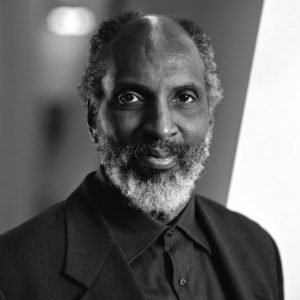

john a. powell

Opening to the Question of Belonging

“Race is a little bit like gravity,” john powell says: experienced by all, understood by few. He is a refreshing, redemptive thinker who counsels all kinds of people and projects on the front lines of our present racial longings. Race is relational, he reminds us. It’s as much about whiteness as about color. He takes new learnings from the science of the brain as forms of everyday power. “We don’t have to imagine doing things one at a time,” he says. “It’s not, ‘how do we get there?’ It’s, ‘how do we live?’”

Image by Vonecia Carswell/Unsplash, Public Domain Dedication (CC0).

Guest

john a. powell is director of the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society and professor of Law, African American, and Ethnic Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. He previously directed the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at Ohio State University and the Institute on Race and Poverty at the University of Minnesota. He is the author of Racing to Justice: Transforming our Concepts of Self and Other to Build an Inclusive Society.

Transcript

john a. powell: As a country, we really don’t like talking about race. And part of this is because it’s a hard conversation, and oftentimes, we do it badly. And it’s like if you have a party, and you invite people to your party, and it’s a bad party; then you say, “I’m going to have another party next weekend.” It’s like, “I’m sorry.”

[laughter]

“I’m out of town.” But it’s like, “Come; let’s talk about white privilege and about…”

[laughter]

“I think I’m busy.”

[laughter]

Ms. Tippett: john powell says that race is “a little bit like gravity” — experienced by all, understood by the few. He opens the question of race into the question of belonging. He’s a wise, redemptive thinker on the frontlines of our current racial longings. john powell offers new learnings from science as forms of everyday power and brings a refreshing, human calling into perspective.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Ms. Tippett: john powell is a legal scholar and director of the Haas Institute at the University of California, Berkeley. He’s previously taught in Africa and across the United States. I spoke with him in 2015, before a live audience at the On Being Studios on Loring Park in Minneapolis.

Ms. Tippett: Where I’d like to start, I think, is — here are some things you’ve said about race: “Race is a little bit like gravity”; “Race is not just an external trait; it is also an internal process that can create and destroy internal and external worlds.” I would like to start, though, with just posing that question to you, the question of what race is and how you would begin to answer that question through the story of your earliest life. And your answer might include the spiritual aspect of that, as well as the practical.

Mr. powell: Well, first of all, good morning, and thank you for having me. Like most of our lives, we have many stories. And sometimes, we wonder if they’re true, even though we live them, because we keep making stories. We keep adding to our stories.

I come from a large family. And my father and mother were sharecroppers in the South. My father’s a Christian minister. He’s celebrating 95 this year. He really is an amazing person, as is my mom. And if I were to chronicle their lives, it would sound like, wow, what a hard life. Having lost his mother at a very early age, he was forced to leave school in the third grade to start working full-time, and worked ever since then. He’d lost limbs. He’s legally blind.

I remember being 12 years old in Detroit: He, like most people from the South, he did everything himself. So, he’s fixing a furnace, and it blew up. It cindered all the hair on his body, so he had burns all over his body. We’re driving around the city, trying to find a hospital that would accept a black man, and getting turned away, and then going to the next hospital, getting turned away. And as I tell these stories, again, they are sad stories. But when you meet my dad, he just radiates love. He literally attracts people. And he has this quality of appreciating life, and I feel like a little of that has fallen to me.

My interest in social justice — I don’t know where it comes from really, except, I would say, part of it’s the family, part of it’s — to me, it’s an expression of caring, just caring about people and saying that you are connected to people and other life forms, and then giving it voice. And I think, if we do that, we not only lean into what’s called social justice, but deeply into spirituality and religion, as well.

Ms. Tippett: This moment we’re in now, writ large — one of the things you’ve said is that race is in the DNA of this country, but it’s also everchanging and evolving; and that right now, in our neighborhoods and our world, there are contradictory things happening. So, with a wide lens, talk about the contradictory things you see happening.

Mr. powell: Well, race is actually — it is like gravity. And I like to use that metaphor, because — what scientists say is, all of us have weight. And so we would think we might all be experts in gravity, but scientists say there are probably 12 people in the world that really understand gravity. And I would say, there’s only a few more in the world that understand race, but it’s actually incredibly complex, once we start peeling it back.

I’m old enough to have been born “colored.” And then I became a “negro.” And then I became “black.” And then I became “African-American.” And then I became “afro.” And people are just, now, confused — “So, what are we?” And part of the confusion — and each of those terms are significant. But also, race is deeply relational. And it’s interesting, if you go back and think about how “whiteness” was early defined in America, it was defined largely as “not-black.” And so, James Baldwin reminds us that blackness is in whiteness; that whiteness is in blackness — that these are these complicated dances that we, most of us, don’t understand.

Ms. Tippett: And I fantasize about having entire discussions where we didn’t use the word “race,” where we were talking about all the things that are actually involved. And I think one reason I feel it doesn’t work as shorthand — like a lot of words we need; like “love” is another one we’ll probably — it doesn’t — we’ve ruined it. But we tend to take the word “race,” in our imaginations, to be something that is about people of color. And a point that’s so important in your writing is the question of whiteness; that we all have race.

And you actually gave me — the language of white privilege — an analogy that you gave that was so helpful to me. You said, “Whiteness is like the invisible presence of the narrator in a story told from the third person point of view.” That’s very helpful for me, to imagine that.

Mr. powell: So one of the things about language is, language is never quite right, but neither is not-language. And what we’re finding now, in the last 30 years, is that much of the work, in terms of our cognitive and emotional response to the world, happens at the unconscious level. When we moved from race and the discussion of race, it was partially because we were trying to move from a Jim Crow era and a white supremacy era. And we said, “OK, that’s bad; so to notice race is bad, so let’s not notice it anymore.” But it was still deeply embedded in our biology, in our structures, in our arrangements. And the unconscious was saying to the conscious, “You can do whatever you want to. We’re going to keep noticing race.”

[laughter]

And so it still responds to race in some pretty powerful ways.

The other thing is that because we are so powerfully rooted to the notion of individuality, in some ways race affronts that. But the real affront is the whole notion of individuality. Individuality, as we think of it, is actually extremely problematic.

Ms. Tippett: Well, see — yeah, and you make this really fascinating point that — you say that there are two parents to the way we are now; the way we grapple with race, among other things. And one is slavery. Get that. And the other is the Enlightenment and that, in fact, it’s from the Enlightenment that we inherited this idea that the conscious mind could know everything; that we could be reasonable.

Mr. powell: That’s the American exceptionalism. So the United States became extremely, extremely attached to the notion of individuality and independence. Now think about the groups who were not independent. They were the Africans. They were the Indians. They were women. They were anyone who was not a white male. So the notion, the Enlightenment project, which had this hubris that we could control everything, including the world, when we can’t even really control ourselves.

And if we were having this discussion in 1980, we’d say, “OK, let’s not do race. Let’s look at everyone as an individual. Why do we have all these categories?” Well, now if you ask the question, why do we have all those categories, the science will tell us: That’s the way the mind works. The mind actually works with categories. We simply cannot process the world, we simply would not exist as a species, without categories.

Ms. Tippett: And yet, this condition of each of us in isolation, which you associate with whiteness, which is this culture of domination, is not sustainable, and it’s not desirable.

Mr. powell: It is not.

Ms. Tippett: And we’re running into the limits of our ability to convince ourselves that it is desirable.

Mr. powell: No, there are so many expressions that help us see it. And sometimes people talk about “We need to do things to connect.” And on one hand, that’s right, but on the other hand, it understates what it is. We are connected. What we need to do is become aware of it, to live it, to express it.

So think about segregation. Segregation is a formal way of saying, “How do I deny my connection with you?” in the physical space. Think about the notion of whiteness. So whiteness in the United States, as it came, as it took form, believed that one drop of “black blood” — whatever that is — would destroy “whiteness.” Turns out, whatever that means, most white Americans actually do have black blood. The reason that most African Americans look like me or like Gary is because white blood and black blood’s been mixing up for a long time. And so I think that as we deny the other, we deny ourselves, because there is no other. We are connected.

How do we actually acknowledge that? How do we actually celebrate that? And I think one of the things we have to do is have a different sense of whiteness, because whiteness is the hard nut that wants to exclude, that wants to dominate, that wants — and I don’t mean people who are phenotypically light-skinned. I mean the practice of whiteness.

Ms. Tippett: This culture, yeah. I had this great privilege — actually, a few of us on our team, to go to the civil rights pilgrimage. So we were at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church — King’s church. There was a white journalist there, and he’d been one of the main journalists who covered the civil rights movement, I think for The New York Times, but anyway, one of the major papers. He told this story about sitting with Dr. King; and this man, though, this journalist, had gone back and looked at his own family, as part of his investigation of that, and found all of this slavery, slaveholding. And he had this realization that he shared with us. He had this moment, this aha moment after covering this movement as a journalist, that that movement was as much for the sake of his soul as it was for the sake of people of color.

And it’s worth saying that. To me, that’s one way of talking about your point that we have to talk about whiteness.

Mr. powell: Well you’re exactly right. I was teaching a class at the University of Minnesota, and I was talking about the taking of Native American land. And most of my students were white students, and one student objected; it’s like, “This is a such-and-such class. Why are we studying the history of Native Americans?” And I said, “We’re not. We’re studying the history of America. So, when we talk about the appropriation of Native American land, or when we talk about slavery, we’re not talking about the history of black people, we’re talking about the history of this country.”

And Toni Morrison made the observation; she said, we’ve had all of these studies on what the institution of slavery has done to mark the black identity. She said, it’s about time we look at what it’s done to mark the white identity. It’s America. That’s what slavery is about. It’s about America. And I don’t care if you came here last week or ten days ago, you can’t understand this country without understanding the institution of slavery. It was pivotal.

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, opening up the race narrative with esteemed thinker and legal scholar, john a. powell. We’re with a live audience at the On Being Studios on Loring Park in Minneapolis.

Ms. Tippett: There’s language that you’ve been using that I really appreciate, of belonging. As we try to move beyond the language that’s divided us and the behavior that’s divided us, tell me how you came to that and what that means for you and how you think that might be powerful.

Mr. powell: The human condition is one about belonging. We simply cannot thrive unless we are in relationship. I just gave a lecture on health, and if you’re isolated, the negative health condition is worse than smoking, obesity, high blood pressure — just being isolated. So we need to be in relationship with each other. And so, when you look at what groups are doing, whether they are disability groups or whether they are groups organized around race, they are really trying to make a claim of, “I belong. I’m a member.” So if you think about Black Lives Matter, it’s really just saying, “We belong.” How we define the other affects how we define ourselves. And so, when we define the other at an extreme, it means we have to cut off large parts of our self.

One other example, which — I just love this. “Love” it is the wrong word. But there was a headline in a newspaper several years ago, saying, “We’re entering a state where, for the first time in over 350 years, the world will be led by a non-Christian, non-white country.” And what it was saying is, we should be afraid. So the early debates around integrating schools — the white segregationists were, “We can’t have integrated schools, because black and white children might get to know each other and might marry each other and have babies.” The civil rights movement’s was, “This is not about marriage.”

The white segregationists were right. You bring people together, they will actually learn to love each other. Some of them will marry and have children. And so it will, actually, change the fabric of society. When people worry that having gays in our community will change what marriage really means, actually, they’re right. When people worry that having a lot of Latinos in the United States will change the United States, they are right. We’re constantly making each other. And so, we can’t hold onto a notion that “This is what America is. So, Latinos, don’t affect us.” So part of it is that, our fear; that we are holding onto something, and the other is going to change it. The other is going to change it, but we’re going to change the other. And if we do it right, we’re going to create a bigger “we,” a different “we.”

Ms. Tippett: And there’s no way we can approach that challenge as you just described it, which is a human challenge, with laws or policies or school reform alone. But — let’s just say it this way — it’s a way of us taking up the language of the beloved community, which was the language, which was the goal, of Dr. King and John Lewis and all those people. And you use that language too.

Mr. powell: That’s right. We’ve learned some things since then; one time, we talked about integration, and we equated integration with assimilation. Arthur Schlesinger talked about that in some of his work. That was clearly wrong. We’re not going to all melt into each other. And yet, we do have to have a beloved community, not in a small sense, but in the large sense. And I would even extend it beyond people: to have a beloved relationship with the planet.

And to live that, and to have structures that reflect that, is a very different way of ordering society. And then, I think, we can also learn to relax. Then we don’t have to be afraid of the force. Yes, it will take us beyond what we’re comfortable with; who we are right now. But I think we need help in getting there. And right now we don’t have the language for that, because we still have the language of the Enlightenment project. We still have the language of, “You can be anything you want to be. You can control. You’re in charge of your own destiny.” Even the notion of sovereignty is very problematic; whether it’s a community or a nation, there’s no such thing as sovereignty. We are in relationship with each other. It can be a bad relationship or a good relationship, but we are in relationship with each other.

Ms. Tippett: OK, so I think what’s also relaxing about what you just said about belonging and reframing our relationship with the other is — one thing that becomes overpowering when we talk about race is, we tend to talk about clusters of issues, and whether it’s income inequality or schools or crime and incarceration, or segregated neighborhoods — and even on a global scale, it even gets into these issues of scarcity, scarcity of natural resources. So all of those things are problems. They are big issues. But when you start lumping them all together as what we have to tackle, it’s completely overwhelming and paralyzing. It’s not that the project of belonging is simple…

Mr. powell: No, it’s not.

Ms. Tippett: …but somehow, I feel that it might open our imaginations in a new way, which also might open possibilities for action.

Mr. powell: Well, I think that’s right. One reason the problems seem overwhelming is because we’re using the wrong tools to understand them and fix them. We’re actually talking about a profound change in paradigm. And so right now we’re still thinking about — it’s like trying to think about computers as fancy typewriters. So if you’re using the framework of typewriters to try to make sense of computers, it’s very clumsy. It doesn’t work. You have to really shift it altogether.

Or you think about automobiles. Automobiles were initially thought of as a…

Ms. Tippett: Horseless carriage. [laughs]

Mr. powell: …horseless carriage, right? So the whole way of understanding cars was like a carriage. So the metaphors break down, and they don’t work. And so right now we’re trying to use, I would say, the language of individuality, the language of the Enlightenment, to understand something that goes into a different area. And it makes it incredibly complicated.

Actually, I think that because everything is connected — I say this to my students sometimes. If you want to affect all of the people in San Francisco with the measles, it doesn’t mean you have to go around to each person, one at a time. Just go to BART, which is our subway, on a crowded day; expose it; it’s done. Because people are in relationship, they will do the rest of the work for you. So because we’re in systems, if we can figure out where are the — what’s called the “inflection point” in systems, it populates the whole system.

Ms. Tippett: So how can we make belonging infectious? Is that…

Mr. powell: How do we make it infectious; how do we — people are longing for this. People are looking for community. Right now, though, we don’t have confidence in love. You mentioned love earlier. We have much more confidence in anger and hate. We believe anger is powerful. We believe hate is powerful. And we believe love is wimpy. And so, if we’re engaged in the world, we believe it’s much better to organize around anger and hate.

And yet, we see two of the most powerful expressions — certainly Gandhi, certainly the Rev. Dr. King — and I always remind people, he was a reverend; he wasn’t just a “Dr.” King — even though he came out of a violent revolution, Nelson Mandela. He just — again, I met him personally — he just exuded love. And as you know, he had a chance to leave prison early. He refused to, unless it included structuring the country. He actually tried to actually lean into a notion of beloved community. He actually didn’t want the blacks to control or dominate the whites. He wanted to create — so his aspiration — and he’s loved. Even today, he’s loved in South Africa, and he’s loved around the world. So I think part of it is that we don’t have to imagine doing things one at a time.

And the other thing is that it’s not that we necessarily get there, but we claim life, our own and others. We actually celebrate and engage in life. And so, to me, it’s not “How do we get there?” It’s “How do we live?”

And there was a period of time when I was feeling really overwhelmed with a lot of this stuff. And I was talking to my dad, and I said, “Dad, this is just too much. I can’t do it all. I’m trying to do all of this stuff by myself.” And he looked at me; he said, “Well, john, you know you’re not alone.” And I said, “Well, what do you mean, Dad?” He said, “Well, you got God with you.” And I realized, although I don’t organize around God in the way that he does, my mistake was, I thought I had to do it; that “I” was defining it, instead of “we.” So…

Ms. Tippett: …you were in that white mode.

Mr. powell: Exactly, exactly.

[laughter]

So I think we should both get out of that white mode and do it together. [laughs]

Ms. Tippett: So I’m looking in your work, and you’re giving these pointers, but — so here’s something you wrote: “If you look at 1950s attitudes towards integration versus today, the majority of whites today say they’d prefer to live in an integrated neighborhood and send their kids to integrated schools. What they mean by that is a different question, but also the world and demographics of the country are changing. And to live in a white enclave is not to live in the world. And I think it has” — I think you were — this is an interview — “it has a certain deadness to it. It has a certain spiritual corruption to it.”

And you said, “I think most people, white, black, Latino, and otherwise, would like to see something different. We just don’t know how to do it. And we’ve been so entrenched in the way things are. It’s hard to imagine the world being different.” You speak for me, you speak for so many people. This is what we’re up against. I feel like this is what we have to attack first — this inability to see differently.

You told one story about Oak Park, near Chicago. It was just really helpful to me. You said, when we tell stories about, “You integrate neighborhoods, and housing values go down,” and the way we always tell the story is, “Blacks moved in, African-American — people of color moved in.” And the way we could tell the story is, “Whites moved out.” But you talked about how — just this very practical measure that was taken so that the housing values didn’t change. Would you just tell that story? I feel like these little stories are really crucial, as well.

Mr. powell: And there are really a lot of them. They’re little, and they’re big. So Oak Park is in Chicago. Chicago’s one of the most segregated areas in the country. Cook County has the largest black population of any county in the United States, and a lot of studying of segregation takes place in Chicago. So here you have Oak Park, this precious little community. And there were liberal whites there. And blacks started moving in. And they were saying, “Look, we actually don’t mind blacks moving in, but we’re concerned that we’re going to lose the value of our home. That’s the only wealth we have. And if we don’t sell now, we’re going to lose.”

And it basically said: If that’s the real concern — not that blacks are moving in, that you’re going to lose the value of your home — what if we were to ensure that you would not lose the value of your home? We’ll literally create an insurance policy that we will compensate you if the value of your home goes down.

And they put that in place.

Ms. Tippett: And “we” was what? The local government?

Mr. powell: Yeah, and they haven’t had to pay one policy. Whites didn’t run to the suburbs — further out to the suburbs, and that’s a stable community. It’s been that way for 50 years. So part of it is — and this is sort of interesting on a number of levels, because you could say, those white people were just being racist. They were just using the insurance policy as an excuse. Maybe, maybe not. So are you willing to actually take them at their word? Are you willing to embrace them and engage them where they are? Because people do have anxieties, and they’re multiple.

But I want to give two other examples, very quickly. Think about Katrina. So these examples are all around us, and yet, we don’t tell stories about them. Katrina — the face of Katrina, when you remember it, it was blacks stuck on roofs as the water was rising. What’s not told is that Americans, all Americans, gave to those people. It was the largest civilian giving of one population to another in the history of the United States. So here you had white Americans, Latino Americans, Asian Americans, trying to reach out to what they saw as black Americans. They were actually saying — they were claiming: We have a shared humanity. And they actually did a poll asking people if they were willing to raise taxes to rebuild: 70 percent of Americans said, “Yes, we would tax ourselves to help those people.” The pundits and the politicians ignored it, and so that story simply didn’t get told.

The fastest-growing demographic in the United States is not Latinos. It’s actually interracial couples and interethnic couples. That’s people themselves, right now, not tomorrow, trying to imagine a different America; trying to say, “I can love anyone. I can be with anyone.” So I think, when we start looking for it, we see expressions all around it. Oftentimes, they’re not celebrated. They’re not talked about. There are no structures for them. So we have to embrace them and lift them up. But there’s reason to be hopeful.

Ms. Tippett: And talk about a movement that is going to change the DNA of race, right? Richard Rodriguez talks about the “browning” of America.

Mr. powell: Yes.

[music: “Nocturno” by Bajofondo Tango Club]

Ms. Tippett: You can listen again, and share this conversation with john powell, through our website, onbeing.org.

I’m Krista Tippett. On Being continues in a moment.

[music: “Fairy Dust” by Stefan Panczak & Rachel Wood]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, opening up the question of race into the question of belonging. john a. powell is a wise, redemptive thinker on the frontlines of racial longings. I spoke with him in 2015, before a live audience at the On Being Studios on Loring Park in Minneapolis.

Ms. Tippett: Let’s invite you into the conversation.

Audience Member 1: Thank you so much. My name is Leo Lopez. I’m here with my two daughters, 13 and 15. I think it’s a very worthwhile educational experience, so I pulled them out of school. With the framework, according to Richard Rodriguez, that the browning of America is inevitable, do you think, as a banker, that if, collectively, people of color — if we own a proportionate amount of the wealth of this country, will race relations be better? So if the demographers are right, and in 2050 we’ll be 49.9 percent of the population — is my dream, of course, because most likely will not come to pass that we own 49.9 percent of the wealth — would that make things better? And am I wrong in championing that idea amongst us that we have a responsibility to build equity in that sense?

Mr. powell: Well, I think we definitely have a responsibility to actually build equity. I put something I call “targeted universalism,” and where we want to get to is not simply what whites have. We actually need to state what is our goal. And then our way of getting there will vary, based on how we’re situated. And different groups are situated differently. So if we just say, “Let’s have our proportionate share of what whites have,” that’s an improvement over where we are now, but it’s not far enough.

But the other thing is that when we talk about this beloved community, from our perspective, we’re talking about what I call a “circle of human concern” — a circle of concern for all life, human life and, I would say, non-human life as well. And in that effort, it’s important to make sure that people of color are really valued and situated and have resources and political and other power that other groups have. But it’s also important to actually continue to be in relationship to whites. I think, ultimately, a healthy world really requires not just a restructuring of what people of color have, but a restructuring of white identity.

And that’s not a project that we’ve taken on, because the serious problem — in the 1960s, Bundy wrote about the “negro problem” at the Ford Foundation, but today, I would write about the white problem. We really need to come to terms with the white problem — not in a negative way, not in terms of white guilt, not in terms of beating up on whites, but really trying to help whites, because we are deeply related, give birth to a different identity.

Audience Member 2: Hi, Dr. powell. I work right across the street at Minneapolis Community and Technical College, and I know that we have a St. Paul Public Schools principal in the audience. And you talk a lot about interdependence. And I’m wondering, if you were the czar of U.S. public education, what questions would you ask us to ask ourselves?

Mr. powell: The first question I would ask you to ask yourself is, why do we have a czar?

[laughter]

I think, no one person — maybe with the exception of Einstein, but no one person is smarter than all of us. And so part of it’s, how do we come together and learn together? And it’s interesting, because I’m doing that around the country right now; I’m working probably six different school districts, including Oakland and Seattle and several others. And usually, they invite me in for some particular issue. They don’t usually invite me in to be the czar, [laughs] but they’re having a problem. And the problem is usually organized, frankly, around — the schools have growing diversity, and they have a, what I call “opportunity gap,” between the white students and the students of color.

The best school system, or one of the best school systems in the United States was the Wake County school system. That’s the Research Triangle, which has more Ph.D.’s than any other area of the country. It was actually quite interesting, because they took it to the voters, and they said, “Do you want to have this school system which is educationally and economically integrated?” And the voters said, “No.” So then they took it to the politicians, and they said, “This makes sense, which — the voters said no, but would you vote for it as a politician?” And the politicians said, “No.” And then the business community said, “Unless you do something about the school system in Wake County, we’re leaving.” It was actually the business community that pushed it through.

And that’s just one example. It’s just not that hard. But what we do is, we say we want change, “but not in my neighborhood.” “Go fix North Minneapolis, or go fix this place, but my school is fine.” And your school might be fine, academically, but in a country as diverse as ours, and that’s becoming more diverse, if you’re not learning in a diverse setting, you’re being miseducated. So these things are not simple. There are some things we can do, but as we lean into it, we’ll find that they’re more and more complicated. But they’re also fascinating. This is sort of an interesting world we live in.

Ms. Tippett: It’s so important that you name the problems, and then you talk about how fascinating this is. There’s something about us defining — going into these conversations and going into deliberations about what’s to be done, treating it as a problem and an issue and a burden, and it may be all of those things — but also, life-giving work and fascinating work…

Mr. powell: I think that’s right.

Ms. Tippett: …that will make us, each one of us, more whole.

Mr. powell: Well, part of the thing — as a country, we really don’t like talking about race. And part of this is because it’s a hard conversation, and oftentimes, we do it badly. And it’s like if you have a party, and you invite people to your party, and it’s a bad party; then you say, “I’m going to have another party next weekend.” And it’s like, “I’m sorry.”

[laughter]

Mr. powell: “I’m out of town.” But it’s like, “Come; let’s talk about white privilege and about…”

[laughter]

“I think I’m busy.”

[laughter]

Audience Member 3: Thank you, Dr. powell. I’m wondering if you can talk a little bit more about the dualism in our language and move toward a more unitive consciousness — what you were talking about throughout your entire interview. Thank you.

Mr. powell: Well, thank you for the question. I say to my students that when something is binary and dualistic, just interrogate it, because life is interesting, complicated, messy, and then sometimes, there are through-lines through it. And in terms of the self, I actually talk about the multiple selves; that we actually have multiple identities, and in a really healthy society, I believe we will claim our multiple identities on every level. Some places, my most salient identity will be that I’m a tall black man. Sometimes it’s going to be that I’m over 60. Sometimes it’s going to be that, somewhere along the way, I lost some hair. Or it might be that I’m a cancer survivor. Things, our identities, keep changing. And if we allow the space, they will change. It’s that adage; you may have heard it — “To be or not to be?” That’s the answer.

[laughter]

Audience Member 4: Hello, I’m Lawrence Waddell, and I have a question about the psychological part. I wondered if you could speak to things like stigma. For instance, Krista had on Desmond Tutu, and I remember this story he spoke about. He said, he was on an airplane, and he said it was his proudest moment. There were two black pilots. And then the plane had trouble in the air, and he’s thinking, “Hey, there are no white pilots up there.”

[laughter]

Mr. powell: “Who’s going to fly this?”

Audience Member 4: I thought it was completely courageous and honest to speak to how, let’s say, ubiquitous this issue is, of stigma and the psychological part of what we’re trying to get over. I don’t know of psychologists that deal with the trauma that has happened. I’m just wondering if you had any thoughts on it.

Mr. powell: Sure, there’s actually a lot on this. There’s the whole mind science. There is a website called Project Implicit, where you can actually go and take a test to see — what you’re describing are these unconscious processes. The unconscious, actually, is very fast and very big. And it actually makes associations based on frequency. So, if you show Pavlov’s dog, the ringing the bell and the salivating, the bell has nothing to do with food, right? But if you ring the bell and feed the dog, ring the bell, feed the dog — pretty soon, the dog will actually associate the bell and food. So, if you show the picture of a black man and crime, we’re like Pavlov’s dog. At an unconscious level, we will create a neural linkage between “crime” and “black.” The same, in terms of, if you don’t see — you never see a black pilot, you will have an association that “Well, blacks can’t fly.” And this is social; this gets lodged into our unconscious. And most of the time, we’re not aware of it.

We can measure this, though. We can measure it in terms of skin resistance, pupil dilation — and it actually slows us up. Sometimes, our conscious beliefs and our unconscious practices are in conflict. And it actually slows us down, creates anxiety, creates what they call “cognitive depletion.” So, part of the thing is just being aware of this. And it doesn’t make us bad; it makes us human. That’s what intelligence is. It’s making these associations. Once we find them, though, we can then start to make interventions to interrupt them. So, one female math teacher does not disrupt the stereotype that women can’t do math. We need a critical mass. We need a number. And we need to talk about it.

And again, on issues of race, we’ve learned, through the ideology of colorblindness, we’re not supposed to notice. We’re not supposed to say what Desmond Tutu said. So part of it is having the courage to just say — if Krista feels uncomfortable, sitting here with me, she can say, “I notice something.” Now, she’s not likely to say that. I’m sure she’s not uncomfortable. I think we’re really comfortable with each other. But if she were to say that, she’d likely get blasted. “She’s a racist. She’s this, she’s that.” But we all have these discomforts. So, part of it is to create space where we can actually unearth these discomforts and help each other get beyond them, but also to have these practices. The first pilot won’t disrupt the stereotype that pilots are white. You need a critical mass.

Ms. Tippett: I love this, the science of implicit bias, where — it’s worth all of us learning about, because it is liberating from blame or self-blame. So it takes it out of that realm, but it is knowledge that is a form of power. If we can acknowledge this and know it about ourselves, then we start to have some kind of control over it.

Mr. powell: That’s exactly right. The thing about implicit bias — and it’s a whole field. And it’s all really blowing up since the last 30 years.

Ms. Tippett: With the police, yeah. And also, there’s a lot going on now with police forces. It was already happening.

Mr. powell: We’re starting to train police forces. The city of Seattle has agreed to have all 10,000 employees trained on implicit bias. And it’s huge. It’s just very big. And it’s sort of unfortunate we call it bias, because it’s really — implicit means unconscious, or not fully conscious. And the reality is, everyone has that. That’s human nature. And what’s in our implicit biases are social. They’re not individual. So in a society where we treat blacks a certain way — and we’ve done this. We looked at 11 million words that most people use over their lifetime; how frequently do you use “black” with negative? And it’s very high; it’s like 40 to 50 percent of the time. So all the time, that’s what you’re hearing. That’s what you’re seeing; that’s what you’re hearing. This is the air that we breathe.

You breathe that until you’re an adult, you’re going to have those associations. Whites will have them. Blacks will have them. Latinos will have them. If you have negative associations in a society about women, men will have them, and women will have them. But they’re social. So we have negative associations in this society about Muslims. They don’t have those negative associations in Turkey. So those associations are social. So part of it means that we have to look at what those associations are and where they come from. And we can create some prophylactic thing, but ultimately, we need to change the environment itself.

Ms. Tippett: Right. We change the “we,” we change the “I.”

Mr. powell: That’s right.

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, opening up the race narrative with esteemed thinker and legal scholar, john a. powell. We’re with a live audience at the On Being Studios on Loring Park in Minneapolis.

Ms. Tippett: One more question?

Audience Member 5: Hi. My name is Jna Shelomith, and I work for Ramsey County. And Cornel West says, “Justice is what love looks like in public.” And I’m wondering, can public policy help in making confidence in love infectious?

Mr. powell: Well, I think public policy can help a lot. There’s some research to say that if you want to change people’s mind, you change behavior. And if you want to change behavior, you change institutions. That is a debate: which is first. But clearly, they infect and affect each other. So how do we actually think about policies and structures that reflect our deepest values, our way of connecting? Think of something like restorative justice in schools. Think about actually giving expression to our ability to love each other. Think about holding up people who are — there’s a group at Berkeley; we call it the Greater Good. So I think there are ways in which governments, and private industry, as well, can actually lean into this. There’s a whole thing about a “caring economy.” How do we actually learn to care for each other? We did this with AmeriCorps, we did a little bit with the Peace Corps. I think, in a healthy society, we would actually care for each other, not by just giving money, but by being in relationship with each other, by actually sharing each other’s suffering.

I’ll tell you a story. My dad is — like I said, he’ll be 95 this year. When my mom died — they had this wonderful relationship. It was really out of a storybook. So people would say, “Well, growing up, you know how when your mom and dad fight?” And I said, “Actually, I don’t.” This just wasn’t our experience. So, when my mom died, and my dad was — he was ready to be done. And so he got a serious disease; they thought it was cancer, and they said they needed to operate. And he said, “No.” He said, “You know, I’ve lived long enough. I’m ready to go.” And all the kids gathered around, and we said, “If you need to go, Dad, you can go. But we still need you.” He said, “You’re all grown.”

So I did some research on his tumor, and I went back to him and shared the research to him. And I said, “Dad, I just want you to know, if you want to go, that’s fine. But there’s a chance that tumor will explode in your body, cause excruciating pain, and not kill you.” And he said, “OK, OK. I’ll have the operation.”

[laughter]

And then I said, “So Dad, why do you think” — because he’s very Christian, I said, “What do you think God is keeping you here for?” And he said, “I guess my last lesson to teach the kids is, how to care for me.” So instead of seeing it as a burden, because he needs care, it’s like, “That’s my last gift to you, is to teach you how to care.” And it really is wonderful. So I think that in a healthy society, we not just have the words that we’re “related” — that we actually learn to care for each other, and we celebrate that. And I think policy can help that, like Good Samaritan laws. I think a lot of things, we can do. But I think it needs to be animated by a sense that we are connected, that we share each other, and yes, that we, in fact, love each other.

Ms. Tippett: I’m just going to say, honestly, I feel what is evident in john powell’s work and in this room is that the worst things that happen, also don’t define us. There’s more to our struggle with this that’s alive and potentially redemptive.

john, I think you’ve been answering this question the whole time, but I do want to ask you, just in closing — in the course of your life, your evolution as a human being, the multiplicity of yourself, how would you talk about how you think, at this point, about what it means to be human? How you would begin to describe that, and that may or may not include the word “race.”

Mr. powell: That’s a big question, so I’ll tell you a story. I went to Stanford. I was one of the co-founders of the Black Student Union at Stanford. And we had a meeting, and in that meeting, we decided that there were definitely some good white people, but not that many.

[laughter]

And it took a lot of energy to find them. The transaction cost of finding good white people was way too high. So we decided, “OK, let’s just stop trying to find these — let’s not relate to white people.” Actually, I didn’t support that position, but that’s where the group went. And I left the meeting. It was about noon, and I was walking across Stanford. And I don’t know if you’ve actually been to Stanford, but the center part of Stanford is very busy, especially at noon, and there’s always people teeming about. And I’m walking back across campus in this area, and there’s nobody there. It’s empty. And all the time I was at Stanford, I’ve never seen that part of the campus like that. And then, there’s this one woman walking toward me.

Again, the physical space where students hang out is actually quite small, so you see students all the time. I’d never seen this woman before, and I never saw her again. And as she’s walking toward me, I notice she’s blind. And she has a cane. And she walks into a maze of bicycles. And I said, “Oh, that’s too bad.” And as she turns, knocks down bicycles, she starts panicking. And I’m thinking, “That’s really sad, but we just made this agreement. It’s not my problem.” I keep walking. She turns again, and she knocks down more bicycles. And finally, I can’t walk past her. And I go over, and I take her out of the maze of bicycles, and then she goes on her way. And I go back to the meeting, and I say, “I can’t do it. I can’t adhere to that agreement.”

And to me, that was one of the defining moments. And I sort of — I’m not a theist, but I wonder, how did the universe send that woman to me, that she helped me to engage and claim my humanity, that took me on a different path? And I think being human is about being in the right kind of relationships. I think being human is a process. It’s not something that we just are born with. We actually learn to celebrate our connection, learn to celebrate our love. And the thing about it — if you suffer, it does not imply love. But if you love, it does imply suffering. So part of the thing that I think what being human means — to love and to suffer; to suffer with, though, compassion, not to suffer against. So, to have a space big enough to suffer with, and if we can hold that space big enough, we also will have joy and fun, even as we suffer. And suffering will no longer divide us. And to me, that’s sort of the human journey.

Ms. Tippett: Thank you so much. Thank you all for coming.

[applause]

Mr. powell: Thank you.

Ms. Tippett: john a. powell is director of the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society and professor of Law, African-American, and Ethnic Studies at the University of California, Berkeley. He previously directed the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at Ohio State University and the Institute on Race and Poverty at the University of Minnesota. He is the author of Racing to Justice: Transforming our Concepts of Self and Other to Build an Inclusive Society.

[music: “Marazion” by The Echelon Effect]

Staff: On Being is Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mariah Helgeson, Maia Tarrell, Marie Sambilay, Erinn Farrell, Laurén Dørdal, Tony Liu, Bethany Iverson, Erin Colasacco, Kristin Lin, Profit Idowu, and Jeffrey Bissoy.

Ms. Tippett: Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice you hear, singing our final credits in each show, is hip-hop artist Lizzo.

On Being was created at American Public Media. Our funding partners include:

The George Family Foundation, in support of the Civil Conversations Project

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, working to create a future where universal spiritual values form the foundation of how we care for our common home.

Humanity United, advancing human dignity at home and around the world. Find out more at humanityunited.org, part of the Omidyar Group.

The Henry Luce Foundation, in support of Public Theology Reimagined.

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections