Jennifer Bailey and Lennon Flowers

Cultivating Brave Space

Lennon Flowers and Rev. Jennifer Bailey embody a particular wisdom of millennials around grief, loss, and faith. Together they created The People’s Supper, which uses shared meals to build trust and connection among people of different identities and perspectives. Since 2017, they have hosted more than 1,500 meals. In the words they use, the practices they cultivate, and the way they think, Flowers and Bailey issue an invitation not to safe space, but to brave space.

Editor’s note: The original title of this episode was “An Invitation to Brave Space,” taken from the name of a poem credited to Micky ScottBey Jones that is read at the end of this conversation. We have changed the title because it was revealed in June 2021 that Micky ScottBey Jones plagiarized the majority of “An Invitation to Brave Space” from an untitled poem written by Beth Strano. According to The People’s Supper and Faith Matters Network, Micky initially said the poem was “inspired by the words of an unknown author” before later claiming sole authorship. At the time of this note, she is participating in a transformative justice process with Beth Strano.

© All Rights Reserved.

Guests

Jen Bailey is Founder and Executive Director of the Faith Matters Network and serves on the staff of Greater Bethel AME Church in Nashville, Tennessee. Her first book, to be published in October 2021, is called, To My Beloveds: Letters on Faith, Race, Loss and Radical Hope.

Lennon Flowers is co-founder of The People’s Supper and the co-founder and executive director of The Dinner Party. She is also an Ashoka Fellow and an Aspen Ideas Scholar. She has written for CNN, YES!, Forbes, Open Democracy, EdWeek, and Fast Company.

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: Lennon Flowers and the Reverend Jennifer Bailey embody what I experience as a particular wisdom of millennials. They’ve each founded non-traditional organizations that are attending to human needs the world they were born into did not know what to do with. Lennon, whose mother died when she was in college, has helped create a national movement for opening up about grief and loss in the lives of young people over shared meals. Jen is a celebrated innovator at the intersection of, among other things, theology, community organizing, spiritual sustainability, and intergenerational accompaniment. Together, they’ve also made over 1500 “People’s Suppers” happen across the political chasms of the last few years. In the words they use, the practices they cultivate, the way they think — they issue an invitation to something different from “safe space”: brave space.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

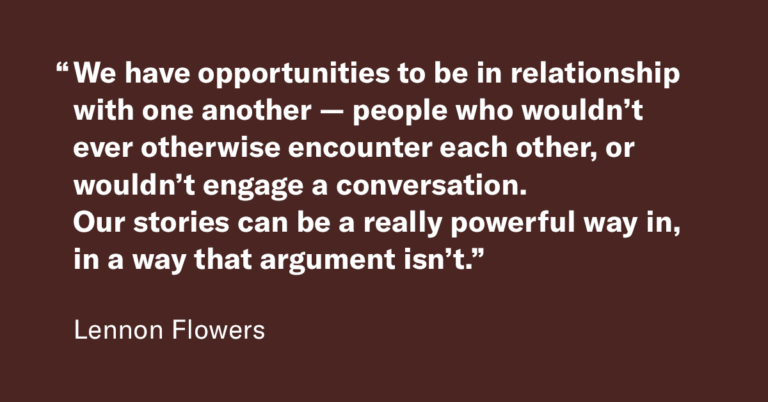

Lennon Flowers: We don’t need to confuse safe spaces with comfortable spaces. And we don’t have to understand everything about each other in order to be present with one another. I think that we have mistaken empathy as walking in someone else’s shoes. Let us be clear, you can’t. But what we can do is witness, and accompany.

Jennifer Bailey: One of the things that is so true about the work that we’ve been up to, but, I think, this moment, is that we expect people to come out, fully formed. And the reality is, if we are gonna do the work of what it means to grow into being fully human, to grow into the promise of America, to grow into — to be in process, then we have to be teachable. We have to be moldable. We have to be willing to engage one another and be wrong sometimes.

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

Rev. Jennifer Bailey is founder and leader of the Faith Matters Network. Lennon Flowers is co-founder of The Dinner Party. And they are co-founders of The People’s Supper initiative. We spoke together in the historic amphitheater of the Chautauqua Institution as part of its 2019 summer season.

