M. Soledad Caballero

Someday I Will Visit Hawk Mountain

In the face of wonder, we can sometimes lose ourselves.

We’re pleased to offer M. Soledad Caballero’s poem, and invite you to sign up here for the latest from Poetry Unbound.

Letterpress print by Myrna Keliher. Photography by Lucero Torres. © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

M. Soledad Caballero is Professor of English and chair of the Women’s Gender and Sexuality Studies Program at Allegheny College. Her first collection, titled I Was a Bell, won the 2019 Benjamin Saltman Poetry Award. Her scholarly work focuses on British Romanticism, travel writing, post-colonial literatures, Women’s Gender and Sexuality Studies, and interdisciplinarity. She splits her time between Pittsburgh and Meadville, Pennsylvania.

Transcript

Transcription by Heather Wang

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and for a long time, but especially during the lockdowns of COVID, I’ve been looking at birds — mostly tiny little birds that come and eat the seeds that I leave out in the backyard for them. I’ve gotten to recognize their antics and their fights and their actions with each other, and the speed and the skill. I know the ones that can hang upside-down and the ones that eat from the ground.

One time, I was walking, and I heard this plaintive cry up in the sky, and I looked up, and it was a buzzard. And it was just inscribing massive shapes in the sky. And it was calling out. I’m not sure what it was calling out for, if for anything; maybe it was just doing what it does. But I couldn’t move, watching this bird of beauty and power and prey moving around the sky in large circles.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Someday I will visit Hawk Mountain” by M. Soledad Caballero:

“Someday I will visit Hawk Mountain”

“I will be a real birder and know raptors

by the shape of their wings, the span of them

against wide skies, the browns and grays

of their feathers, the reds and whites like specks

of paint. I will look directly into the sun, point and say,

those are black vultures, those are red-shouldered

hawks. They fly with the thermals, updrafts, barely

moving, glide their bodies along the currents, borrowing

speed from the wind. I will know other raptors,

sharp-shinned hawk, the Cooper’s hawk, the ones

that flap their wings and move their bodies during the day.

The merlins, the peregrine falcons, soaring like bullets

through blue steel, cutting the winds looking for rabbits,

groundhogs that will not live past talons and claws.

I will know the size of their bones, the weight

of their beaks. I will remember the curves, the colors

of their oval, yellow eyes. I will have the measurements,

the data that live inside their bodies like a secret

taunting me to find its guts. Or this is what I tell myself.

But, I am a bad birder. I care little about the exact rate

of a northern goshawk’s flight speed. I do not need

to know how many pounds of food an American kestrel

eats in winter. I have no interest in the feather types

on a turkey vulture. I have looked up and forgotten

these facts again and again and again. They float

out of my mind immediately. What I remember:

my breathless body as I look into the wildness above,

raptors flying, diving, stooping, bodies of light, talismans,

incantations, dust of the gods. Creatures of myth,

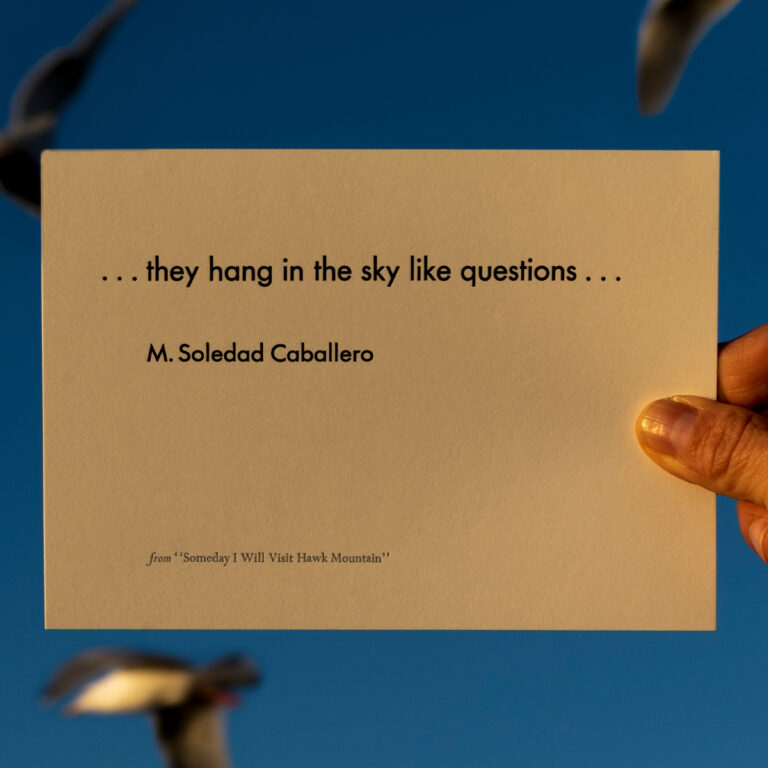

they hang in the sky like questions. They promise

nothing, indifferent to everything but death.

Still, still, I catch myself gasping, neck craned up,

follow the circles they build out of sky, reach

for their brutal mystery, the alien spark of more.”

[music: “Dust of Summer” by Gautam Srikishan]

I love this poem by Soledad Caballero. I read through the whole book so many times, and gave it to friends as gifts after I’d bought it. And this poem is one of the ones I kept on coming back to. There’s great irony in the poem, because it says: “But, I am a bad birder,” and even the opening line, “I will be a real birder and know raptors.” There’s the sense, initially, where you think, oh, this person is going to tell us about all the things they don’t know. But that’s not quite true, because even though she doesn’t feel like a real birder, there’s the listing of all the things that she knows she doesn’t know. [laughs] She’s showing an extraordinary coverage of the facts: like about raptors, the shape and span of their wings, and the color of their features; and vultures and hawks, how they fly. And then there’s other birds mentioned, too — kestrel, merlins, peregrine falcons, turkey vultures and their prey. And we hear about feather colors, and how they fly with thermals — “glide their bodies along the currents, borrowing / speed” from wind. So, sometimes when I read this poem, I think I would love to know half of what she says she doesn’t know, because she knows so much.

And I love the repetition of “I will” that happens six times in the poem: “I will be a real birder,” “I will look directly into the sun,” “I will know other raptors,” “I will know the size of their bones,” “I will remember the curves,” “I will have the measurements.” The repetition of these six “I will’s” sounds almost like a contract. But that contract is broken, because the “I will,” the “I will,” the “I will’s,” all of them are saying that “I will have more knowledge.” The person clearly has plenty of knowledge, but what happens is that knowledge becomes secondary when she really looks up.

[music: “Cornicob” by Blue Dot Sessions]

There’s a kind of an irony in the poem, about knowledge and experience. The poem isn’t putting down knowledge, but the poem is linking knowledge to experience. And so to know something about a thing, to know something about all these birds, is not the same as witnessing and experiencing them. Obviously, they can each support each other. But she continues to repeat that looking up means that she forgets these facts, again and again and again: “They float / out of my mind immediately.” Even the facts take flight, as she looks at birds in flight. And this isn’t a poem about not knowing; it’s a poem about forgetting, when you see, and being enthralled to the event of watching. The facts about a thing are not the thing; they should help you appreciate the thing. And in this she knows so much.

But even knowing so much, all of that becomes minimal in comparison to the orchestra of observing these birds. She is a living, breathing creature, watching other living, breathing creatures, who can make use of air. And they are utterly unalike, and they’re utterly praiseworthy, and they’re beautiful and brutal, all at once — “[c]reatures of myth,” she calls them, “indifferent to everything but death.” She’s not trying to create a pretty relationship with them. They are indifferent to her, even though she is particularly given to being enthralled by them and learning all about them, clearly.

And somehow, in the midst of all that space and separation, she’s asking the question of self, while she beholds the brilliance of these questions that hang in the air; these birds. Rilke used to do this sometimes; he’d speak about God and then immediately bring in the question of self. And Soledad Caballero is doing the same thing here — looking at these visual demonstrations of beauty and brutality and brilliance, and then recognizing the question of self, in relation to the watching. She’s watching the watcher, herself, as well as watching the watched.

[music: “The House You Wake In” by Gautam Srikishan]

I don’t know why, and I know I’m adding this to the poem, but I keep on thinking about an orchestra, whenever I see those birds through this poem. And I think of the magnificence of the birds forms an event, forms something beautiful and orchestral — [laughs] I keep on turning towards that word. And the language itself rises and just continues to give and give and give:

“raptors flying, diving, stooping, bodies of light, talismans,

incantations, dust of the gods. Creatures of myth,

they hang in the sky like questions. They promise

nothing, indifferent to everything but death.”

The birds are being demonstrated as the perfect in-between. They’re physical and beyond. They’re in sight, but not in touch. And so no wonder this poem goes from verbs like “flying, diving, stooping,” to then these mythical descriptions: “talismans, / incantations, dust of the gods.” She’s torn between the physical reality and grasping at mythological references, to try to describe the thing that she’s witnessing. It is both true and magic all at once; and it is present, but utterly ungraspable.

The medium of this poem is air, and the direction is up. It’s a poem of wonder. And the data, while it’s so important, the data is being asked to be absorbed into the body that will then need to look up, to pay attention to the thing that the data’s describing. And looking up, this poem says that everything else that came before takes second place, as you watch this “alien spark of more.”

[music: “Thread Caramb” by Blue Dot Sessions]

“Someday I will visit Hawk Mountain” by M. Soledad Caballero:

“Someday I will visit Hawk Mountain”

“I will be a real birder and know raptors

by the shape of their wings, the span of them

against wide skies, the browns and grays

of their feathers, the reds and whites like specks

of paint. I will look directly into the sun, point and say,

those are black vultures, those are red-shouldered

hawks. They fly with the thermals, updrafts, barely

moving, glide their bodies along the currents, borrowing

speed from the wind. I will know other raptors,

sharp-shinned hawk, the Cooper’s hawk, the ones

that flap their wings and move their bodies during the day.

The merlins, the peregrine falcons, soaring like bullets

through blue steel, cutting the winds looking for rabbits,

groundhogs that will not live past talons and claws.

I will know the size of their bones, the weight

of their beaks. I will remember the curves, the colors

of their oval, yellow eyes. I will have the measurements,

the data that live inside their bodies like a secret

taunting me to find its guts. Or this is what I tell myself.

But, I am a bad birder. I care little about the exact rate

of a northern goshawk’s flight speed. I do not need

to know how many pounds of food an American kestrel

eats in winter. I have no interest in the feather types

on a turkey vulture. I have looked up and forgotten

these facts again and again and again. They float

out of my mind immediately. What I remember:

my breathless body as I look into the wildness above,

raptors flying, diving, stooping, bodies of light, talismans,

incantations, dust of the gods. Creatures of myth,

they hang in the sky like questions. They promise

nothing, indifferent to everything but death.

Still, still, I catch myself gasping, neck craned up,

follow the circles they build out of sky, reach

for their brutal mystery, the alien spark of more.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Chris Heagle: “Someday I will visit Hawk Mountain” comes from M. Soledad Caballero’s book I Was a Bell. Thank you to Red Hen Press for giving us permission to use Soledad’s poem. Read it on our website, at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, and me, Chris Heagle.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions.

This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. You may enjoy our other podcasts: On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me. Find those wherever you’d like to listen, or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.