbes “30 under 30.” She has a background in sociology. She founded a very successful impact-driven creative agency. How old were you when you founded that?

Azita Ardakani Walton: 21.

Tippett: 21. Okay. [laughter] And spent a decade working with leaders in developing strategic campaigns across issues such as the global clean water crisis and human rights, and humane technology, and environmental conservation.

I also want to say, Azita, you were a child of war and of exile. That also shapes you and your absolute connection to life, to the fullness and complexity of reality, and now she’s working with biomimicry as a philanthropist.

Azita will sometimes say to me, we’ve had conversations about organizational development or, I don’t know, project work. And she’ll say, “What would be a biomimetic response to that?” [laughs] And that’s such an interesting question to walk around with, and I’m not sure that I have it in me to always think that through in such a sophisticated way. So we’re going to have this conversation and perhaps start thinking that way a little bit together.

I’d love to hear about, so you — I’d love to hear a little bit about how the conversation between the two of you started. So you, I think you reached out to Janine then, right?

Walton: Katherine Collins, who’s here…

Tippett: And Katherine Collins, who’s here.

Walton: …introduced us.

Tippett: And I hope Katherine will talk after the… There you are.

Benyus: Yeah.

Tippett: But you reached out to Katherine because you were both in investing. Right?

Benyus: And Katherine had taken the two-year course like Azita has and went on to write The Nature of Investing.

Tippett: Yeah, yeah.

Walton: It was wild. So I thought this concept of natural principles guiding a more feminine, circular ethic of investing, and I wrote it all out and I began it. It was called “Honeycomb.” And then as I was researching, I found Honeybee Capital and I was like, “Oh shit.” And I reached out with a bow of humility and embarrassment, and also remembering excitement because in physics they say there’s these dual discovery moments where in two totally different places, the same download, so to say, can appear.

Tippett: Yeah, yeah.

Walton: And I reached out waiting for a cease and desist or something of copying in some — And Katherine met me with this, I think your email said, “Hooray. There’s more of us. You have to meet Janine.” And so we reached out to Janine and she said, “Oh, hooray. Come to…” [laughter]

Benyus: “Come on out to Montana.”

Walton: “Come on out to Montana.” And a week later flew out to Montana. And yes, we spent some time at a table brainstorming and heartstorming, and then we went into the forest. And walking with Janine is an exceptional experience in nature. And just that expanse, it was just so reorienting. And then she cut me under her wing, and we’ve been conspiring ever since.

Tippett: Yeah.

Benyus: My gosh. Yeah. And the thing is that her investment thesis was a list of what we call “life’s principles,” things that all organisms have in common. And that’s how you were choosing — that’s how she was doing her business, based on does it meet these principles, living principles of emergence, of adaptability? I forget what they were. So yeah, you had all — that was already guiding you and you were just happy to say, to find another group of people who were being guided by [whispers] the real world, the real world.

Tippett: Yeah, the real world. [laughter] It’s not what I learned was the real world. I mean, my father actually used to use that phrase: “the real world.” This is not what he meant.

[laughter]

Okay. So here we are. So the deepest level of biomimicry, I get this Janine, from your writing, is “the mimicking of natural ecosystems.” And I think you and I, this summer, I think I started, I wandered into this with you. I love to use this language of: what if we started — we, all of us with our separate projects and our separate funding and our institutions, the way we’ve known how to build them — what if we started to act like an ecosystem? And I think I asked you, is that even an intelligent question? You did say to me that every ecosystem has to start at some point. So just walk us into, what do we know about how ecosystems start? And I obviously realize it’s also complicated when you are starting with the levels and the systematization of separation that we’re dealing with, but still.

Benyus: Well, actually, there’s good news in it, to tell you the truth. So there’s this thing called succession. If you open up a field, say…

Tippett: You’re not talking, it’s not the TV show?

Benyus: No, it’s so not that.

Tippett: No, that’s the real world I learned about.

[laughter]

Benyus: No, no, this is the real world, capital R.

Tippett: Okay.

Benyus: So say a landslide has come through or there’s been a clear cut or whatever. So there’s this beautiful succession that happens where at first, the first ones coming, come in the type one species, and we call them weed species. They’re annual plants and they come in and what they’re doing is basically spreading out as quickly as they can — cover that ground. Because healing, the first thing is, don’t let the good stuff go. And that’s why you scar over so quickly. There’s that little, don’t let the good stuff leak out, all those nutrients that are there. So that’s their job. They come in and then they put all of their energy into creating pretty small bodies and seeds, not a lot of roots. And those seeds then blow off to the next opening that needs healing.

And what they’ve done though, is started to soften up the soil, started to put nutrients in, and the next group is the shrubs and the berries. And they start to put down roots. They’re going to stay for a while, and then they start what’s called facilitating. They start shading little seedlings, keeping wind away, creating. There’s a windward and a leeward, so some species that are a little more tender can get started. There’s this whole chaperoning and facilitation that happens. And then in the shade and the windshields of these trees, of these shrubs, little seedlings start and then those seedlings become the overstory that we know about. So literally it is a progression of making way, making things more and more fertile for the next cohort to come. So there’s this incredible generosity and everybody’s got their place.

But what’s really interesting, the thing that I’ve been thinking a lot about, and you do this so beautifully, bringing all these different circles of different places that we’re working in the world, and we may not know each other, but you’re bringing us all together to know each other’s work.