Ms. Tippett: Jen, I’d love to start with you about hearing how you would begin to describe the spiritual or religious background of your childhood.

Rev. Bailey: Well, thank you, Krista. As a reverend, you might infer that it’s rooted in the church. And for me, when I think about the spiritual background of my childhood, growing up in the late ’80s, early ’90s, and through the 2000s, it’s very connected to place — and, in particular, the place that is my hometown, Quincy, Illinois, a town of about 40,000 people, right across the river from Hannibal, Missouri, that is, when I was growing up, 90 percent white and 10 percent “all others.” And being a part of that “other,” growing up, was not an easy experience. It wasn’t easy being a little black girl in Quincy, Illinois. I remember really distinctly being five years old on the playground of Adams Elementary School and being told that I must be dirty, because why else would my skin be brown? And for me, the one place that I could find a sense of belonging, the one space in my life where I was told that I was beloved just because of who I was, was at Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church on the corner of 9th and Oak Street.

And it was there where I was — I was taught in the church kitchen by the women of the church — that space that is largely our domain — it was in that space that Sister Weldon told me, when I was 7 years old, that I would be a preacher girl one day.

[laughter]

And those words of affirmation, that affirmation that I was, indeed, beloved in the eyesight of God, that my brownness was something to be honored, that God delighted in me, really happened in those kitchen spaces of the church.

Ms. Tippett: You’ve also written beautifully about learning to raise your voice at your grandmother’s table — somewhere you said, “over pots of greens and black-eyed peas and games of spades” — and that there was a truth-telling you learned there.

Rev. Bailey: So I say I had two grandmas, one of whom had the key to her church, and one her pastor did not …

[laughter]

… and the other one — yeah. [laughs] And you can attach all you want to that. And then there was my grandma Vera, who was not a churchgoer. I knew very much — it, it was spades and bid whist on the South Side of Chicago.

Ms. Tippett: Oh, so that was her table.

Rev. Bailey: That was her table, where I learned about a particular type of truth-telling that happens after one to two Budweisers, right?

[laughter]

But in that truth-telling was sacred space. And it wasn’t the same sacred space that I experienced in the church kitchen; it was a sacred space that allowed for a type of dissemination of knowledge. And I think those two experiences with my grandmothers, in the church kitchen and at my grandmother’s kitchen table, really informed both my theology and what it means to be a black woman in today’s United States.

Ms. Tippett: Lennon, I know less about your story. How would you describe the religious or spiritual background of your childhood?

Lennon Flowers: I think the spiritual background, for me, is an easier one to land on. I grew up in Raleigh, North Carolina. And I grew up between worlds. So one was a very middle-class world from which my mom entered, after an escape from one of endemic poverty in eastern North Carolina. And it was the world of my extended family in tobacco country, and I grew up surrounded and vacillating between spaces and people who lived in very, very different conditions. And I think one of the things that I took away from that and that my mom was really adamant that I do was to never, ever confuse a person’s capacity with their circumstances and to be able to seek out and look for capacity and to recognize — my mom was extremely private in her own religious views, to the point that when she died, I still don’t know definitively what she believed. But one of her favorite phrases was “There but for the grace of God, go I.” And the serenity prayer was taught to me at an extremely early age.

And I think the second piece that she was — the second teaching from that experience was — she didn’t romanticize poverty. And I think the people who tend to are the ones who’ve never known it. But neither did she romanticize wealth. And for her, what was supremely important as a currency that mattered was the use of your voice. She grew up in circumstances that can make you feel very, very small. And so she was really clear for my brother and me that we could be big and that what mattered in this life wasn’t anything attached to the money that we earned or anything like that, but doing something that mattered and mattered to us.

Ms. Tippett: And there’s so much resonance; this is such an unusual entry point to talking about this moment we inhabit, in civic and civilizational terms. There’s so much resonance with that experience and those insights, and how do we live together now, and how do we move forward into new realities. And so The People’s Supper started after the 2016 election, and I know that that was a really cathartic experience for the two of you. And something I appreciate so much about the way you speak about it and, also, have acted on that catharsis, is not to turn it into a partisan battle. It is to address it at this human level of what we know about being human, and honoring that and ennobling that.

