Margaret Atwood

All Bread

In a poem of four stanzas, Margaret Atwood traces bread from its growth in bone-nurtured soil, to the warm ovens of baking, to the table, to the mouth of one person, then the hands of someone breaking bread for many. From the cow-dung in the earth to the salt of the hands of the person kneading the bread, this poem is like a meditation on the material reality of what nurtures the body and what nurtures the soul, and is a secular examination of what breaking bread might mean.

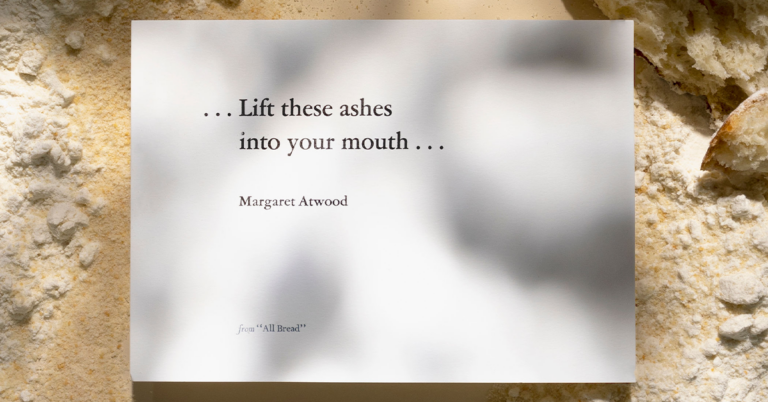

Letterpress prints by Myrna Keliher | Photography by Lucero Torres

Guest

Margaret Atwood is the author of more than fifty books of fiction, poetry, critical essays, and graphic novels. Her latest novel, The Testaments, is a co-winner of the 2019 Booker Prize. It is the long-awaited sequel to The Handmaid’s Tale, now an award-winning TV series. She lives in Toronto.

Transcript

Pádraig Ó Tuama, host: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and I used to think that poetry — and religion, too — was about describing the transcendent; you know, the things you couldn’t put your hands on. But these days, I find myself more and more interested in poems and religion that are paying attention to the things you can put your hands on, the things you can taste, the things that appeal to the senses, and not trying to capture them or trying to say, Here’s what they mean, but trying to pay attention to them and to be beheld by them, as you behold them.

“All Bread,” by Margaret Atwood:

“All bread is made of wood,

cow dung, packed brown moss,

the bodies of dead animals, the teeth

and backbones, what is left

after the ravens. This dirt

flows through the stems into the grain,

into the arm, nine strokes

of the axe, skin from a tree,

good water which is the first

gift, four hours.

Live burial under a moist cloth,

a silver dish, the row

of white famine bellies

swollen and taut in the oven,

lungfuls of warm breath stopped

in the heat from an old sun.

Good bread has the salt taste

of your hands after nine

strokes of the axe, the salt

taste of your mouth, it smells

of its own small death, of the deaths

before and after.

Lift these ashes

into your mouth, your blood;

to know what you devour

is to consecrate it,

almost. All bread must be broken

so it can be shared. Together

we eat this earth.”

[music: “At Dusk” by Gautam Srikishan]

You know, I remember the first time I ever read anything by Margaret Atwood, which was years ago. The Blind Assassin, which is one of her novels, had just come out. And so I then, after that, began to read as much of hers as I could, which is difficult, because there’s so much. And I had not known she was a poet until I started to go to the library and find some more of her poetry books.

And this is the poem of hers that I keep on coming back to. There’s something about it that feels like it’s an insight into the way she sees the world, as well as something she wants to say to the world about the world, which is about material reality and seeing the value and power in paying attention to material reality.

There’s these references to “nine / strokes of the axe” and “good water” and “four hours,” and even “the heat from an old sun.” In a certain sense, this is a poem that is almost like a recipe. There’s little calculation points along there — how to chop something down, how long to leave it, rising times, how hot should the oven be when you put it in. So there’s just these little oblique references spread throughout it like a bit of salt. And I think that’s a lovely thing to do, because it amplifies the genre of literature that is recipe to the level of poetry, because you read a recipe with such extraordinary attention to the detail of it. And that is a way of honoring language in recipe and language in poetry and the language we use about hunger.

[music: “Outstretched Hand” by Gautam Srikishan]

So this poem is in four verses. The first verse describes growing grain from which the bread is made. And then the second describes baking bread, the third verse describes tasting the bread, and then the fourth verse describes sharing it. So there’s four particular movements throughout this poem. And it describes the process of bread-making in a way where very simple and this very necessary act is practical — where it comes from, how you make it, how you bite it, how you share it. And one of the things that this poem resists is the idea of seeing bread as a transcendent image or sacrament.

It doesn’t pay attention to that at all. It pays attention to the real material reality of the dark earth from which the grain comes, of the tastes of that, of watching the belly of the bread rise, of paying attention to sometimes brutal images of life and death that she uses, and then even thinking about the taste of salt from your skin and breaking the bread to share it and that the bread is almost like ashes you lift into your mouth, because it’s got death in it, as well as life.

And that, I think, is something that she is really focused on, in terms of saying, Pay attention to this tangible, taste-ful thing, and that the surface reading of this is not shallow. For her, I think, in this poem and in so much of her writing, the surface reading of something is actually filled with layer upon layer upon layer of meaning, without needing to raise it up to the idea of a theological proposal. And instead she’s saying, Actually, the material reality here already is over-full with stories of life and death and meaning and gratitude and sharing and difficulty.

[music: “Into the Earth” by Gautam Srikishan]

The poem has fairly arresting and sometimes even harsh imagery. There’s wood and cow dung and moss in the first stanza, but then there’s also the bodies of dead animals and the leftovers of what other animals had picked and discarded. And she’s describing the earth, and I don’t mean the planet, I mean the actual earth, and the dead things, the nutrients from which are nurturing the earth from which then grain might grow. And that is a really brave thing to do, because there is this idea, perhaps, of the purity of a freshly baked loaf of bread, and she’s saying, “No, let me talk about the impurity of the places from which grain comes.”

There is a reality that is not in any way romantic to the way that Margaret Atwood speaks about the Earth — “bodies of dead animals,” their teeth and backbones and what’s left “after the ravens,” and “famine bellies / swollen and taut,” and “small death” and “ashes into your mouth.” Even words in the final stanza like “blood” and “devour” and “broken” — there’s many things that you can read into the choice of these kinds of words, but one of them is that this is not a poem of sentimentality. It’s not a pretty poster to hang up. This is a poem that says, pay attention to what’s happening. Pay attention to what you eat. Pay attention to your hunger. And find a way that, in satisfying your hunger, you can also share.

And that’s one of the things that Margaret Atwood is saying in a pretty strong way. Even in the second stanza, she talks about “live burial” and that really uncomfortable image of the rising bread looking like “famine bellies.” I hate reading that, “famine bellies / swollen and taut,” because she’s bringing in the reality of hunger, and hunger that’s satisfied as well as hunger that will not be satisfied, into this poem; and then salt from our skin, and the bread smelling of “its own small death, of the deaths / before and after.”

And then finally, the way that she speaks about, in the final stanza, “Lift these ashes / into your mouth,” it is almost a contradiction from perhaps a Christianity that might say, “Lift the body of Christ into your mouth.” She’s saying it isn’t life that will give us life, it’s death, and that somehow, knowing what it means to eat something that has been nurtured by death is to consecrate it, knowing that we, too, in our bodies, will eventually become something that feeds the earth, also.

And there she turns towards the purpose of all of this, which is to share: “Together / we eat this earth.” And quietly lurking in that is: together, we’ll also become it.

[music: “Memoriam” by Gautam Srikishan]

I heard Margaret Atwood describe herself once as a “strict agnostic.” She was being interviewed by Bill Moyers. And he said to her, “If you could eliminate the hunger for God in the human person, would you?” And I mean, he was being a bit hyperbolic in that. But she replied by saying you could only eliminate the hunger for God by also eliminating language.

[laughs] I thought that was the most extraordinary reckoning. She isn’t talking about God, she is talking about the desire for God, the desire for prayer, the desire for ritual that you see exhibited in all human populations, going in all kinds of different directions about their imagination about what God is. But somehow, this shared hunger is present, and this shared hunger is linked to the desire to put language on something, perhaps, and is as dangerous, as well as delightful, in that project. And I think that’s such an interesting thing that she speaks of: the reckoning with human longing is going to be a reckoning with language, as well as that with what we might call God.

[music: “Waterbourne” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Margaret Atwood puts this powerful word, “consecrate,” “to make something holy,” into the poem in the last stanza, which I think is a lovely nod to the fact that bread-sharing rituals are a part of many religions and are amplified to something that is holy, in many religions. And she puts the word “consecrate” alongside “devour”: “to know what you devour / is to consecrate it, / almost.”

And there is such care in that. And what she’s saying is, Know what you’re doing; and that perhaps in the knowing, perhaps in the paying attention to the very plain reality of where this thing came from, something that’s almost holy, almost consecrated, might be put out there. I love the humility and the tenderness and the accuracy from which she’s speaking from her own point of view: “almost.” She’s not wanting to put across a new creed, a new doctrine. She’s just wanting to say, This in itself is a good thing. Try it, and do it, and see what happens.

I think one of the invitations in this poem is to look at one small thing, a loaf of bread, and then to see all of the things that are gathered within that small thing — the place from which it came, the bodies of the animals that nurtured the earth from which the wheat grew, who made it, whose taste are we tasting in it, whose hunger is it satisfying, how could it be shared — that looking at the one small thing, you can find so much else gathered into it.

[music: “At Dusk” by Gautam Srikishan]

“All Bread,” by Margaret Atwood:

“All bread is made of wood,

cow dung, packed brown moss,

the bodies of dead animals, the teeth

and backbones, what is left

after the ravens. This dirt

flows through the stems into the grain,

into the arm, nine strokes

of the axe, skin from a tree,

good water which is the first

gift, four hours.

Live burial under a moist cloth,

a silver dish, the row

of white famine bellies

swollen and taut in the oven,

lungfuls of warm breath stopped

in the heat from an old sun.

Good bread has the salt taste

of your hands after nine

strokes of the axe, the salt

taste of your mouth, it smells

of its own small death, of the deaths

before and after.

Lift these ashes

into your mouth, your blood;

to know what you devour

is to consecrate it,

almost. All bread must be broken

so it can be shared. Together

we eat this earth.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Chris Heagle: “All Bread” comes from Margaret Atwood’s book Two-Headed Poems. Thank you to Penguin Canada, who gave us permission to use Margaret’s poem. Read it on our website, at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, and me, Chris Heagle.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions. This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land.

We also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me. Find those wherever you like to listen, or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.