Well, that also happens because the way I just described it to you, it actually happens, like if a rain forest gets cut down, the way it starts is that there might be a stick, or a little rise and a bird lands — This is how it really starts. This is how the seeds of the weed seeds get in there — and it poops something out. And then that seed takes over and starts to become the facilitor of this succession in a circle, in a sort of circular way. And it’s also happening over there in the field, and it’s happening over there in the field, and in between, there are empty spaces.

And when people ask me, how are things going? I’m like, well, I think the circles of healing are starting to grow and they’re starting to grow towards each other. And if we were to reach out our hand in the dark at this point, we might find another hand.

And that’s actually what happens. In fact, I’m going to go for my next book, I’m going to interview somebody here in Santa Cruz who does something called nucleated forestry, where we have so much healing to do on this planet and what we do, the industrial way to do that would be to put — this is what we have done — to put trees in a row, like corn fields. That’s not the way regeneration happens. It happens in these little islands that then spread out and meet.

So now what they’re doing is they’re nucleating the forest. And they can do it with 16, it’s only 16 percent of the field. So when we talk about all the healing we have to do, it’s really nice that you don’t have to cover the whole field like you do in a cornfield. What you do is you put welcoming islands. So you put a few…

Tippett: Love that.

Benyus: …you put a wild diversity of species together because they all need each other. And then you put a post — you could do this in your fields — and that post is where a bird will land. So you welcome in the ones that are going to disperse all of the diversity and you do it the way nature does, in these islands, and then they will coalesce. And maybe that’s what we’re — when we do these gatherings and we hear each other’s work. Think of it that way.

Tippett: Wonderful. So I know you’re working on this new book and I asked you, I wanted to see it and you said “It’s not ready,” so okay. [laughs] But you did make available the chapter titles, right?

Benyus: Yes.

Tippett: And all the chapter titles are questions. And of course, we know we love questions at On Being. So we can’t go through all of them, but it’s a very intriguing list. I mean, I’ll read them. “How does Nature heal from trauma? How does Nature grow, scale, and rightsize? How does Nature network and shape community? How does Nature circulate and reincarnate materials? How does Nature learn, adapt, and evolve? How does Nature self-organize for collective action? How does Nature regenerate abundance not just for self, but for all?” So now we wish we could talk about all these for an hour. [laughter] How does nature heal from trauma? That feels very resonant for us right now in this world and in this room, I’m sure. What do we know about how nature heals from trauma? Maybe you started to just tell us, right?

Benyus: I did, I did. I started to tell you. Yeah. So what I’m doing in this book is trying to look for, as Kenny would say, original instructions. It’s a book about nature’s universals. So it’s in all the wild diversity, amoeba through zebra across the tree of life. What do organisms have in common? What do we have in common? Because I’ve been struck by the things we do have in common. And so I’m looking at, for instance, in the healing chapter or the growing chapter, I’m looking at, cut your finger; how does that heal? Mount St. Helens blows up. How does that heal? And are there, across scales, are there similar patterns?

And it is such an amazing book to research looking at all those scales. And there are patterns, as Bateson would say, “the pattern which connects.” There definitely are patterns, which is really good. Once we say to ourselves that we’re going to emulate those patterns, we’re going to become part of the — we already are part of the pattern. We’re just young. Once we start to knit ourselves together as a society the way life does. And that’s how it heals, by the way.

Tippett: Knitting together?

Benyus: Knitting together. Okay, so let’s say Mount St. Helens blows up. Actually, the studies on Mount St. Helens, the first organism that came in and that incredible ash field was a ballooning spider. So spiders will put out — when they’re very, very tiny — they’ll put out a long, long, long, long, long silk thread and then let go of wherever they are. And the silk thread gets picked up by the wind and they get carried, way up into the atmosphere. They go on these giant journeys. There’s a children’s book in this, for sure. [laughter] That was the first organism they found, was a spider. And that spider built a web, probably out of its balloon, and then that attracted other insects that came by. And next thing you know, all of this organic matter started and started to grow. And so did the seed banks. Things came up that were already in the seed bank.

So the way life heals, if it’s healthy, those ecosystems, they heal because they have a memory of what they used to be. And that’s in the seed bank. And those seeds come together and they start to grow and help each other, like I was talking about. And what they’re doing at first is just holding down those nutrients, right? They’re sealing the break.

And what’s really interesting is that, one of the patterns — I mean I could go on all day — but one of the patterns I find interesting is that when you cut yourself literally — you know murmuration of starlings and flocking — your cells, some of your immune cells flock and they come to the site of the cut like a flock of birds. And they get on either side of the cut and they pull the skin together as it’s being, as the fibroids are being formed. There’s a first thing, and that’s similar to what happens in an ecosystem. The first group comes out — the first group of seeds that get there — and they start holding it down. Now, they may not be the only ones there for a while — I mean, they may not be the ultimate ones there, but that’s their job, is the healing quickly.

Same thing with you get a little mini scar and then that mini scar gets completely broken down to finish it off with the end, for the end. And what that means is that your final thing that’s done slowly, if it’s a big cut, it can take a year. But at first, you get this covering, which is just a temporary covering. That’s a completely different process. And I see that now.

I live in western Montana with wildfires, and I really like walking. I took you on a healing canyon that had burnt over. And it’s amazing, you watch every bit of that soil is covered. And then if you come back 10 years later, it won’t be the same plants. Because they were the first scar-cover.

Tippett: Right. Wow.

Benyus: Yeah.

Tippett: Gosh.

Benyus: Yes. But there’s so much attention to healing. Everybody just stops everything they’re doing and rushes to the side of the wound. Whereas we tend to, as you and I when we were talking, we tend to look away instead of rushing into it.

Tippett: What was that conversation you two had?