Jen, I first met you at a gathering of mostly millennials a couple of months — I think maybe November 2016. And I think you were supposed to give a talk, or maybe a TED-like talk, and you instead delivered a sermon, which was amazing. [laughs] And then I think I invited you to write this piece for the On Being space about what you’d said. And I’m gonna read a little bit of this. “I am a black woman ordained in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. I am the breathing legacy of one of America’s great original sins, the child of people stolen from the West African coasts to labor in the fields of Florida, Georgia, and Arkansas.” This is you, after the election. “I folded into myself: my arms wrapped tightly around my knees and found their rest on my heaving chest. Yet, as I opened my mouth to cry out to God, as I often do in moments of hopelessness, no sound emerged. […] Rocking back and forth on the cool linoleum floor, I finally uttered the only words that I could find, ‘I don’t feel safe. I don’t feel safe.’”

You reminded me, in that moment, that the meaning of the word “apocalypse,” in the biblical Greek, is not a catastrophe to end all catastrophes. The meaning of that word is “an uncovering.” And you also wrote this: “Regardless of where you fall on the ideological spectrum or how you cast your vote, one thing is exceedingly clear” — that that “presidential cycle uncovered and left exposed a rupture at the very heart of our democracy.”

So the two of you, I guess, started talking, just as you started The Dinner Party with another friendship, which I think is also a theme, in terms of how you all, and your generation is approaching social change.

Rev. Bailey: What’s resonating now, hearing those words back, is, “I said that?”

[laughter]

It’s also — part of the context for that moment, for me, in November of 2016, is that I’d lost my mom on Mother’s Day eve, 2016, after a 14-year battle with cancer. And what I felt when I was rocking back and forth on that floor and saying, “I don’t feel safe. I don’t feel safe,” was her presence come over me and say, “We’ve never been safe.” And it was a reminder for me that, as someone who grew up for — in her case, she was part of the first class to integrate her high school in Cairo, Illinois, in 1968 — that safety is an illusion that’s only afforded to a few people. And so the choice, which my friend Micky reminds me of, is, some of us have to be brave.

And when I reflect back on that moment, and when I reflect back the next week, I was driving from Nashville, Tennessee, where I live, to Little Rock, Arkansas, and I drove through my grandmother’s hometown of Hughes, Arkansas — the one that was playing bid whist — I remembered stories. And I remembered the stories of what it was like for my other grandmother to experience a lynching in her hometown when she was 11 years old. And so I think it was out of a space of recognition — and the “uncovering” moment, for me, was just exposing what generations of my family had always known had been at the heart of our democracy, which was this great sin of white supremacy and — and — and the “and” becomes really important to me — that we were the product of those who survived.

And, as I reflect on this moment in American history, and when I reflect on the future children I hope to have, my hope is that it’s by creating small spaces like the ones that we’ve been able to do through The People’s Supper, that perhaps we can begin to imagine and realize what the promise of America could be.

I was with Ruby Sales, a mentor of ours at Faith Matters Network —

Ms. Tippett: The civil rights elder.

Rev. Bailey: Civil rights elder who — if you want to humble yourself, just spend some time with elders. [laughs] And she reminded me of a phrase that old black folks used to say to her when she was going through the Civil Rights Movement, which is that “You’re in process,” the implication being that none of us has quite arrived yet. And I think, in America, we are in process. And we are at a really deep and important moment of uncovering that is ugly, and there is a choice before us. And the question is whether or not we will continue to be in process towards the promise of what America could be or default into the worst of our instincts.

[music: “Romantic Works (feat. Ren Ford)” by Keaton Henson]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today at the Chautauqua Institution with Rev. Jennifer Bailey and Lennon Flowers.

Ms. Tippett: And I think a wisdom that the two of you have from your families and from the work, focusing on grieving, focusing on pain and loss — and this corresponds with what we’re learning in brain science — is that when we humans begin — are reduced to our pain and our loss and our fear, we cannot be our best selves. And I feel like that’s not the only thing that needs to be attended to, but it is something. You’re creating these literally nourishing spaces [laughs] around the table, which doesn’t now surprise any of us, for people to bring their humanity, whoever they voted for, whatever their identity is on the spectrum of all of our divisions.

Tell us what that’s been like, what you’ve experienced.

Rev. Bailey: Hard. [laughs]

Ms. Flowers: Hard.

