Jo Anne Horstmann

L'Arche: A Community of Brokenness and Beauty

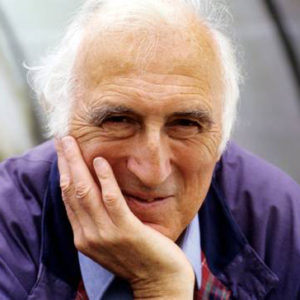

Editor’s note: In February 2020, L’Arche International released the results of an independent investigation that it commissioned into Jean Vanier, who died in 2019. The investigation determined that the L’Arche founder, Catholic philosopher and humanitarian engaged in manipulative sexual relationships with at least six women from 1970-2005. None of the women had disabilities. The report also concluded that Vanier was complicit in covering up similar sexual abuse by his mentor, the late Father Thomas Philippe. In this response, Krista reflects on the moral questions and meaning raised by these discoveries.

Forty years ago in France, philosopher Jean Vanier founded an international movement, L’Arche. The L’Arche community in Clinton, Iowa is part of this movement — people of faith living and worshipping alongside developmentally handicapped adults. There are now over 120 L’Arche communities in 18 countries. The community in Clinton is one of the oldest and most rural of the 14 American communities. In this “radio pilgrimage,” we take listeners into a radically different faith community that confronts our assumptions about service and diversity, and the worth of individuals.

Image by Papaioannou Kostas/Unsplash.

Guests

Jo Anne Horstmann serves as regional coordinator of the L'Arche Federation for the central U.S.

Jean Vanier was a philosopher and the founder of L'Arche. He was also the recipient of the 2015 Templeton Prize. His books include Befriending the Stranger, An Ark for the Poor, and A Cry is Heard: My Path to Peace.

Transcript

August 2, 2007

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett. Today, a radio pilgrimage to L’Arche—a community formed around people with mental disabilities, and others who share life with them. At the heart of the L’Arche movement is a countercultural idea of difference as normal and imperfection as a source of strength.

MR. ERIC PLAUT: What I’ve experienced in L’Arche has been many times that beauty of things that go wrong even, or that don’t go according to the way we would like them to or according to our plan, but they’re still wonderful. And that’s the charism of L’Arche.

MS. TIPPETT: This is Speaking of Faith. Stay with us for “L’Arche: A Community of Brokenness and Beauty.”

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett. The L’Arche movement is named in the French tongue of its birthplace. It means “the ark,” an old image of all the parts of creation journeying together. In this movement that spans 34 countries, community is formed around people with mental disabilities. Today we’ll revisit our radio pilgrimage into the world of L’Arche—its rhythms of life, its openness to pain and failing, and its habits of love and forgiveness.

From American Public Media, this is Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas.

Today, “L’Arche: A Community of Brokenness and Beauty.”

[Voices laughing]

WOMAN 1: Yeah. …you going to write—you going to write yours down in your book? How’d you do at work? Whoa, 650 bags!

WOMAN 2: Yes!

MS. TIPPETT: Increasingly in our culture, the word “community” is an offshoot of identity politics. It is used to group people who think or act alike. But at the heart of L’Arche is a countercultural idea of difference as normal and imperfection as a source of strength.

MR. JEAN VANIER: One of the realities we’re all called to go through, in those words of Mother Teresa, “to move from repulsion to compassion, and compassion to wonderment.”

MS. TIPPETT: Jean Vanier founded L’Arche in 1964. He had been a British naval officer and then a professor of philosophy in Canada. At Christmastime in 1963, he visited a friend, a Dominican monk working as a chaplain in a small French institution for men with mental handicaps. The world of the handicapped, he says, was new to him, and yet he found himself deeply moved by the friendship and the quality of spiritual openness in these men who were shut away from society.

Jean Vanier began to visit other institutions. At a vast asylum south of Paris, he encountered a concrete prison in which, all day, 80 adult men did nothing but walk around in circles and take a two-hour compulsory nap. “There I was struck by the screams and the atmosphere of sadness,” he would later write, “but also by a mysterious presence of God.”

Jean Vanier bought a small house nearby and invited two men from that asylum to come share life with him. Philippe and Raphael were the founding members of a movement which now has 133 communities around the world, including men and women from many backgrounds, religions, and cultures. Here’s Jean Vanier speaking at St. John’s University in Collegeville, Minnesota, about an experience he had at the original L’Arche community in France.

MR. VANIER: I don’t know whether around here you have some normal people, but I find them a very strange group. I don’t know—I remember—well, one of the characteristics of normal people is that they have problems. They have family problems, they have financial problems, they have professional problems, problems with politics, problems with church, problems all over the place. And I remember one very normal guy came to see me and he was telling me about all his problems. And there was a knock on the door, and entered Jean Claude. Jean Claude has Down Syndrome and, relaxed and laughing, and he just shook—I didn’t even say, “Come in.” He came in, and he shook my hand and laughed and he shook the hand of Mr. Normal and laughed and he walked out laughing. And Mr. Normal turned to me and he said, “Isn’t it sad, children like that.”

[Audience laughs]

He couldn’t see that Jean Claude was a happy guy. It’s a blindness, and it’s an inner blindness which is the most difficult to heal.

MS. TIPPETT: L’Arche founder Jean Vanier.

Most of the 16 L’Arche communities in the United States are in major cities. The community in Clinton, Iowa, was founded in 1974, one of the first, and still the most rural. It took the name The Arch, seeing itself as a bridge between two worlds. With a population of 29,000, Clinton sits along a gorgeous stretch of the upper Mississippi. Its solid red brick buildings and graceful houses tell of an affluent past, as do the busy rail lines, whose whistles sound in The Arch homes many times daily.

[Train whistle]

From a genesis of two people in 1974, The Arch in Clinton has grown to three houses and several apartments. Today, 19 mentally retarded residents and nine non-disabled assistants live within walking distance of each other in a pleasant, leafy neighborhood close to the river.

Jo Anne Horstmann was director of the Clinton Arch for 12 years. She’s now regional coordinator for the L’Arche federation in the central U.S., which includes communities in five states.

MS. JO ANNE HORSTMANN: In L’Arche we talk about the rhythm of our day, to have a balance between rest and work and prayer, solitude and community. It’s like a symphony, you know? Everybody knows their part and they play it well and they make beautiful music together.

MS. TIPPETT: At every L’Arche home the mentally disabled residents are the core members, and the non-disabled are their assistants. I asked Jo Anne Horstmann a simple question, “Who lives here?” She gave me long and vivid descriptions of each core member. Here are just a few.

MS. HORSTMANN: They all have their distinctions that make them unique in all the world, you know? Mary Pat moved in a year ago, and she’s our newest core member. And Mary Pat lived with her mom all of her life. Mary Pat’s 50 years old. And my understanding is that Mary Pat, when she was, like, a teenager, developed rheumatic fever. And she went out before that time, but after the rheumatic fever, her mom, out of love, kept her at home. And it was because that’s what her mom knew to do. That was the best thing that her mom could do for her.

So she moved in, and has just had this new world opened up to her. And Mary Pat talks, and she does really well at work. She goes to church, she goes shopping. She’s in California today. She went on a plane. You know, she’s in California right now on a retreat with Jean Vanier. And that’s what L’Arche is all about, to become home and family for people like Mary Pat.

Then there’s Bob, and he lived in an institution from the time he was 10, so about 40 years of his life. Because Bob really doesn’t have a family, everybody is his brother and sister. Like, he loves sports, and he’ll be watching a baseball team and he’ll say “That’s my brother, that is,” you know? Or “She’s my sister.” And so everybody kind of becomes Bob’s brother and sister. And he kind of, you know, the blood thing doesn’t matter to him, it’s more of a spirit thing and a kindred spirit that he feels with people.

Janice has lived at The Arch for 20 years. And, you know, Janice is another person who just makes everybody feel welcome. She loves to cook. She likes to check out all the cookbooks at the library. Yeah. She always has a great big bear hug for people, gives them little adjustments.

Victor. Victor came in 1981. Like, with Victor, it’s getting harder and harder to understand him. But what Victor teaches me is that presence is the most important gift that you can give someone. And he also teaches me the importance of touch. Because with Victor, you know, we can be sitting side-by-side, and he’ll be talking to me and I’m not understanding a word that he says, but when he holds my hand I know what he’s talking about, you know? And Victor’s a very gentle person, too, you know? Just, we talk about the gifts of the Holy Spirit and one being gentleness. You know, all of our people seem to have that gift of the Holy Spirit, is that gentleness.

WOMAN 3: Oh, yeah. We’ll cut the tags off of it. That’d be a good idea. Mm-hmm. We don’t want you to look like a Minnie Pearl.

MS. HORSTMANN: There were two people who came shortly after I did in 1989, and Dan is one of those two people. And Dan will tell you—if you met him last night and if you were to have driven your car over there, then today he could tell you—he would tell everybody what kind of car you drove because he’s really big on cars and he can remember—like, if you would come back 20 years from now he’ll remember you and he’ll remember the car that you drove. Dan’s dream is to drive a car some day. He would like to take the driver’s test, and that’s kind of his dream. And what he likes to do in his spare time is go around to car lots. He likes to look at cars. And he has a Matchbox car collection and he spends a lot of time with it.

MR. DAN JENSEN: These are my cars and trucks and vans and Jeeps. Corvette, Porsche, Corvette, Firebird, Porsche, Mercedes. This one car I see coming on the road is a Dodge Viper, Dodge Van, a Ram Charger and a Dodge Ram pickup truck, too, Dodge Ram 1500 pickup truck. I see every single one of them coming.

MS. HORSTMANN: There’s John. And John lived with his mom, but John, you know, always talked about wanting to live at The Arch, and so one day his mom decided, ‘You know, I think it’s time.’ She was getting older, and she wanted to see John in a home before something happened to her. And so I was outside of Arch 3 when the assistant had come with John and his belongings. And I heard Johnny yelling out the car window, “The Arch, my new home! The Arch, my new home!” Like, I know people down the block could have heard him because he was just so excited about The Arch being his new home.

MS. CHRIS BRUIN: : Oh, my name is Chris Bruin, and this is my friend, John.

MR. JOHN OLSON: Yeah.

MS. BRUIN: And we share a home with six people in our community, don’t we?

MR. OLSON: My honey.

MS. BRUIN: OK. Oh, what do you like to do when you come home at night after work?

MR. OLSON: I like Elvis.

MS. BRUIN: You like Elvis, don’t you? And what do you like to play with Elvis?

MR. OLSON: I play “Love Me Tender.”

MS. BRUIN: “Love Me Tender.” But you also like to play your guitar, don’t you?

MR. OLSON: Yeah.

MS. BRUIN: And sometimes I play the drums with you, don’t I?

MR. OLSON: I love it.

MS. BRUIN: Oh, yeah. Oh, you saw a play about Elvis, didn’t you?

MR. OLSON: Yeah, I like him.

MS. BRUIN: Elvis impersonators. And then we also went to Rock Island and saw a fellow who was a very good Elvis impersonator, huh?

MR. OLSON: Ooh, I loved that.

MS. BRUIN: Yeah, he was really good. He did all his own singing, and…

MR. OLSON: Hey, I helped him, too.

MS. BRUIN: Yeah, you got up there with him and you had your Elvis outfit on, didn’t you?

MR. OLSON: Yeah.

[John singing along to Elvis song]

MR. OLSON: I love it.

MS. BRUIN: Mm-hmm.

MR. OLSON: I love you.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, a radio pilgrimage to “L’Arche: A Community of Brokenness and Beauty.”

Jo Anne Horstmann began her career as a physical education teacher, and she discovered that she loved working with disabled children. She especially enjoyed their delight in accomplishments which for the rest of us would be routine: skipping ropes, catching a ball. Later, she worked part time in a group home for handicapped children and adolescents. She came to The Arch in Clinton in 1989. I asked Jo Anne Horstmann what distinguishes The Arch from any very good group home.

MS. HORSTMANN: Our assistants make their home with people who are handicapped. It’s not an eight-hour type of job where you come in in the morning and leave in the afternoon, or come in in the evening and leave in the early morning. And also, like, when people come to, quote, “work” at The Arch, it’s more seen as a lifestyle than a job. Really, our life is made up of just very simple things. I mean, our daily life is about cooking and cleaning. And, you know, it’s not what the world would see as very high and lofty, but it’s about the amount of love that we put in what we do that makes it a profound experience.

WOMAN: Who made the coleslaw?

MAN: I know. Eric Plaut.

WOMAN: Marion. It looks great.

MAN: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: I don’t think most people use the words “mentally retarded” anymore. How do you think about that whole subject of language and how you would describe or define the condition of the core members?

MS. HORSTMANN: Oh, it’s certainly a difficult issue today. I think that, you know, we try to change words to stay away from the word “retarded” because of how the word has been used in our elementary days, you know? I always say that, you know, in music we use the word retarded to slow down. It means “to slow down.” Nothing wrong. We don’t take it out of our music sheets. And in L’Arche, we use “core members” because we say that our folks are the center of what we live. You know, life revolves around them. They are the core members of the community.

MS. TIPPETT: I could imagine that there are good programs, but where they don’t, maybe, imagine that mentally handicapped people are capable of the depth of spiritual life that is evident here.

MS. HORSTMANN: I think that’s true, and I think it’s probably because the way we live draws it out of them and we recognize it, you know, and we call it to attention. We don’t try to avoid it or put it aside, you know? It’s actually a point of the way we live at The Arch and in L’Arche. Our core members teach us to have that complete faith and trust in God and not complicate it, as we can do.

WOMAN: Lord, help us. All people go to heaven like Jesus said, brothers and sisters, cousins, the friends. Lord, help us Arch [unintelligible] nurse and doctor and people are healthy. Lord, help us sit down at the table morning, noon, and night, singing in joy and love. Lord, help us Arch people go to bed, go to bed, prayer, wake up at sunshine. Lord, hear our prayer.

OTHERS: Lord, hear our prayer.

[Singing]

MS. TIPPETT: Here again is Jean Vanier, founder of the L’Arche movement.

MR. VANIER: Just recently in Central America I was visiting an institution where there were 200 people with disabilities. And to tell you frankly, I was almost physically sick. I think I’ve become much more vulnerable in front of places where people are not respected as human beings, where they’re crushed, where there’s no more dialogue.

We all have to reflect on how we’re in front of pain. We’re all running away from it, we can’t stand it, we don’t know what to do with it. We don’t know what to do with the beggar crying out. We find all sorts of reasons for not to look at him. And the whole question is how to stand before pain.

MS. HORSTMANN: What we say that we want to be, and what I think that we are, is we want to be a sign of hope. In the charter of L’Arche we say that, you know, we can’t serve every person with a mental handicap. We’re not out to be a solution for anything, but more of a sign. You know, our visitors are really important, our pilgrims are very important to us because we live this every day, and we can tend to think there’s nothing extraordinary about what we do.

When our pilgrims come in—I like that term—you know, they tell us that we’re living something that’s very unique and very different. And so a lot of times at the end of the week, they’re telling about this wonderful experience that they’ve had and we’re sitting around thinking ‘Wow. Where were we?’ You know, to know that what we’re living and how we’re living, it has a profound effect on hundreds of people. You know, and that’s where the sign of hope comes in.

MS. TIPPETT: Jo Anne Horstmann coordinates the L’Arche communities in the central United States. This is Speaking of Faith. After a short break, a day in the life of the L’Arche community in Clinton, Iowa.

If you would like to learn more about L’Arche and see photos of our visit to the Iowa Arch community, go to our Web site onbeing.org. Also, we’re making it easier for you to listen to Speaking of Faith when it best suits your life. Subscribe to our podcast to get free downloadable MP3s of each program or sign up for our e-mail newsletter with links to our audio and my reflection on each week’s program. Discover more at onbeing.org.

I’m Krista Tippett, stay with us. Speaking of Faith comes to you from American Public Media.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: Welcome back to Speaking of Faith , public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “A Community of Brokenness and Beauty,” we’re revisiting our radio pilgrimage to the L’Arche community in Clinton, Iowa, which is known as The Arch.

The first L’Arche home was founded in France in 1964 by Jean Vanier, a naval officer-turned-philosopher who discovered spiritual friendship in people with mental handicaps. There are now over 133 L’Arche communities in 34 countries. Mentally handicapped adults, known as core members, share a life here with non-handicapped adults called their assistants.

MAN: What are you going to do tomorrow?

WOMAN: What am I going to do tomorrow?

MAN: Yeah.

WOMAN: Well, I might mow the yard if it’s not raining.

MAN: Oh.

WOMAN: What are you going to do?

MAN: Take my books back tomorrow.

WOMAN: Are you going to take your books back to the library?

MAN: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: Gradually I realized that I’m learning less here about disabilities than what people with disabilities seem to teach others of what it means to be human. Again, Jean Vanier, the founder of L’Arche.

MR. VANIER: I remember when a man who had gone through a very deep experience in one of our homes had been kept awake all night by one of the people who had screamed all night. He came to see me the next morning and he said, ‘You know, I wept all morning. I was in the chapel. I thought I could have killed him.’ And we talked about it, and I said to him, ‘You know, I think this is probably one of the most important days of your life. You came to L’Arche thinking you could do good to the poor, and you have. You’ve done a lot of good. But today you are discovering that you are poor.’ We all need help, and it’s only as we discover that ‘I have a handicap,’ that ‘I am broken,’ that ‘we’re all broken,’ and then we can begin to work at it.

MS. CAROLYN LUEBE: My name is Carolyn Luebe. A typical day—I don’t know if there is a typical day but I get up with the men in this house—Victor and George, dink, Dan, and Mike. We get up around 5:30 in the morning on Monday through Friday. Victor puts away the dishes in the morning, Dan takes out the trash, and dink will help. He’ll set the table and he’ll help on the days that the garbage truck comes around. He’ll get the trash out to the curb and the recycling buckets. Mike, he helps. He likes to mop the floors. So everybody has things that they like to do. And George, George likes to fold house laundry. So it’s really—we share life together and we really work well together. We enjoy all of that. We enjoy our time together.

MS. TIPPETT: The rhythm of life here also includes a full workday for all the community’s core members. Each weekday they board a city bus for Skyline Industries in Clinton, a sheltered workshop which subcontracts with various industries for special projects and tasks.

MS. ELIZABETH PELTIER: I’m Elizabeth Peltier and I work here in the workshop.

MS. TIPPETT: Can you describe just what kinds of jobs people will be doing?

MS. PELTIER: Oh, there’s material-handling, where they are the ones who supply the other clients with the materials that they need. Then there are other ones that are just strictly packers or heat-sealers. We have a few of them on different machinery around here, too, teaching them how to run nailers and stuff like that.

MS. TIPPETT: Do people change jobs quite often, or…

MS. PELTIER: Oh, yes. Well, I run one of the more diverse lines. We do just about anything that comes our way. So, you know, we try to adjust the job according to what they like or what they need to learn.

MS. TIPPETT: Do you enjoy this work? Is this…

MS. PELTIER: Oh, yeah. I think I’ve found my life’s work. I’m, like, their advocate, you know? I’m their friend, their supervisor, their confidante, you know. It’s really rewarding, too, you know, because, I don’t know, we’ve bonded, we’ve become friends. It’s a nice work environment.

MS. TIPPETT: As we waited for the city bus at the end of the workday, there were dramatic farewells as every supervisor, manager, and truck driver drove out of the premises.

The core members were joking and laughing and waving. And likewise, the people in the cars were leaning out the windows, laughing back, blowing kisses. I suspect that this passionate scene is repeated every day as a matter of routine. Even my colleague, Scott, an engineer who had arrived on the scene to record sound, was quickly welcomed and engaged.

MR. GEORGE HEITT: Hi.

SCOTT: Hi.

MR. HEITT: What your—your name?

SCOTT: I’m Scott.

MR. HEITT: Hi, Scott.

SCOTT: What’s your name?

MR. HEITT: George.

WOMAN: George, hi.

SCOTT: George, hi.

WOMAN: He is my honey.

SCOTT: He is?

WOMAN: Yes.

BILL: My name’s Bill.

SCOTT: Hi, Bill.

BILL: Hi. How are you?

SCOTT: Good.

MS. TIPPETT: When the bus arrived, the driver knew the names of every person who stepped aboard, and he addressed them like friends.

BUS DRIVER: Hi, Kenny.

MR. KENNY JOHNSON: Hi.

BUS DRIVER: Hi, Bonnie. Hi, Mary.

MS. TIPPETT: The seven full-time assistants who make their home at The Arch in Clinton range in age from 35 to 59. At the time of our visit, there was one person who’s been there for a year, and two going on 10 years. They take evident joy in this community and also speak openly of the complex dynamics which life at L’Arche inspires in them.

MS. LEUBE: You go through this honeymoon period where you think that, ‘Gee, this is just really wonderful, what we’re living.’ And then you realize that there are times that are not so wonderful. I think in getting to know the men that I live with and the other core members in this community and the other assistants, I see myself reflected back in them. I see good things about myself; I see those things that I don’t like about myself. I think that’s the thing that I see a lot here is just the vulnerability of people and the struggle that they have in just wanting to belong and to have a purpose and to have a place in this world, to be accepted.

MS. CHRIS BRUIN: : Oh, my name is Chris Bruin. And, actually, I started in 1985 just coming to do relief work, coming on weekends so people could have days away. And then I moved in in 1986. So I’ve been here since November of ’86.

I think maybe that’s something that has changed over the years, and I think just lately with me, thinking that, you know, being success was the things you had and what you acquired. But now it’s not so much that. It’s more, for me, it’s just maybe how I am with others. I think it’s how I start to see my success more now and being comfortable with, you know, without having a lot. And all, that’s where I see my success now. I guess.

MS. HORSTMANN: You kind of lose your own identity in some ways. You know, it’s not like a religious community if you would join a convent or something and, you know, you’d give up the idea of getting married, or you give up all your personal belongings. L’Arche is not like that. Maybe, you know, what you lose is your sense of being able to hide yourself.

MR. ERIC PLAUT: It’s really a struggle for me. It’s more of a struggle than I would have been able to acknowledge when I came here, for sure.

MS. TIPPETT: Eric Plaut has been at The Arch for 10 years. He became interested in working with the handicapped as he left college in Wisconsin. Seeking adventure, he was intrigued when he heard of a new L’Arche community forming in Labrador, Nova Scotia. To prepare, he was asked to do an internship in Clinton. In the end, the Labrador community didn’t get off the ground, and to his own surprise, he began a new life not far from his Wisconsin home, in Iowa. Eric Plaut speaks frankly of the complexities of life at L’Arche as an assistant. He told me about one experience he had at a university conference several years ago to which the whole community was invited.

MR. PLAUT: Probably something like this has happened to most assistants, but when we got there a woman that was receiving us clearly mistook me for a core member and was treating me in that kind of, you know, patronizing way, or like—and then someone had to point out to her, ‘No, he’s an assistant.’ And I think she got embarrassed and kind of ran away. But my reaction to that was that I was really offended. And when I reflect on that now, that is showing me that really I probably still have a long ways to go.

Core members—I don’t think of them as saints, certainly, because there is that tendency to do that, you know, to really look at all of this stuff in a kind of a saccharine way. But sometimes, yes, the things that they do that I consider prophetic, you know, rather than saintly, but prophetic, and sometimes those are very positive models.

You know, I told a story of Roberta and Mary Pat when they were at the Olympics, and how they did their race holding hands, you know, the whole time. And I thought, you know, that, to me, is an example of being able to celebrate sports in a way that the culture could learn from that, you know?

But sometimes the prophetic example is not so positive. So, for instance, one of the core members that’s struggling, you know, with a relationship with someone who’s romantically interested in him but he doesn’t return that feeling, but he’s afraid to tell her that. When I see things like that going on, what’s going on with the core members is they don’t mask those things, you know, as well as many people would be able to do. So that becomes a mirror for me. And those kind of revelations are painful, you know, at times.

And so it’s not all good, maybe. But just the intention is good, and the whole idea of it is really important and valuable in recognizing the giftedness of our people, and also the importance of accepting and being reconciled to weakness and what that means. What I’ve seen, or what I’ve experienced in L’Arche has been many times the beauty of things that go wrong even, or that don’t go according to the way we would like them to or according to our plan, but they’re still wonderful. And that’s the charism of L’Arche.

MS. TIPPETT: While in Clinton visiting The Arch, I rediscover the writings of the celebrated author Henri Nouwen. Nouwen was, perhaps, the most famous L’Arche resident, and his books have drawn many pilgrims to short stays at these homes across the world. At the age of 64 in 1986, after teaching at Notre Dame, Yale, and Harvard and writing a number of best-selling books, Henri Nouwen found himself burnt out. He went to spend what would become the last decade of his life at the L’Arche community in Toronto, which is called Daybreak. One of the books he wrote from Daybreak was about what he learned from a single member of that community, a severely handicapped 25-year-old man named Adam who could not speak, dress himself, walk, or eat without help. Here is an excerpt from that account.

READER: “Recently, I moved from Harvard to a place near Toronto called Daybreak. That is, from an institution for the best and brightest to a community where mentally handicapped people and their assistants try to live together in the spirit of the Beatitudes. In my house, 10 of us form a family. Gradually, I’m forgetting who is handicapped and who is not. We are simply John, Bill, Trevor, Raymond, Rose, Steve, Jane, Naomi, Henri, and Adam.

“I want to tell you Adam’s story. After a month of working with Adam, something started to happen to me that had never happened before. This severely handicapped young man, whom outsiders sometimes describe with very hurtful words, started to become my dearest companion. As I carried him into his bath and made waves to let the water run fast around him and told him all sorts of stories, I knew that two friends were communicating far beyond the realm of thought.

“Before this, I had come to believe that what makes us human is our mind. But Adam keeps showing me that what makes us human is our heart, the center of our being where God has hidden trust, hope, and love. Whoever sees in Adam merely a burden to society misses the sacred mystery that Adam is fully capable of receiving and giving love. He is fully human—not half human, not nearly human, but fully, completely human because he is all heart. The longer I stay with Adam, the more clearly I see him as a gentle teacher, teaching me what no book or professor ever could.

“Once, when Adam’s parents came for a visit I asked, ‘Tell me, during all the years you had Adam in your house, what did he give you?’ His father smiled and said without hesitation, ‘He brought us peace.’ I know he is right. After months of being with Adam, I am discovering within myself an inner quiet that I did not know before. Adam is one of the most broken persons among us, but without doubt our strongest bond. Because of Adam there is always someone home. Because of Adam there is a quiet rhythm in the house. Because of Adam there are moments of silence. Because of Adam there are always words of affection and tenderness. Because of Adam there is patience and endurance. Because of Adam there are smiles and tears visible to all. Because of Adam there is always time and space for forgiveness and healing. Yes, because of Adam there is peace among us.”

MS. TIPPETT: A reading from Henri Nouwen’s book Adam: God’s Beloved. I’m Krista Tippett and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, with a radio pilgrimage to “L’Arche: A Community of Brokenness and Beauty.”

I find The Arch in Clinton to be much as Henri Nouwen described in his writings about L’Arche, a place of astonishing serenity and an almost raucous joy.

WOMAN 1: Oh, yeah!

WOMAN 2: We’ll have a slumber party!

WOMAN 1: Yeah!

WOMAN 2: All right!

WOMAN 1: Yeah!

MS. TIPPETT: In my days here, I couldn’t help but draw connections between the lessons of this place and some of the larger issues in our world, including medical technology. More and more we are able to ensure that babies will not be born with mental retardation. L’Arche didn’t leave me with easy answers, but it placed the questions in a new light. Before I left Clinton, I sat down with Jo Anne Horstmann one last time.

MS. HORSTMANN: It’s hard for me, you know, because I’ve chosen to live and be with people who are handicapped. Parents didn’t choose it, it chose them. And I can sit here easily and talk about the gift of people with a handicap, you know, but I haven’t experienced giving birth and living all the challenges of getting people to the point where we welcome people at the age of 18, you know, all the challenges that go into raising a child with a disability.

MS. TIPPETT: I mean, do you ever ask yourself the question that would be the question most people would ask on the surface: ‘How, if there’s a God, why are children born like this with these terrible problems?’

MS. HORSTMANN: You know, this woman that I talked to a couple of days ago said, ‘You know, I always thought when I get to heaven my first question’s going to be is, “Why did you give me a handicapped child,” you know?’ And there was so much anger in her voice. You know, you could hear it. She wants to know why did God give her this handicapped child? And because of L’Arche I think she’s, you know, she’s really able to see that her daughter, rather than being a burden, has become a gift. But it’s been a painful journey to get to that point.

MS. TIPPETT: When I first arrived the other night, you talked about the core residents’ gift of gentleness, and I was aware of that right away. And it almost made me feel afraid at first. I had this question in my mind whether the world can bear such gentleness, or whether this gentleness can survive in this world we live in. And then, as I’m here for a couple of days and I hear your stories, it feels almost like the gentleness that is sort of hidden, you know, comes out of hiding here in the midst of you.

MS. HORSTMANN: Core members just call us to that, you know, to be gentle with them because they are first gentle to us, you know? And it’s what Jean Vanier saw, you know, 35 years ago when he went into institutions, you know, that here’s a great gift that our society could benefit from, and these folks are being held away from the society. So now they’re in the society and you see how the bus drivers react, and how we react, and how you react, you know? That you have a new sense of what gentleness is all about because of your experience being with people who are handicapped.

MS. TIPPETT: Talk to me about what it means to you, and how you think about the fact that although you are this rather small community in this small town in Iowa, you’re also a part of a much larger movement that is in many countries.

MS. HORSTMANN: It really helps us to know that there’s other people living similar lives. I mean, I just don’t think we could do this if we were just The Arch. It’s a challenging lifestyle, it’s a lifestyle that’s—it’s just founded and you live and breathe commitment. And we’re on this journey together with lots of other people to help us on the way.

[The Arch core members singing a hymn]

MS. TIPPETT: Here’s something else that I want to name. When you speak, you talk a lot about Jesus, and Jean Vanier does, too. So, on the one hand there is this boldness about Jesus, and at the same time L’Arche itself has become more ecumenical, and in some places—I know the communities in India are interfaith. That you have Muslim and Hindu and Christian residents and assistants.

MS. HORSTMANN: Right. I mean, it’s true that when you hear Jean Vanier talk it’s all about Jesus and who Jesus is and how Jesus is revealed to us and how we reveal Jesus to other people. And yet, this international organization that he started is now interfaith. So, you know, it just sometimes goes beyond even our own beliefs into the unifying thing that we all have that need for, again is to love and to be accepted and to be cared for and to be forgiven. And, you know, Jesus in the Gospels was always with the poor. And, you know, Jean Vanier himself, to me, incarnates Jesus more and better than anyone I’ve ever experienced besides, of course, dink and Gary and Birdie.

[Woman and group singing]

MS. TIPPETT: Jo Ann Horstmann is regional coordinator for the L’Arche Federation in the central United States. Here again, L’Arche founder, Jean Vanier.

MR. VANIER: In L’Arche we live this sort of double mystery. There’s the whole presence of Mary in Bethlehem and Nazareth, and Mary’s standing at the foot of the cross. I mean, that has a lot of meaning for us, to stand and to be present and just to say, ‘I’m with you. I’m with you.’

In my own foyer there’s a man called Patrick who, technically speaking, he has a psychosis. And there’s a lot of pain and a lot of anguish and, in particular, at some moments. But when I reflect about Patrick, he has everything he needs. He has good medication, good doctors. He has work, he works in the workshop. He has food, he has home. But what does he need over and above that? He needs a friend. What is essential is somebody who believes in him, who trusts him, who sees in him a presence of God.

MS. TIPPETT: L’Arche Founder Jean Vanier.

When I set out for Clinton, I was fascinated by how L’Arche communities attempt to live a great religious paradox: the notion that the strength of God often reveals itself in weakness and humility, in what is outcast and discarded. L’Arche residents also live the notion of diversity in a way which challenges our culture’s commitment to that virtue. This isn’t diversity born of beautiful and intriguing differences, at least not on the surface. The beauty of life at L’Arche appears through brokenness.

To say that the people at The Arch in Clinton, Iowa, are happy is too simple. Here is the truth I experienced: Spending ordinary time at The Arch is like spending time with family at its best. I’ve rarely been in a place where there is so much laughter and where the rhythm of life includes a real joy in that deceptive phrase, “the simple things of life.” I’ve rarely been hugged so fervently by strangers and enjoyed it.

And at the same time, running through my stay in Clinton was an underlying sense of grief which broke in on us again and again. I could see the struggle and loneliness left on people by the hardness of life, especially before they came to live in this place. And between us there were many moments of awkwardness, gaps in which we all were helpless as I failed to understand the words they tried to speak. The core members of The Arch don’t hide their pain in these moments, but they live with it gracefully, forgiving me for not getting it, forgiving themselves for not managing it, forgiving God for this design flaw.

And what relationship, what family, what workplace, doesn’t require such a habit of forgiveness? It’s this generosity of spirit towards one’s self and others which makes community here possible on a new level. It’s something that the core members teach every guest like me. And so I return to this theological mystery of beauty in brokenness, of strength in weakness, which is also a puzzle at the heart of what it means to be human, a puzzle which none of our education or technological advances will solve for us. The contemplative priest Thomas Merton put it this way: “I cannot discover God in myself and myself in others unless I have the courage to face myself exactly as I am, with all my limitations, and to accept others as they are, with all their limitations. The religious answer is not religion if it is not fully real.” Fittingly, as I left The Arch, the members of that community saw me off with a blessing, rather than the other way around.

[Group singing]

We’d love to hear your thoughts on today’s program. Contact us at onbeing.org. We’re making it easier for you to listen to Speaking of Faith. Subscribe to our podcast, which includes downloadable MP3s of our radio broadcast and many extras or sign up for our e-mail newsletter which links to our audio and includes my journal on each week’s program. Listen to Speaking of Faith in the way that best fits your life. Discover more at onbeing.org.

[Sound bite of Elvis Presley singing]

The senior producer is Mitch Hanley with producers Colleen Scheck and Jody Abramson and associate producer Jessica Nordell. Our online editor is Trent Gilliss with assistance from Randy Karels. This L’Arche pilgrimage was produced with the help of Brian Newhouse, Alan Stricklin, Scott Liebers, and Greg Thorson.

Audio of Jean Vanier came to us from the School of Theology at St. John’s University, in Collegeville, which presented him with the 2000 Dignitas Humana award.

Bill Buzenberg is our consulting editor. Kate Moos is the managing producer of Speaking of Faith. And I’m Krista Tippett.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.