Walton: Just that, what we’re talking about is a natural field of organisms that’s sole intention is to work together. And the collective memory of an ecosystem isn’t lost in the more-than-human world. And there’s no self-interest or man-made structure that says: this is the ecosystem you must work in. And so watching and seeing how that happens to me, is both so life-giving — and we’ve talked about this, that we do have in that cellular memory a way to find each other, to reach out, to do this work, these islands of fertility that it doesn’t require — I think one of the colonized ways of thinking is in structures, but these are all very new systems. And Janine and I often talk about even in the natural world, if there’s a strategy — first of all, there’s no strategies actually. There’s responses. So it’s not a “set it and forget it,” it’s not this worked and now we just keep — there is replication of things that work until they don’t.

And kind of going back to the beginning, I’m so interested in why this doesn’t take as much, and it’s, I think, partially ego, partially, we’re so calcified inside our unconscious and conscious agreements of our human structures and systems, that it doesn’t allow for the flexibility and the capacity that we have because we’re each nucleated in our own ways. And even, and especially right now, one of my biggest concerns in fields of healing, people that are offering that in their field of work, it’s still inside systems that are competitive for funding. And there’s a lot of inward hurt that without that reconciliation and that work together to create the coherence to actually find one another in these fields of fertility, sadly, we can keep replicating some of those things.

And so, in the natural world, there might be a strategy or a response type that works for a million years. But million year day two, if it doesn’t work anymore, i.e. doesn’t serve the collective vitality, it will respond otherwise. And it’s not attached to the thing that used to work before.

So I think that’s so important to think about that geological time because GDP as a concept was created in the 1930s. I mean, this is recent stuff, and it can feel so set and it can — capitalism and systemized colonization and racism and the hatred and the war and the way that we work against each other and the way we’re approaching energy — that can feel like, oh, we’re too far gone. We’re going to hit all these brinks but pulling back and being like, these were all made up things and we made up this magic trick, then we all signed up for it. We can sign up for something else. And time is on our side as a multi-species reality.

[music: “Woodbird Theme” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: So I was recently in a room of a philanthropists and from many, many different fields. And I don’t know if this is true for all of you, but I feel like everyone in every discipline right now is in an existential crisis and wanting and trying to reimagine because the forms we have don’t work, have stopped working. And then we end up investing so much labor and creativity and time and energy into just keeping the thing together. And we are not focusing all that energy and creativity on the work and on being of service.

But in this room, I think I was saying things like talking about emergence like I did last night. And I think I may even have said that writing grant reports is often such a creative writing exercise when you get asked, “What will be the fifteen-year impact,” and we’re all making it up. [laughter] And also that’s a waste of time. And yet the reasonable response came back that, well, we do need metrics, we need accountability, right? And somebody said she really liked this idea of emergence, but she really likes strategizing.

And also — well, let’s just lump these things together. The notion of competition that is, well, first of all, it’s like it’s an American, we idolize, we have turned competition into an idol. I think my understanding from you and others is that of course there is competition, there are predators and there is hierarchy of a sorts in the natural world, but it is all held in a framework of cooperation and reciprocity, which is different.

But anyway, so I would love just for the two of you to kind of think about these things that we hold dear as Americans and how does the natural world, how would the natural world try to teach us now? Because we know that these things actually aren’t working for us anymore and they aren’t even working for our institutions that were made in their image.

Benyus: I mean, I think part of my work is to look into the natural world with clear eyes and try to describe what is happening, really happening. You cannot separate science and what science is telling us, because science is our best approximation of what we think is going on out there right now. We see through a glass darkly, but we keep on trying, Western science. And then people, Indigenous science, they’ve been also trying to understand their ecosystems that they’re a part of for tens of thousands of years. And it is not culturally neutral, science, at all.

Tippett: Right.

Benyus: And so I get this conversation a lot about competition because everybody just absolutely assumes that competition — and so did ecology for so long — competition was what, if you ask: how do ecosystems form? Why do you look out there and see that kind of ecosystem here? There was this huge debate. It was the biggest debate in ecology at the turn of the century, and this is why we were told, and we still believe in our economics, that competition is the way of the natural world. It is a part of the natural world. It’s actually a very small part of the natural world to tell you the truth. Because if you do head-to-head competition, if you fly into a Galapagos Island and you’re two seabirds, shorebirds, and you both go after the same clam, over, you are not going to want to do head-to-head competition. Evolution actually makes you coexist. One’ll have a longer beak and get to something down there.

Organisms don’t want to compete. It’s messy, it’s bloody, it leads to death. They don’t want to compete head-to-head. They compete with mates. But really, most of life is this cooperation that I was talking about, this facilitation.

I’ve been studying this for my book, too. There was a historic thing that happened. These two guys, Frederic Clements and Henry Gleason in the early 1900s when there were hardly any ecologists. The big question on their lips was, how do ecosystems start? Clements looked and he saw a mutual aid society out there. He saw that cooperative society that I had been talking about. And then Gleason said, “Nope, they’re just responding to climate and soil. They spread themselves out on the landscape because they’re in head-to-head competition.” And this is our gardening paradigm. You’ve got to weed out so everybody’s got their own. The competition is deep in how we manage lands. And anyway, it was a question. It was an open question. And for almost 50 years we followed Clements in the science.

Tippett: Yeah.

