Kimberley Wilson

Whole Body Mental Health

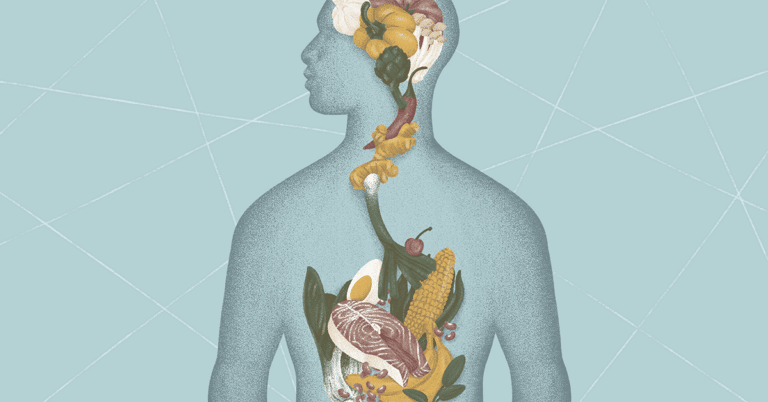

The British psychologist Kimberley Wilson works in the emergent field of whole body mental health, one of the most astonishing frontiers we are on as a species. Discoveries about the gut microbiome, for example, and the gut-brain axis; the fascinating vagus nerve and the power of the neurotransmitters we hear about in piecemeal ways in discussions around mental health. The phrase “mental health” itself makes less and less sense in light of the wild interactivity we can now see between what we’ve falsely compartmentalized as physical, emotional, mental, even spiritual. And so much of what we’re seeing brings us back to intelligence that has always been in the very words we use — “gut instinct,” for instance. It brings us back to something your grandmother was right about, for reasons she would never have imagined: you are what you eat. There is so much actionable knowledge in the tour of the ecosystem of our bodies that Kimberley Wilson takes us on this hour. This is science that invites us to nourish the brains we need, young and old, to live in this world.

Image by Cha Pornea, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Kimberley Wilson has a private psychotherapy and nutrition practice in central London. She co-hosts the BBC Radio 4 podcast Made of Stronger Stuff and is the author of How to Build a Healthy Brain. She came to the attention of many as a finalist in an early season of The Great British Bake Off. She grew up, as she tells it, eating both the West Indian food of her family and over-processed modern British fare.

Transcript

Transcription by Heather Wang

Krista Tippett, host: The psychologist Kimberley Wilson works in whole body mental health, one of the most astonishing frontiers we are on as a species — discoveries about the gut microbiome, for example, and the gut-brain axis, the fascinating vagus nerve, and the power of the neurotransmitters we hear about in piecemeal ways in discussions around mental health. The phrase “mental health” itself makes less and less sense, in light of the wild interactivity we can now see between what we’ve falsely compartmentalized as physical, emotional, mental, even spiritual. And so much of what we’re seeing brings us back to intelligence that has always been in the very words we use — “gut instinct,” as we say. It brings us back to something your grandmother was right about, for reasons she would never have imagined: you are what you eat. There is so much actionable knowledge in the tour of the ecosystem of our bodies that Kimberley Wilson takes us on, this hour. This is science that invites us to nourish the brains we need, young and old, to live in this world.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Kimberley Wilson runs a psychotherapy and nutrition practice in Central London. She’s published a book, How to Build a Healthy Brain, and she co-hosts an innovative podcast on BBC Radio 4, called Made of Stronger Stuff. That’s where I discovered her. She came to the attention of many as a finalist in an early season of The Great British Bake Off. She grew up, as she tells it, eating both the West Indian food of her family and over-processed, modern British fare.

Something that I’m always interested in, whoever I’m speaking with, whatever the subject, is tracing — asking how you would trace the roots of the questions that drive you or the passions that drive you, in your earliest life, in the background of your childhood. There’s a very arresting, I believe this is the first sentence of your book, which is so helpful: “I grew up with an intimate knowledge of mental illness and neurodegenerative disease; multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, schizophrenia, motor neurone disease, Guillain-Barré syndrome, borderline personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder … and depression all run in my immediate family.”

Taking a big breath.

So — I mean, I’ve also seen you say that you knew you wanted to be a psychologist, when you were 16, which makes sense to me, with that sentence in mind.

Kimberley Wilson: There’s a way in which I feel like none of us really owns, entirely, our trajectories. You know, there’s no such thing as a self-made person. And if I had grown up in a family of musicians, I’m sure that I would be a concert pianist. Or if I’d grown up in a family of artists, I’m sure that it would’ve had an impact on my relationship to art, and I’d visit galleries more often, or something like that. But I grew up with this intimate awareness of brains that don’t work, I guess, or brains that aren’t working well, so that when I got into school and we were doing biology lessons, I understood things like myelination and neurodegeneration and motor neurons and this sort of stuff. And in a strange way, it gave me a bit of a leg up, in terms of understanding aspects of biology and aspects of psychology. So these were subjects that kind of made sense to me quite early on. That was the path that I was on.

Tippett: And became inquiry, right? Those questions lodged in you. And also, when you were in The Great British Bake Off, you shared that your mother, she was a really intuitive baker, and that baking with her, and baking for her when her MS made it hard for her to stand — I see this connection in your childhood, between food as healing — not strictly the way you study it now, but there it is. There’s that picture.

Wilson: I’m not sure I would use — I see what you mean; perhaps not healing. I would say “care” and — of life; that kind of function of food which is around living and needing to fulfill this very practical life need of nourishment and energy provision. And so yes, it was kind of — although, you know, there was a book in my house called Foods That Harm, Foods That Heal. I don’t know how much science there is behind that title now, but growing up, it was a combination of the practical — people need to be fed, and food needs to be put on the table — but also, of simple pleasures and that very quotidian joy and pleasure that comes from eating.

Tippett: So you have gone on to be in this ongoing investigation, and also, you have become kind of a public educator on the science behind all of this. And it’s new, and yet I know that — I mean, I’ve been hearing people talk about microbiome for a few years — it is very new. I was quite intrigued, when I was just looking around, there is actually a paragraph on — because anything new is contested, right? It’s suspect.

Wilson: Of course.

Tippett: And this is revolutionary to say, a few centuries after the Enlightenment, in which we have built Western societies idolizing the brain and the mind, to discover a new organ, which is called a “second brain.” But I found, on the National Center for Biotechnology Information of the NIS, here: “The past decade has seen a paradigm shift in our understanding of the brain-gut axis.” A “comprehensive model” is emerging that “integrates the central nervous, gastrointestinal, and immune systems with this newly discovered organ.” And then it talks about “remarkable potential” shown in studies for novel treatments, not only in gastrointestinal disorders, but “psychiatric and neurologic disorders, including Parkinson’s disease, autism … anxiety, … depression, among many others.”

You have been wrapping your mind around this, and also bringing it into your practice, I believe, into your writing. But it is a new word. I feel like we have to kind of put this lexicon out there as part of our collective inheritance. So how would you start to describe what is the microbiome?

Wilson: So yes, the microbiome is really the population of microorganisms. And we hear a lot about the bacteria, but there are also viruses and archaea and yeasts, the fungi, hanging out in there as well. So this population of diverse microorganisms that — so everything has a microbiome. So your skin has a microbiome, your mouth has a microbiome, all sorts of — all over the body has its own microbiome, but the microbiome we tend to be talking about in this type of conversation is the gut microbiome, so the microorganisms that populate the colon.

And they aren’t just kind of squatters; [laughs] they haven’t just moved in. They do earn their keep, and they earn their keep, really, in this quite beautiful, symbiotic relationship, which is they are able to digest and make good use of parts of our diets that we can’t digest. So, largely fiber and polyphenol compounds that we don’t have the enzymes to digest, they get down into the colon, and the microorganisms can ferment it. And their metabolites provide a whole range of beneficial compounds and activities for our bodies, including the production of vitamins, the synthesis of short-chain fatty acids, the synthesis of neurotransmitters that don’t necessarily cross into the brain but can communicate, we think, with the brain, helping to train our immune systems and keep our immune systems functioning well. All of this is the symbiotic relationship between the microorganisms in our guts, our diets, and our overall health and genetics.

Tippett: So when they talk about an organ, is the organ the gut microbiome, or are all the microbiome — [laughs] whatever the plural is of “microbiome” — is the microbiome on your skin and in your mouth also part of that organ in your gut? Or when we talk about the organ, are we really just talking about the gut?

Wilson: I think it probably depends on the context. But it really doesn’t, I think, perhaps make too much sense to think about the gut without thinking about the microbes that live there, because really, other than the job of the microbiome, what happens in the gut is largely absorption of water from fecal matter. It’s really about what the microbes are doing there in conjunction with the immune cells.

Tippett: That is the gut function. The microbiome is the gut function.

And then another — just to kind of lay all of this out — another core piece of vocabulary and reality that we need to know is what I’ve heard you describe as your “fave”: the vagus nerve. [laughs]

Wilson: [laughs] It is. Yes. So the vagus nerve, it’s technically the 10th cranial nerve, which means it’s a nerve that comes out of the brain, out of the skull. And it is this beautiful — I have an image of it in my book. It’s beautiful. “Wandering nerve,” and it’s called vagus from the Latin root of “vag-“ — vagabond, wandering, And it does wander. It wanders throughout your body. So it goes down the back of your throat, it loops up around the ears, crosses down behind the voice box, it connects into your heart, into your lungs, into your liver, into your stomach, into all of your major organs, before rounding out in the gut. So it’s this direct, physical relationship between the body and the brain, and I think the main — one of the most important things to understand is that most of the direction of information is going from the body, up. So it’s not simply that it’s about the brain telling the body what to do. The vagus nerve seems to be the main way in which the brain is getting an understanding of the internal conditions of the body, in order to interpret that and then to make a decision about a behavior. So it’s this constant taking into account of the information that’s happening inside the body, largely unconsciously, to make a decision about what you should do next.

And the reason that that’s so important, I think, is about understanding that relationship between that and our emotionality, because our emotionality is anchored in our bodies. And part of that is going to be about what your body is telling your brain about how the situational, the contextual information is being perceived and understood.

Tippett: And I’ve seen the map and it’s wonderful, and I’ve also heard you on your podcast on BBC Radio 4, Made of Stronger Stuff, just describe this route of the vagus nerve. What’s so interesting about it also, just to step back and think about — this is language that is new, it’s science that is new, but it’s knowledge that we’ve had, right? So if I would say to someone, “I was nervous,” “I felt nervous,” what are the components of that? As you say, it goes through the throat — my throat tightens up. Your voice gets strained. Your stomach feels queasy. I mean, we have experiences of those connections.

Wilson: We do. And it’s partly the way in which we have disembodied psychology or emotionality from the rest of the organism, which has landed us, I think, in I guess a lot of hot water; that it’s really undermined our ability, I think, first to understand what we’re feeling and how we’re feeling; but also, certainly thinking about therapeutically, it’s meant that for the last 400 years, since Descartes set up his dualism, we have been ignoring —

Tippett: I think, therefore I am.

Wilson: I think, therefore I am.

Tippett: I think that’s a soundbite of what Descartes meant, but yes, it’s the soundbite we’ve lived with. [laughs]

Wilson: And in an extraordinary way, because what we don’t really think about, about that statement, is that actually Descartes was setting out his case for the existence of the soul. But it was hugely influential on other spheres of existence and life and professional and academic life, including medicine and what later became psychiatry and psychology, so that we understood the mind to be separate from the brain. We disembodied the mind from the organ that underpins it. And we are, I think, we are only just coming out of that phase, and it’s partly the research around the microbiome, nutritional psychiatry, that is helping us to bring back together, to reunite, the mind, the brain, and the body.

Tippett: To reunite ourselves, our sense of ourselves. I mean, also, in terms of application or therapeutic implications, if we understand these connections we can also — I mean, and this is a lot of what you’re working on — then we can have some agency in regulating, in tending these dynamics.

Wilson: Absolutely. One of the big issues at the moment, one of the very, very big concerns in terms of things like rates of depression — so depression rates are going up and up and up, and prescription rates are going up and up and up — but recovery rates aren’t great. Most people who will have a diagnosis of depression, 50 percent will continue to have symptoms, and 30 percent, in some assessments, 30 percent of people with a diagnosis of depression have what’s termed treatment-resistant depression. So even though we’ve had these apparently effective medications and treatments, people aren’t getting better.

So we’ve had to kind of reassess our understanding of the causes of depression. And this brings us back to the dualism, because we certainly think that for some people, their depression is largely driven by immune activation, or inflammation. It’s this contribution of the body — it’s not just about the way that you think or about unprocessed trauma. I’m a psychologist; these things are important. But we have to bring the body into the conversation, because for some people, the major contributing factor of their depression isn’t simply going to be their experiences. It’s going to be about the underlying biological processes that are driving this difficulty for them. And that means we have to include the body in our understanding of what happens in psychology and psychiatry.

[music: “Lissa” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being, today with psychologist Kimberley Wilson.

[music: “Lissa” by Blue Dot Sessions]

All of this is giving a whole new meaning to this thing that many of us might have heard our grandmothers say: You are what you eat. You are what you eat. If we — this new knowledge, how this functions, then we understand the importance of how we fuel and nourish and feed the gut and our system, and so I hear you — you are working, again, to add to our lexicon in new fields — nutritional neuroscience, nutritional psychiatry.

I have all these places I want to go with you.

Sometimes when people write about you, have interviewed you or written about you in the UK, they will comment on the fact that you became known to many people there, and probably here, through The Great British Bake Off, being a finalist in that. And so here’s something a reporter wrote in the Times: “Thankfully, she sees no compromise between being a lover of cake and safeguarding your brain health,” [laughs] which I think is important, because I think sometimes, often, when we step into this — and now, of course, not necessarily with all of this context, but there is a new awareness that we have been eating badly and that we can take charge of this, and some of that brings its own kind of stress, and also, reductionism to our relationship to food.

Wilson: Yeah, and it’s really about, I think, disentangling the contributions of food, inc., I suppose — food manufacturing, food production, industrialization of food, and the drive for commercial profit in food — and individual intake. And I think a lot of the conversation around poor diets places the emphasis and the totality of the responsibility unfairly on the individual, when actually there’s a greater contribution made by government policy, institutional nutrition — so what we’re feeding people in schools, in hospitals, in prisons — and the role of advertising and those sorts of things, on food. And so it’s not simply that we’re sending people out into a fair playing field, because actually, the odds are stacked against people, in terms of choosing foods that are going to be nourishing and beneficial for them.

Tippett: And there are clear connections now, between diet and depression, correct?

Wilson: Yeah. It’s — so in terms of depression, what we have are a range of pieces of evidence in different parts of the scientific literature. So what the epidemiological evidence shows us is that the more you adhere — generally, the more you adhere to a healthy diet — and “healthy” is really, broadly, we can just say a whole food diet, so whole grains, nuts, seeds, fish, leaner meats, fruits and vegetables, that kind of thing; non-industrial, whole foods — the lower your risk or the more protection you have from later development of depression, even when you’re controlling for things like income, family status, the type of job you have, and so forth.

So it might be about the lack of fiber having an impact on immune function and inflammation. It could be about the role of depletion of nutrients, because the more processed a food becomes, the more depleted it becomes in nutrients like B vitamins, which are essential for brain health, like omega-3 fatty acids, which are essential structural properties of brain cell membranes and so forth. So we could be talking about the impact of nutritional deficiencies. We could be talking about the impact of blood sugar spikes on cortisol production and how that affects your brain and your mood.

So bringing this all together, yes, we have at least a compelling case for more research, but certainly for greater understanding of what’s happening, in relation to the role of food and nutrition in our brain and mood health.

Tippett: And in nutritional neuroscience and nutritional psychiatry — I mean, you are also are a practicing psychologist. I am also aware of professionals who are bringing this knowledge into how they work with patients. I mean, so that’s not a study, but are you also having this experience with actual people?

Wilson: Yeah. So the way that I work is to, as I say, whole body mental health. And so as well as doing a psychological assessment or a therapeutic assessment, as all psychologists will do, I will ask my patients for a sleep diary for five days, a five-day sleep diary, and I will ask them for at least a three-day food diary. And I have a degree in nutrition, and I have access to Nutritics, which is a nutritional assessment software, so I, personally, am able to have a look at how they’re eating. And if I suspect, then, that part of their eating is contributing to how they’re feeling, I have a dietician that I work quite closely with, who I’m able to refer them to, so they’re working with a network of people to support their mental health.

So it’s about, let’s see if we can understand what is contributing to how you feel. How much of it is the fact that you get four hours sleep per night, and can we address that? How much of it might be that you are surviving on chocolate cupcakes and coffee? How can we improve that? And then, how much of it is about the way that you think or the quality of your relationship or this thing in your past that you haven’t been able to face?

And that’s going to give us a much better opportunity to hit the right target. If we can understand what the causes are, then we have a much better opportunity to intervene in an effective way.

Tippett: This is just a specific question, but it was something that struck me when I looked at — you know, I think stress is also something that’s all around us and in us, and we live in a — these last few years and now, we live in an unimaginably stressful world. And that, too, is part of our experience of the world, often below the level of consciousness. One of the things that I found so interesting — I was reading you — I think this was from one of your blogs — is that the fight-or-flight — so we’re living in a state of uncertainty and very reasonable fear, about all kinds of things, right? And so that’s our fight-or-flight response; that’s the amygdala, actually, where — the vagus nerve goes through the amygdala, right? And one of the things you pointed out that’s just so interesting to me about food is that when we’re in that fight-or-flight mode, when our amygdala’s in charge, which I think for a lot of us is a lot of the time right now, it shuts down digestion; but also that the brain is a very hungry organism — and I think I’m saying this right — that the brain will actually take the nutrition it needs, to be fighting, which is not necessarily what we need to be grounded and healthy.

And I’m not sure that I’m paraphrasing that correctly.

Wilson: So your brain is an extraordinarily hungry organ, and it is — it really punches above its weight, in terms of the amount of calories it needs in relation to its proportion of body weight. So the very, very famous figure you will hear lots and lots of people say is, your brain is about 2 percent of your overall body weight, but it uses somewhere between 20 and 25 percent of your energy when your body is at rest. So of the roughly 2,000 calories per day that your body needs —

Tippett: That it’s our brain burning those calories, which is fascinating.

Wilson: A big chunk of it, yeah, the biggest proportion of that is your brain. And with that comes a huge nutrient demand. You need nutrients to make dopamine. You need nutrients — vitamin C, B12, phosphorus — to make serotonin. You need choline from eggs to make acetylcholine. So you need nutrients just for your brain to function well. You need fatty acids and choline to make the membranes and for your nerves to signal and talk, communicate with one another. So that’s your normal — if you assume that’s your normal distribution of nutrients.

But what happens when you’re stressed is that that is your body’s alarm signal. It is the emergency signal. It is “shut everything down and focus on survival” signal. And so what will happen is that your stress hormones also need nutrients. Your stress hormones are also composed of nutrients. And so your stress hormones get first dibs, first allocation, because it’s a survival system, on those nutrients, which is going to leave your brain and the rest of your body depleted. And this seems to be one of the reasons, or this is kind of one of the theories underlying why we see an improvement in stress management, with nutritional supplementation.

And again, this is quite useful information for a planet that’s been in crisis — I mean, I would say just for the last two years, but with the invasion of Ukraine, it’s incredibly stressful, certainly in Europe at the moment. This is important information, in terms of how we — the strategies that are available to us to manage our stress on an everyday basis.

Tippett: And kind of understanding this as a — that we’ve been a few gener- — I mean, really, since the ’50s, ’60s, we’ve been, in the West, and now we have taken our pathologies to the rest of the world — we haven’t been practicing whole body mental health. We haven’t been eating well. We’ve messed up our microbiomes. I mean, I’m curious, when you look at our world, also, which — again, there’s so many things to point at, but there’s also, just generally, this crisis of depression and anxiety, and very much so in the young. I’m the generation who grew up with parents born, you know, got married in the ’50s — the discovery of macaroni and cheese out of a box, [laughs] right? I mean, we didn’t actually — I think iceberg lettuce is the closest thing I got to anything actually green, from the ground. I ate a lot of Cheez Whiz. And we drank Coke or Dr. Pepper with every meal. Everyone I knew did this, in the middle of America. This is not how I eat now, but it strikes me as a way that we don’t bring this perspective and this knowledge into our public deliberation and investigation of how we’ve distorted our bodies, and that is being passed on generationally. And if we don’t bring that analysis in, then we also don’t address what can be addressed, fully.

Wilson: I guess we should start with saying that, of course, these aren’t the only — nutrition isn’t the only cause and cure of mental health concerns, and I think we need to be careful not to lay the responsibility fully with the individual.

But my concern now is that the very poor quality of the average diet is contributing to the kind of poor architecture or the greater structural vulnerability of brains in the first place. So in the UK, for example, the NHS, the National Health Service, recommends that everybody should eat two portions of fish per week, of which one should be fatty fish, so mackerel and herring and those sorts of things, but we know that the average adult in the UK is getting one portion of fish a month. And less than 5 percent of children are getting the recommended intake of fatty fish, and it’s very unlikely that they’re supplementing.

Tippett: And those are growing brains, right? Those are forming brains.

Wilson: Those are brand-new, rapidly developing brains that aren’t getting the structural components required for good brain architecture and resilience. And so when we’re looking at these increasing rates of depression, in developmental disorders in children, in externalizing behaviors, in mood and affect disorders, and we’re looking around and we’re wondering why children seem to be so unwell and increasingly unwell, and we lay the blame at social media — which certainly does need to take some of the blame — and the various stresses that come with modern life, we must, I think, be thinking about the structural foundations. If we’re thinking almost about buildings, how strong are the foundations? If the stresses are going to come anyway, how strong are the foundations? And the foundations of a healthy brain lie in a healthy diet.

[music: “Dire Ghost” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: After a short break, more with Kimberley Wilson.

[music: “Dire Ghost” by Blue Dot Sessions]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, I’m with the psychologist Kimberley Wilson, a practitioner on the emergent field of whole body mental health. She has been guiding us through fascinating frontiers of learning about the ecosystem that is the human body. She helps explain the underlying mechanisms and the mental health implications of advice that is suddenly out there, everywhere, about eating plant foods and fiber, fatty acids and fish. She’s been describing the gut-brain connection, the vagus nerve, and therapeutic connections now being drawn between depression and food — and why, in light of all of this, the language of “mental health” is itself too small.

I would like to ask you about a couple of components of our bodies, neurotransmitters, that are words everyone knows now, connected to mental health. And I also think that there are more expansive ways to understand these things that you can let us in on, and one of them is serotonin. I think this is one thing a lot of us — and I also have had serious clinical depression, and so I’m very grateful for antidepressant medication, which worked for me — but it’s not simple. And we keep learning what we don’t know.

Wilson: No, it’s not simple at all, and in fact, we’re not tremendously sure what serotonin does. So serotonin is a neurotransmitter, so a chemical messenger in the brain that is related to mood regulation. And the serotonin hypothesis was a rather straightforward hypothesis, which is that you need serotonin in your brain in order to feel good, and therefore, if you have more, you will feel better, and if you do not have enough, then you will feel worse. And so the most common antidepressant medications are SSRIs, so selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and they work by preventing, essentially, the recycling of serotonin. And so the theory is that it leaves more serotonin available for that second neuron, the receptor neuron, to pick up and to send on its message of feel-good-ness.

However, that doesn’t seem to be the way that it works in practice, and simply in the rate of treatment-resistant depression, so that we’re increasing the availability of serotonin in people’s brains and it doesn’t seem to be doing the trick, or at least, not for everybody.

Tippett: And you’ve also written about how serotonin, to be flourishing or doing what it does best, actually needs nutrient support.

Wilson: Yeah. So when people think about the role of nutrition in serotonin synthesis, they often think about tryptophan; and absolutely, tryptophan is essential. Tryptophan is an amino acid, so it’s a piece of a protein, and it gets converted into serotonin and then into melatonin. But in order to do that conversion, the brain requires other nutrients: vitamin C, phosphorus, I think B6, B9, in order to make that conversion. Iron, it needs. And so if you do not have those nutrients, then your synthesis is going to be impaired.

But the other thing — and I did a series of videos on my Instagram about this for people, about serotonin — is the biggest thing, probably, that you can do to improve the function of serotonin in your body is to manage your stress.

Tippett: And again, some of the things that you prescribe for, for example, minimizing stress or working with stress are things that are free: [laughs] fresh air, natural light, sleep, rituals, the quality of our relationships. You also talk about arguments for limiting exposure to the news, as a therapeutic intervention. And I have to say, I — or, probably, to social media; or, those two things are synonymous, these days. I have to say, one of the most fascinating podcasts I listened to that you did was on dopamine, another neurotransmitter that we — is a word that we toss around. I certainly associate dopamine with that dopamine hit one gets from getting a notification or going online, being on social media. It was absolutely terrifying and illuminating to hear you talk about the importance of dopamine, not as a high, but just as one of the things that helps us decide to get out of bed in the morning, that helps with our overall pleasure in life; and what you explained is that what disrupts dopamine, or what plays with dopamine, actually works to diminish the baseline of that basic energy we have for life.

Is that a correct way that I’ve said that? And that, to me, is the biggest argument I’ve heard for working with ourselves and our children, with these technologies. Forget about the fact that they’re buying us, they are messing with our baseline sense of well-being on a minute-to-minute basis.

Wilson: And really augmenting how pleasurable everyday life feels — how it feels just to be in your body, walking down the street; how it feels to be sitting and talking to your friends. In a way that I don’t think we fully understand — we haven’t had a full sense of the repercussions and the downstream effects, at all. But this constant opportunity to have validation — mmm, lovely piece of dopamine there — or a quick piece of entertainment, a funny joke, a sweet story — all of those, in a way, which is a kind of binge-like pattern, the question mark is: what does that do to our ability to sit and pay attention to someone in a conversation, our ability to focus on a piece of work that we need to get done, that doesn’t seem particularly interesting in the moment but is important for our long-term goals? I don’t think we have that information in, but it’s certainly something to be cautious about and to be wondering about.

And then there’s the kind of practical part, which is the — I think it’s called the “technoference,” which is that simply having access, or having your phone in sight, and particularly when you’re talking about something of emotional meaning and resonance, lowers the quality of your interaction. So if you are sitting with somebody and your phone is there, just looking at your phone, knowing that it’s there, lowers the quality of your connection with the person that’s in front of you.

That is …

Tippett: That is …

Wilson: … deeply worrying.

Tippett: Gravity.

Yeah, and I want to test something out on you, this feeling I have right now. I’m also, in my work, really interested in how what goes on inside us reflects outside us — reflects in our presence in the world, reflects on our life together. And I feel like you could look at so many things that are happening in the world that we have many ways to analyze and say that our individual nervous systems and our collective nervous system, that these things are in massive distress and that we are in a civilizational fight-flight-freeze moment. So I don’t know. I test that out on you.

Wilson: No, that’s a really interesting idea, and there’s a researcher called Capt. Joe Hibbeln, which is just a fantastic name, [laughs] to start with. But he has this anthropologic understanding, he takes an anthropologic look at the role of fish oils in the world. And so, for example, he says — the symbol for Christianity is the fish, right? And is it somehow this piece of collective unconscious, this understanding that there’s something about this food, which is associated with calm, which is associated with clear thinking, which is associated with peacefulness, that gets translated in this symbol?

And whether you think that’s valid or not, it’s a very interesting idea, because, bringing it back to the prison studies, this is what we see. You know, you improve people’s nutrition with vitamins and minerals and these fatty acids, and they become calmer. And they’re more able to think more clearly. And they have this distance between the antecedents and their behavior; they have a little moment where they can choose their response. And if there’s anything that is going to be conducive to solving of our collective problems, it’s the capacity to sit down, to manage our emotions, and engage with minds that are different from us.

But what that absolutely requires is that our brains are working well. In order to solve humanity’s problems, many as they are, what we need are well-functioning brains. And the big worry, for me and lots of people like me, who are looking at this research, is that the way that we’re living and the way that we’re eating is effectively and persistently undermining the quality of our brain architecture and, therefore, our ability to think and process and problem solve.

Tippett: Something else that occurs to me when I think about this — the connections, the connectivity, the interactivity that you’re seeing and sharing, the microbiome, the vagus nerve, the direction that that goes, often body to brain, and not just brain to body — I feel like the language that we’ve used, I think this language of wholeness, right — what do you say? Whole body mental health? — I feel like our descendants will look at a phrase like “mind-body-spirit” and think how quaint and primitive that was. Those were separate compartments, and you could be working with one of them and put the other one to one side. And that’s fascinating, right, that mind and body and spirit, emotions, conscience, behavior, consciousness — I don’t know if — there’s a trauma specialist named Resmaa Menakem, who’s worked a lot with racialized trauma in the body in really, really important and wonderful ways, and he calls the vagus nerve the “soul nerve.”

Wilson: Yeah, and I think this has been the real contribution of, again, another relatively young field of study, called psychoneuroimmunology, because one of the things that we understand — so if we’re thinking about depression, and if you look at the causes, the known risk factors of depression, it is parental illness or parental stress; it is poverty; it is adverse childhood experiences; it’s experiences of trauma, of accidents, of physical injury. So there’s this plethora of events and behaviors and actions and relationships that lead to an increased risk of depression.

But what seems to underlie all of these things is the stress system-modulated activation of the immune system, right? All of those factors switch on your stress hormones, your immune cells have receptors for your stress hormones, your immune cells get activated, and with chronic activation of your immune system, that can lead to — to get a bit technical — the loosening of the tight junctions in the blood-brain barrier, cytokines cross over, and you’ve got neuroinflammation and depression.

So all of these things come together. We cannot think of them separately from the body. If you’re saying the thing that’s causing you depression is the quality of your relationship, that’s not outside of you, it’s the way in which your body is permeable to the environment; that the environment is affecting you on a cellular level and that that is affecting your mood and how you feel and how you perceive the world, because the way you look at the world changes when your mood changes.

So yes, it’s going to be a kind of ridiculous hangover, a kind of antiquated way of thinking about the world, just to think of these things as separate. And I think the sooner we can start to think of them as integrated, and therefore to start treating them as integrated, the better off we will all be.

Tippett: Do you think that you kind of walk through — down the street or through your life differently, with this understanding that you have of your second brain, which is — your understanding of that is more developed than in most of us, or the fact that you are more microbial than human cells at any given time? Does that register in you in concrete ways?

Wilson: Sometimes. Yes and no. [laughs] So last week, I was furiously angry, [laughs] stomping around London at lunchtime over something that I knew, even at the time, even within the cloud of my rage, was just a minor inconvenience. And I was trying to work it out; I’d managed to hold onto enough of my thinking apparatus to be like, this seems like an outsized response to a minor inconvenience; what’s going on? And I realized it was simply that I was very hungry and that I needed to have some lunch. And then my cortisol dropped, and I felt better. So I still get caught out by this thing.

And I think that’s really important to understand, which is that we’re not rational. Humans love to think that we’re rational human beings. But our decisions, our feelings, our behaviors, our actions towards other people, might be affected by unconscious, qualitative information that’s coming through our bodies that we’re acting upon. So that’s always something to hold onto. So a very practical place to start is, what is happening in my body? How well slept am I? Am I hydrated? How have I been eating in the last couple of days? Can I attend to those things, and then see how I’m feeling?

[music: “A Burst of Light” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: Kimberley Wilson has a private psychotherapy and nutrition practice in Central London. She is co-host of the BBC Radio 4 podcast Made of Stronger Stuff. And she’s the author of How to Build a Healthy Brain.

[music: “A Burst of Light” by Blue Dot Sessions]

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Laurén Drommerhausen, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Jhaleh Akhavan, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Gautam Srikishan, April Adamson, Ashley Her, Matt Martinez, Amy Chatelaine, Cameron Mussar, and Kayla Edwards.

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent, nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org;

Kalliopeia Foundation, dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality, supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org;

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives;

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation, dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.