Joel Marcus

The Jewish Roots of the Christian Story

New Testament writings about Jews may sound inflammatory in modern ears. A New Testament scholar with ties to both Judaism and Christianity helps us put these writings in context and look for meaning in the Passion that Hollywood and popular culture can’t convey.

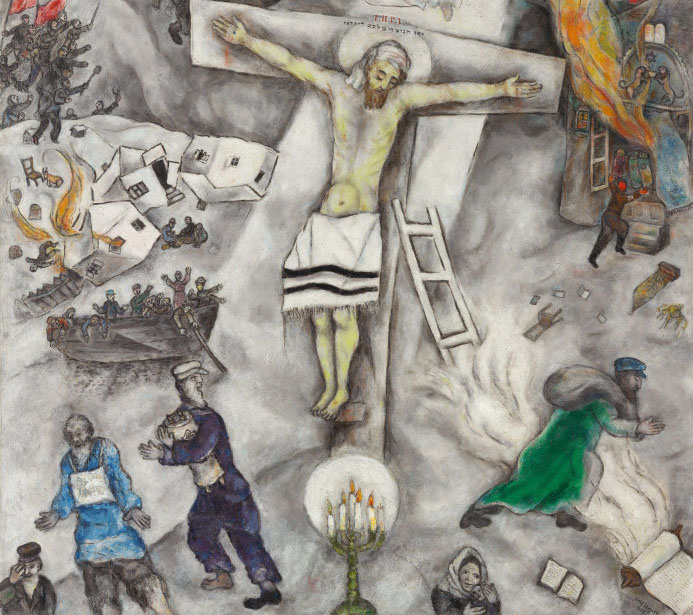

Image by Marc Chagall/Art Institute of Chicago.

Guest

Joel Marcus is an author and Professor of New Testament and Christian Origins at Duke Divinity School.

Transcript

March 24, 2005

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: This is Speaking of Faith, conversation about belief, meaning, ethics and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “The Jewish Roots of the Christian Story”. In our Christian influenced culture and especially perhaps in the season of Easter, it’s easy to forget the essential fact that Jesus and his early followers were Jewish. This hour we’ll explore the Jewish character of early Christianity. Doing so sheds new light on hard questions that are raised every generation. Is there an anti-Jewish strain at the heart of the Christian faith? What do the Biblical writings say and what do those writings mean both in the context of their time and in ours? This month Mel Gibson releases a new, less violent version of his movie, “The Passion.” In defending that film against charges of anti-Semitism last year, he insisted that his was a literal rendering of the Biblical story. But as we’ll explore, the New Testament itself does not offer a single, unified account. The four Gospels vary in how they detail and interpret the events before, during and after Jesus’ crucifixion. In places, the Gospels are also colored by an air of persecution real enough for the Christians of 2000 years ago who did, indeed, struggle to survive in the Roman Empire. In the millennia since then these same texts have been used by a Christian majority to support the persecution of Jews.

JOEL MARCUS: It wasn’t just Jews who killed Jesus, it was Jews and gentiles. It was humanity. It was us.

MS. TIPPETT: My guest today, Joel Marcus, has a rare perspective from which to consider all of this. He’s a professor of New Testament and Christian origins at Duke University. He was raised in a secular Jewish home. In the heady mix of politics and spirituality in Berkeley, California, in the 1960s. He became a writer and a religious seeker. He read the Bible for the first time all the way through because he found so many allusions to it in great literature. And what began as a literary interest became a passage of faith. In the introduction to his 1995 book Jesus and the Holocaust he writes, quote, “In my early 20s I became a Christian and later a New Testament scholar, but I continue to view myself as a Jew. This opinion is shared by Jewish law,” unquote. Here’s Joel Marcus.

DR. MARCUS: After, you know, even these 25 or 30 years after becoming a Christian, I think I’m still negotiating those two sides of myself. And my work is one way in which I do that because it is about the New Testament, but it emphasizes strongly the Jewish roots of Christianity.

MS. TIPPETT: And I want to get into this whole subject of Jewishness and Jesus and Judaism and Christianity in the New Testament. And, you know, one reaction I have as it’s become this big controversy is to be reminded of the simple fact that Jesus was Jewish, as were all of his apostles.

DR. MARCUS: I think, by the way, that’s one of the bad things about the Gibson movie, you know, just parenthetically. But it seems to me that the opponents are identifiably Jewish whereas Jesus and his disciples aren’t. Basically what you have in the New Testament is an intramural argument, an argument that is within the walls of Judaism. And, you know, Christianity started really as a sect within Judaism and, you know, it’s referred to as a sect in the book of Acts. You know, so within the first century of the church’s existence, you have this switch from a movement that is entirely Jewish to one that is mostly Jewish but with a minority of gentiles. And then the thing began to tip the other way. Though it’s still true that for hundreds of years there remained a lot of people who were Jewish and even Jewish in terms of Jewish law who observed the halakhah, the Jewish law, and who yet believed in Jesus as the Messiah. I mean, Jesus’ own brother, James, was the leader of the Christian church in Jerusalem until he was martyred in the 60s of the first century. He seems to have been a Torah-observant Jew.

MS. TIPPETT: Right, a very Jewish figure, isn’t he? Yeah.

DR. MARCUS: Yeah. And he was known for his piety. And, you know, according to Josephus, the Jewish historian, many Jews were upset when he was martyred.

MS. TIPPETT: Let’s talk about some of the specific kinds of language that are in the New Testament — it’s different in the different Gospel accounts — and how some of that language made its way in.

DR. MARCUS: Yeah. Well, I think the most striking example of this way in which language reveals what was happening sociologically in the church is the way in which the different writers used the word `Jew.’ And the most striking example is in the Gospel of John where the term `Jew’ becomes usually a negative term. And it becomes a technical term for the enemies of Jesus. Now I think that that language reflects a later stage in the development of Christianity. I don’t think that it comes primarily from Jesus’ own time.

MS. TIPPETT: Just to remember also that these Gospels were written decades — I mean, say the Gospel of John was written decades after the events, which is how that could happen, right?

DR. MARCUS: Right. Yeah. John was written — the best guess is probably AD 90 or AD 100, so that’s 60 or 70 years after Jesus had lived. And one of the things that had happened in the interim was that the Jews of Palestine, the Jews of Israel, had risen up in revolt against the Romans. That revolt was eventually crushed, the temple was burned and razed to the ground in AD 70. So the Jews of Palestine had suffered this massive blow, and in the aftermath of that they pulled themselves together, and as part of their effort to bring the people together, they tried very hard to define who was Jewish and who wasn’t Jewish. And one of the conclusions that they came to was that it was no longer possible to be a good Jew and a Christian at the same time. And so I would see this very pointed language about, quote, “the Jews” in John’s Gospel as a response. You know, there are some very sharp things including, Jesus in John says that the Jews are of their father, the devil. And so, I mean, this is the sort of language that people develop when their parent group rejects them.

MS. TIPPETT: New Testament scholar Joel Marcus. Here’s an excerpt from that vitriolic passage from the Gospel of John, perhaps the most hateful exchange between Jesus and Jewish leaders recorded in the New Testament. In fact, this passage is set in the temple where Jesus is teaching. He’s speaking to an audience of scribes, pharisees and, the text says, Jews who believed in him.

READER: From the Gospel of John, chapter eight. “They said to him `We are not illegitimate children. We have one father, God himself.’ Jesus said to them, `If God were your father you would love me, for I came from God and now I am here. Why do you not understand what I say? It is because you cannot bear to hear my word. You are of your father, the devil, and your will is to do your father’s desires. He was a murderer from the beginning.'”

DR. MARCUS: I mean, these are, you know, really horrible things, especially if abstracted from this original context. I think the author of the Gospel of John probably is a Jew himself. And that Gospel shows more knowledge of Judaism actually than any other Gospel, and yet it also has the most pointed comments about Jews. So I think it’s, in a way, an argument that’s going on within the Jewish community. And I guess, you know, one of my deepest feelings is that we can’t just take these things that come out of a situation in which Christians were being persecuted by Jews and then apply them to our own situation in which, for the past 16 or 1700 years, it’s been almost entirely the other way around. And I like to compare it to telling an ethnic story. Say, telling a Jewish joke. You know, it’s very different depending on who’s telling the joke and to whom. If it’s a Jew telling a Jewish joke to other Jews, then it’s all in the family and it’s self-criticism. And that may be in a way the way some of this vituperation against Jews in the New Testament starts. It starts within the family. But that becomes very different when it’s picked up by people who are not Jewish. You know, just as a Jewish joke becomes quite different if, say, it’s a gentile telling a Jewish joke to other gentiles. You know, then it becomes a joke about what, you know `those other people do,’ and then it can become very much nastier.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. And as you said, the way that history progressed — I mean, within a couple of centuries Christians had become the one — Constantine had converted, and Christians were the powerful group.

DR. MARCUS: Right. Well, and I think, you know, the problem is a lot of our canonical documents were formed in this initial situation in which Christians were the minority group. Now they’re the majority, at least in a place like America, and yet they still have this sort of persecuted mindset that, you know, leads them to see hostility on every side, even sometimes when it’s not there.

MS. TIPPETT: You mean now, or in the way the stories have come down to us?

DR. MARCUS: Well, it’s the way that the stories have come down, but I think that it’s also the way in which the stories are perceived. You know, that even though on a rational level most Christians in this country know that they’re members of the dominant group, I think lurking in the back of their mind is the idea that Christianity is a persecuted religion. It can, again, become a persecuted religion, or even in some groups that if you’re really a Christian then you will be persecuted. So I think that this sort of consciousness of persecution, you know, just because it is so deeply ingrained in the sort of founding documents, it’s rumbling around there in the background and it may lead us to see persecution even sometimes when it’s not there.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, that’s a really interesting thought, that somehow Christians are shaped by these texts and that there’s a disconnect between the reality of the text and the reality of our times. Let’s talk about you as a New Testament scholar. All right, so one of the interesting pieces I’ve read recently is Raymond Brown’s famous article about anti-Judaism in the New Testament. He was this great scholar of John. There are places also in the Gospels, aren’t there — maybe not so much in the Gospel of John, but in the other three, Matthew, Mark and Luke — where their relationship is a bit different, where it’s not all-out hostility.

DR. MARCUS: Well, yeah. I mean, for example, there are passages such as one in Luke’s Gospel in which Jesus is warned by the Pharisees, who are usually the people that he clashes with, against Herod — Herod Antipas — who was the leader of part of Palestine at the time. And so that seems to be sympathetic. I imagine that Pharisees themselves were probably divided on their reaction to Jesus. And that’s even revealed in the Gospel of John, you know, because there is this one character, Nicodemus, who is described as a Pharisee and a leader of the Jews, and yet he’s sympathetic to Jesus. And in the end I think he becomes a follower of Jesus. And earlier on, the book of the Acts of the apostles describes Jewish leaders who didn’t want to take a hard line against Jesus. And, for example, Gamaliel, who was Paul’s teacher, he counsels other Jewish leaders against banning the Christians. And he basically says, `Look, if this movement is of God, then it will continue and prosper. And if not, it will whither away.’

MS. TIPPETT: Raymond Brown also describes one of the things that happened very early on is, after the events of Jesus’ life and death, that Jews began to interpret those things in light of Old Testament prophecy, or the prophecy of the Hebrew Bible, especially Isaiah, Jeremiah. And in something I read that you wrote — you weren’t talking about this subject — but you described reading Isaiah, again maybe as you were first becoming interested in Christianity, and being struck by those parallels. I mean, it sort of was interesting to me in this context that you personally, as a modern Jew who had learned about Christianity, also had this experience of seeing the parallels.

DR. MARCUS: Yeah, well, I think, in part, I relived the experience of the earliest church in a very visceral way. Now, I didn’t grow up knowing Isaiah, but as a Christian I started reading, you know, the Old Testament very intensively. And as I’ve described, that’s part of the way that I became a Christian, through reading the Old Testament and then going on to the New Testament. But when I got to Isaiah chapter 53 and this famous passage about the Lord’s suffering servant who has been smitten for our offenses and by whose wounds we are healed, I was very struck by this, and it seemed to me to be similar to what the Christians were saying about Jesus. And then, of course, that passage is used in the New Testament, and it’s one of those passages that Jews use to try to convince their fellows Jews that Jesus was the Messiah.

MS. TIPPETT: New Testament scholar Joel Marcus. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today we’re discusing the complex and ambivalent relationship the earliest Christians had to their Jewish heritage, specifically whether the early Christians considered Jews to be their enemies and, perhaps most importantly, whether the New Testament is anti-Semitic. Here’s a reading from the passage Joel Marcus just mentioned, the prophecy of Isaiah about a servant of God who would suffer for all people.

READER: From the 53rd chapter of Isaiah. “Surely he has born our griefs and carried our sorrows, yet we esteemed him stricken, smitten by God and afflicted. But he was bruised for our iniquities. Upon him was the chastisement that made us whole, and with his stripes we are healed.”

MS. TIPPETT: It was interesting to me, you point out that there have been many Jewish artists and authors — I think you mentioned Chagall and Chiam Potok — who’ve taken that image of the suffering servant and held that together with a strong Jewish identity, have found that to be a powerful image that brings them closer to Christians.

DR. MARCUS: Right. Yeah, I think that’s interesting. And, you know, for example, Marc Chagall’s famous painting of the “White Crucifixion,” the very powerful painting which has an identifiably Jewish Jesus — he has a Jewish tallit, you know, a prayer shawl, wrapped around his body — he is portrayed crucified on the cross, but all around him are these images drawn from the Holocaust which was — I think the painting comes from the late ’30s — images of pograms, images of shetelas in flames. So there is this connection that he’s making between Jesus’ suffering and the suffering of Jesus’ fellow Jews in the 20th century. Now, you know, I don’t think he was a Christian. I think partly what he’s saying through that painting is Christians want to bang on about Christ’s suffering. You know `Well, this is the way in which Christ is suffering, through the people that, you know, he belonged to.’ `This is the way that he’s suffering in the 20th century.’ So, you know, it’s a very fascinating kind of juxtaposition that employs, you know, the central icon of Christianity but uses it to talk about the suffering of the Jewish people. And I think there is a relationship actually between that and the way in which the New Testament writers, for example, use a passage like Isaiah chapter 53, which is this passage about the Lord’s suffering servant, to speak about Jesus. Because I think that you can make a good case that originally in its Old Testament context, and certainly as interpreted by many Jewish interpreters subsequently, that passage refers to the suffering of the Jews. You know, Israel is God’s chosen servant who suffers for him. And then the Christians applied that passage to Jesus. So it’s quite similar in a way to Chagall’s juxtaposition of Jewish suffering, the suffering of the people of Israel, and Jesus’ suffering.

MS. TIPPETT: So again I just want to point out the contrast we’re drawing here is between a dramatized version of Jesus suffering, which somehow suggests that Jesus suffered because of the Jews, and an interpretation of that event that says that that part of the dynamic which had to do with history is not the point.

DR. MARCUS: Yeah, but I think I would like to point out, you know, I don’t think that we can exculpate — pronounce “not guilty” — the New Testament entirely. Because I think already within the New Testament, in the development of the Passion narratives, you do see this tendency to make the Jewish authorities more and more guilty of Jesus’ death and the Roman authorities less.

MS. TIPPETT: The Romans are good guys.

DR. MARCUS: And most of the Romans are really nice guys, and most, with a few exceptions, most of the Jews are really bad guys, with a few exceptions. But I think, you know, he’s extended something that is already there in the New Testament. And I don’t think that historically, you know, from external sources, Pilate doesn’t seem to have been a nice guy. And I think it’s understandable, though perhaps not entirely excusable because, after all, as the Christian movement was moving out into the gentile world which was ruled by the Romans, the Christians were interested in showing to the Romans that actually, in spite of the fact that Jesus had been crucified — which was a Roman punishment, not a Jewish punishment — Romans, when they really looked into this movement thought that it was OK. And within the Gospels themselves, especially the later Gospels, especially in the Gospel of Luke, as a matter of fact, Roman authorities keep emphasizing that Jesus is innocent. I mean, that’s implicit in all the Gospels, but it’s most explicit in Luke. So, I mean, that’s part of a Christian outreach to the gentile world that was ruled by the Romans.

MS. TIPPETT: Sixty, 70 years later, again, after the event.

DR. MARCUS: It is. That’s right. It’s after Jesus’ own time. You know, I don’t want to say that there is none of this sort of shaping of the history in a way that reflects a hostility to Jews. I don’t want to say that there’s none of that in the New Testament. And I’m not sure if I want to call that anti-Semitism because that’s sort of a technical term that has, you know, different implications of its own. But there is a growing sort of tendency to blame Jews more and blame gentile authorities less. And it makes me very upset actually to hear that sort of passage fixed upon by Christian preachers.

MS. TIPPETT: That sort of passage — which passage?

DR. MARCUS: Well, the sort of passage that shows the Romans being nice guys and the Jews being bad guys. You know, I’ve heard some things said in churches that were picking up on these more pointed comments about Jews, and they make me very uncomfortable. You know, they make me, as a Christian person of Jewish parentage feel like walking out. It’s very upsetting when that happens. And I guess that’s why it seems to me that it’s so important to contextualize these texts and to see what was the historical background and to point out, as you keep saying, their situation was quite different from our situation. And so, you know, you can’t just treat these texts as if they had dropped from the sky yesterday with timeless truths so that the word `Jew,’ as used in the New Testament, means exactly what people today mean by the term `Jew.’

MS. TIPPETT: Joel Marcus is professor of New Testament and Christian Origins at Duke Divinity School. Marcus mentioned that Jewish thinkers have found material for reflection in the Christian story. The late author Chiam Potok took up the mystery and ambivalence of that connection in his novel My Name is Asher Lev. The protagonist is a contemporary observant Jew who creates a sensation in the art world with a painting called “The Brooklyn Crucifixion.” Here’s a reading from that novel that conveys the painter’s own astonishment that this has become his subject. It also echoes Joel Marcus’ sense of the meaning of the Passion as an event that encompasses all human suffering. Chiam Potok’s protagonist is focused on the suffering of his own 20th-century Jewish parents. He writes: “I painted swiftly, in a strange, nervous frenzy of energy. For all the pain you suffered, my mamma. For all the torment of your past and future years, my mamma. For all the anguish this picture of pain will cause you. For the Master of the Universe, whose suffering world I do not comprehend. For all these I created this painting — an observant Jew working on a crucifixion because there was no aesthetic mold in his own religious tradition into which he could pour a painting of ultimate anguish and torment.” From Chiam Potok’s 1972 novel My Name Is Asher Lev. This is Speaking of Faith. After a short break, more of my conversation with New Testament scholar Joel Marcus on “The Jewish Roots of the Christian Story”. On our website at speakingoffaith.org, you’ll find full quotation and references for all the readings in today’s show, also an image of Chagall’s “White Crucifixion” and a link to a classic essay by a New Testament expert, Raymond Brown, “The Narratives of Jesus’ Passion and Anti-Judaism.” This essay gives insight into the way scholars and theologians have discussed this issue for many generations. And while you’re at speakingoffaith.org, you can also sign up for our e-mail newsletter. I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us.

[Announcements]

Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, conversation about belief, meaning, ethics and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Each week we take on a different theme asking how religion shapes ideas in the news and in everyday life. Today we’re exploring the relationship between early Christianity and Jewish tradition. We’re asking whether the New Testament is inherently anti-Semitic, a question some critics feel has been heightened by Mel Gibson’s movie “The Passion of the Christ,” which is being re-released this month. My guest, Joel Marcus, is a Christian who, like Jesus and the first Christians, was born Jewish. His work as a New Testament scholar at Duke Divinity School is focused on the Jewish background of Christianity. He’s been describing some of the sociological and historical background that influenced New Testament writings about the Jewish opponents of Jesus. For example, the earliest Christians grounded their faith in Jewish scripture, what Christians call the Old Testament, and found there a framework for forming their beliefs.

DR. MARCUS: The Old Testament is very important in shaping early Christian theology, including the Passion narratives.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. Say some more about that.

DR. MARCUS: Yeah. Well, the Passion narratives constantly hark back to the Old Testament either explicitly or implicitly. For example, in the Gospel of Mark, especially in these narratives about Jesus’ death, there’s all sorts of allusions to the Old Testament, including, you know, Jesus’ last word on the cross — his one word on the cross actually in the Gospel of Mark and in Matthew is “My God, My God, why have you forsaken me?” which the Gospels give in the original Aramaic. Now, that is from one of the psalms from the Hebrew Bible, Psalm 22. So even, you know, at the very point of death Jesus was quoting the Old Testament. That’s how visceral it was for him. You know, he lived in the Old Testament. And I think, you know, part of what happens in the Gospel Passion narratives is that they develop on the basis of the Old Testament. People remembered things that had happened to Jesus and things that he had said that seemed to refer to the Old Testament, and then they went back to the Old Testament, like this passage from Psalm 22, and they found other things that seemed to refer to Jesus in their minds and that becomes part of the Gospel narrative.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, in this context of considering whether the message of the Passion story is somehow anti-Jewish or anti-Semitic in the term we use in our time, they were mining Jewish scripture to find meaning in those events. Do you think it’s important to state…

DR. MARCUS: Yeah. Right. They were mining Jewish scripture, which often is very critical of itself. You know, so that again goes back to, you know, the prophets are constantly castigating their own people. And a lot of what happens in early Christianity is that early Christianity adopts this prophetic sort of self-criticism, but it turns it against that portion of the Jewish people that didn’t accept Jesus. And then, as I said earlier, that, well, if you know that this is a sort of intramural argument, then it has one sort of sound, but then if you think centuries later that it’s an argument against those people out there who aren’t part of our group — that is, those Jews — then that sort of prophetic invective can become a lot nastier. It can be heard in a more nasty way.

MS. TIPPETT: Jesus’ utterance of the first words from Psalm 22 in his dying moments, as recorded in two of the Gospels, is a powerful expression of immersion in the Hebrew Bible. The words would evoke the entire psalm for many Jewish listeners. Here are the first 11 verses.

READER: “My God, My God, why have you forsaken me and are so far from my cry and from the words of my distress? Oh, my God, I cry in the daytime but you do not answer, by night as well, but I find no rest. Yet, you are the Holy One, enthroned upon the praises of Israel. Our forebears put their trust in you. They trusted, and you delivered them. They cried out to you and were delivered. They trusted in you and were not put to shame. But as for me, I am a worm and no man, scorned by all, despised by the people. All who see me laugh to scorn. They curl their lips and wag their heads saying, `He trusted in the Lord, let Him deliver him. Let Him rescue him if he delights in Him.’ Yet you are he who took me out of the womb and kept me safe upon my mother’s breast. I have been entrusted to you ever since I was born. You were my God when I was still in my mother’s womb. Be not far from me, for trouble is near and there is none to help.” From Psalm 22.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, “The Jewish Roots of the Christian Story”. My guest, Joel Marcus, is the author of a book entitled Jesus and the Holocaust. I asked him whether the writing of this book was a personal attempt to reconcile some of the history of misunderstanding in the Jewish/Christian relationship.

DR. MARCUS: Yeah, I think I was, you know, working these things out on a kind of both a visceral, emotional level and, you know, maybe an intellectual level. I was, I guess, just concentrating because these were originally written for a Good Friday service where I was asked to do the three-hours homilies, and the homilies that are done in the Episcopal tradition between 12 and 3 on Good Friday.

MS. TIPPETT: And Good Friday is the day on which Christians remember the crucifixion.

DR. MARCUS: They concentrate and remember and relive even the death of Jesus. And the particular year in which I was asked to do these homilies was in 1995. So that was exactly 50 years from the end of World War II, the end of the Holocaust. So I just didn’t think that I could talk about the death of Jesus without talking about the death of what Paul calls his “brothers and sisters according to the flesh,” you know? So I took those two examples of innocent suffering and I correlated them to each other. So yeah, I think I was trying to work things out and to show that there was this intensely close relationship between those two things. So, I mean, I don’t think that any human being suffers in a way that is apart from the suffering of Jesus. And that includes Jews. So that somehow this mystery of innocent suffering that we see, for example, in, you know, men, women and children marched into the gas chambers, it’s the same mystery that we see in the innocent and righteous Jesus crucified and suffering and going through despair on the cross.

MS. TIPPETT: What were some other places your thinking took you as you wrote those sermons that maybe surprised you?

DR. MARCUS: Well, I guess one of the places that I was taken by thinking about this whole question of Jesus and his Jewish background and suffering — I guess thinking about those things really did take me back powerfully to my Jewish roots in a kind of surprising way. And while I was writing the book, I went to Prague and I walked through the Jewish cemetery there, which is a very evocative place. It’s an old cemetery. It hasn’t been used for several centuries, so it’s from the Medieval and early modern Jewish community of Prague. And I felt a tremendous sense of identification with this people.

MS. TIPPETT: The Jewish people?

DR. MARCUS: Yeah, with the Jewish people and with these Jews in Prague whose descendants then, most of them probably were wiped out in the Holocaust. But on one of the two occasions in which I walked through that graveyard, I walked through with an older friend who is also a Christian scholar who has meant a lot to me, who I think, you know, empathizes deeply with my being Jewish and being Christian and my way of negotiating that. And so I felt both a strong bond with him and with the Christian side of myself and with the Jewish side of myself as epitomized in that graveyard in Prague. And, you know, I had the same feeling a few weeks ago when I was in Jerusalem and, not the first time, went to the Western wall, the so-called “Wailing Wall,” and just saw those stones that had been there for 2,000 years, stones that have seen so much bloodshed and so much Jewish blood shed over the years and to which Jews keep returning because they’re the one remaining remnant of the temple. And I just felt this strong sense of continuity with that whole history.

MS. TIPPETT: And that is a very Jewish stance also to experience that history, to be present.

DR. MARCUS: Yeah. Of course, it is. And again, it’s part of even the background to the Passion narratives because the last supper was, or at least is presented by the Gospels as being a Passover Seder. Well, according to John, it’s the day before Passover. But even if it wasn’t a Passover Seder, it was still during Passover week, and that week is imbued with these memories of ancient Jewish history, and especially the liberation from Egyptian tyranny. And as part of the Passover Seder, a saying of Rabban Gamaliel is recalled that says that in every generation a Jew should regard himself, or herself, as if he personally came out of Egypt. You know, it wasn’t only our forefathers that God redeemed, but us ourselves. And I think that that forms the background to what Jesus did in sharing bread and wine with his disciples and saying that they should do this in memory of him. You know, memory in Judaism isn’t just casting your mind back, it’s reliving the events. And he was both reliving the events of, you know, his people’s redemption from slavery and also, as the Passover Seder does do, looking forward to the redemption to come. You know, the Messianic redemption, which I believe that he thought was intimately wound up with his own ministry. So this whole dynamic of remembering and reliving God’s redemption of old in order to look forward to the redemption coming in the future is, as you say, it’s very Jewish, and it’s central to Christianity as well.

MS. TIPPETT: New Testament scholar Joel Marcus. The evocative Jewish language of remembrance only occurs in a letter of the apostle Paul. Paul’s letters are the New Testament books written closest to the actual events of the Passion, and he himself was a former Pharisee. Here’s that section of his teaching about the last supper of Jesus.

READER: “For I received from the Lord what I also deliver to you, that the Lord Jesus on the night he was betrayed took bread. And when he had given thanks, he broke it and said, `This is my body which is given for you. Do this in remembrance of me.’ In the same way, alsothe cup after supper, saying `This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this as often as you drink it in remembrance of me. For as often as you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes.'” A reading from St. Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians.

MS. TIPPETT: You also, as you are reflecting on the Passion, you speak about that moment — and I don’t know how many of the accounts it’s in — where Jesus says “Father, forgive them. They know not what they do.”

DR. MARCUS: Right. Yeah, it’s only in Luke.

MS. TIPPETT: OK, it’s only in Luke, but it brings a new idea into the story really in terms of the relationship between Jesus and the Jews.

DR. MARCUS: Well, yeah, I think that’s a very important verse to emphasize in the present context. You know, it’s central to the Christian story that Jesus forgave those who executed him. And I think, you know, that’s not just something that he said, it’s a logical extension to say that that applies today after all this, you know, history of Christians persecuting Jews, it applies first and foremost to his own people. So I think forgiveness was central to his ministry, and that’s what that verse epitomizes.

MS. TIPPETT: I’d like to read to you a passage from your book Jesus and the Holocaust just because this was an illustration of some of the very troubling questions that were raised for you, and it was a really striking passage for me as you, as a Jewish Christian, thought about what the connection might be between Jesus and the Holocaust. And you wrote, “If the earth quaked at Jesus’ death, why did it not tremble at the death of six million of his fellow Jews? If in the Old Testament it opened up to swallow Korah, Dathan, and Abiram for offering strange fire on the alter of the Lord, why did it not open up to swallow Hitler, Eichmann and Himmler for creating at Auschwitz a strange fire whose flames leaped up to heaven?”

DR. MARCUS: Yeah. You know, I think anybody who presumes to give an answer to that question is a dangerous person because there is no answer to that question. And, you know, just as in the Book of Job in the Old Testament, you know, we see that Job’s friends who all have, you know, very neat solutions to the problem of evil, they’re in the end rebuked by God and the person whom he acclaims is Job, you know, who just keeps asking `Why?’ You know `Why am I suffering so?’ And I guess for me the comforting thing is that, you know, these sort of questions that I asked in that book about, you know, why didn’t God intervene, those are the same questions that Jesus gives voice to in these scenes in Matthew and Mark on the cross, you know, when he asks God why he has forsaken him. You know, he existentially feels forsaken by God. So I guess for me one of the most comforting things is that when I go through, you know, that sort of questioning — `Where is God?’ You know, `How can we say that there’s a God in a world that sometimes seems so terrible?’ — I’m not doing anything un-Christian by raising that question. As a matter of fact, I’m doing the same thing that Jesus did on the cross.

MS. TIPPETT: Raising the question.

DR. MARCUS: Raising the question. And even if I experience despair, you know, that also is not strange to Jesus. Now, I mean, that is strong medicine, though, and, as a matter of fact, both Luke and John changed Jesus’ last words, you know, so that in both of those other Gospels his last words become much more sedate and calm and triumphant. And I understand why they did that. You know, they were probably directed, as Mark’s and Matthew’s Gospels were, to people who were suffering. And I think probably Luke and John thought that, in order to strengthen Christians to endure suffering, they needed an example of a Jesus who triumphed over suffering, which I think he ultimately does in Mark and Matthew also, but not in the crucifixion scene itself. You know, he triumphs through the resurrection. But, you know, he experiences real existential despair at the cross. Now, I don’t think that that means that Christianity says that suffering is good in and of itself, you know, because that would be masochism. But I think what it says is that our suffering and our despair can become the arena in which God’s power is revealed.

MS. TIPPETT: In your book Jesus and the Holocaust when you visited the Prague cemetery, you referred to your friend who you mentioned to me a moment ago, as “a gentile Christian friend,” which is interesting that you use that phrase, which I really think of as a New Testament phrase.

DR. MARCUS: Well, and I’m married…

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, you’re married to a gentile person?

DR. MARCUS: I’m married to a gentile Christian friend also. Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: I mean, I wonder if you think your experience of Holy Week is any different because you are a Jewish Christian and not a gentile Christian, like most American Christians?

DR. MARCUS: Yeah. Well, let me first say that, you know, it’s quite important to me to be part of a church that, you know, includes both Jews and gentiles. And, you know, I’m not one of these people who thinks that Jewish Christians should worship by themselves or try to get gentiles to observe Jewish laws. You know, it’s very significant to me that, you know, it’s within the church that some of these ethnic barriers come down. And, you know, for example, it was within the church that I first really experienced a sort of communion and oneness with African-American people. Well, I grew up in a segregated white suburb of Chicago, so I didn’t know many African-American people. I went to college, and I got to know some African-Americans. But it was only within the church that it seemed to me that, you know, these barriers of suspicion on both sides and, you know, feeling like people are so different came down. And they came down for me when I was going to a little black Pentecostal church in Staten Island where the people who went to that church were very different from me in terms of their upbringing and their experiences, and yet, you know, we were all members of a family together. You know, they called me “Brother Joe,” and I was just, you know, one of the Christian brothers who went to the church, and that was really wonderful. So I think, you know, I do value a lot within the church that, you know, at its best it is a place where people from different ethnic groups come together, including Jews and gentiles. I think my experience of Holy Week, I think it is affected by my being from a Jewish background partly because I’m aware. You know, at the back of my mind there is this awareness that Holy Week has been a dangerous time for Jews. Because with the telling of the story of Jesus’ death and what led to it, a lot of people down through the centuries have gotten the impression that is was Jews who were responsible, Jews killed Christ, and, you know, they’ve killed Jews in return. And I’m acutely aware of that history. And so I guess one thing that my being Jewish means during Holy Week is that I’m very much on my guard and sensitive if anybody sort of strays near that sort of charge. And so, you know, I always listen for, in the Good Friday homilies, you know, people are going to make the point that it wasn’t just Jews who killed Jesus, but it was Jews and gentiles, that it was really humanity. You know, that it was us, you know, as this famous German hymn says, “I crucified him.” So, you know, I want to hear the preacher making that point. And if I don’t hear them making that point, I am upset. So I guess that’s one of the main effects that it has. I guess also, frankly, you know, just having, you know, spent a sabbatical, spent a year in Israel and having been back there many times, I can see these places very vividly in my mind as the story’s being told. And it all becomes very real because, you know, at the same time it’s a timeless story, and yet it’s a story that is connected to a particular place in a particular time.

MS. TIPPETT: Joel Marcus is professor of New Testament and Christian Origins at the Duke University Divinity School. His books include commentaries on the Gospel of Mark and Jesus and the Holocaust: A Story of Suffering and Hope. Surely there is possibility for good in the questions raised by Mel Gibson’s movie version of the Passion, but the good will be found in taking those questions back to the Biblical stories themselves and in reflecting on the ways these stories have shaped the 2,000-year history shared by Christians and Jews. It is a history both appalling and intimate, and it is still being written in our time.

We’d love to hear your thoughts on this program. Please send us an e-mail through our website at speakingoffaith.org. There you’ll find in-depth background information about “The Jewish Roots of the Christian Story”, as well as an image of Chagall’s “White Crucifixion.” There’s a link to the classic essay by the New Testament expert Raymond Brown, “The Narratives of Jesus’ Passion and Anti-Judaism.” You can also sign up for our e-mail newsletter and get my weekly reflections, program extras and a preview of next week’s show. That’s speakingoffaith.org.

[Credits]

I’m Krista Tippett. Next week, theodicy and tsunami. Please join us.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.