Benyus: And we said it is a mutual aid society and we study cooperation and mutualisms and symbiosis, and we were studying mycorrhizal fungi back then. This is from about 1914. And then I looked into the literature and I said, “Where did this change?” Because when I grew up, we were all studying competition. We were told that’s how these systems form and that’s Gleason. How did that happen? And I found the typewritten reports from the historical meetings, the scientific meetings, when you could get 25 ecologists with cigars — and that’s all there were — in the country in a room. And I found out that one of Gleason’s protégés stood up and started to say: I think it’s individualism, not mutual aid. I think Clements is wrong. And this whole thing happened, it took about 12 years, and then competition was in and cooperation was out, meaning you couldn’t get into graduate school if you were studying—

Tippett: And that’s the way we do it. There was a winner and there was a loser.

Benyus: Yep, there was. The thing was it was 1947, Truman Doctrine, and the beginning of the Cold War. It was the same year. And communism was a third rail even when talking about plants. [laughs] Seriously. And then we started, and about 20 years ago, thank goodness, we started to study cooperation again. But we had a 50-year, almost 50-year gap when we have been studying competition instead.

Walton: Krista, can I add a little? Something Janine and I talk about a lot is — and to the strategizing soul that came to you last night…

Tippett: Yeah. I want to hear what you think about that.

Walton: …because it is really confusing. I think a lot of these ideas land deeply amongst the self-selected group. It’s like, “Yeah.” And then you go out into the world and you do have the grant to write or whatever the thing is, and needing to orient around some semblance of a strategy or a theory of change. And I just want to uplift two of the systems we’ve talked a lot about, the autonomic and the adaptive system; that in the natural world and in our own bodies, there is a command control function that’s like, “Okay, I remember the past. I think I know where I’m going to the future.” And it’s humming along. And there’s the adaptive system that’s constantly sensing. And in an organization, the meta-system right now is for the most part command control and production-oriented. And production oriented, even in the way we strategize and we do the good work in the world and measure the good work in the world that we’re trying to do.

But making space for the adaptive function and the people that are just there to be the sensors and the antenna signals so that everyone doesn’t get sucked into the inertia. Because usually what happens is there’s this adaptive explosive moment of creativity when the idea is born or the ideas are born and then it gets co-opted into the command control system as opposed to it being this kind of orchestra or song that works together. And there’s people that their superpower, their innate superpower, is strategy or an Excel spreadsheet. And I think it’s important not to make those things bad or wrong, that we’re all going to be in this thing because we actually really need both to have our even nervous systems regulated in the workplace.

And I think about when something happens — so say the whatever trauma occurs into a landscape — the eagles aren’t like, “Oh, the whales need us. I’m going to go be a whale to help the whales.” The eagles are like, “Everyone is very much in the sovereignty of their intelligence. What is the best and highest use of what only I can do?” And that’s really important right now. And if the highest and best use of your gifts and your kind of cosmic task falls a little bit more into the command control function, that’s okay. But you won’t even know the fullness of it unless you have your adaptive counterpart with you. And so when I think about organizations and harmony, I do like invoking kind of both.

Tippett: I love that. So it would be kind of building in an adaptive sensibility that would be part of the whole — I think this is a reason I’m really grateful for language that I have actually from spiritual tradition of “discernment.” And in our workplace, I’m always talking about, we’re always in “discernment” and that means that even when what we’re doing is good, we have to be reflecting on it and responding to what the world is asking of us, which may be very different. In these last years I feel like every six months it feels like it keeps shifting, and how to be of service and how most distinctly to be of service. So you’re talking about creating, yeah, we would turn it into a division with a vice president. Vice President of Adaptation. [laughs] I just think that’s really interesting. Maybe we can talk about that. So we have 10 more minutes and then we’re going to take a break and then we’ll come back and then we can keep going.

I wanted to get at some words, values, human experiences that I hear rising up, especially for people who are working as hard as they can to be attuned to what is my service to the world right now. And in new generations, I’m hearing this beautiful insistence on — because this is the work for the rest of our lifetimes, what are our sources of resilience? And that as much as we know we have to heal or fight or build, if we don’t know what we love, if we don’t know what joy powers us if we don’t know to reach for that again and again, that’s part of the equation of vitality and even of changing the world. And so I wonder, language like beauty, you and I did talk about this last time. You said: The whole time we are evolving, beauty has always been a signal of the good.

Benyus: Yeah.

Tippett: I think of in Islam, there’s this notion of beauty as a core moral value. I love that. In adrienne maree brown: pleasure activism. So what are the corollaries in the natural world to pleasure and joy and love?

Benyus: Yeah, beauty is the signal of the good. I mean this drawing, we’re not the only ones drawn to beauty, to what we now see as beautiful. Organisms are constantly — Evolutionary psychologists say that the reason, especially women, love flowers and why is because we used to walk through the jungle and look for flowers. And that meant two weeks later there was juicy fruit. Flowers were food. So we’ve been tuned to go, “Ah!” And down deep, it’s the pleasure of the flower is the promise of the sweetness of the fruit, which is what’s good for us. So that idea of beauty was the signal of the good. And now when I work with people who make things and beautiful lust traps, products that I want to hold in my hand and go, “Oh God, I love this. I love this iPhone” and it’s leaching chemicals into my hands. That’s not juicy fruit. That is a biological trespass. I work with designers. I say, “Please, you have to recouple the idea that beauty is the signal of the good because we’re tuned to that. We’re susceptible to that and give us good with beauty.”

Tippett: I want to say there are some people in this room who design phones…

Benyus: Yes.

Tippett: …and who are some of the most ethical and people who admire this too and are designing in a spirit of responsibility and also a part of a much larger supply chain and organizations. So I think even just all of us are part of this conversation.