Rev. Bailey: And I say that, not flippantly, but I think it has been — I will self-identify as someone who identifies as part of the political left, who is embedded and nourished by communities working and striving towards social justice. And one of the first instincts that I think a lot of my peers had post-election was to gear up for the fight. And I think, for many, many reasons, that was the right decision for some of them. And what I remembered, in this time where so many of us were throwing accusations at one another, was a really distinct memory. I was 14 years old. My mom had just gone into the hospital for the first time after her cancer diagnosis, and I was sitting at a kitchen table. It was my birthday. And I heard a knock on the door, and it was Erin Cherington, who is the mother of one my best childhood friends, and she brought me a birthday cake. Now, Miss Cherington is a conservative Catholic woman; I don’t know how she voted last election, but I can guarantee you that in elections before that, we probably did not vote the same way. And for me, that memory of this connection with somebody who was part of a mothering community for me growing up, who had a very different political ideology than I did, was the thing that called me back: called me back from the ease of cynicism, of accusation, and reminded me of the deep humanity that still existed in what I might call my political foe.

And so translating that story, and sharing that with some folks for whom — and this is something Lennon and I have talked about quite a bit as a lesson from The People’s Supper — sometimes it’s unethical to ask certain people to bridge. Some people aren’t ready to bridge yet, particularly those who inhabit particular marginalized identities that are under attack —

Ms. Tippett: People who are literally in danger should not be asked to be bridge people.

Rev. Bailey: Exactly.

Ms. Tippett: But some of us, as you say, can be brave.

Rev. Bailey: And but for those of us who are called to that type of work — which is not everybody — but for those of us who are, I feel a particularly deep responsibility to step into that space and be what I think any good preacher is, which is a translator: to be able to use the words of a faith, in some cases; in others, to begin knitting together a little more of that fabric that I think is so important to what the American project is.

Ms. Tippett: I want to talk about, just in these few minutes, some of the vocabulary and the practices that have emerged through what you’ve done — some of it emerged in The Dinner Party or in Faith Matters and have found their way into People’s Supper, but I feel like they’re so instructive and nourishing, actually, to hear about.

So Lennon, you had this notion in The Dinner Party, that we talk a lot about self-care and that there’s also a need for collective care, that we might live “better, bolder, and more connected lives.” So talk about what that distinction is for you.

Ms. Flowers: I think self-care — I think one of the things that we forget about self-care is that it doesn’t work in isolation, and we live in a time of endemic loneliness, and that part of what tethers us to life on Earth and makes it great are the people we care about and the people who care for us. When you look at — there’s a study recently that millennials and Gen Z are one of the loneliest demographic groups, have higher loneliness scores than people ages 72 and older.

But when you actually look at what is driving that, social media wasn’t what was predictive. People who spent a lot of time online had the same loneliness rates as people who spent less of it. What was actually predictive was the presence of in-real-life conversation and connection, the relationships in your life. But relationships — I think, let’s make no mistake, relationships aren’t a thing that can be compelled, either.

Ms. Tippett: That can be what?

Ms. Flowers: They cannot be compelled. And so, what are the conditions that invite that? And part of that answer is time.

Ms. Tippett: Is time. That’s right. I think what makes all of this possible and bearable for the two of you is very countercultural to the way American society has functioned for a long time, where time is money, and you do things quickly, and you get them resolved, and you move on, and you have an action plan or you take a vote, and you move on. And I see this in your generation, is a long, reality-based sense of how long social change takes. I feel like — Jenn, I’ve heard you — I feel like you are really picking up this language of Martin Luther King, Jr., of the long arc of the moral universe —

Rev. Bailey: One thing — our mantra, a mantra we have at The People’s Supper is always that “Relationships move at the speed of trust, but social change moves at the speed of relationships.” And whew, what a relief. [laughs]

And what I mean by that is —

Ms. Tippett: And didn’t Stephen Covey —

Rev. Bailey: He started that, yeah.

Ms. Tippett: It’s interesting, because Stephen Covey had this language of “the speed of trust,” but it was very much about productivity and getting things done. And you’re picking that up and just shifting it. Say it again.

Rev. Bailey: “Relationships move at the speed of trust; social change moves at the speed of relationships.” There’s been no movement for justice or equity in this country that didn’t start with relationship. Doesn’t happen singularly. And so, as I think about this work of social change that we’re undertaking, the transformative practice of trying to build the America that we want to see, it’s a generational project. And thank God that I believe in a faith tradition that — my time currency is eternity. It’s not — [laughs] not election cycles.

[music: “Derano” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Ms. Tippett: After a short break, more with Rev. Jennifer Bailey and Lennon Flowers. We are thrilled to be hosting the beautiful People’s Suppers resources they’ve created for you to download and use. Go to civilconversationsproject.org. There, you’ll also find this and other conversations, together with On Being’s Better Conversations Starter Guide and Grounding Virtues.

[music: “Derano” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today with millennial wise women, the Rev. Jen Bailey of the Faith Matters Network and Lennon Flowers of The Dinner Party. Together they made over 1,500 “People’s Suppers” happen across the political chasms of the last few years. We spoke together as part of the 2019 summer season of the Chautauqua Institution in its historic outdoor amphitheater.

Ms. Tippett: The reason I think what you’ve been doing, and you too, is actually more relevant than every bit of political punditry is that there’s something about this advanced age we’re in that politics has just now — and the economy — have become this thin veneer over the human drama, over these questions of what it means to be human and how we want to live, over the drama of pain and fear and dreams and hope.

Ms. Flowers: I think we have forgotten that we can be each other’s medicine. The People’s Supper, I think I began that work with profound levels of naïveté in a thousand different ways. But one of them was the presumption — our work began as a hundred-day project, which we thought was, like, eternal time in Twitter time, so yes, we are capable of long games, and also, sometimes, can speak the length of a tweet. And our intention there was to gather 100 dinners over 100 days.

And we did that, and we did a lot more than that, and there was a continuing appetite to keep gathering, but one of the things that we had found in that was, actually, a lot of really problematic motivations.

Ms. Tippett: In yourselves, or just all over the place?

Ms. Flowers: Oh, both/and. OK? And I think what I had failed to appreciate in that was that there’s a lot of work — I had to interrogate my own whiteness. Is it is easy — we draw a lot of attention to this political moment and point fingers at the white supremacist who just shot up a Walmart in El Paso and the collective grief experience that attends that. But I think one of the things that we noticed was — early on, we heard from a lot of white progressives — an old colleague of ours coined a term for “white women who like to hike,” WWWLTH, and hi, I’m a white woman who enjoys hiking.

But what people were looking for was a moment to match the optics of their lives with the values they profess to hold and their voting patterns every four years. So they wanted to sit down with a token person of color, a token immigrant, preferably undocumented. They wanted to have a moment to elevate or bend their eyebrows in kind of a pity face and to show that they were every bit as compassionate as they thought they were. They wanted to sit down with a Trump supporter and prove that they were morally and intellectually superior. They wanted to take a selfie at the end of the night. And they wanted to be done.

And that isn’t the way that social change works.

That is not the conditions of relationships.

[applause]

Rev. Bailey: I think the great question of the 21st century is the question of how we “be” together. And I use that language intentionally, the African-American vernacular English, rather than the — how we be. And for me, it’s about not just how we be, in terms of our personhood, but how we do this American project together, because we’ve never actually been successful at it yet. And so the aspiration to live in a multi-religious, multi-ethnic, multi-racial democracy is an aspiration. And God, what a project to pursue. But if we don’t get it right in these small ways, and building those relationships of trust over time, recognizing the historical and real, modern-day reasons why there are these deep ruptures — I think about — we talk about white supremacy in this country, or white nationalism. It’s not hypothetical, for me. About two months after the Charlottesville incident, an hour south of my house, there was a rally of many of the worst groups that were there. And for me, when I hear people chant stuff like “Blood and soil” and “Jews will not replace us,” I think about my future children, as someone who is an African American, living in the South, married to a practicing Jew — our future kids are the embodiment of everything these people profess to hate. And so it’s real. There are real, lived consequences for people worshipping what I think of as the god of white supremacy.

For me, white supremacy is not an ideology, but a theology, and what is required of it is both the blood sacrifice of black and brown bodies and for white folks to give up a true part of themselves in the process: to forget their histories. So when I think about — Lennon, you were mentioning grieving practices earlier — I actually do think we have some ancestral ways of knowing how to grieve. It’s why black funerals take about five to eight hours. [laughs] It’s why, when I think about my friends who live in Ireland and other places, there are these rituals and practices that we know but we’ve forgotten. And in fact, for many people they’ve been asked to give up, to assimilate into a vision of whiteness that erases the particularity of their story. And what an act of violence that is, as well.

Ms. Tippett: I think, also, just the dinner party, the supper, the shared supper, the hospitality to strangers, whether you voted the same way or not. That’s never what hospitality was about. It’s about inviting people to bring their best selves into the room. Here’s some language about — I think this is language from The People’s Suppers: “While people share their stories and bare their scars, the group has a responsibility to elevate and hear their stories.” You talk about this as being “brave space.” “Brave space works to create a space that is supporting, healing, and nurturing to all involved.”

That image that we get from that language so contradicts what happens in too many of our most highly-publicized and political public spaces now. But it is this ancient technology of gathering around the table and breaking bread together.

Rev. Bailey: This question of bringing people to the table when — folks want to fight right now. I go back to the language of invitation, which is different than demand. And so I think one of the things that we’ve been really intentional about in the methodology of The People’s Supper in particular is that we don’t lead with questions around your political identity or what you think about headline X, Y, or Z. What we begin with is the question of telling your story.

So, our bridging suppers that we’ve used to bridge across lines of political difference start with the question, “Describe a moment, recent or long-since passed, when you felt isolated, alone, or unwelcomed.” And what that does is begin to let people settle into a shared experience, because we’ve all had an experience of that, rather than going up — because once you start talking politics, people’s guards immediately shift, and they go into fight mode and not a mode of invitation.

Ms. Flowers: I think that meals also create a rhythm in a conversation. And I think some of the stupidest things that we say are because we’re trying to fill silence, or we’re trying to cover. And so, instead, the ability — when you’re actually giving thought to what is really true for you, the ability to pick up a fork or a glass, to take pauses that don’t feel awkward. And I think one of the things that we try to instruct everyone in is the difference between embracing silence as a gift versus being silenced. And there are a lot of ways in which we can silence each other, but silence itself is not at all the enemy in conversation.

I think that there’s a familiarity to a meal, because we all gotta eat, and our food does tell the stories of where we come from. But it also — we encourage hosts, particularly for larger events in congregational spaces or civic spaces, to use the moment of dessert as actually a cue that things are gonna start to wind down now. And that way, you don’t actually have to have a phone or a watch and looking down, but a host can know that in about 15 minutes, we’re gonna start to bring the conversation in. And I think that allows us to be really present with one another.

[music: “Homesickness” by Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guébrou]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today at the Chautauqua Institution with Lennon Flowers and Rev. Jennifer Bailey.

Ms. Tippett: I want to talk about the notion of accompaniment, which we’ve been talking about, but it’s an important word for you; I think somewhere you said that this is the most sacred element of your work.

Jen, in that piece that you wrote for us after the election, you quoted Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., saying, “Where do we go from here, chaos or community?” That was his question. And you said, “I choose community. The community I long for will not be found in shallow platitudes promoting reconciliation. It will require the courage of everyday heroes to dig deep and find within themselves the wherewithal to lean into one another and repair the breach of relationships this election has exposed.”

So we’ve been talking about bringing people together, about eating together, but I want you to just talk about all the nuance, for the two of you, that this word — that “accompanying” each other holds for this age we inhabit together.

Rev. Bailey: There’s a quote I love that says, “We are each other’s business.” And for me, I’m very aware of the urgency of now. There is a climate crisis that is afoot. There is a crisis on our borders and the creation of borders between us. And I know that the only way that I know to get through that is to be walking alongside one another in that journey, through the valleys and the mountaintops. And that means not giving up on each other, not casting one another aside, but inviting us into deeper-ness, if that’s a word. I don’t know if that’s a word. But I think about this moments of reckoning that are upon us. And for me, our narratives of reckoning are incomplete without pathways for redemption that hold us to account for some of the awfulness and the messiness, but also allows ways for us to reintegrate people into community, because it’s when we start to cast each other aside, when we don’t do the work of walking alongside and being with one another through the shit, if I can say that — I’m sorry. That’s not very reverend-ly language — but that’s where you start to foster community. And I think one of the great gifts of still being embedded in a church community is that I’m still in intergenerational space with folks.

Before I left Nashville yesterday, I was in my church kitchen — so many connections to church kitchens — [laughs] with Miss Hazel, and she was sharing with me, as we were reflecting on the events in El Paso and in Dayton, and I told her, “My heart is broken. And I’m happy my heart is broken, because I was afraid that I’d become too complacent.” And she began to share with me the experience of growing up in the 1940s and ’50s and ’60s in Nashville, Tennessee — and her resilience — that word becomes important to me — and that resilience of being able to get through when the Klan burned a cross on her front yard because her brothers integrated the local elementary school, that it was with each other that they were able to get through. And so, for me, that’s why accompaniment — and this word is so important — is because it’s only in community that my people have gotten through, and I think it’s the only way that we’re gonna get through.

Ms. Flowers: I think we’ve really outsourced the role of being human to experts and professionals. And really, what does it look like to reclaim our humanity and to recognize that — I think, sometimes, it isn’t — I think about growing up in the “post-racial” ’90s of America and so much of what wasn’t talked about as it related to race and racism and whiteness. And some of that wasn’t always the product of overt racism and denial — or the equivalent of Holocaust denial. It was discomfort. And I think recognizing that safe spaces — and this is back to the language of “brave space” that has been so formative — is that we don’t need to confuse safe spaces with comfortable spaces. And we don’t have to understand everything about each other in order to be present with one another. I think that we have mistaken empathy as walking in someone else’s shoes. Let us be clear, you can’t, because that person lived a lifetime in their shoes. But what we can do is witness and accompany.

Ms. Tippett: I think you’re actually pushing against some of the instincts of your generation, also, in working with the language of “safe space” in that way. And I can imagine that this is kind of controversial. And I think it’s really important, because you’re — this is me walking into this dangerous territory — but clearly, that language of safety and lack of safety has its meaning, but I agree with you that sometimes it’s being confused with being uncomfortable, and then it becomes something that, in a weird way, is dehumanizing for everybody.

Rev. Bailey: In the words of our colleague Micky, there’s a part in the poem that she wrote, “An Invitation to Brave Space,” which has been the one document that has anchored every single People’s Supper, which is: “We have the right to start somewhere and continue to grow. We have the responsibility to examine what we think we know. We will not be perfect.” And I think one of the things that is so true about the work that we’ve been up to, but, I think, this moment, is that we expect people to come out fully formed. And the reality is, if we are gonna do the work of what it means to grow into being fully human, to grow into the promise of America, to be in process, then we have to be teachable. We have to be moldable. We have to be willing to engage one another and be wrong sometimes.

And there has been such a culture — and I think it comes from a good instinct, to want to protect — and I know, in my community, it’s been silence around particular racialized traumas that people have experienced in previous generations, and what my aunties and them didn’t say. And they did that out of a desire to protect me from the harsh realities of what it meant for them to grow up when they grew up and where they grew up in the South, and — and it still is live. And so, I think there is a generational conversation to be had, cross-generations, about the fine line between what it means to protect and what it means to tell the truth and hold one another in truth well, to accompany one another in the telling of truth well.

Ms. Tippett: In reality in all its complexity, the world as it is, and not as we wish it to be.

Rev. Bailey: Exactly. Exactly.

Ms. Tippett: I do want to throw in here that part of accompaniment is insisting on joy and refreshment and resilience, and that one thing accompaniment is about is understanding that on any given day, it might be too much for you or me to ask, to carry — even to be hopeful. And so, on those days, you have somebody else who can carry that for you. And I feel like joy is also strangely countercultural right now.

Rev. Bailey: I don’t want a revolution if I can’t dance, y’all.

[applause]

There’s a reason why I hold scripture in one hand and Beyoncé lyrics in the other…

[laughter]

…that there is joy to be found in the silly moments, in the quiet moments, in the moments that — I agree with you that joy seems countercultural. But what is more revolutionary than declaring that there are things that are worthy of our laughter, that there are things that are worthy of celebrating at a time when everything seems so dark and dim? I live my life in color, not in black and white.

[applause]

And that’s another thing we’ve always known. There’s a reason why the elders of the movement, the Civil Rights Movement, were singing songs. There were reasons why they were cooking together and just being together. And so much of that relationship, that trust, is built over late-night bottles of wine on front porches [laughs] and …

Ms. Tippett: This is also not an either/or; it’s a both/and.

Rev. Bailey: It’s a both/and. We get to live full lives. And when we stop living full lives, we give ourselves over to hopelessness. And I belong to a faith tradition that is all about revolutionary hope and always orients itself towards a notion of resurrection, not resurrection that is born of platitudes, but a deep reckoning with sorrow and death — and that we imagine something different, that we can begin to live into something different.

That’s the fancy term I learned in seminary: the eschatological hope. That is the vision of what might be. And man, if that Jesus guy, for me, didn’t live that example. He was drinking, too, and sharing tables all the time.

[laughter]

Ms. Flowers: I think this is what humans have been doing with each other: sharing joy and sorrow with the people that we love, and recognizing — the first time somebody shows up to a dinner party, it’s the ability — I think we obscure our pain and our suffering with platitudes and empty words and trying to find the rainbow at the end of unfixable realities. But the thing that keeps people coming back over time is, you have to have moments of joy and laughter and vitality. That is the bread upon which our friendships and our lives are built. And it is space in which to be and hold all of it.

Ms. Tippett: I want – to close, I want to ask you all to read the full — this “invitation to Brave Space,” this poem that is so central; you just read the first few lines. And we had a printer crisis at the place I’m staying, just before I came over, so I was unable to print this out. But luckily I had this beautiful invention, the iPhone, so why don’t I give it to you, Lennon, and you just read the first half, and then pass it to your friend.

Ms. Flowers: “An Invitation to Brave Space,” by Micky ScottBey Jones:

“Together we will create brave space

Because there is no such thing as a ‘safe space’

We exist in the real world

We all carry scars and we have all caused wounds.

In this space

We seek to turn down the volume of the outside world,

We amplify voices that fight to be heard elsewhere,

We call each other to more truth and love”

Rev. Bailey: “We have the right to start somewhere and continue to grow.

We have the responsibility to examine what we think we know.

We will not be perfect.

This space will not be perfect.

It will not always be what we wish it to be

But

It will be our brave space together,

and

We will work on it side by side”

Ms. Tippett: Thank you, Rev. Jen Bailey and Lennon Flowers.

Rev. Bailey: Thank you.

[applause]

Ms. Tippett: It’s great to see the future looking like this, isn’t it?

[applause]

[music: “Composure” by B. Fleischmann]

Ms. Tippett: Micky ScottBey Jones, who wrote the “Invitation to Brave Space” poem, is the director of Healing Justice at the Faith Matters Network, the organization Rev. Jen Bailey founded and leads. Faith Matters joined with Hollaback! and The Dinner Party to create The People’s Suppers. And Lennon Flowers is co-founder and Executive Director of The Dinner Party.

You can find out more about the wonderful work of The Dinner Party at thedinnerparty.org and about Faith Matters Network at faithmattersnetwork.org.

And again — we’re making available the beautiful People’s Suppers resources they created at civilconversationsproject.org. There you can also listen to this again and find On Being’s Better Conversations Starter Guide and Grounding Virtues. Again, that’s civilconversationsproject.org.

Staff: The On Being Project is Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Maia Tarrell, Marie Sambilay, Erinn Farrell, Laurén Dørdal, Tony Liu, Erin Colasacco, Kristin Lin, Profit Idowu, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Damon Lee, Suzette Burley, Katie Gordon, Zack Rose, Serri Graslie, Nicole Finn, and Colleen Scheck.

Ms. Tippett: Special thanks this week to Michael Hill, Matt Ewalt, Emily Carpenter, Rachel Borzilleri, and the Chautauqua Institution.

[music: “First Train Home (Instrumental Version)” by Imogen Heap]

The On Being Project is located on Dakota Land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by PRX. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, working to create a future where universal spiritual values form the foundation of how we care for our common home.

Humanity United, advancing human dignity at home and around the world. Find out more at humanityunited.org, part of the Omidyar Group.

The George Family Foundation, in support of the Civil Conversations Project.

The Osprey Foundation — a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.