Joseph Califano

Religion and Politics

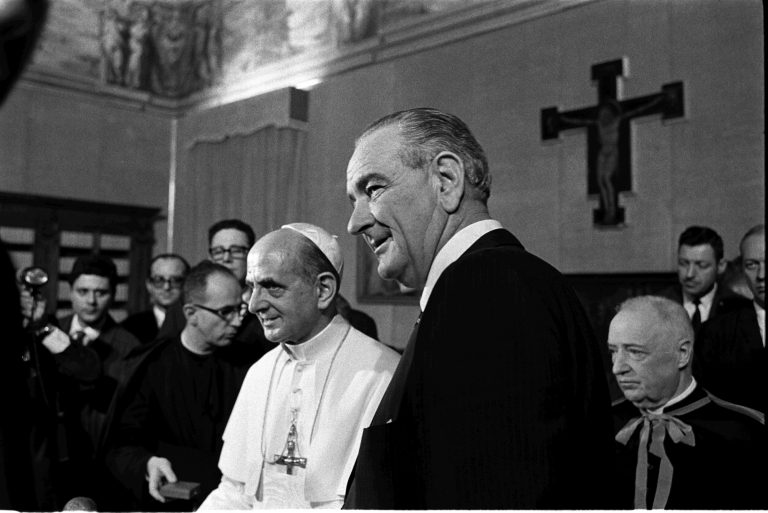

We speak with Washington insider Joseph Califano, a devout, lifelong Catholic, who held key positions inside the Kennedy, Johnson, and Carter administrations. Califano provides frank insight into the practical difficulties of applying religious ideals in the political arena.

Image by Yoichi Okamoto/LBJ Library, Public Domain Work.

Guest

Joseph Califano

is president of the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University. He was Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare from 1977 to 1979, and is the author of a memoir, Inside: A Public and Private Life.

Transcript

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: Krista Tippett, host: This is Speaking of Faith, conversation about belief, meaning, ethics and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett.

Today, as part of our continuing exploration of religion and politics, a conversation with veteran Washington insider Joseph Califano. Joseph Califano was born into a mixed Irish-Italian Catholic family in Brooklyn. He was raised with a devout faith in a pre-Vatican-II Church, defined, as he says, by rules of conduct as detailed as a tax code, but without the loopholes. And as Califano writes in his memoir, Inside: A Public and Private Life, his Catholic faith served as a moral compass by which he negotiated political life at its most Machiavellian. He was a young aide to Kennedy Cabinet members Robert McNamara and Cyrus Vance. In Lyndon Johnson’s White House, Califano spearheaded Johnson’s Great Society initiatives on poverty and civil rights. Later he was Jimmy Carter’s secretary of Health, Education and Welfare. Joseph Califano has experienced the tensions and conflicts of holding deep moral and religious convictions while in public service.

JOSEPH CALIFANO: I do think most presidents draw try and do what’s right, even when they do the most controversial things. Lyndon Johnson used to say, `You know, it’s not doing what’s right that’s difficult as president, it’s finding out what’s right that’s most difficult.’

MS. TIPPETT: Joseph Califano’s account of his years as a Democratic policymaker and Washington insider is called Inside: A Public and Private Life. His memoir offers a window onto the role of religion in both Democratic and Republican politics in our time. Califano’s political point of departure was the election of John F. Kennedy as the first Roman Catholic president in 1960. Today, Catholic presidential candidate John Kerry is under fire from some bishops for failing to follow Church teachings on abortion. But when John Kennedy was running for president four decades ago, he felt compelled to declare that Catholicism would not determine his policies. Here’s a segment from a pivotal campaign speech Kennedy gave in 1960. Former President John F. Kennedy: (From 1960 speech) I’m not the Catholic candidate for president. I am the Democratic Party’s candidate for president who happens also to be a Catholic. I do not speak for my Church on public matters, and the Church does not speak for me. Whatever issue may come before me as president, if I should be elected, on birth control, divorce, censorship, gambling, or any other subject, I will make my decision in accordance with what my conscience tells me to be in the national interest.

MS. TIPPETT: Senator John F. Kennedy, in a speech in 1960 in Texas that many believe secured him the presidency. In that year, my guest, Joseph Califano, was a young Catholic Harvard Law School graduate. Inspired by Kennedy, he changed his affiliation from Republican to Democrat and went to work in Washington, energized by the idea of public service. We talk a lot at the moment about religious speech by politicians. And my understanding had always been that, clearly, Kennedy’s Catholic identity was a huge part of the campaign and who he was. What I also understood, that he was always distancing himself, in a way, from the idea that his religion would limit him as the president, right? Or would define him.

MR. CALIFANO: Absolutely. It was a big issue.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. CALIFANO: And it gave him a major speech before protestant ministers down in Texas saying, `My faith will not control what I do as a president.’

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. CALIFANO: And Gustav Weigel, a great Jesuit theologian at the time, gave a major address that September of 1960 at Catholic University in which he said, `The Catholic Church will not try and dictate to a Roman Catholic president, and a Roman Catholic president is not bound by Catholic theology in making decisions of public policy.’

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. CALIFANO: It was quite different than today. And even then, eventually — I went to work for President Johnson in ’65, and President Johnson was the first American president to aggressively go after family planning. He believed family planning was an essential service for the government to provide the poor, he believed that we shouldn’t give foreign aid to countries like India unless they put in family planning programs. And eventually the Catholic bishops really rebuked him publicly on this. And he said to me, `Joe, I want you to go talk to them. We’ve got to work something out because we got to make peace with them. I’m not going to back down at all on what I’m doing, but we’ve got to make peace with them because before long the Catholic bishops may be the only people in this country that are with us on the poverty program and civil rights, which were two…

MS. TIPPETT: You know, that’s so interesting. Yeah.

MR. CALIFANO: …two very controversial programs. And I sat down with Father Frank Hurley. Frank Hurley was the lobbyist for the National Catholic Welfare Conference in Washington. And we sat down, and I, you know, he said, `The bishops are very disturbed.’ And I said, `Yes, but you know, you’ve got to remember, this is a president who’s doing all the things they believe in: He’s helping the old, he’s providing health care for them, he’s helping the poor, we’re having a revolution in — in civil rights for minorities, and what have you.’ And finally, Hurley and I worked out an accommodation, which was that the president would not use the term “birth control.”

MS. TIPPETT: Mm.

MR. CALIFANO: He would use the term “population problem,” which allowed for a solution that would include more for food, for example. And if he did that, the bishops would stop attacking him. And LBJ kept his part of the bargain, and the bishops kept theirs. He was no less aggressive in the policy he pursued.

MS. TIPPETT: Hm.

MR. CALIFANO: Now, you can contrast that with today in the United States. I doubt if you could make that kind of arrangement today…

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. CALIFANO: …in the current climate. Of — so, it was a, you know, incidentally, for me as a young Catholic — and you go back to the start of this broadcast — in those early years, it was a real lesson for me, because what I’d learned as a kid was, the only thing I — that I knew about bishops was, they came around once a year to your parish to give you Confirmation, give you a symbolic slap on the cheek as they Confirmed you to let you know that you ha — were going to be a soldier of Christ, and you might have to suffer for him. Well, now I realized that you could engage in a political negotiation with these guys and make it work.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, something that strikes me, but I think we don’t have much of a memory of now, is how incredibly idealistic morally, in a way, those years were — the ’60s and the Kennedy administration and the Johnson administration — when you’re talking about something like poverty, which you mentioned, or civil rights. And you know, you quote John Kennedy. It’s very striking for me the language that he used. He’s talking about civil rights. In fact, he’s talking about the moment when Governor George Wallace tried to block black students from the doorway of the University of Alabama. He said, “We are confronted primarily with a moral issue. It is as old as the scriptures and as clear as the American Constitution.” Pres. Kennedy: (From file footage) We are confronted primarily with a moral issue. It is as old as the scriptures and is as clear as the American Constitution. A part of the question is whether all Americans are to be afforded equal rights and equal opportunities, whether we are going to treat our fellow Americans as we want to be treated. If an American…

MS. TIPPETT: And that is such an interesting mix for me of political posturing and — very strong moral language, but — but on the other hand, quite different from the way we hear moral language today.

MR. CALIFANO: Well, it is. And let me give you an interesting thing about that.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. CALIFANO: That statement came out of a meeting in the White House at which there was a discussion among several of his advisors, then-Vice President Johnson and JFK of great concern about the politics of the whole civil rights movement because of the damage it was doing among white voters, including white Democrats. And in the course of that meeting there was a wonderful exchange in which one of Kennedy’s political advisors raised all these issues, and Lyndon Johnson said, `Wait a minute. This is a moral issue. This is not a political issue.’

MS. TIPPETT: Hm.

MR. CALIFANO: And there was silence for a minute in the meeting, and everyone kind of looked to Kennedy, and Kennedy said, `Lyndon’s right.’ And then, out of that came this. And when I worked for President Johnson, there was no question he regarded this as an overarching moral issue. And he knew the price we were paying. Indeed, this — no question but that you think about the two things of significance that he did in 1964 — major legislation in the wake of Kennedy’s assassination — and one was the civil rights bill in 1964, which opened up — ended — ended discrimination in public accommodations, ended discrimination in employment. Signing that Civil Rights Bill was a revolution. There were no more whites-only counters. There were no more whites-only fountains. There were no more whites-only hotels or theaters, and we had to end discrimination in employment. And the night Johnson signed that bill, he turned to an aide and he said, `We’re turning the South over to the Republicans for my generation and probably yours.’ Now he knew that.

MS. TIPPETT: Hm.

MR. CALIFANO: If you look at his statement signing that bill, and later — in 1965, his speech on the Voting Rights Act — they’re full — full — of moral references, that this was a funda — that went to a fundamental morality in terms of human dignity and individual rights. It’s the kind of rhetoric you don’t hear often. And years ago, Meg Greenfield was the editorial page editor of The Washington Post, and she just read that quote from Kennedy. She excerpted a significant portion of Lyndon Johnson’s 1965 speech urging Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act. And she did this, oh, I guess about in the 1980s, and she printed it as an op-ed. And the reporters at The Post said they didn’t know that presidents spoke that way.

MS. TIPPETT: Hm. It’s interesting, because these days we have more of an image of Johnson as a sort of Machiavellian figure, which he was, but this — this moral passion in him I think has gone lost a bit in memory.

MR. CALIFANO: I think it has gotten lost. I think it’s beginning to come back, and it even comes back a little bit in Caro’s third volume when he writes about the 1957 act. But I think he did, and as David McCullough said about Johnson, I mean, the first test of a great president is whether he’s willing to die for what he be — you know, forfeit his office for what he believes in, and LBJ certainly met that test on the civil rights issue alone. But the other thing was, the poverty, as you mentioned, the poverty program. First of all, it came out of a — of a book, Michael Harrington’s book on poverty, which was a very moral treatise. I mean, it was — it was seeped in morality and the immorality of having this kind of poverty in the wealthiest nation in the world. And the — the way Johnson talked about the poverty program, and the way Sargent Shriver did, and others, what — just, you know, if you pardon the expression, he just reeked of morality.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. CALIFANO: And the controversy was, you know, also tinged with optimism. You know, we can eliminate poverty. Let’s go to it.

MS. TIPPETT: Former Cabinet secretary and presidential aide Joseph Califano. As part of his domestic initiative, Lyndon Johnson pushed through the 1965 Voting Rights Act. The act lifted requirements some states enforced as prerequisites for voting, such as passing literacy tests, or paying certain taxes. These served primarily to limit the rights of poor, uneducated and African-American citizens. Here’s an excerpt from Johnson’s 1965 address to Congress encouraging passage of the Voting Rights Act.

PRESIDENT LYNDON B. JOHNSON: Our mission is at once the oldest and the most basic of this country: to right wrongs, to do justice, to serve man. The issue of equal rights for American negroes is such an issue. And should we defeat every enemy, and should we double our wealth and conquer the stars and still be unequal to this issue, then we will have failed as a people and as a nation. For, with a country as with a person, what is a man profited if he shall gain the whole and lose his own soul?

MS. TIPPETT: Democratic President Lyndon Johnson in 1965. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith, today exploring the complex relationship between morality, faith and politics through the memories of my guest, Joseph Califano. During three decades in public life, Califano was a controversial figure, a mix of idealism and aggression — something like the president he most closely served, Lyndon Johnson. Johnson’s time in office may be most vividly remembered for the nation’s conflicted will over American involvement in Vietnam. But Johnson was also the architect of what he called the Great Society initiative. Joseph Califano was his chief aide on this ambitious domestic agenda to abolish poverty, end segregation and improve education. Some programs from that agenda, such as Head Start, are still with us today. I asked Joseph Califano how he experienced the moral thrust of that political era as a Catholic.

MR. CALIFANO: Well, you know, everything we were doing was in line with everything the Jesuits had taught me, and everything I believed. We were full of social justice. It was health care for the old and the poor, with Medicare and Medicaid. It was education for the poor people with the Elementary and Secondary Education Act. We were eliminating discrimination with Voting Rights, with the Fair Housing Act. We were providing community health centers, and — and even with respect to the land. I mean, I really learned about the land from Lyndon Johnson more than anybody else. But when you — when you look at the Catholic writings and the morality theology on our obligation to take care of the land that we — we live on, that God’s given us to live on, the first environmental laws, the first clean air act, the first clean water act…

MS. TIPPETT: Hm.

MR. CALIFANO: …the first waste disposal act — all of this happening. And then the other piece, the little guy vs. the big guy. The people forget, and the country was changing dramatically, not just in terms of race — which was accelerated by Johnson and by Martin Luther King and the civil rights movement — but also the country was nationalizing. The local bank was going, the local grocer was going, the — the car dealer. So the individual — Johnson used to day, you know, `The individual’s faced with this enormous corporate behemoth, and that led to the truth in packaging laws that ha — have all the labeling we have today, and the truth in lending laws to try and, as he used to say, put the veteran and the guy buying a car on — on a par with these smart corporations. All of that, you know, we were constantly, as we saw it, in the domestic side, we were constantly on the — on the good side. We were constantly on the moral side. We were doing what was right. Now, incidentally, that didn’t mean that we always did it with halos over our heads.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. And you — you say that in your book.

MR. CALIFANO: There was a lot of hard ball.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. Say some more about that.

MR. CALIFANO: Well, I mean, I think it’s interesting, because you have to — I’ll give you an — an example. We were trying to pass a Transportation Department bill, and I was having very great difficulty getting it out of committee, which was chaired by a crusty Arkansas senator named John McClellan, and he just wouldn’t give. I was talking to the president about it, and what to do. And he said, `Let me tell you what to do.’ He said, `Go out there tomorrow and leak to the press that John McClellan won’t report out our Transportation Department bill because he’s got a lot of land he wants to sell to the Corps of Engineers, and — and make a lot of money on.’ I said, `My God! Is it true?’ And then he said, `You just let McClellan deny it.’ And what I realized had happened to me was, I was prepared to do it.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MR. CALIFANO: I was prepared to go out there the next day and leak the story about McClellan. As it turned out, we didn’t have to do because he cracked that following morning. But, you know, politics and passing bills is a tough business, and we often — you used the word Machiavellian, there’s no question Johnson was enormously Machiavellian in getting some of these bills passed. You moved a little bit from `Does the — the end never justify the means,’ to `Maybe there are some ends that justify a little grayness in the means.’ I mean, the black and white — the white with which the nuns wrote on that black board is not as clear when you’re actually dealing with these things day in and — and day out. For example, if Everett Dirksen, who was the Senate Minority Leader, wanted us to put an incompetent — I mean, an incompetent — in a particular job, if that’s what it required to get him to vote to kill a filibuster on a civil rights bill, we were prepared to do it.

MS. TIPPETT: I think this is a theme that runs all the way through your autobiography, your book Inside: A Public and Private Life. I mean, you — you were involved in some very controversial and complex and — and shady parts of the political ’60s, right? The Cuban Coordinating Committee, you know there’s a paragraph you start, “The first time in my government service that I was asked to lie came in April 1965.” You worked for Robert McNamara, also, before you went to the Johnson administration. And you talk about the compromise, that it’s always there in a political life.

MR. CALIFANO: Well, it is there. And I think it’s — you almost have to live it to understand it. Incidentally, on that occasion I did refuse to lie, but there are compromises all along the way. First of all, you never get all that you want, no matter how powerful you think you are. And then secondly, you’re constantly in this gray area where, you know, well, if you can get 90 percent of a loaf, is that OK? If you’re only going to help a certain portion of these people that need it, even though you know you’re going to have to leave another group without any help, do you do it? Well, we often decided to do it in those years. I think — but it’s difficult for people to understand is that the world is not full of black hats and white hats.

MS. TIPPETT: You and me, really. It’s not good vs. evil, or even good choices vs. bad choices, simply put. Mm-hmm.

MR. CALIFANO: It’s often the lesser of the evils; it’s often the closest to the good that you can get.

MS. TIPPETT: Veteran Washington policymaker Joseph Califano. He’s reflecting on a life in politics as a person of faith. Califano says that his ability to be in public service as a Catholic was most tested when he became Jimmy Carter’s secretary for Health, Education and Welfare in 1977. He was fired by Carter two years later, but during those years he was a key decision-maker on such issues as abortion, in vitro fertilization and euthanasia — medical and political developments that stood in tension with Catholic teaching, and which galvanized the Catholic public voice into the present.

MR. CALIFANO: The first test came — first of all, when it became clear I was going to be secretary of HEW, I’m a Catholic, first question in my mind as I thought Carter was going to ask me was could I enforce a law that federally funded abortion on a wide scale? And I actually sat down with a Jesuit priest, Father Jim English, who was my pastor at Holy Trinity in those days, and talked about it. And he said, `Look, you live in a pluralistic democracy, you fight for what you believe in, and then if you lose, you either enforce the law or resign, and you can enforce the law. One, because it’s a free country, and you’ve had a chance to have your say, and two, because you can always keep trying to change it. If you lived in a dictatorship, you couldn’t do that.’ Now, I went to work for President Carter. President Carter and I both opposed federal funding for abortion, Medicaid was funding about 300,000 abortions a year then. Roe v. Wade had just been decided.

MS. TIPPETT: This was 1976. You were secretary of Health, Education and Welfare under Carter.

MR. CALIFANO: And this is — actually this is late ’77, and Carter and I proposed that only funding of abortion be where the life of the mother was at stake if the fetus were carried to term. Congress passed a law that said they would fund abortions under Medicaid in cases of rape and incest as well. Then the question for me became, `OK, do I quit now? Do I stay in office?’ Then, `How do I interpret that law?’ Well, I have to interpret it the way I think Congress meant it. And in those days, women never reported rape or incest unless they thought they were pregnant. It was such a traumatic and embarrassing and horrendous experience. So I put out a regulation that said, `Prompt reporting would be interpreted as 60 days.’ The Catholic bishops exploded. They attacked me. Actually, President Carter was not happy, either. I said, `I did this because this is the realities of what Congress wanted.’ And Congress stayed with me.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hm.

MR. CALIFANO: I even had the bishops saying I should resign. I think that was wrong. I think if you did something like that, you wouldn’t have any Catholics in public life. And I faced a whole series of those issues. Sterilization.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MR. CALIFANO: The government had been promiscuous in sterilizations, and there was a terrible situation which a couple of young black girls were sterilized with federal funding, which I thought went beyond the law. And the bishops said, `You’ve got to ban all sterilizations.’ Well, that wasn’t what Congress intended, and I put out rules restricting them, not permitting them in cases of minors and not permitting them when people were under pressure, like pregnant women or people in prisons. And again the Catholic bishops attacked. I think you have to recognize that when you’re in public life you can fight for what you believe in, but you’re not representing the Catholic Church or any other church. And you’re not representing your personal views. Ultimately, when Congress acts and the law’s passed and you’re a public executive figure like a Cabinet officer…

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MR. CALIFANO: …your obligation at that point is to enforce the law or get out, and I wasn’t about to go to some Walden Pond or Vatican Hill. I wanted to be part of the public policy debate in this country.

MS. TIPPETT: And I belive that there is a tradition of that among Catholic politicians in particular in this country, right?

MR. CALIFANO: I think there is. I think we’re now seeing an incredible battle as the bishops — some at least — say they’re going to play the Eucharist card…

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. CALIFANO: …and deny Communion to Kerry or to others. And I think that fails to recognize the reality of what it’s like to be a public figure in a pluralistic democracy, and I think they have to understand. And where do you draw the line? If — you say, `Well, if they don’t vote against partial-birth abortion’ — which I am against — so Kerry didn’t vote against it, therefore Kerry should be denied Communion. Well, where do you draw the line? What about Rick Santorum, Republican, conservative, pro-life, anti-abortion senator who’s campaigning saved Arlen Specter in Pennsylvania, the Republican nomination, and guarantees him re-election? Arlen Specter is an aggressively pro-choice senator. Do you deny Santorum Communion? What about a Catholic governor who doesn’t exercise his leniency power to stop death penalties and — and…

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. CALIFANO: …commute them to life imprisonment? You should not draw the hard-and-fast lines. These issues are really issues that the Catholic Church has traditionally regarded as between an individual and God, as between an individual and his conscience.

MS. TIPPETT: Joseph Califano’s account of his years as a Washington policymaker and power broker is called Inside: A Public and Private Life. This is Speaking of Faith. After a short break, more from Califano on how the dynamic between politics and religion in Washington is changing in our time. Also, his frank reflection on the toll a public life can take on one’s deepest personal commitments. Visit our website at speakingoffaith.org to explore the ideas in today’s program and all of our past programs. We also hope you’ll sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter with a preview and my reflections on upcoming programs. That’s speakingoffaith.org. I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us.

[Announcements]

Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, conversation about belief, meaning, ethics and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Each week we explore how religious ideas shape human experience. Today, a new installment in our occasional series on religion and politics.

My guest, Joseph Califano, is a lifelong Catholic and a quintessential Democratic Washington insider. He’s written a memoir about the tensions and conflicts of holding deep moral and religious convictions while in public service. In key positions in the Kennedy, Johnson and Carter administrations, he was known for his high ideals and his ability to play political hardball. As an attorney, he represented the Democratic National Committee, and during Watergate, The Washington Post. Joseph Califano has described how he often had to balance his Catholic principles with his duties as a public servant. For example, Lyndon Johnson considered birth control essential to reducing poverty. Nevertheless, Califano helped that administration negotiate with Catholic bishops and win their support on anti-poverty initiatives. I asked Califano why, in his view, the atmosphere between the Catholic Church and politicians seemed so much more polarized today.

MR. CALIFANO: I think a couple of things have changed. One, if you go back to the ’60s, the bishops really backed off when John Kennedy ran. There was so much excitement about having a Catholic president that they just wanted to give him a full chance, and then everybody was excited when he was elected. Number two, these issues were not federal issues. More than anything, it’s the funding of health care and the genius of our scientists who wrestle with the will of God every day and produce these miracle procedures and identify the potential of fetal research and stem-cell research and everything else who make it so difficult to determine what the difference is between murder, suicide, euthanasia and natural death, because of all the ability to extend life. I think those things didn’t exist and didn’t involve federal funding and federal laws in those days. That’s important to remember. And then, you could talk to the bishops in those days, as we did. You could work something out with them. Now, today, I think the bishops themselves have become more aggressive in the public arena than they were. They also feel, I think, that they’re fighting for what they think are their bedrock principles. And I think we also have a terrific politicization of religion. It’s — it’s…

MS. TIPPETT: That the whole atmosphere is different in which the bishops are acting?

MR. CALIFANO: The atmosphere is entirely different. I mean, and we have this combination, if you will, of evangelical, protestants and conservative Catholics. You have Bush really pandering — is — is the — the word, if you’ll forgive me, that I’d use — to them and what they want. And you have another thing that’s happening here that we forget. There’s been a terrific politicization on the other side of the black churches.

MS. TIPPETT: Now, where does that plan into all of this?

MR. CALIFANO: Well, but I mean, I — I think that was — you know, look, in the poverty program, we had two allies in the inner cities and the rural South. They were the Catholic Church and the black Baptist churches. If we hadn’t had them, we could not, for example, have ever gotten Head Start off the ground. The original Head Start program — the — programs were largely funded through churches. But in the course of the civil rights movement, these black churches, which became the only power centers that blacks had in this country, also became political institutions. So we’ve had a lot of politicization of religion on both sides. And I happen to think until this current administration, we never had anybody so overtly go after these issues as religious issues, and so overtly bring religion into the political arena. And I think we’re going to see it all through this campaign.

MS. TIPPETT: Now, you know what? I’m going to push that because I have to say, one thing that’s very striking for me in reading the memoir is how much moral and religious fervor there was in something like the civil rights movement, and in Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society campaign. What’s the difference? How would you describe the difference, the nuances between that and — and what you — what you’re criticizing now?

MR. CALIFANO: Well, I — I think that the nuance would be the moral fervor was the moral fervor for social justice in the broadest sense, for all the people. That’s what drove the civil rights movement. That’s what drove the poverty program, a sense of social justice which had a moral underpinning. And they was nothing partisan about that. There was nothing saying that the Democrats had the high moral ground, or that we were the only people that have this moral standard. Today I think what’s happened is religion has become much more of a partisan instrument, and you have to look at it in that context. And there you have, in effect, Republicans saying, and the bishops implying — which I think will get them in a lot of trouble — `You can’t really vote for a Democrat, or a liberal Democrat, or a Democrat who supports the right of other people to have an abortion, and be a good Catholic. We never had anything like that in those days. Nobody said you were immoral if you didn’t vote with us on our poverty legislation. We’ve lost the recognition of good will on both sides of this thing. You know, we were adversaries in those days in a political sense, but we weren’t enemies. Johnson could have terrific battles with Gerry Ford, who was the minority leader in the House, on an issue, but they’d sit down on Sunday afternoon. I think there’s a very personal element here as well as this — and I also think — I don’t think we ever used religion as a political tool. I think religion is being used as a political tool today.

MS. TIPPETT: Hm. What would you be thinking of when you say that?

MR. CALIFANO: Well, I — I mean, I think. I just returned from Europe. There was a story in the Herald-Tribune that in his meeting in the Vatican President Bush asked the Church to help him because he was on their side on this whole array of right to life issues. It’s inconceivable that something like that would have happened in the 1960s, or even in the 1970s, you know? And — although, you know, Carter certainly was a religious…

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, I was going to say, Jimmy Carter was a religious person.

MR. CALIFANO: He was a religious president. It’s interesting to me, I mean, as I — as I note in the book, when I — when I first went there, I, a Brooklyn Catholic, was very uncomfortable when Burt Lance, who was his budget director and friend, before Cabinet meetings, down in the White House mess, we’d have this prayer breakfast in which we’d all hold hands and would pray. That’s not kind of the way you prayed a Brooklyn Catholic Church. But President Carter never brought that into any partisan setting, and I think that’s the big difference. It’s the partisanization, if you will, of religion, and it’s the sometimes direct sense and sometimes implication that you cannot be a good Catholic, or you cannot be a good protestant, or you cannot be a good Orthodox Jew if you vote for these guys. And I mentioned another thing I think is different today.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. CALIFANO: People poll today to identify who are practising Catholics, practising Jews, practising protestants and who are not, and devise appeals directly aimed at those groups. There’s a level of sophistication and targeting in polling and appeals that was unheard of 40 years ago.

MS. TIPPETT: Veteran Democratic policymaker Joseph Califano. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith. In his memoir, Califano offers rare insight into the difficulty of maintaining moral purity in a life in politics, however devout an individual’s faith might be. I’d like to come back to this idea, maybe take this a bit father, of — of the complexity of being a religious person and leading a public life, leading a political life. And you do bring that very much to the personal level in your memoir. You talk about how your work on great issues at the highest levels of government was very much in direct competition with your family life for much of your careers.

MR. CALIFANO: It — it was very — it was very difficult. It was like, certainly in the — in the McNamara/Johnson years, that first eight years, and even with Carter, I constantly felt as though I were torn between two goods — one good being my family, and one good being the work we were doing, laws we were passing, programs we were putting together for needy people. When I worked for McNamara, you know, he used to get in very early in the morning, like 6:30, and he’d work till 8:00 at night. I had two young boys, Mark and Joe, and after a few months, I — you know, I didn’t see them at all. And I went in to see Bob, and I said, `Mr. Secretary, I’m not seeing my sons. I’m willing to stay later or come in earlier, but I — I — one end of the day.’ And he said, `Fine you don’t have to come in until 8:00 in the morning.’ And…

MS. TIPPETT: But you still stayed until 8:00 at night, I assume.

MR. CALIFANO: Absolutely.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. CALIFANO: But with Johnson, it was all-consuming. He was a man-eater.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. CALIFANO: I was in there very early in the morning, and literally, most nights, not out of there until 10:00, worked all day Saturday, took my kids to Mass on Sunday morning, a quick lunch or Danish or something afterwards, and I’d work on Sunday afternoon. And when I look back over those almost four years with LBJ, I found out that all but, you know, maybe 10 or 11 days I worked. It was an incredible experience, and it takes a fearful toll. Took a fearful toll on my marriage, fearful toll on my wife.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MR. CALIFANO: I mean, basically I think she raised our — our boys. I mean, I did — I did everything I could to be there whenever possible, but…

MS. TIPPETT: And — and your first marriage did end, also.

MR. CALIFANO: My first marriage ended, and it ended in divorce.

MS. TIPPETT: What does that say about the challenge and the complexity of being a religious person in a — in a public life?

MR. CALIFANO: Oh, that — that’s a — that’s a tough question. I’ve thought often, would — would I have done it differently. I’m not sure it’s capable of doing it differently. I think that there ought to be more balance. I think we see many people today saying they’re getting out of public life because it’s all-consuming and they want to spend more time with their family. I think I was so full of adrenaline and on such an incredible fast track that I never had time to think about it. These things — you don’t sort of make a conscious choice. You get more and more involved, and you get more and more engaged, and then it’s not as though you’re doing something bad. You’re getting up every day…

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. CALIFANO: …and you’re doing something you really believe in, and you think you’re helping people, you think you’re taking your talents and using them in a way that would satisfy God. Meanwhile, you say, well, you’ve got a good wife, and she’s taking care of the kids, and thank God for that. And at the time you’re going through it, you don’t notice, it’s imperceptible, you’re growing further and further apart until suddenly you see there’s nothing there between you.

MS. TIPPETT: So what you are describing through this long career you’ve had a, as you say, a few times to — is that it’s — it’s gray. You know, you’re — you’re describing nuances of morality and differences in public and private morality and — and religious values that may — it may not be possible to — to live out, either in the — in one’s working life in government, or in the policies one is meant to enforce as a public servant. I mean, I want to know and, you know, and contrasting that with this — with this strong Catholic upbringing you had in Brooklyn, how — how does this life experience you had change your theology or your thoughts about what it means to be a Catholic, a religious person?

MR. CALIFANO: I think — I think being a Catholic is as important as anything in my life. I think it’s informed my life. I think the Church has grown. I think the Church is a much better place than the dot-every-I, cross-every-T religion that I lived as a six-to-20-year-old. It’s given me a sense that, you know, not only who I am, but whose I am, that I have these talents, I’ve got a measure of celebrity, I’ve got a great Rolodex. And what do I do with that? Well, I’m going to — God’s going to hold me accountable for that. `What have you done with that?’ And that’s a good measure who, you know, 12 years ago I stopped practicing law, where I was really making money for people that already had more than they needed, doing things that were really fungible — other lawyers could have done the same things — and started this National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University, because I saw this problem — drugs, alcohol, tobacco, pills. Substance abuse is involved in virtually every social ill we can look at — whether it’s something just like teen pregnancy, where most of the teens who get pregnant, one or both are high at the time — AIDS, crime, health care costs, child abuse, domestic violence, family breakups. Seventy percent of the kids in the child welfare system are there because of drug- and alcohol-abusing parents. The country still doesn’t seem to fully appreciate how important it is to deal with that. And I said, `All right, we’ll set up an organization. We’re going to try to figure out how to deal with it. And we’re also going to try to figure out how to get Americans to understand that they may have to do a lot of things to deal with poverty, but they’ll never deal with it unless they deal with substance abuse and addiction. And also a belief — I mean, I happen to believe, personally, very strongly that, while I think I’ve got the brightest people that have ever been put under one roof at CASA, which is what we call our center, to work on this problem, there are thousands of people out in America that, if they’ll only think about it, will come up with an even better idea. So that’s what I’m devoting my life to. I had — just as I was starting this, I got colon cancer, which was operated on — successfully, thank God — and then prostate cancer. And I — you know, you reach a point in life where you say, `Why does God spare me?’ Well he didn’t — he spares me to use my talents to do something, and this is the best use I think I can make of them, because nobody else was doing this.

MS. TIPPETT: Veteran Washington insider and Catholic layman Joseph Califano. He was 61 years old when he founded the Center for Alcohol and Substance Abuse in 1992. In what Califano titled “Final Reflections” in his memoir, he cites courage and tenacity as the most precious assets an individual can bring to public life. I asked whether he had the theology of qualities like these.

MR. CALIFANO: I don’t know if it comes from Catholic theology. I think courage comes from the — you know, there are lots of examples of courage in the Catholic Church. You know, St. Thomas More for the lawyers, all the saints, so many of whom they gave their lives for what they believed in. And I think tenacity, there are lots of examples of tenacity in the Catholic Church as well, both from among the saints and from among the works that the missionaries do. But I think, you know, where would we be in this country without courage? And the examples in the book are Katherine Graham, the publisher of The Washington Post, who put her entire fortune on the line in Watergate, as you mentioned earlier.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MR. CALIFANO: She would have lost everything if she was wrong about Watergate, or if they defeated her. I would have gone on to the next client. I was just the lawyer. She put everything on the line. Lyndon Johnson knew what he was doing. We got more vitriolic mail, and a greater, nastier mail on the race issue than we ever got on the war. The media was — kept publicizing the war, but the American people were really angry about what we were doing about race. I mean, I think those are incredibly important qualities, and I don’t know the extent to which I have them or don’t have them. I certainly intend to be tenacious about the issue of substance abuse as long as I’ve got the energy to continue this effort.

MS. TIPPETT: If I ask you if you have some models, in terms of this bringing together religious faith with public service, who comes to mind for you?

MR. CALIFANO: It’s hard for me to answer it in those terms. Let me try it in another term. I do think most presidents try and do what’s right, even when they do the most controversial things. I think George Bush, today, however we may disagree with him about the legitimacy of the war in Iraq, I think he believes that what he’s doing in Iraq is right. Lyndon Johnson used to say, you know, `It’s not doing what’s right that’s difficult as president it’s finding out what’s right that’s most difficult.’ I think it’s awfully hard to say religion moves somebody to do something. It’s not just the religion. As I — as I say in those — “Final Reflection,” I mean, it’s everything that happened to me in my life. It’s — it’s the streets of Brooklyn, it’s the Jesuit education, it’s the nuns, it’s Harvard Law School, it’s the White House, it’s the rough-and-tumble of practicing law in Washington. It’s all of those things.

MS. TIPPETT: All those things interacting with each other.

MR. CALIFANO: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MR. CALIFANO: I — and I think — I think they’ve all become part of the whole. You know, I wrote this book for my kids and my grandchildren, and I wrote it because I wanted them to understand, one, what an incredible country we live in — you can do anything in this country. You don’t have to know anybody. I didn’t know anybody when I went to Washington. My father was a secretary and an administrator at IBM, my mother was a public school teacher in Brooklyn. That’s number one. Number two, you cannot exercise public power responsibly unless you exercise it morally. You must have a moral compass. Mine was, by and large, my Catholic faith. Other people have other compasses, but you need a moral compass. And then thirdly, you do need courage. Courage is a — is a critical factor and — and very rare in public life.

MS. TIPPETT: Joseph Califano is president of the National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse at Columbia University. His book is Inside: A Public and Private Life.Joseph Califano provides a window on complexities we rarely discuss. Faith in public life. It’s complicated in many ways, not only when public figures commit flagrant acts of immorality. More often, perhaps, there are layers of compromise in the passage of every law. And there are compromises in any public life, as in any high-profile career, between personal and official commitment. A realistic view of politics also forces us beyond simplistic analyses of any era. Memoirs like Joseph Califano’s can provide a service if they make our scrutiny of the relationship between religion and politics more honest, and our assessment of our leaders more humane.

To delve into the ideas and backgrounds of this program, and all of our programs, please go to our website at speakingoffaith.org. While you’re there, you can sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter with a preview and my reflections on each week’s program. At speakingoffaith.org, you can also send us your thoughts and reflections on this program. We’d love to hear from you.

[Credits]

I’m Krista Tippett. Please join us again next week.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.