Benyus: They know it. I mean, there’s so many designers. So people who make our world within these big corporations and in small corporations, they’re trying in so many ways to recouple beauty as the signal of the good.

Tippett: And what about pleasure and joy? Let’s get to pleasure.

Benyus: Pleasure and joy. I mean, have you ever seen an otter, like an otter family? [laughter] Otter families. I mean they do it. They play because they can because they’re so good at what they do. Or I remember the first time I was in the Galapagos, I went awkwardly with my flippers and stuff into the water and this amazing creature came up to me and it was a sea lion, came right up to my thing and blew bubbles in my face. [laughter] That’s play. And then went away and then looked back at me like, “Chase me.” And I was like, okay. Awkwardly over trying to help me play.

Walton: Also, maybe don’t chase sea lions generally.

[laughter]

Benyus: No, don’t do that at home. Don’t do that at home. But anyway, yeah, no, they’re playing and they play the night moves. They’re doing the play that will eventually be like young ones, eventually, that will help them, the bear catch the salmon. But they do the moves and they do it in this stylistic play way. There’s a lot of joy. There’s a lot of joy in the natural world. And the thing is that what is valued in the natural world, the rest of the natural world, and it needs to be in ours as well, is the continuity of life.

Tippett: The what?

Walton: Continuity of life.

Benyus: The continuity of life. So it’s “I want to thrive, yes, and I want my offspring to thrive.” But everything that natural selection has chosen winds up helping the generations, tens and thousands and hundreds of thousands of years to come. Because when organisms — the organisms that are chosen that are here with us on Earth, have figured out a way to take care of the place that’s going to take care of their offspring in those far, far times. And everything is towards life. So come to our house in the springtime, it’s incredible. We live between two ponds and they’ve come back now and you have to wear eye guards and a hard hat because there are birds flying and mating and breeding, and they don’t care if you’re in the way. [laughter] If you get in between two swallows or trying to get to each other to do the continuity of life, you’ve got to duck, [laughter] so to speak. You really have to — Like, life is so fecund. [laughter]

Tippett: Right.

Benyus: So yeah. Are they having fun out there? Too much fun, in the service of life.

[laughter]

Tippett: Okay, wonderful. So this will be my last word. We’ll wind down now. So Azita, you interviewed Janine at a business-y thing, 2023?

Benyus: Yeah.

Walton: A business-y thing. [laughs]

Tippett: So when I just say Azita was worried about being up here and would she have anything to say. So this is just one of your questions: “The pandemic showed us many things. One was the reminder that we are absolutely biological organisms and nature can press upon our bodies and make itself known at any time. And that over-infrastructured, singular-source supply chains can’t respond to uncertain times.” Resilience, as a whole, principles to create resilience, diversity of businesses locally, vitality locally, attuned regional market sheds, understand its gifts to place a superpower in that. I think those are notes, but we get it. So she said, “Let’s end on phenotypic plasticity.”

[laughter]

So let’s end on phenotypic plasticity. What is phenotypic plasticity?

Benyus: Do you want me to?

Walton: Yeah.

Benyus: Okay. All right. Best new thing in the world, as Rachel Maddow would say. phenotypic plasticity. So it turns out that life has many more tricks up its sleeve. And in many more responses — thank goodness — than we thought that life had. And in a climate-changed world, we’re seeing organisms begin to stretch into behavioral and physiological repertoires that we didn’t know they could do. Now they are afraid, for sure, and they are under pressure, for sure. But as a biologist, like Aldo Leopold said, to have an ecological education is to live “alone in a world of wounds.” I work with a lot of scientists who are traumatized. So phenotypic plasticity is our newest, greatest thing. So what it is that we used to think that the genome was a sort of a one-to-one thing. You had a gene for this, it would create this kind of a protein. That’s the way it was. So it was much more of a coding — we look to our machines – it was much more of a software, it was like a machine metaphor.

Now they’re thinking of the genome as a piano with a lot of keys. And depending on the habitat conditions, and if they change, for instance, if they get drier or hotter or wetter as they’re getting, the organism is able to turn on and off a lot of other genes that we didn’t think they could in different cords, say, that we didn’t think they could. So for instance, if it gets warm really early in the spring and a tree like an aspen will put on leaves, we thought that was it. They put on those leaves and then we would be really upset when the freeze would come and all the leaves would fall off and we’d think, oh my gosh, that’s it. That’s it for the aspen this year. And then you go outside and they’re putting on a second growth of leaves. Literally that’s happening everywhere in the scientific community. It’s like we didn’t know they could do that. We didn’t know they could do that.

Now, that’s not to say that they can handle everything that we’re throwing at them. There will be a lot. Everybody’s moving. Everybody’s moving south to north, everybody’s moving from up to cool on mountains and they’re getting to places, there’s a lot of ecological disruption. There’s a lot of brand-new communities. Imagine going somewhere, you’re a flower and you move north and your pollinator doesn’t come with you. That’s what keeps me up at night.

And life is starting to knit together new communities, they’re finding new pollinators. We need to help that process. They are undergoing a lot. And they do have phenotypic plasticity. They have a plastic repertoire. It helps. If for instance, you know they’re moving through and you create corridors in your cities. If they’re coming up and all of a sudden they hit Philadelphia, they don’t have time to go around. Put corridors through, put them on your rooftops, put them — help them through. We need to set a banquet for these organisms to show us how it’s done until we get our CO2 levels down and we’ve pulled that down and we’ve started to cool that Earth down again, that global warming again.

