Khaled Abou El Fadl, Richard Mouw, and Yossi Klein Halevi

The Power of Fundamentalism

Religious fundamentalism has reshaped our view of world events. In this show, host Krista Tippett explores the appeal of fundamentalism in Islam, Christianity, and Judaism, as experienced from the inside. Three accomplished men, who were religious extremists at one time in their lives, provide revealing insight into the spiritual and cultural dimensions of fundamentalism. They also discuss religious impulses which counter the fundamentalist world view and helped them break free.

Image by Pierre-Yves Babelon/Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

Guests

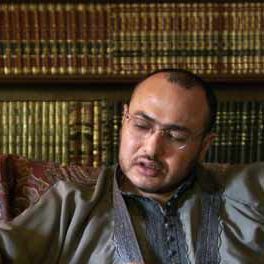

Khaled Abou El Fadl is Professor of Law at UCLA, and author of Tolerant Islam.

Yossi Klein Halevi is a correspondent for The New Republic, senior fellow of the Shalem Center in Jerusalem, and author of At the Entrance to the Garden of Eden: A Jew's Search for God with Muslims and Christians in the Holy Land.

Richard Mouw is president of Fuller Theological Seminary and a professor of Christian Philosophy and Ethics. He is the author of Uncommon Decency.

Transcript

August 19, 2004

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith, conversation about belief, meaning, ethics and ideas. Today, “The Power of Fundamentalism. “Violent religious fundamentalism is one of the great threats confronting the modern world.

Fundamentalism has a different history and expression in every religious tradition. The dictionary defines it as “a movement or attitude stressing strict adherence to a set of basic principles.” But that does not begin to describe the power of this way of seeing the world, nor its potential to motivate and to destroy. This hour we’ll hear why some people became fundamentalists, what drew them out of it and what we might learn from the fundamentalist impulse at this time. We’ll speak with three men. They are Muslim, Christian and Jewish — a lawyer, a seminary president and a journalist. Each of them has remained deeply religious while defining the foundations of their faith. When these men criticize fundamentalism, they’re not describing someone else. They’re speaking about themselves, their families of origin, their childhood friends.

KHALED ABOU EL FADL: It’s a form of intoxication and I grew out of it, but in the case of these kids and the — our kids, most of them never live long enough to outgrow it. Their lives are tragically short and tragically delusional.

MS. TIPPETT: When Khaled Abou El Fadl refers to `these kids,’ he’s also speaking of his own early years, a life he narrowly escaped. Today he is a leading international authority in Islamic law and human rights with degrees from Yale and Princeton. He’s a professor of law at UCLA, but he grew up in a middle-class family in Kuwait and Egypt, and he was a Muslim fundamentalist by the time he reached seventh grade. Khaled Abou El Fadl compares the kinds of young people who join Muslim fundamentalist groups across the world with the kinds of young people who join gangs in cities in this country.

DR. ABOU EL FADL: The main difference is that in the Islamic context, you’ve got to add a civilizational component. Normally, you know, a kid coming from a certain area of LA who decides to join a gang — he’s not thinking about changing the world. Even a Christian fundamentalist in the United States who joins a Christian group is not thinking in those terms. But those kids, they — they grow up with numerous mythologies about the greatness of the past and they look at their present, and the present is remarkably miserable at many different fronts.

MS. TIPPETT: Tell me how that was real and concrete for you.

DR. ABOU EL FADL: As an Egyptian, it becomes very concrete when you think everywhere you turn the — the identity to which you belong is confronted with military defeats. If you travel — you carry an Egyptian passport and you try to travel all around the world, you become thrown into a category of the inferior just by virtue of the fact that you belong to an Arab identity. And I remember, you know, going through a stage where I tried the — the sort of cool route of being Westernized. That, for me, didn’t work, and what did work was that — that exultation, intoxication, remarkable high of finding a group of people that tell you, `You know what? You’re better than the Americans. You’re better than the British. You’re better than the Arabs. You’re better than the church. You’re better than anyone because you’re Muslim and all you have to do is just simply accept our version of orthodoxy.’ And I remember, as a teenager, suddenly I would walk around with my head high. I belonged to something very powerful. And I could see the world as black and white, evil and good, and I was on the side — in fact, not just on the side of good – Anyone who wants to achieve goodness has to come through me. You know, they — they have to get my approval…

MS. TIPPETT: That’s the ultimate power, right.

DR. ABOU EL FADL: …so that was the high. That’s the intoxication. Fortunately, I grew out of it. Unfortunately, many of these kids never get that chance.

[music: “Jihad” by Soldiers of Allah]

MS. TIPPETT: A section of the song “Jihad” by the Muslim rappers Soldiers of Allah. Khaled Abou El Fadl is quick to note that there are versions of Islamic fundamentalism which are not violent. They may condemn the beliefs of others, but they leave judgment up to God. He uses the word `supremacist’ or `puritan’ to describe the militant Saudi Arabian Wahhabi brand of Islam to which he once adhered and which we now associate with al-Qaeda. Egyptian-born, Khaled Abou El Fadl is frequently called upon to analyze the theology of Islamic terrorism, and he cautions that social and political developments since the 1980s have left many young people in the Islamic world vulnerable to Wahhabi influence whether they and their families are extremist or not.

DR. ABOU EL FADL: In this theology, truth is unequivocally identifiable.

MS. TIPPETT: It is identifiable.

DR. ABOU EL FADL: It is identifiable. Not only is there a truth, but that this truth is attainable on this earth. Furthermore, the perfection of God is attainable on this earth. Third is that discussion, discourse, philosophy, history — all of that is either an aberration or sophistry. I learned very early on during this phase that philosophy is the science of the devil. The devil invented philosophy in order to lead peo — people astray. Intellectuals exist basically to confuse people. History, other than the his — other than the time period of the prophet and his companions, which is highly idealized — the rest of history is basically an aberration.

MS. TIPPETT: And — and so this identifiable truth is located, then, in a literal reading of the Qur’an?

DR. ABOU EL FADL: Well, that’s what you’re taught. I mean, that’s what you are taught. And of course, you know, most of these kids, the honest truth is they’re — they’re — they’re not very educated or even if they — if they are, their education is mostly in the sciences. When I started getting some education, everything that I was taught appeared to have been just a complete, remarkable fantasy and lie. I mean, one of the things I can tell you as — sort of as a matter of testimony is that the majority of kids who shared this view at that time had never read the Qur’an for themselves. And I remember that one of the teachers used to say that it’s a sin to read the Qur’an directly because the devil will play with your intellect. You have to read it through your teacher — i.e., him.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, that — that really helps me because in the bit that I know of the Qur’an and have read of the Qur’an, it strikes me that this is also true of the Christian Bible. You c — you can’t really take every line literally because there is a lot of contradictory teaching in there, or there’s a lot of nuance that — that — that has to condition your understanding of the text if you really are taking it seriously.

DR. ABOU EL FADL: Absolutely. And, in fact, one of the things that, you know, started giving me very serious doubts is that there is this sort of effect of — of eradication and destruction of your intellectual capacities. My father wou — told me back then, `Have you noticed that since you’ve gone on this thing that your — even your vocabulary has deteriorated.’ So I can’t open my mouth without throwing out some type of cliche that everyone in — in — in the mosque who attended these classes would be repeating.

MS. TIPPETT: In the West when we look at the root sources of terrorism, we tend to think first of poverty. And — and I have no idea from — from the life you’re describing what the economic situation was of you or the people around you, but I’m — I’m not sensing that you feel that that was as much a factor as the life of the mind and how that was oppressed.

DR. ABOU EL FADL: I absolutely would — would agree with that. I mean, I think poverty does play some role, but it is not in my own — at least in my experience in my own — my view, it was not the main thing. The main thing was the social turmoil and the lack of an intellectual life. Every day you read the — the newspapers, the — and the government-sponsored newspapers, and they all said the same thing. And, you know, the — you turn on the TV, the television, and it — there’s again, nothing there. There are no honest, straightforward discussions about anything. You know, basically it’s either how wonderful the government is, or it’s American movies that entice you with a life that you will — you can never have. So in that atmosphere, the feeling that I remember very distinctly is that I would just feel suffocated. Right before I started, you know, attending the — the classes of these guys, day in and day out I would wake up and go to bed, and always I would tell my mother and father, you know, `What’s the point? What’s the point of this life?’

[Excerpt from Ali Mullah]

MS. TIPPETT: Islamic scholar and law professor, Khaled Abou El Fadl. We’re talking about the power of religious fundamentalism. At the age of 15, with his father’s help, Khaled Abou El Fadl discovered Islamic jurisprudence, a body of Islamic thought that opened his heart and mind. This tradition with ancient roots debates how the Qur’an might apply to every aspect of life. It is something like the Jewish Talmud. Jurisprudence gave Khaled Abou El Fadl a life-changing alternative to fundamentalism, and he believes that it is the best hope for Islam today, a counterweight to the simplifications used by terrorists.

DR. ABOU EL FADL: The more I delved into the Islamic jurisprudence and how humble it was, how these medieval jurists, how remarkably humble they talk — they would never say, `God — God’s law is’; they would always say, `In my view, God’s law is — and God knows better.’

MS. TIPPETT: Right. I mean, humility is not a term that we would associate with some of these more terrifying images — Islamic images we’ve had in the last months.

DR. ABOU EL FADL: Far from it. To me there was a little bit of even a — I have to admit like a post-traumatic reaction as I watched bin Laden speak after 9/11.

MS. TIPPETT: In the videotape?

DR. ABOU EL FADL: Yeah, on Al-Jazeera channel. You know, I — I listened to it in Arabic, of course, and the — you know, the smugness, the arrogance, the — the — the complete obliviousness to the other and the suffering of the other and the pain of the other — at one point I had a physical reaction where I started feeling my body hurting because at the time that I had informed these — these guys that I was no longer going to attend their classes, I’m going to attend the class of the real jurists…

MS. TIPPETT: This is when you were a teen-ager in Egypt.

DR. ABOU EL FADL: Yeah, I think I was, like, 15 at the time. I was beaten, quite savagely, and you know, all the — the — the friendship of the past, you know, meant nothing overnight. And just watching bin Laden with his smugness and his arrogance put me back in that scary moment. But in my case, that beating — and there were several other after that — only sparked the — the defiance in me. I vowed and continued to vow never to — to shut up and to just stand up to this type of what I consider to be blasphemy against the Islamic tradition and the — what I consider to be a very beautiful and humanistic tradition.

MS. TIPPETT: There’s a Jewish writer and journalist, Yossi Klein Halevi, who’s written a book about a journey of worshiping with Christians and Muslims in the Holy Land, and he wrote Islam had a genius for fearlessness. The dark side was the suicide bombers, but he — he also saw a great strength. And — and — I mean, that’s also a quality that I hear coming through in — in your voice and in your story. I mean, what is the theological root of — of this fearlessness in Islam?

DR. ABOU EL FADL: Well, you’re — you’re — you’re sort of going to laugh. It’s actually — goes back to the theology of jihad. I mean, jihad means to struggle, right? I mean, it doesn’t mean holy war; it means to struggle and to stand for what you believe and to stand with friends and to trust that your reward at the end for doing what you do is with God. And what I am doing, I believe, is jihad. What — by writing my books and by lecturing and by speaking out — I believe is jihad, and I believe that if someone decides to kill me because of this, I believe I die as a martyr.

MS. TIPPETT: Khaled Abou El Fadl is professor of law at UCLA. His books include The Place of Tolerance in Islam.

This is Speaking of Faith. When you visit our website, you’ll find background on all the ideas mentioned in today’s show. You can also sign up for our weekly email newsletter, which includes transcript excerpts and my reflections on each week’s program. That’s speakingoffaith.org. After a short break, we’ll explore Protestant fundamentalism and Jewish extremism through the stories of Christian philosopher Richard Mouw and Israeli journalist Yossi Klein Halevi. I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us.

Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, conversation about belief, meaning, ethics and ideas.

I’m Krista Tippett. Each week we focus on a different theme, asking how human experience shapes religious ideas. Today, we’re exploring the danger and attraction of religious fundamentalism.

JERRY FALWELL: What we saw on Tuesday, as terrible as it is, could be miniscule, if, in fact — if, in fact, God continues to lift the curtain and allow the enemies of America to give us probably what we deserve.

MS. TIPPETT: These were the controversial remarks made on national television two days after the September 11th, 2001, terrorist attacks by the Reverend Jerry Falwell, pastor of a 22,000-member fundamentalist Baptist church, and one of America’s most outspoken conservative Christians.

REV. FALWELL: I really believe that the pagans and the abortionists and the feminists and the gays and the lesbians who are actively trying to make that an alternative lifestyle, the ACLU, People For the American Way — all of them who’ve tried to secularize America — I point the finger in their face and say, `You helped this happen.’

MS. TIPPETT: Jerry Falwell later apologized, but for some, like Richard Mouw, his remarks exposed the worst of modern Christian fundamentalism. Richard Mouw is the president of Fuller Theological Seminary, one of the world’s leading centers of evangelical scholarship. And he grew up in a fundamentalist home.

RICHARD MOUW: My dad had had a profound religious conversion one night when he was asked to perform. He was a hillbilly band musician, and he preached on street corners and he spoke in rescue missions, and he became a minister in a Dutch Reformed denomination, but he never really lost that initial fundamentalist way of viewing things. And by that, I mean he always had a kind of hostility toward anything that was associated with protestant liberalism. We were raised in a context where we were kind of anti-Catholic. We — we tended to think of the pope, if — if not as the Antichrist, as a good friend of the Antichrist.

MS. TIPPETT: Richard Mouw traces the origins of modern fundamentalism to the turn of the 20th century, when liberal protestant theologians began to embrace critical methods of studying the Bible. Most disturbing for some of the faithful, like his father, was a tendency to dismiss the supernatural power of God. And so they began to stress the importance of the fundamentals.

DR. MOUW: The fundamentals were generally acknowledged to be a list of this sort — that — it’s people who believe that the Bible is the authoritative word of God — they have — it’s a high view of Scripture, and so it’s the presupposition that you bring to the Bible as — as authoritative word from God. You believe that Jesus wasn’t just the great human teacher but that he was God incarnate, the son of God, that he was born of a virgin, that his death on the cross was a substitutionary atoning death, you know, that — that what happened on the cross somehow brought about — in some mysterious way it brought about our salvation in a way that nothing else could have done. And it’s the belief that he’s going to come again, that — that the world has not seen the last of Jesus. Fundamentalists also have an intense interest in Bible prophecy. I mean, the — the word `literal’ and `literalist’ are really misapplied to fundamentalists because they play around a lot with the symbols of the Scriptures…

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

DR. MOUW: …you know, the beasts of the book of Revelation. And they’ll ask the question, `Who does that stand for?’ And so they see that as a revelation in a kind of coded form that imparts genuine information about things that are going on in our own world.

MS. TIPPETT: So talk to me about the experiences, you know, the most vivid memories you have of growing up in that kind of context.

DR. MOUW: Well, for one thing, there was a vast network of — of institutions and organizations. There was, of course, the local church, but we had summer Bible conferences, we had youth organizations like Youth for Christ and Young Life, and later on, you know, InterVarsity Christian Fellowship and Campus Crusade. We had evangelistic crusades of the sort that, you know, Billy Graham made very famous. But there were a lot of evangelists that came through town. So it was a — being a fundamentalist was a very busy thing. You — you-you got to do a lot of things.

MS. TIPPETT: Why? I mean, is there a theological underpinning of that?

DR. MOUW: Well, because fundamentalists were very concerned about conversion and they — they — they were very open to creating organizations that targeted, that reached out to different groups of people who needed to be converted, and so they placed, like, a big emphasis on evangelizing young people, and you get these marvelously complex networks of organizations. And — and they had radio program — the seminary that I head up was started by Charles E. Fuller, radio evangelist in the 1930s and ’40s and ’50s who pioneered in religious broadcasting, one of the first international radio broadcasts. And every week he did his radio program and his wife was there, and she read the letters from people, and to this day I get people who come up to me, `I can still remember Mrs. Fuller reading the letters on — on the radio.’ And they had these gospel songs. They had wonderful choirs and quartets. In many ways, the fundamentalists who were very much against some of the more visible manifestations of popular culture — you’ve got to remember, these are people who did not go to the movies, they did not dance, they did not drink, smoke, they didn’t play pool, they didn’t play cards. They had all of this list of negatives. And they’re very well-known for things that they cannot do, and there you can find a lot of common ground with — oh, Hasidic Judaism and the more fundamentalist kind of Islam. But because they — they didn’t go the movies or they didn’t go to dances on Saturday night, they created their own rather vital forms of, as it were, religious entertainment. Mr. Charles E. Fuller: (From vintage radio programming) And now Mrs. Fuller’s going to read to you from some of the letters, if I can find her here in the studio. Where are you, honey? Here. Come on.

[Excerpt from vintage radio programming]

MRS. CHARLES E. FULLER: Right here. Right here.

MR. FULLER: Right here. All right. Come on.

MRS. FULLER: Oh, good evening, friends. Here is a good letter from San Francisco. `Mr. Fuller, I was talking to a young man who told me he found the Lord through hearing your message over the radio. While staying home to take care of his brothers and sisters, he would turn on the radio…

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith. We’re talking today about the power of fundamentalism in Islam, Christianity and Judaism. My guest, Richard Mouw, grew up in a fundamentalist home and is now a Christian philosopher. Richard Mouw began to question his fundamentalist upbringing when he became caught up in the political movements of the 1960s. He became a passionate advocate for civil rights, an opponent of the Vietnam War and an organizer in the radical left-wing SDS while a graduate student. In recent years, he’s doing a great deal of thinking and writing about what the fundamentalist impulse reveals of human nature and what it has contributed to American culture. And with some irony, he traces those insights directly back to his religious political activism of the 1960s.

DR. MOUW: It was a fascinating experience because I was firmly committed to the anti-war cause and also the civil rights movement, just to take, you know, two prominent movements of the ’60s. And yet one of the things that — that struck me sitting in those endless participatory democracy anti-war protest discussion groups was that the passion of many of the young radicals was not unlike the passion of fundamentalism. And in my experience, as I left fundamentalism — and I left it behind for, oh, the three reasons that I talk about a lot in my book — it was very anti-intellectual and I could not live with that as I began to study and became interested in the intellectual quest, the scholarly life. It was very other-worldly; fundamentalists were not very interested in doing anything about issues of social justice or peace or — or righteousness in the larger world. And the other was a kind of separatistic spirit, a willingness to refuse to cooperate with any other Christians even if — if you disagreed with them, even on some minor point of — of doctrine. But, you know, it’s very interesting. In the civil rights movement, hymns were very important to the spirit of that movement.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. “We Shall Overcome.”

DR. MOUW: That’s right. And for me in many of those situations, as I was struggling, for example, as a person in my — my 20s with whether or not I was going to answer the — the draft call and — and be enlisted in the armed forces and possibly go to Vietnam, and I believed, and I still believe, that it was an unjust war, and I could not go, even though I wasn’t a pacifist and I — it looked like maybe I was going to have to go to jail. And people in my family and in my larger fundamentalist evangelical network were very critical of me, and it was a very lonely time for me spiritually and — and religiously because I felt cut off from my — from my roots. But what was interesting was that in all of that civil rights and anti-war stuff, the — the — the things that sustained me were those hymns.

MS. TIPPETT: Even when you did not perceive yourself to be nearly as religious.

DR. MOUW: Yeah, in those revival meetings, those hymns actually had a very radical scope and a radical tone to them; you know, `I surrender all,’ and `Is your all on the altar of sacrifice laid?’ And yet it was — it was a very narrow radicalism. They concentrated on, you know, your sex life and maybe how you spent your money. But what struck me and — and many of my friends in the 1960s was — it was also an important question: Are you going to yield your racism to the lordship of Jesus Christ, you know? Are you willing to be obedient to the gospel even when it goes against what your government asks you to do? Those were very important questions, and it was really the radicalism of those hymns that went well beyond anything that I think the people who sang them — who taught them to me — anything that they intended. But — but I took the words — I — I saw myself as taking the words more seriously, in some cases, than — than they did.

[Excerpt from “We Shall Overcome”]

MS. TIPPETT: You name the passion, and the — the — the exhilaration of — of the — those — the civil rights movement and those political movements that you become involved in, and — and I also think when I read your work that there’s a real emotionalism to — you know, to a gospel tent meeting that you describe. Is that for you also a defining characteristic of fundamentalism?

DR. MOUW: Yeah. I — I have to say — and I was — I was with a group of sort of ex-fundamentalist types recently, and I think I made them a little nervous by saying this, but I said, you know, since those fundamentalist days I’ve explored a lot of different strands of Christian spirituality — you know, Benedictine and Franciscan and, you know, the desert fathers and the desert mothers and — and all these wonderful things, and I’ve learned so much. But in those moments, in those old revival meetings when the — the preacher would say, `Every head bowed and every eye closed and look into your heart and are — do you really love Jesus?’ For me those were some of the most sacred moments of my life. I don’t think I ever since then have experienced the transcendence that I experienced.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, we’ve talked in these months with regard to Islam, but also in a general way about the root — root sources of fundamentalism. And — and I think a positive question in there is what — what draws people — what is the — the human appeal of fundamentalist religious experience? And — and I wonder if you could say something about that from a Christian perspective.

DR. MOUW: You know, in our — in our so-called postmodern culture there’s — there’s a lot of confusion about questions of truth and value, morality, meaning, but there are a lot of folks who just care about how their kids are going to grow up. As I go out into the churches, for example, the — the more conservative, fundamentalist-type churches, I — I meet so many parents who — who have gotten into that just because they wanted someplace they could bring their kids where they would get something about a life that has meaning, that has solid values, that promises good things about the future. And fundamentalists — I want to say, at its best, fundamentalism gives people some things to rely on, some — some solid foundations. I don’t think we ought to dismiss that as a silly thing or some kind of inferior impulses. And for many people — and my own life is an example of this — it was a good place to begin. It just wasn’t a good place to end up. But I’ll always be grateful for people who, in my earliest days, told me that — that Jesus loved me, that there’s a God who’s in charge of history, that there’s a book that we can turn to to find answers to some of the most basic issues of life, and I’ve nuanced that. It’s gotten a lot more complex for me. But the fundamental way of viewing it is still what I hang on to for dear life.

[Excerpt from “Just As I Am”]

MS. TIPPETT: Richard Mouw is president of Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, California. His books include, “The Smell of Sawdust: What Evangelicals Can Learn From Their Fundamentalist Heritage.” I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith. We’re talking about “The Power of Fundamentalism” in three lives.

YOSSI KLEIN HALEVI: I grew up in a Holocaust survivor family in Brooklyn in the early ’60s.

MS. TIPPETT: Yossi Klein Halevi, an author and contributing editor to The New Republic, describes himself as a former Jewish extremist. He lives in Jerusalem.

MR. HALEVI: The Holocaust was the background and the foreground of our family life, which was very warm and loving but was also in some way an act of defiance. Against Hitler, we survived. My father was a survivor from Hungary who survived the war by living in a hole in the forest. That event — I would say that that hole was the prison through which I was raised to see the world — the notion of the Jews as a besieged, pursued, hated people, a people that could never find its place with the rest of humanity.

MS. TIPPETT: In his teens, Yossi Klein Halevi became involved in militant quasi-terrorist activities of the Jewish Defense League, and he was a leader in a movement called the Student Struggle for Soviet Jewry. In his late ’20s in 1982, Yossi Klein Halevi moved to Israel, which he describes as his spiritual home. Now he is Israeli correspondent for The New Republic, and a commentator on Israeli affairs for the Los Angeles Times. He is a committed Zionist, an observant Jew, and at the same time a spiritual seeker and a politically moderate Israeli. He spoke with me from his home in Jerusalem about what his life has taught him of religious fundamentalism’s power.

MR. HALEVI: To be a fundamentalist means to be wholly immersed — not holy, H — H-O-L-Y — but quite the opposite — wholly…

MS. TIPPETT: All right.

MR. HALEVI: …to be wholly immersed in your own theology, your own suffering, your own drama, your own historical and theological drama, to the absolute exclusion of any other drama. But the truth is, when I look back on it, it really allowed me to — to turn what otherwise could have been a — an emotionally crippling experience into a very vigorous youth. You are part of the chosen people, you’re part of — of an el — a spiritual elite. You are `it.’

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. HALEVI: And — and there is nothing more exhilarating than being `it.’

MS. TIPPETT: The word `intensity’ recurs…

MR. HALEVI: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: …a great deal in your memoir, and that word, I think, has a particular appeal for young people.

MR. HALEVI: You know, not long ago I — I went up to Nazareth into Galilee where a group of Muslim fundamentalists are camping out, trying to build a mosque that will overshadow the Basilica of the Annunciation, and really a typical fundamentalist move of trying to — to overshadow another faith by even just physically building a bigger religious structure.

MS. TIPPETT: And were they — they Palestinian?

MR. HALEVI: Yes, they were Palestinian, and I went up there and I spent some time with these young people, and I was struck by their pleasantness, and it really brought me back to my teen-age years — the self-confidence, the — the disdain, and among themselves the private jokes. Being in — in — in a fundamentalist world — it’s so funny. I mean, that — that’ll sound ludicrous to outsiders, but when you are with your friends, out away from the cameras, there is nothing funnier than sitting around with a group of fundamentalist insiders and laughing at the rest of the world. And so much of the fundamentalists’ humor is mocking all the jerks outside, and everyone outside your circle is a jerk — everyone.

MS. TIPPETT: Talk about that. Talk about how your perception of the humanity of those you are fighting — or perhaps you feel you’re defending yourself — but your — your opponents…

MR. HALEVI: Right.

MS. TIPPETT: …how your understanding of that i — is changed, distorted by fundamentalist thinking. Are they human beings?

MR. HALEVI: Look, right now I’m — I’m talking to you from — from a battle zone. I’m in Jerusalem. We hear ambulances regularly on the road just below where I live. I live at the — the very edge of Jerusalem, literally the last row of houses before the Judean desert and — and West Bank begins, so I’m — I’m sitting physically on the border, the precise point of the border. (Sound bite of bombing site aftermath)

MR. HALEVI: I feel the war impinging constantly, so that my relationship with Muslim fundamentalism is not neutral, it’s not — it’s very hard for me to feel that empathy which — which in better times I am able to draw on. But right now I feel that my — my children are on the front lines every time they step outside the door, every time they go on a bus. And my daughter — my 16-year-old daughter was telling me the other day that the first thing she does, she gets on a bus — she immediately sits in the back because she knows that suicide bombers tend to blow themselves up in the center of the bus to — to kill more people, and then she — she scans all the passengers to see who the likely candidates are, whether there’s — there’s anyone on the bus who might be a suicide bomber. And then when she looks around and she sees everyone looks OK, then she — she’ll put on her headphones and listen to her music.

MS. TIPPETT: Tell me what you understand, explain to me what’s going on in the mind of someone who thinks it’s righteous and virtuous to sit in the middle of a bus with a bomb.

MR. HALEVI: For the suicide bomber, the victims are abstract. They’re not even real people. They’re props in an apocalyptic drama in which he is the star. And all of history, all of humanity has been set up for his passion and for his justification, for him to reclaim what he believes is rightfully his — to right the wrongs that have been done to him, to his people, to his religion — so that this is an event that is not just sanctioned by God but has been set up by God as the culminating moment of human experience, the — the — the culminating moment of the purpose of God’s creation, which is to right the wrongs — the cosmic wrongs that have been done. It’s to banish evil. And that is what’s going through the mind of the fundamentalist terrorist, and that emotion I know very well because, although I personally was not involved directly in — in terrorist acts as a teen-ager, some of my closest friends were people who were planting bombs at Soviet embassies to try to pressure the Soviet Union at that time to free the Jews, to allow Jewish emigration. And I was intimately involved with those people and tangentially involved with that terrorist world. And the fantasies that I had of — of destroying the enemies of the Jews — they were — they were moments almost of — not almost; they were moments of religious ecstasy.

MS. TIPPETT: So I wonder if something that distinguishes, say, a positive religious moment from this kind of destructive religious moment is, in fact, the focus of the motivation?

MR. HALEVI: Right.

MS. TIPPETT: Something that became clear to me also in reading your work is this — this tightrope that a religious fundamentalist walks, that in focusing on evil there is the danger of becoming evil oneself; in — in living with a consciousness of enemies, one becomes an enemy.

MR. HALEVI: That’s a really good point that you’re making, and — and that is that when you put darkness, evil, injustice as the center point of your cosmology, then you risk being co-opted, drawn into — into that darkness. And I think that that was one of the moments for me of revelation of how my obsession with Jewish suffering, with the Holocaust, was — was distorting my — my life and my spiritual life.

MS. TIPPETT: Former Jewish extremist Yossi Klein Halevi. This is Speaking of Faith, and I’m Krista Tippett. Today we’re exploring the power of religious fundamentalism in our world today. After Yossi Klein Halevi turned away from fundamentalism in his 20s, he was deeply influenced by research on people who had suffered catastrophic traumas, like the Holocaust or the Soviet gulags. He learned that they survived and created meaningful lives afterward by reaching out to others and drawing on their own deepest spiritual foundations. Eventually he became profoundly curious about the other religions with which he shares life in Israel. In 2001, he published “At the Entrance to the Garden of Eden: A Jew’s Search for God with Christians and Muslims in the Holy Land.” Yossi Klein Halevi proposes that only when Jews and Palestinians understand themselves not as victims but as survivors can fundamentalism be defused. Still, I asked him how the survivor approaches the world so differently from the victim.

MR. HALEVI: I think the — the survivor understands that this is in its very nature a horrible world, a world of unbearable suffering, a world that I would say — a world where — where the soul really doesn’t belong. And what the survivor tries to — to learn from his or her experience is generosity rather than rage. Fundamentalists crave easy answers. The survivor understands that there are no easy answers in this world, and the more you get closer to how God must see this world, the more you’re able to take on paradoxes, contradictions, and that forces you into a mode of constant empathy where you force yourself to constantly look at how the world appears to others. And again, you know, in better moments, sitting here in — in Israel — in better moments I’ve been able to at least try to develop that sense of empathy toward the Palestinians, toward the — the Islamic world. It’s much easier when you don’t feel under constant attack.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. And — and what I’m so aware of in this journey that you describe with other faiths also is that you recovered precisely the thing that gets lost in the fundamentalist experience, which is the — the humanity. You know, you wrote about one Muslim Sufi sheik, “Suddenly the menacing mask had a benign face.”

MR. HALEVI: Hm. Right. Right. I — I think that the journey that I took into these two faiths was a conscious refutation of — of who I once was. The fundamentalist is ready, in theory at least, to give his or her life for — for their faith. And I felt that my transition from fundamentalist to pluralist wouldn’t be complete until I’d managed to draw on that fundamentalist vitality and in some way transmute it. And I decided I needed to not just engage Muslims and Christians in dialogue, but actually…

MS. TIPPETT: Right. That’s where we always go, isn’t it?

MR. HALEVI: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: We go to dialogue.

MR. HALEVI: You know — no, I — I — I felt in here, this is what I learned — this is what I learned from the fundamentalists. It’s not enough to talk. You have to live it. You have to fully immerse — you have to live your belief to its ultimate moment and enter all of your fears. And — and, believe me, there were moments when I was terrified, sitting in a mosque in a Gaza refugee camp, wearing a Jewish skullcap; and you really wonder, are you going to get out of the camp alive? (Excerpt from musical selection)

MR. HALEVI: What I learned in that very small and limited experiment was that when one approaches another faith with reverence and love, the resistance and the — all of the political and theological and psychological barriers that keep us apart, especially in this land, somehow get bypassed and you’re able to get through in a way that is — is — is impossible when the discourse is confined to — to discourse.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. And to political solutions, I suppose…

MR. HALEVI: That’s right.

MS. TIPPETT: …and political vocabulary.

MR. HALEVI: At this point, I don’t believe there is a political solution to this conflict. I — I think there’s so much accumulated rage and resentment and misunderstanding that I personally despair of a political breakthrough. I don’t believe that we’re — we’re anywhere near a spiritual breakthrough, either, although God doesn’t need millions of people in order to effect change. Where spiritual process differs, perhaps, from — from the political reality is that it doesn’t require masses of people in the same way that political change does. In fact, if you look at the history of religion, any religion, it’s the story of a few eccentrics, a few obsessives, who take it upon themselves to make their lives examples of that vision, which — which doesn’t yet exist, and allow themselves to become almost entry points through which the divine presence can interact with humanity and change humanity. So the way to resist fundamentalism is not through anger and hatred, because they’ll win. You cannot outhate a fundamentalist. The only way to — to win against fundamentalism is by drawing on those divine qualities that we as human beings are called upon by every faith at its best to emulate, and those are the qualities of an open heart, of empathy and peace.

MS. TIPPETT: Yossi Klein Halevi is a contributing editor of The New Republic and the author of At the Entrance to the Garden of Eden: A Jew’s Search for God with Christians and Muslims in the Holy Land. Earlier in this hour, you heard Fuller Seminary President Richard Mouw and UCLA law Professor Khaled Abou El Fadl.

For background on all the references in today’s program, and complete book and music lists, go to our website at speakingoffaith.org. There you can listen to this program gain and all of our previous programs. We’d also love to hear your reflections. You can write to us through our Web site, and also sign up through our weekly e-mail newsletter, where I offer previous and reflections on each week’s program, book recommendations and transcript excerpts. That’s speakingoffaith.org.

[Credits]

I’m Krista Tippett. Please join us again next week.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.