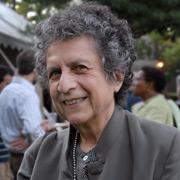

Leila Ahmed

Muslim Women and Other Misunderstandings

Is there such a thing as the Muslim world? Is the “veil” a sign of submission or courage? Is our Western concern about women in Islam really a concern for the well-being of women? Our guest, Egyptian-American Leila Ahmed, challenges current thought on these and other questions.

Image by Irfan Surijanto/Unsplash, Public Domain Dedication (CC0).

Guest

Leila Ahmed is Victor S. Thomas Professor of Divinity at Harvard Divinity School and author of several books, including Women and Gender in Islam: Historical Roots of a Modern Debate and A Border Passage.

Transcript

December 7, 2006

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett. My guest today is Leila Ahmed, an Egyptian-born Harvard scholar. Her personal history parallels some of the defining political and social currents of our time. She offers a lively, learned, and provocative challenge to current controversies about Muslim dress and to basic Western assumptions about Islam and the Muslim world and women.

MS. LEILA AHMED: You know, when people think about Muslim women, they think of the image of Saudi Arabia or Afghanistan. Why is that, when 90 percent of the Muslim world does not wear any of this stuff? And why is it that I never get called by a journalist — I get constantly called and asked to explain why Islam oppresses women; I have never yet been asked, ‘Why is it that Islam has produced seven women prime ministers or heads of state and Europe only two or three?’ or whatever it is.

MS. TIPPETT: This is Speaking of Faith. Stay with us.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett. Is Western concern about women and Islam really a concern for the well-being of women? Is the veil a symptom of their problems or of ours? My guest this hour, Leila Ahmed, provides essential historical background and challenges my thinking. From American Public Media, this is Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas. Today, “Muslim Women and Other Misunderstandings.”

In recent months, controversy has broken out across Western Europe over the religious dress and head coverings of Muslim women. France, for example, passed a law keeping religious symbols out of its schools, principally aimed at the Muslim headscarf. The Italian government, citing domestic terrorism laws, has prohibited face coverings. Some German states have banned public school teachers from wearing headscarves.

My guest, Leila Ahmed, is a professor at Harvard Divinity School and one of the most incisive contemporary scholars of women and gender in Islam. She’s also lived through some of the defining passages of recent religious and political history. She was born in Egypt in the waning days of the British Empire. The notion of the Arab world, and of Egyptians as part of that, had not yet been invented. But in our time, we refer to the Arab world as a fact of history and geography. We take it for granted and interchange it with another newly invented term, the Islamic world.

MS. AHMED: Yes. Well, look, for one thing, I no longer believe that there’s an Islamic world, because where exactly are the borders? Are they in Chicago? Where are they? Where does the Islamic world end and where does the West begin? Is it in Paris, or where is it? So I do think what happens in this country is going to be as much about the Islamic world as whatever happens over there. The Islamic world is no longer over there. That’s one thing. The other thing is, I think what we do, what we Americans do, will profoundly determine what becomes of what we’re calling Islamic world.

MS. TIPPETT: When it comes to analyzing Muslim women, Leila Ahmed says, Westerners need to question the most basic assumptions they hold. We tend to focus on Muslim clothing and headdress as a symbol of root problems. This has a long history, which she has traced. When Prime Minister Tony Blair recently called the Islamic full-face veil a “mark of separation,” he echoed a 19th-century British missionary who famously described Muslim women as “buried alive behind the veil.” Leila Ahmed has watched Western attitudes echo these patterns of the past ever since 9/11.

MS. AHMED: What we’re living through right now is so startling to me in some ways, partly because it seems to repeat history in a very disturbing way. And what I mean is it was extraordinary for me to turn on the television during the Afghan war and see women throwing off the veil, or see endless programs on CNN on the veil, see Laura Bush speaking about women in Afghanistan and liberating them. And what was disturbing there was to see the replay of what the British Empire did in Egypt 100 years ago. And it was almost hard to believe.

MS. TIPPETT: Tell that story.

MS. AHMED: Well, what I need to invoke here is the belief at the end of the 19th century that the veil symbolized the oppression of Muslim women. It’s part of the mythology of that era in which whatever was being done in another country, the countries that they dominated, whether it was India or sub-Saharan Africa or the Muslim countries, however the women dressed there it was the wrong thing. In sub-Saharan Africa, they didn’t wear enough clothes; they didn’t dress the way European Victorian women dressed. In the Middle East, they wore too many clothes. So the veil in the West in relation to Islam became the emblem of how uncivilized Islam was and, on the other hand, how civilized Europeans were. But the other twist that we need to remember at this moment in history, you know, Victorian dress was hardly the most liberated dress.

MS. TIPPETT: That’s right. And you point out that, even as Victorian women had thoughts of liberation and emancipation or, I don’t know, just progress, no one suggested that they had to discard Victorian dress for that of some other culture entirely.

MS. AHMED: That’s right. Exactly. And the wonderful example there, too, is that Lord Cromer, who was the governor of Egypt at the end of the 19th century, early 20th century, and he was the most vociferous advocate of how important it was that Muslim women unveil — and by the way, you can see a parallel, he was the Lord Bremer of that day, you know? I mean, not Lord Bremer.

MS. TIPPETT: Oh, Paul Bremer?

MS. AHMED: You know, Paul Bremer of his day. The Iraqi coalition forces or what…

MS. TIPPETT: Yes. He was in charge of our presence in Iraq after they actively entered…

MS. AHMED: Exactly. Exactly. He was conducting Iraq. So his equivalent figure 100 years ago was Lord Cromer in Egypt. But he was, you know, telling people how Egyptian society ought to be, and the first thing that had to be done was women had to throw off the veil because, until then, the men would not become civilized. He didn’t care about the women. Women had to throw off the veil so that Muslim men could become civilized, so they could raise civilized young boys who became civilized men. They would be like good British mothers.

Now, on the other hand, this same man, Lord Cromer, who was making such a big fuss about liberating Muslim women, in England he was the president and founder of the Society Opposed to Women’s Suffrage. He didn’t think women ought to have the vote. He thought Victorian society was perfect as it was, with a patriarch ruling over everything, and that is a society that ought to be spread across the world. And in the name of that, Muslim women had to unveil.

MS. TIPPETT: And, I mean, before that, before the 19th century, the veil had quite different connotations, didn’t it, than what it has today? I mean, it was something that upper-class women wore at that time?

MS. AHMED: That’s right. Now, I think we need to also distinguish what we mean by “veil,” because the head covering for women was the norm throughout the Muslim world, and actually head covering for men too was the norm.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

MS. AHMED: So that is often called the veil, and that’s what nowadays we see as called the veil. It’s a head covering, usually not a facial veil. And the face veil, in addition to the head covering, was worn by upper-class women. Everybody, though, wore a head veil. I mean, that was just normal dress.

MS. TIPPETT: Everybody meaning men and women.

MS. AHMED: Yes. Although, I mean, I can’t think of a man going bareheaded, but I don’t know if there was a law preventing them from going — I don’t think that was a law either for women.

MS. TIPPETT: I mean, you also tell — I had not read this — that the veil during Muhammad’s lifetime was used heavily in the Christian Middle East and Mediterranean.

MS. AHMED: That’s right. That’s right.

MS. TIPPETT: So this was actually something originally that Islam took from Christian culture, the Christian culture around it.

MS. AHMED: From Christian culture and from whatever other cultures were there. I mean, the veil was the norm in Iran, which wasn’t Christian, it was Zoroastrian. It was also a norm in the Christian Middle East. So it seems to have been a form of dress normal for particularly the upper classes of the region throughout, regardless of what religion they were. Jewish women too, Christian women, Zoroastrian women, that was just the norm of dress.

MS. TIPPETT: So obviously this original impulse against the veil was initiated by Westerners, as you say, people like Lord Cromer, also missionaries.

MS. AHMED: That’s right.

MS. TIPPETT: But it wasn’t necessarily about making women’s lives better.

MS. AHMED: I think the idea’s been politically manipulated, that’s what I mean. It’s used as a way of putting down Islam, supposedly because Islam oppresses women. You know, whenever you see the veil now prominently discussed in Western society, its implication is, ‘We are the superior civilization, Islam is an inferior civilization which deserves to be eradicated.’ That is all summed up in the symbolism of the veil. It’s not about women at all, I think.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, I mean, I don’t think it’s always so extreme, but there is a sense that, let’s say, women in this country would feel sorry for Islamic women based on seeing them in that kind of dress.

MS. AHMED: Yes, I think you’re right, that it’s not as deliberate and manipulative as it seems to be. I don’t know how to explain, but let me try to by saying, you know, when people think about Muslim women, they think of the image of Saudi Arabia or Afghanistan. Now, why…

MS. TIPPETT: They think of the burqas, don’t they? Yes.

MS. AHMED: That’s right. But why is that, when 90 percent of the Muslim world does not wear any of this stuff? I mean, why is it that I never get called by a journalist — I get constantly called and asked to explain why Islam oppresses women; I have never yet been called and asked, ‘Why is it that Islam has produced seven women prime ministers or heads of state and Europe only two or three?’ or whatever it is.

MS. TIPPETT: And America none.

MS. AHMED: That’s right. So what is it that is always focused on as the face of Islam and women? So I don’t think it’s really entirely innocent. I think it’s about political power and how we want to represent Islam.

MS. TIPPETT: Scholar and author Leila Ahmed of the Harvard Divinity School. She’s one of the first Muslim women on the faculty of a major American divinity school. She had a comfortable, sophisticated upbringing in Cairo and attended university at Cambridge. In the intellectual, professional, and governing classes of the Egypt of her childhood, she writes, there seemed no contradiction between pursuing independence from the European powers and deeply admiring their institutions. But in half a century, she’s seen that culture transformed.

MS. TIPPETT: Let’s talk about your experience. I mean, you grew up in Egypt. The women in your family didn’t wear the veil, did they?

MS. AHMED: No. Well, my grandmother wore a head veil.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. You live in this country now, you write about women’s issues, you know many American feminists. I wonder how you, as someone who grew up in that culture, not wearing the veil, thinks differently about those kinds of images than some of your American-born colleagues?

MS. AHMED: That’s a very interesting question because I too actually react against the veil. I grew up in a society where women did not veil. They were Muslims but they didn’t veil. And so the veil for me connotes a particular kind of Islam. I used to think of it — I no longer do — I used to think of it as a very dogmatic and fundamentalist type of Islam. So that is my associations. Unlike when Americans see a woman in a veil might think, ‘Well, this is just a Muslim custom,’ that never occurs to me. I know it’s not a Muslim custom, having lived it. I know that many — you know, many millions of Muslim women do not and have not worn it for, you know, 40 or 50 or 60 years.

MS. TIPPETT: What do you mean when you say that you used to think of that as a very dogmatic and fundamentalist expression of Islam but you don’t anymore?

MS. AHMED: Well, I’ll tell you, it was in my own lifetime, as a young person, the people who wore it were people who were affiliated with Muslim fundamentalist groups, or they were affiliated with groups whose origins were in Saudi Arabia and who were fundamentalists from where I stood. But nowadays, if you talk to young American women who wear hijab or veil or a headscarf of some kind, they’re not fundamentalists. Some of them are passionate feminists. So its meaning is changing in America today.

MS. TIPPETT: In America, but isn’t it also changing in some Islamic countries…

MS. AHMED: Yes, it is.

MS. TIPPETT: …that new generations of young women who are university-educated are making that as a choice?

MS. AHMED: You know, there have been endless books analyzing why on earth is this happening, why are they doing this? Class was one issue, that it was easier for people moving particularly from villages to the city to assume a very modest style of dress, to show that they were not departing from their traditions. All sorts of reasons are being advanced for it. I really can’t find myself thinking that it would have happened if Saudi Arabia had not had a lot of money and had it not been pouring money everywhere into promoting its kind of Islam. Maybe what I’m saying is that there’s no single source for why this is happening.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. But you do have ideas about what these young women are feeling about the veil as they choose it, and that it can be a form of public power and freedom. Whereas I think if — when a Western woman — many Western women see an image of a woman with the veil, they assume that it’s this kind of retreat from reality or a symbol of submission in a way that would have negative connotations in our culture.

MS. AHMED: Yes. I mean, you would know better than I do how a Western woman is reacting to it, and I think you’re absolutely right. That’s not an assumption I would ever make, that it is about submission. I don’t think it is about submission at all. Certainly not among the young.

MS. TIPPETT: What is it about, then, if not submission?

MS. AHMED: Well, it depends, you know, what country we’re talking about, because its meaning clearly changes by country. Because if you are a minority and you wear the veil, you’re making a statement about your being willing to take a stand for your beliefs against the current of the majority. And that’s a very courageous thing to do. It’s very different — if I were living in Saudi Arabia and put on a headscarf, it would mean something completely different. If I’m living in Egypt, where there’s probably a lot of social pressure even among the majority to wear it, it would mean something different. So I think we need to analyze it in relation to where is it that this person is putting it on? Now, one of the things I’m leaving out of this — and I should not be perhaps — is some people, no doubt, are wearing it because they believe God wants them to. But I don’t know how one gauges that exactly.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. I mean, I think those words I used a little while ago about an expression of public power and freedom could also be linked to a sense of piety or a sense of Islam as empowering in their lives. I don’t know.

MS. AHMED: Go on a bit. What do you mean?

MS. TIPPETT: Well, I don’t think there necessarily has to be a contradiction between a woman feeling empowered and feeling devout. And that is a link that a lot of Westerners maybe wouldn’t make to it.

MS. AHMED: I see. Yes, I think you’re right. Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: I mean, the whole language of submission, which is so central to Islam, it’s very difficult just linguistically in an American ear, right? Especially for American women.

MS. AHMED: Well, you know, it’s partly because I’m in the divinity, for when you say that, what I hear most is the number of graduate students I know who have worked or who are working, who are Christian, on the role of submission in Christian women, having put up with being — you know, priests tell women, ‘Well, if a husband beats you, it’s your duty to accept it.’ So…

MS. TIPPETT: Right. How teachings about submission in Christianity worked against women.

MS. AHMED: That’s right. That’s right. Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: But, I mean, my point is, also, that in Islam the word “submission,” which, again, also is a translated word, I don’t know what connotations just that word has for you and your ears.

MS. AHMED: Yes. I mean, as you know, it’s a translated word, and the word Islam in Arabic, it’s a derivative of the word “peace.” So there’s no notion of peace in submission, to me, in the English word “submission.” I mean, so the resonance of Eslam or Islam, it’s a resonance of acceptance, of something good. “Submission” is a harsh word in English, it’s about bowing to and being forced to bow to something. Whereas Islam and Eslam, which means to become Muslim, to accept Islam, has none of that resonance at all.

MS. TIPPETT: I think these are small details — they’re not really small, I think they’re key.

MS. AHMED: I think they’re vital, actually. No, because, to me, the word “submission” doesn’t translate to Islam, so it’s not small, but it’s what we live with ordinarily as if it were an equivalent word, and it isn’t.

MS. TIPPETT: Writer and scholar Leila Ahmed. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, “Muslim Women and Other Misunderstandings.”

At speakingoffaith.org, you can hear more of Leila Ahmed’s recollections of how the Arab and Muslim identity of Egyptians was created in her childhood. In her memoir, she also describes the Islamic sensibility that she learned from the women in her household in that era. The ethical vision of Islam, she says, is traditionally more a way of being than believing. Here’s a passage from that work, evoking summers spent in her mother’s family home in Alexandria.

READER: “It is easy to see now that our lives in the Alexandria house were lived in women’s time, women’s space. And in women’s culture. And the women had, too, I now believe, their own understanding of Islam, an understanding that was different from men’s Islam, ‘official’ Islam. For although in those days it was only Grandmother who performed all the regular formal prayers, for all the women of the house, religion was an essential part of how they made sense of and understood their own lives. It was through religion that one pondered the things that happened, why they had happened, and what one should make of them.

“Islam, as I got it from them, was gentle, generous, pacifist, inclusive, somewhat mystical — just as they themselves were. .Religion was, above all, about inner things. The outward signs of religiousness such as prayer and fasting might be signs of a true religiousness . but equally well might not. They were certainly not what was important about being Muslim. What was important was how you conducted yourself and how you were in yourself and in your attitude toward others and in your heart.”

From Leila Ahmed’s memoir, A Border Passage.

MS. AHMED: There was no book that I ever read that told me, ‘This is what’s important,’ but that is the message that we got simply from being alive. And actually, I can give you an example of the way that Islam is changing in our times, a talk I heard given by someone in Chicago, University of Chicago, who had studied Muslims in America since 1980 to the present. And in the course of her talk, she said, ‘When I first asked them in the early ’80s what Islam meant,’ they said to her, ‘Well, it’s about how you behave. You have to be ethical, you have to treat people well.’ ‘And that’s all they could tell me,’ she says. ‘Now, after many years of preachers coming from Saudi Arabia and elsewhere, now they know exactly what Islam is. And what is Islam? It’s the five pillars of Islam. It’s this doctrine and that creed, and this is how you recite it and this is what you do.’ So it’s a huge shift, and I think it was how people lived it and how they understood it.

MS. TIPPETT: I think that this daily lived piety that is Islamic spirituality also — I mean, I’ve felt, as I’ve come to understand that, that that’s part of what has made it so hard for Muslims to talk about Islam since 9/11, which they were put in a position where they felt that they had to do that.

MS. AHMED: That’s right. That’s a marvelous point, actually. You’re absolutely right. That’s exactly the issue there. And, actually, you know, another little detail there, it’s actually about people in Muslim societies who are not necessarily Muslim. Because I suspect that the feelings that I had as to what Islam meant were exactly what my Christian friends thought that Christianity meant growing up in Egypt, and my Jewish friends thought. So I think it’s part of the ethos of what was Islamic civilization, and it’s common to all the religions, to Hindus who grew up in a Muslim environment. So I think it’s about a whole different way of relating to the world and understanding what religion is and how one lives.

MS. TIPPETT: You said that in Egypt today, there’s a great social pressure to wear the veil now. I mean, I just wanted to ask you, what has happened in that culture that in your lifetime there’s now this different social pressure for women? What does it mean to the women you know there?

MS. AHMED: Well, I think I need to say two things. One is that I haven’t been going back much, so I read about what’s happened in that society. But, you know, there’s none of the analyses that I’ve seen that don’t have politics at the heart of it. You know, I’ve lived in America now for 25 years, and I experience America as having dramatically changed in the matters of religion and in relation to women. And I don’t know if I would call it a more pious country now, I don’t know if I’d say that, but certainly religion is much more in the air and much more important and much more powerful. Are people more deeply religious in some sense? I doubt it, actually. But I don’t know how you would speak about how your experience in America is.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, there’s a different kind of public expression and a kind of energy that maybe was below the surface, which is out on the surface now.

MS. AHMED: Was it there below the surface?

MS. TIPPETT: I think it was. But, I mean, I think the point you’re making is just to remind us that there’s a parallel surge of religious energy, or of visible religious energy, in our culture, which we observe in what we call the Muslim world.

MS. AHMED: Yes. But also, I think I’m trying to suggest that I don’t experience it in America as separate from politics. I don’t think it’s about people having become more deeply religious, I think it’s about who has the power more.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

MS. AHMED: And I think very much that’s the case anyway in the Muslim world, about a shift in power, partly because of the amount of money that the most religious fundamentalist countries have had. The oil money has been chiefly fundamentalist.

MS. TIPPETT: Egyptian-American writer and scholar Leila Ahmed. This is Speaking of Faith. After a short break, more conversation with Leila Ahmed, including the myth of the Islamic world and why she worries about women in America.

Visit us online at speakingoffaith.org. View a slideshow of Diana Matar’s exquisite photographs showing Muslim women wearing the veil in contemporary Egypt. And read Leila Ahmed’s discourse on the veil and why people in the West often misinterpret it. Also, sign up for our weekly e-mail newsletter with my journal, and subscribe to our free podcast so you’ll never miss another program. Listen when you want, wherever you want. Discover more at speakingoffaith.org. I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us. Speaking of Faith comes to you from American Public Media.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “Muslim Women and Other Misunderstandings.”

I’m speaking with Egyptian-American writer and scholar Leila Ahmed. She’s one of the most incisive contemporary scholars of women and gender in Islam, and the first Muslim woman on the faculty of Harvard Divinity School. She’s offering a provocative critique of American perceptions about the Islamic world in general and Muslim women in particular. She first came to question her own assumptions about such things when she set out to write her life story in the 1990s. The religious dynamics of her native country, Egypt, have changed dramatically in her lifetime, but she knows the complexity that lies in its history and its people.

Here’s a reading from a chapter in her memoir entitled “Harem.” She’s recalling formative times spent in the company of extended circles of women in her family.

READER: “Looking back now, with the assumptions of my own time, I could well conclude that the ethos of the world whose attitude survived into my own childhood must have been an ethos in which women were regarded as inferior creatures. …But my memories do not fit with such a picture. I simply do not think that the message I got from the women … was that we, the girls, and they, the women, were inferior. But what, then, was the message? I don’t think it was a simple one.

“…It is quite possible that while the women did not think of themselves and of us as inferior, the men did, although — given how powerful the cultural imperative of respect for parents, particularly the mother, was among those people — even for men such a view could not have been altogether uncomplicated. But men and women certainly did live essentially separate, almost unconnected lives. … Living differently and separately and coming together only momentarily, the two sexes inhabited different if sometimes overlapping cultures, a men’s and a women’s culture, each sex seeing and understanding and representing the world to itself quite differently.”

MS. TIPPETT: From the memoir A Border Passage by my guest today, Leila Ahmed. Now back to our conversation.

MS. TIPPETT: You have a chapter in your memoir which you call “Harem.” You know, there’s another word that kind of comes down to us through literature and fairy tales, and also it’s kind of an image of what we think might be wrong and might have always been wrong with women in, you know, Middle Eastern Arabic societies, right?

MS. AHMED: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: The chapter you write, then, that you title “Harem,” is really about the closeness of women in the circles in which you grew up. I mean, what do you think of — I mean, I’d love to hear a story or a particular people when you use the word “harem.”

MS. AHMED: Well, as I describe there, it actually is a very warm and — it’s a wonderful environment because it was about being with all the women of the family and the children very comfortably. There was usually, you know, at least half a dozen aunts and grandmother and so on. Let me say a couple of things, which is not a story about that world, but about how people have responded to me here, which is that people have said to me, ‘Well, you know what, that’s what it was like when I was a kid in my family in Vermont’ or in Minnesota, or wherever it is. Because we did gather, it was the women who gathered. We’d gather in the kitchen, or we’d be — and there would be that atmosphere of free discussion and talking that I describe as being part of what it was to be in a women’s community in Cairo, where I grew up, or Alexandria. That this is actually a common experience of many societies just before we became nuclear families, each of us in our little boxes. That a lot of people have these memories of families being extended families, and of people, you know, dividing up by sex to talk about whatever their interests were.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. What does the word “harem” mean?

MS. AHMED: Well, it means women’s quarters.

MS. TIPPETT: That’s what it means.

MS. AHMED: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: So it doesn’t necessarily mean the concubines’ room.

MS. AHMED: It certainly doesn’t mean the concubines’ room, no. That was a Western male fantasy. They invented what it was that harems meant. All the Western men who traveled to the Muslim world who were unable to get into a harem had fantasies as to what was going on in there. So this is where our American heritage of the word “harem” comes.

MS. TIPPETT: But, you know, I do think that it’s true, and correct me if I’m wrong, but in — and again, you’re going to say every Muslim country is different, every culture is different — but that in Muslim cultures that there is a greater separation between men and women now than there is here.

MS. AHMED: I think that’s probably true. That’s probably true, yes.

MS. TIPPETT: That’s something that Americans will look at, American feminists, and say, ‘That’s a problem.’ Is that a problem, in your mind?

MS. AHMED: No, it isn’t. I mean, first thing that comes to my mind if you say American feminists would say it’s a problem, they probably would, but, on the other hand, what was striking to me when I first came to this country was that people kept telling me about these wonderful consciousness-raising groups that they had, and I said, ‘Well, what are they?’ And they said, ‘Well, you know, women get together and talk about their experiences.’ So apparently it was a very powerful thing for the American feminist movement for women to get together without men and talk.

So why is it that when women get together in other countries, we’re unable to see that that’s women getting together and talking? We think it’s a bad thing. I don’t quite know. I don’t know if feminists are quite primitive now, even, I mean American feminists, whether they have got to the point of understanding that there’s good use and insight in being able to get together and criticize, which is what a lot of Muslim women do when they get together, either the political system or the men in their families or the conduct of men and so on.

MS. TIPPETT: I think we also look at Islamic fundamentalism and see men off on their own without women, and find that to be dangerous. I mean, that’s the other side of that story.

MS. AHMED: Yes, that’s true, but it’s not dangerous if it — unfortunately, they have fundamentalist men and, you know, they have power, so that’s what’s dangerous. I don’t care if they get together; they’re welcome to do so.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MS. AHMED: But if they keep hold of all the power, that’s what scares me, and that’s what I don’t like. And I’m glad you make that point because there is no necessary connection between fundamentalism and a slightly segregated society. Fundamentalism is hideous. I mean, I think it’s a very dangerous thing, fundamentalist ways of looking at society. But I don’t think — until we have a perfect world, I don’t think some slight segregation is so terrible.

MS. TIPPETT: You’re talking about segregation between men and women.

MS. AHMED: Between men and women, yeah. But, I mean, it does vary, as you said to begin with, across Muslim countries. And I think one of the problems of a country, say, like Egypt is facing now is that, in fact, there is a breakdown of the extended family, and that’s causing havoc because women have to go to work. They used to be able to leave their children with their mothers or their mother’s sisters or somebody. You know, the network of women is no longer there. So I don’t think the segregation is anything like — or the possibility of women — links between women is anything like as strong as it used to be.

MS. TIPPETT: I mean, if you had to say, from your perspective, what you do worry about for women in the Islamic world — there I go generalizing again — I mean, what comes to your mind? And again, you know, not issues of poverty or what you talked about, the breakdown of the extended family, I mean, we have that in this culture, too — but what do you worry about that is related to the religion of Islam?

MS. AHMED: Well, obviously fundamentalism being entrenched in power. That is very dangerous and very frightening. But how does one exactly separate, I mean, I can’t quite remove poverty because if there were no poverty, the situation would be completely different. I wouldn’t be as frightened as I am. But I do think, in many countries, Islam is used as a way of justifying outrageous behavior, and the combination of poverty, of lack of education, makes it impossible to speak out against that or for women to know that this is not Islam. So I can’t quite remove poverty and lack of education from…

Well, you know, I would like to turn that question around to you. When you think about America, what do you fear most for women?

MS. TIPPETT: Probably the same things you just described. That we don’t have any support to take care of our children and go out to work, and that there are a lot of women living in poverty, and I don’t really know how they get through the days, honestly.

MS. AHMED: Yes. Yes, I agree with you. Now, do we fear fundamentalism for America too? I mean, are we afraid of what happens in the Supreme Court, of what abortion rights going to happen? You know, are these fears only for over there? Creationism?

MS. TIPPETT: I think it’s easy to politicize some of what’s happening and make it seem more frightening than it in fact is. But when I was reading your book, it was very striking to me, the incredible social upheaval that you lived through. I mean, the real transformation of your culture, of Egypt. That happened over time, right? And I mean, there were dramatic moments. I mean, there were wars that were fought and lost and political changes, but all of it resulted in a complete transformation. And that did, in fact, make me think about how we take very much for granted the idea that whatever happens here, it will be OK, that we will basically come out in the same place with the same system.

MS. AHMED: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: But people in other cultures have a different experience. You have a different experience of how the world can change around you.

MS. AHMED: That’s right. But, you know, I used to think that about America that things would be always OK, but the last few years have been very frightening.

MS. TIPPETT: Egyptian-American writer and scholar Leila Ahmed. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media, today in conversation with Leila Ahmed about “Muslim Women and Other Misunderstandings.”

MS. TIPPETT: I mean, I think it’s really interesting that we’re having a conversation about what frightens you about women and the Islamic world, and you’re telling me that that’s not the only place you’re looking now.

MS. AHMED: Yes. Well, look, for one thing, I no longer believe that there’s an Islamic world, because where exactly are the borders? Are they in Chicago? Where are they? Where does the Islamic world end and where does the West begin? Is it in Paris, or where is it? So I do think what happens in this country is going to be as much about the Islamic world as whatever happens over there. The Islamic world is no longer over there, that’s one thing.

The other thing is, I think what we do, what we Americans do, will profoundly determine what becomes of what we’re calling Islamic world. Who our allies have been has been very important. I think of Saudi Arabia, the country that America’s been most staunchly allied with for decades. I mean, I think, in some ways, my native country, Egypt, has been decimated in part because of the flow of petrol dollars into Egypt, which has given rise to fundamentalism. We saw terrible terrorism attacks throughout the ’90s in Egypt, partly fueled, my guess is, by money from that region. I don’t think we would have witnessed what we’ve witnessed. But — so there’s no — it’s not what will Egypt do or what will Saudi Arabia do? What will American do is absolutely vital to what becomes of our world collectively. It’s no longer borders, really.

MS. TIPPETT: I mean, so that’s where — you’re looking at how other countries see us and seeing a very different way to critique the present and to describe what has gone wrong. That Saudi Arabia has been such a huge ally to the United States is a problem for us in the Muslim world, you’re saying.

MS. AHMED: Yes. It’s a problem for us here. We’ve got terrorism here in this country. A lot of them are Saudis. So I’m saying that there’s no place where one can say, you know, America’s here and Islam is over there, and what we do over there doesn’t matter. It’s going to touch us directly here. And it touches the rest of the world too. But I don’t think we’re insulated, and I think it’s — what we do shapes the world, at home and abroad.

MS. TIPPETT: As you watch the American presence in Iraq, we’re engaged there, we are implicated in and involved in the creation of a new Iraqi government, a new Iraqi system and perhaps culture. What would you like Americans to be thinking about and watching for in terms of women, but also just the preservation of what you think of as the best of Islamic sensibility, what you often refer to as the ethical sensibility of Islam?

MS. AHMED: Well, if we focus on the women, what’s happening there seems to be heading towards disaster. You know, the Iraqi women have been among the — in the lead of liberated Muslim women. Actually, they’re not Muslim. And I guess one of the difficulties here is that, you know, I don’t think of the Middle East as Muslim. It’s been, for thousands of years, a mixture of religion. Iraq has been, you know, Christians are very important, Jews were very important. It’s not there now. But so whatever culture — and what I call ethical Islam is actually an ethical mixed heritage. It’s about how people of different religions have lived together for millennia, and that’s what I cherish. And that has been destroyed. I hope not irretrievably. I don’t quite know how we’re going to come back, but I think it’s latently present. They did it for literally thousands of years, as old as Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, so they’ve been doing it for a good long time. So I’m unable to say how does one restore ethical Islam to Iraq. Well, I think it’s there living in the people, but I don’t think that the average Iraqi woman is concerned more — at the moment what they want most is safety, peace, clean water, electricity. And let us give them that, if we can, and then allow them to figure out how to run their country.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, let me ask you this. I think there might be, again, a kind of knee-jerk response that Americans might have that Islamic law, I mean, any religious law, but that Sharia law as part of the constitution, as part of the new system would automatically be bad for women. Is that true?

MS. AHMED: Well, there are two ways of answering that. Sharia law is in itself a hugely complex, vast body of law, some of which is liberal, some of which is not. It depends how you put it together. So it’s a huge volume of laws composed in the medieval era. Some of the judges were very enlightened and tried to give justice to women, and some did not. And out of that, one could piece together a law that treats women with justice. But I don’t see that, at this moment, we are able to do that. Tunisia has done a version of that, but someone introducing Sharia law at this moment into Iraq, I think, is very likely to use the most conventional and the most biased-against-women version of it. And I think that, really, there the peril is. If we were to see somebody now insisting that we have to introduce into the American Constitution that everything has to agree with Christianity, then they’re not out to bring in the most liberal interpretations.

MS. TIPPETT: You’ve talked about fundamentalism among Muslims, and everyone sees that. And also, you’ve talked about things that are disturbing in our country. But I wonder, are there places you look for hope, and that help you maybe see the picture differently?

MS. AHMED: Well, really, you know, as we’ve been talking about, say, Iraq or how the veil is seen, I guess dominant in my own mind has been the politics of it. And the politics have not been pleasant. But through exactly this same time of being in America, I’ve been astounded and moved and inspired by the kind of — on the ground people have been quite open. You know, we’ve been talking about prejudice against Islam in America, but actually what I’ve encountered on a living basis as I have observed non-Muslim Americans interact with Muslims or as well as with myself, is their extraordinary openness and that they’re not tied down by the kinds of things we’ve been talking about, that they’re not tied down by prejudices. So I do think we’re actually living through quite a transformation in America, but it’s not obvious on the surface. It’s not what’s happening on the politically explicit level.

MS. TIPPETT: And it’s not what makes the headlines and the news stories.

MS. AHMED: That’s right, that’s right. But, in fact, on the ground it’s really marvelous, actually.

MS. TIPPETT: I mean, that’s quite a strong word, really.

MS. AHMED: It is. It is. Well, it is marvelous, what’s going on. So that’s where my hope lies.

MS. TIPPETT: Leila Ahmed holds the Victor S. Thomas chair at the Harvard Divinity School. Her insights challenge us to question American cultures, instincts, and analyses about who Arabs and Muslims are if we really want to understand Islam as a force in women’s lives and in our world. Leila Ahmed’s books include Women and Gender in Islam: Historical Roots of a Modern Debate and a memoir, A Border Passage. Here in closing is a reading from that work.

READER: “It has not been only women and simple unlearned folk who have believed, like the women who raised me, that the ethical heart of Islam is also its core and essential message. Throughout Muslim history, philosophers, visionaries, mystics, and some of the civilization’s greatest luminaries have held a similar belief. But throughout history, too, when they have announced their beliefs publicly, they have generally been hounded, persecuted, executed. …From almost the earliest days, the Islam that has held sway and that has been supported and enforced by sheikhs, ayatollahs, rulers, states, and armies has been official textual Islam.

“…There has never been a time when Muslims, in any significant number, have lived in a land in which freedom of thought and religion were accepted norms. Never, that is, until today. Now, in the wake of the migrations that came with the ending of the European empires, tens of thousands of Muslims are growing up in Europe and America, where they take for granted their right to think and believe whatever they wish and take for granted, most particularly, their right to speak and write openly of their thoughts, beliefs and unbeliefs.

“For Muslims this is, quite simply, a historically unprecedented state of affairs. Whatever Islam will become in this new age, surely it will be something quite other than the religion that has been officially forced on us through all these centuries.”

MS. TIPPETT: From Leila Ahmed’s memoir, A Border Passage.

Contact us and share your thoughts at speakingoffaith.org. Our Web site features unheard cuts of my conversation with Leila Ahmed and you can view Diana Matar’s photos of modern Egyptian women wearing the veil in daily life. We also offer a weekly podcast and an e-mail newsletter containing my journal on each week’s topic. Sign up for free so you’ll never miss another program again. Listen when you want, wherever you want. Discover more at speakingoffaith.org.

The senior producer of Speaking of Faith is Mitch Hanley, with producers Colleen Scheck and Jody Abramson and editor Ken Hom. Our online editor is Trent Gilliss, with assistance from Jennifer Krause. Kate Moos is the managing producer of Speaking of Faith, our executive editor is Bill Buzenberg, and I’m Krista Tippett.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.