In the meantime, we have to help them with the transition, but also know that they can stretch more than we thought. And so can we. Back to your point about we don’t have to live with this economic system we have, we actually can play different chords on our piano — our mental, our cultural piano.

Walton: And I would add to that, emergent phenomena aren’t just positive. Capitalism and this complex system, this world that we live in that is not serving us, is also an emergent phenomenon. So when you talk about the deep, caring person, engineer at the massive corporation, there’s so many people that are inside the emergent phenomenon that at this point it’s a superorganism, as some would say. But it’s really hard to jump into and change from the inside out. So just like we can have positive emergence, we are living amongst a different kind of emergence. It’s a bunch of inputs, and that’s what makes it so challenging. So I think, I just want to invite in the moral paradox that we’re in and that I myself live in as a newfound philanthropist, so to say — which does not happen in the natural world. There is no hoarding. But here we are. Here we are inside the emergence, we did not necessarily choose, creating islands of more hopefully coherent emergence to knit together in your words. And how do we do that and have inside us the capacity to hold that tension?

[music: “Grayback Thrush” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: After we took a break at the January 2024 Gathering where this conversation happened, we opened up to the room. But this was not a typical Q and A — it was a further deepening into the ideas Janine and Azita had offered and how they might be applied in many disciplines and lives. As a reminder, and as you’ll hear, there were people present from a range of disciplines and life experience. The back and forth was itself a practice of the ecosystem thinking and building we were there to explore. Everyone you’ll hear has also given their permission for us to broadcast their comments.

Jenn Brandel: Hi, I’m Jenn Brandel, and I’m flop-sweating with excitement to ask both of you questions from that conversation. Janine, thank you for giving me the language for what I do now in this room. I can just say: I’m a bird who shits on posts in various fields, so thank you for that.

[laughter]

And Azita I had a question for you about biomimicry within corporate structures, and is there a way in which when a group of us decide to organize towards some common goal, we don’t have to suddenly become a silo whose goal is to self-perpetuate in a C Corp or a B Corp or a 501(c), whatever. And have you seen ways in which people are able to collaborate like mycelium networks, like interstitium, like the folks in this room doing in a way that doesn’t compromise you into having to just protect yourself and instead to be generous and open with resources, especially when funding, whether through investment or nonprofit philanthropy, is designed to help an organization do something, not an ecosystem emerge to its highest potential?

Tippett: Can I just say Jenn wrote the most amazing article about the interstitium, which is a new organ, which has been discovered in the body even though it was visible to the naked eye, but it didn’t look like an organ. It was soft and flowy and I can’t do it justice, but it’s a beautiful — and it was in Orion, right?

Audience: What’s it called?

Brandel: The interstitium is the organ, and there’s a piece in Orion called “Invisible Landscapes.” And then…

Tippett: It’s so beautiful.

Brandel: …Radiolab, I did an episode with them that explores the science of it, and its implications for cancer and understanding eastern medicine, and all sorts of fun stuff.

Walton: I think you answered your own question.

Benyus: Beautiful.

Brandel: Oh, no.

[laughter]

Walton: No, I mean, and honestly, that is a very biomimetic thing, is the most alive thing that we work on is probably the biological intelligence that’s driving us to the next best step in our strategy organization. But the interstitium — is that how you — that connective tissue and that moist way of working and valuing the translational bridges in our organizations that have that kind of flexibility, I’ll invoke that artists are some of the best people that do that — poetry and to actually have design for interstitium to design for connection fascia and the character types or I don’t know, the archetypal way of working for those folks, it’s just the way they are as organisms. And they can’t work in command control or even fully adaptive. They need to be those connectors. And I think we just need to uplift different kinds of roles where they’re dedicated way of working interdisciplinary or through partnerships or whatever else is to see what’s most alive to connect at any given point. But they need to be given designated corridors.

When we talk about corridors, there’s also all sorts of roles that actually need to be created, an organizational structure to allow those flows to actually work. And I really believe in the power of artists to do that.

Benyus: That’s good.

Joy Mayer: Hello. Hello. My name is Joy Mayer, and I have a question that’s on the mind of a few of us after that incredible conversation. How does the sharing of information contribute to collective vitality in the natural world? And how do organisms separate helpful signals from noise?

[audience murmurs]

Benyus: Oh, my.

Walton: I personally believe the noise pollution, both physically noise pollution, as well as our inner noise pollution, is probably one of the single biggest threats to our humanity. And to be able to quiet ourselves enough in whatever practice, and then in the fields of discovery of where we work or where we live, find quietude, so that the signal and antenna can even meet is, to me, the front line of the work. Because if we can’t quiet ourselves, getting the instructions, knowing how to meet each other is actually impossible. I would start there.

Tippett: Azita and I talk a lot about what spiritual means and this is such a good example. These are parts of us and ways of being that are actually pragmatically essential. There’s nothing fluffy about this. This is about core vitality.

Benyus: Yeah, and that’s the first step in biomimicry, is quieting human cleverness. We’re very noisy in our own brains. Gosh, there’s so much to say about communication in the natural world. It is just know that senses, which are senses that pick up all kinds of communication signals are the largest energy expenditure in the budget of an organism. Scientists have looked for years and said, “oh my gosh, your eyes are so big. And oh, it’s connected to a brain. And that’s so big and there’s so much energy going into it.”

It is essential for these ecosystems to maintain their vitality. They are in constant conversation. All these organisms with one another, usually chemical signals, and they’re traveling fast and they’re traveling instantly. A caterpillar eats one of those needles on the redwood tree and that redwood tree needs to beef up its defenses. And within minutes, all of its needles have changed their chemistry to be less palatable. And volatile organics have gone out into the forest so that all the trees around are now sending out volatiles, right? They are definitely — they’re like a chorus that repeats over and over again, all these communication signals. It’s huge. So, communication in the natural world is three parts — otherwise, it’s not communication, which is, there’s the signal, and then there’s the translation of the signal that happens, called transduction, into meaning. And then, the third part is action.

So, communication is actually just not the signal, it’s the response. Otherwise, it’s not necessarily considered communication because it didn’t lead to anything, which is a really helpful thing for me to remember, that it’s a circuit, right? It’s not just me saying something out loud and then having nothing happen. It’s part of what that idea has driven my work in terms of not just putting a book out there necessarily, but actually saying, “Okay, now how do we practice it? How do we make it happen in the world? Is there an action at the end of that?”

The other thing is that life really depends on signals blinking, clear and true. So, there is some deception in the natural world, but very little, very little. Cheaters, those who deceive with information — this is what pains me the most right now about the fog of disinformation is how dangerous that is. In the natural world, you will not find much deception in signals, not for long.

Walton: I want to add about deception, and a few folks kind of brought up during the break, it’s not all hunky dory. There’s parasites, there’s some what looks like vicious and anti, against each other behavior in the natural world. And I thought to that, yes. But there is a central organism, planetary agreement that while there is dynamic non-equilibrium, it stays within net balance. So, inside things, of course, tensions and competition and misinformation happen, but there’s a mutualistic for the survival, net survival, of the larger life for us to go on will stay within certain boundary lanes and things will be corrected.

Benyus: Yeah.

Tippett: Okay.

Benyus: Feedback loops.

Rabbi Joshua Lesser: Hi, I’m Joshua Lesser. As I listened to you, there’s both a poetry and a spirituality that really feels is integrated into the kinds of awareness, insight, and attunement that you have in looking at the world and connecting with nature. And in the work that I do in sitting with people, often in discernment, that noise that we’ve been talking about, that — we want to be distracted for a variety of reasons. But most profoundly, I feel it’s often because of touching into the pain and the despair pieces of what it means to be alive.

And so, I was wondering, just, I hope this isn’t a too vulnerable question, but if there’s a way that you might help us understand a little bit about what your practice is like in order to be the scientists and to be the visionaries that you are, I think it’s helpful for us who are looking at how to pay attention in a different way or to look at things with the kind of wonder and curiosity that’s possible. I’m sure you get distracted at times. I’m sure that there’s the pain in the world that you touch into. And so, if you’d be willing, I’d love to hear about what are your practices that ground you when hopelessness feels it’s right at the door?

Walton: Well, I have the great benefit of being, when I was an embryo during the war, my mom went to Sufi classes, so I’m the beneficiary of atmospheric mysticism and to have a cellular experience of the more-than. And then, during the war, we were so — she took me away to a very natural place. And so, even though there was the stories as my brain came online of scary people, scary things, lack of safety, lack of food, all the things that make you scared as a being, there was also this innate remembering of something larger, holding it all. And even if someone doesn’t have a pathway to — I’m not an active Sufi in my own way, but the felt experience of the expanse is something I know. And so, often, I just, when it’s too much, when it’s just too much, I just put my little body on the earth. [crying] And if you can be naked when you do that, I highly recommend it.

[laughter]

Benyus: Yes. Yeah. Krista?

Tippett: No, I just want to hear from you all. Janine, you don’t have to, do you want to say anything? You don’t have to. You can just cry.

Benyus: Well, I cry a lot. I do cry a lot. It’s good. The radical empathy experiments, what really, and ever since I was a little girl, what has soothed me is to go to a place that I know very, very well in the natural world. And it was this field when I was growing up called Sir Morton Rump Field. I called it, sir. I had some Elizabethan poetry in me then. And so, Sir Morton Rump Field with a P, Rump Field, I would go there and I would know everything about these organisms. I would spend all summer out there, literally all summer, just getting to know. So, the radical empathy of going and saying, how are you doing this morning? What are you doing this morning? And getting to know a place really, really well is super soothing for me. Getting to know a place as a community and as a neighborhood and the organisms in that place, and then sitting down, girl in the grass watching ants. I mean, watch how competent they are. They know what’s worth doing. They’re not highly stressed. Realize that this species, we do tend to get into our own, our minds. It’s an emergency of our own making. But there’s a calmness and a confidence that I always return to when watching community unfold in the natural world. And whenever I need to do something, like if I need to begin anew or begin something new, I’ll go to a place where spring is happening or where there’s a new opening in a forest and look at newness and how it happens. Or if I need to heal, I’ll go to an old fire scar. I literally will go and look at, find other beings who are doing what I’m doing, and see what they’ll tell me.

Tippett: There was a question that came in from an introvert, related to this: “I have been captured by the idea of people like Bayo Akomolafe that to change we must first be able to grieve.” And the question is, “What can the natural world teach us about grief and its relationship to change? What is the corollary? How does that strike you?”

Walton: I can offer a little something there just around metabolization. Grief is like a crest, a wave, something that asks of you to pay attention to it because it’s a flood of energy ultimately. And it takes the shape of grief based on the input that had arrived there and it demands of us to metabolize it. And so, I see it as like energetic metabolization ahead of doing what you think you need to do next. You have to sit with the energy that’s demanding your attention.

Tippett: And yet we can resist doing it. And then, it is still with us. It’s still shaping us.

Walton: And if you don’t metabolize well, you know what indigestion feels like, so —

Tippett: Right.

Benyus: That’s right. Yeah. I mean life, it’s amazing. Life is just so full of vitality and so much on and being alive. And then it’s not. And then, the pattern breaks down. It’s like what is the difference between something that is alive and something that — it seems that that holding onto life, there’s also a once it’s gone, a letting go. And the letting go is — we think of it as a body breaks down. But it doesn’t really, I mean, not for long.

So, what happens is a log — a tree falls, and then the material in the log, like a bacterial lands or fungus lands, and you think of the log as breaking down. It is no longer, but it breaks down, and then, immediately that material becomes fungus. And then a mouse comes along and it’s the end of the fungus, but that material, that’s where the reincarnation comes in. The material becomes mouse, and then a hawk comes along, and the material, that material, that mouse becomes hawk. And then the hawk poops and — there’s this circulation, which has to do with you break down, it’s called catabolism. Even as we eat what we ate for a break or whatever, it’s catabolism, think catastrophe, it breaks down. But then immediately those materials, there’s something in your body going, “Oh, great, look what we have now to work with.” And it gets anabolized — metabolism, anabolism, up into a new form. So, the grief is brief because transformation happens almost right away. It gets transformed.

Walton: Grief is a digestive enzyme.

[laughter]

Benyus: It is.

Tippett: I don’t know, we probably just have time for one or two more quickly.

Rev. angel Kyodo williams: Somewhere along the line, Krista, you said, we are all in existential crisis. And I think that when we reorient as to where we are located in that process, rather than we’re at the end of the breakdown, that we are making way that we are clearing for something that comes anew. And the question for me that arises in there simultaneously is when you were speaking, Janine, about the way that there’s a first layer in the scarring and it gives way, right? It’s sort of creating the foundation for the possibility of the things that are going to grow, but it’s not there anymore. And you said that very specifically. It’s like it doesn’t stay there. It goes on to seed. And I think a lot about our organizations and our institutions and the way we re-individualize, we hyper-individualize.

And so that when we have to have loss within our own organizations, family systems, whatever, institutions, we sort of treat it like those things are like the log. They’re dying and we feel some terrible thing about we’re losing people. But it occurs to me that that’s only if we are in this isolationist sense. It’s like what is happening, that seeding, that first layer is not there in our institutions, but it is gone on to. And so, we can more readily prepare ourselves to lose in that sense, in the best sense, to lose, to give way to metabolize, to the situations, the people, the conditions that are — it’s not that they don’t serve in some broader part of the ecosystem. It just isn’t right-aligned for that island of growth and healing that has to occur. And so, we would then be less inclined to keep recreating and holding onto things that are no longer fit for that millionth and year and day two that it doesn’t fit anymore because we are so busy recreating the habits of things that are not working for us. Not working for us but very much attached to a kind of love and attachment to the people and familiarity that we have. But I think that we may be doing a disservice under the guise of love and not allowing healing and renewal of what needs to come and what needs to emerge so that we can have that catharsis and not see it as crisis but love.

[applause]

Walton: Yeah. Get up here.

Tippett: Okay. I think maybe we let you have that last word in the room. And I actually want to share as I’ve been in conversation with people like Janine, and Azita, and adrienne. And I started keeping this list of words, so ways of being that exist, ways of acting that are in the natural world. And it’s such a different list, to this point than, even how we collaborate and partner. And so, I kind of keep this list in front of me from time to time. And it’s a creative, it’s a source of kind of creative thinking. So, I’m going to give you these words. What would it be like if we did this with our institutions? And literally, I don’t know. It’s an interesting question.

Branching, braiding, interweaving, entanglement, underground life support, interactivity, collective scaling, composting, regenerating — dying is always in there with vitality. Critical yeast and spider’s web — those come from John Paul. Efflorescence. And then, Janine, you gave me some more today. I mean, just: seeds, shrubs, chaperoning, coalescing, murmurations, that first scar cover. And then, I can’t read my handwriting after that.

[laughter]

So, thank you thank you, thank you, Janine and Azita.

[applause]

[music: “Eventide” by Gautam Srikishan]

Tippett: Janine Benyus’s classic work is Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature. She is the co-founder of the non-profit, Biomimicry Institute. She also co-founded Biomimicry 3.8, a consulting and training company.

Azita Ardakani Walton is a philanthropist and social entrepreneur. Her projects have included, among many things, the creative agency Lovesocial, and the experimental investment vehicle, Honeycomb Portfolio. And, in transparency, The On Being Project has received funding support from her philanthropy.

Special thanks this week to the wonderful 1440 Multiversity team, especially Scott Kriens, Inga Stephenson, Frank Ashmore, Luigi Califano, Manuel Lara, Deric Nadeau, and Amy Natividad –– as well as Avery Laurin, with SNA Event Productions.

And our thanks go to the Wayfarer Foundation and the Fetzer Institute, who supported this Gathering.

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Laurén Drommerhausen, Eddie Gonzalez, Lucas Johnson, Zack Rose, Julie Siple, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Gautam Srikishan, Cameron Mussar, Kayla Edwards, Tiffany Champion, Andrea Prevost, and Carla Zanoni.

On Being is an independent nonprofit production of The On Being Project. We are located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. Our closing music was composed by Gautam Srikishan. And the last voice you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

Our funding partners include:

The Hearthland Foundation. Helping to build a more just, equitable and connected America—one creative act at a time.

The Fetzer Institute, supporting a movement of organizations that are applying spiritual solutions to society’s toughest problems. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, dedicated to cultivating the connections between ecology, culture, and spirituality. Supporting initiatives and organizations that uphold sacred relationships with the living Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org.

And, the Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections