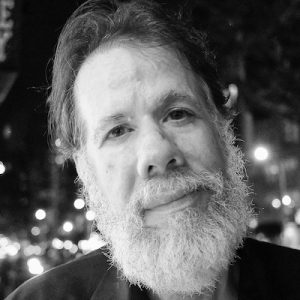

Martín Espada

After the Goose that Rose Like the God of Geese

Bereavement brings all kinds of pressures. This poem by Martín Espada starts off with a grief-to-do-list: a phone call, a flight, a blizzard, cremations, shipments of ashes, memorial services. After all of this — in a first stanza that builds in intensity — he needs to be reconnected with something tangible. He goes to feed birds at the park, and among the birds is a goose, like a god of the geese, who shrieks with all the emotion stored in him. This goose is like a priest of grief for Martín Espada, voicing the sounds of all that he’s feeling.

Letterpress prints by Myrna Keliher | Photography by Lucero Torres © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Martín Espada has published more than twenty books as a poet, editor, essayist and translator. His new book of poems from Norton is called Floaters. Other books of poems include Vivas to Those Who Have Failed, The Trouble Ball, and Alabanza. A former tenant lawyer in Greater Boston, Espada is a professor of English at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

Transcript

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and one of the things I love about poetry is that it can be, in a single poem, like a marriage between unexpected things: a marriage between the living and the dead or the marriage between hope and brutal reality or the marriage between friendship and the griefs that friendships carry. And it doesn’t try to resolve it, to say it has to be one thing or the other. Poetry can say: it can be a few things together, in these unexpected marriages.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

“After the Goose That Rose Like the God of Geese,” by Martín Espada.

This poem has an epigraph from William Blake: “Everything that lives is Holy.”

“After the phone call about my father far away,

after the next-day flight canceled by the blizzard,

after the last words left unsaid between us,

after the harvest of the organs at the morgue,

after the mortuary and cremation of the body,

after the box of ashes shipped to my door by mail,

after the memorial service for him in Brooklyn,

“I said: I want to feed the birds, I want to feed bread

to the birds. I want to feed bread to the birds at the park.

“After the walk around the pond and the war memorial,

after the signs at every step that read: Do Not Feed The Geese,

after the goose that rose from the water like the god of geese,

after the goose that shrieked like a demon from the hell of geese,

after the goose that scattered the creatures smaller than geese,

after the hard beak, the wild mouth taking bread from my hand,

“there was quiet in my head, no cacophony of the dead

lost in the catacombs, no mosquito hum of condolences,

only the next offering of bread raised up in my open hand,

the bread warm on the table of my truce with the world.”

[music: “The House You Wake In” by Gautam Srikishan]

I love the cumulative nature of this poem, the 12 times that the word “after” is used. It builds and it builds and it builds, and you wonder what’s going to happen. And it’s a poem about living with grief. And obviously, the father has died, but this is less a poem about the father and more a poem from Martín Espada about himself and the kind of things you feel compelled to do — strange things, sometimes, when you’re in the shock of grief and you’re trying to make sense of the world, and you’ve just come back from a funeral or you’ve just gotten bad news, and all of the things to do, are done. And you have this impulse to do something where you might otherwise think, that’s ridiculous. I shouldn’t do that. That makes no sense. But he goes and he feeds the bird despite the signs that say: “Do Not Feed The Geese.”

[music: “The House You Wake In” by Gautam Srikishan]

Death is an extraordinary leveler. Obviously, different people have different experiences of death. It might be that you’ve had an experience where somebody who was expected to die has died. And that’s different than a sudden, shocking death. It can also be that you have an experience of death where you deeply, deeply loved that person and had everything you had wanted to say, said to them. And other times there’s things unsaid, like is mentioned in this poem — “after the last words left unsaid between us.” Maybe he got a phone call saying his father was dying, and wanted to make it but couldn’t, because of the blizzard, and therefore there was farewells that he couldn’t say. Or maybe there was something that he had said that there was no apology for. Who knows? There’s all kinds of things that are held together here. This could’ve been an easy relationship or a difficult relationship.

And in the midst of all of that, he feels compelled to do something unexpected — to be brought by himself into a single moment in time, away from the “mosquito hum” of condolence. He’s solitary in this, just him and bread and birds, and then this magnificent goose. And I think there’s something in that, where he is seeking to level himself to the level of creatureliness. He wants to be a creature, feeding other creatures. He wants to have somebody else’s hunger — the hunger of a bird — that he can satisfy, maybe because there’s a hunger in him he doesn’t know how to satisfy. Maybe he wants to feel like there’s something he can do, something totally tangible. And this, I think, shows us how, in the wake of grief, often we are being called by our body into something very, very tangible.

[music: “Ashed to Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

Martín Espada is not a religious person, although when he writes about religion, he writes with extraordinary respect and insight. And you could argue, I suppose, that there is a certain Eucharistic idea of the feeding of the bread. I love, though, that he undoes that by the idea of feeding of bread, something Eucharistic, to this goose. And the goose is at once the god of geese and the demon of geese. And the goose is filled with its own fury and is selfish, almost, in getting rid of the other birds, the smaller birds all round him, and reaching with the sharp beak, the hard beak, and taking the bread. If this is a Eucharistic poem, it’s speaking about a Eucharist that totally satisfies profound hunger.

And I think you can see, perhaps, in this goose, his deep desire — not for Eucharist, but for something that will satisfy, in the wake of all of this, all of the things that grief brings: the sadnesses, the things unsaid that cannot now be said, and the mechanics, too — figuring out about organs, figuring out about what to do with the cremated remains, figuring out, what will the memorial service be?

All of those things are objects of order. And then you have this goose who is not an object of order at all, a goose entirely given to its own furious hunger. And in that way, I think, he might be taking a motif of Eucharist, but he’s completely doing some anarchy on it and showing us what the idea of the receiving of the bread of life might be, the kind of life that you need right now, in the midst of all the anger and anguish that grief brings.

[music: “Crem Valle” by Blue Dot Sessions]

The ten poems that Martín Espada writes about his father are gathered under the title “El Moriviví.” These are all in a book called Vivas to Those Who Have Failed.” And “El Moriviví,” one of the things it can mean is “he died,” but it can mean other things, too. And within it, it has words for a plant, and it has words for living and dying in it. And so, really, this is a sequence of poems about the living way that the living live with the death of somebody who lived in their life.

And in the midst of all of that, you have this final line that speaks about truce. And a truce is something that brings an end to some kind of hostility or fight or even war. And what is the truce? Is it the truce between the living and the dead? Is it the truce between a father and a son? Is it the truce between an adult parent and their adult children? Is it all of those things? Is it the truce between yourself and yourself, as well? So many of us find an enlivenment with the fury we carry in our lives. And that can be really invigorating, and also exhausting.

[music: “First Grief, First Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

The Blake quote in this poem as an epigraph is a quote from the book from the late 1700s by William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. And William Blake had written that book in a kind of a register sounding like scripture, almost like his own scriptures. There’s proverbs from hell in that book. And I think the quote that says everything is holy, coming from a book about the marriage of heaven and hell, makes us think of holding two things together that ordinarily aren’t held together. And here in this poem, we’re thinking of life and death being held together in a marriage, held together in the body of a son, in the life of a son and in the life of somebody who’s trying to think, how do I live now, with a dead father?

And until you get used to knowing how to live with a dead relative or a dead best friend, that’s always going to be something to learn anew, each time. It’ll be a strange marriage, in the stories you tell, the way that suddenly you have to find yourself using the past tense about somebody. And so I think describing everything that lives as holy is a way of saying that the desire to do this, even though you’re holding things together that feel like they shouldn’t be held together — life and death, or heaven and hell — that is done by the living, and that impulse is holy.

[music: “Memoriam” by Gautam Srikishan]

One of the things that I think this poem does is to alert us to paying attention to the intuitions we have, when we’re in shock or grief. Here he’s just come home from the memorial, and he decides, “I want to feed the birds.” And I wonder if somebody would’ve said, “That’s a silly thing to do now. You need to do the following,” or, “There’s these other things to do.” And even the signs that are there saying, do not feed the birds — “Do not feed the geese” — all of those objections that could get in the way of him doing this spontaneous thing that seems out of the ordinary, all of those objections are quietened. And I think the poem invites us to pay attention to when might we object to something somebody else in grief wants to do, something that seems strange, but they feel the urge, the desire to do it, And when in ourself, too, when we are in grief, might we feel some kind of impulse to do something that we can’t explain, but nonetheless, we feel we need to do — where would we object to ourselves in that?

And the poem invites us, I think, to say, follow that intuition. Go and do that thing. Pay attention to it — not because it has to mean anything huge, but because in the fight of time that death brings into our life, where time ceases for somebody’s voice as they live, or as they live in a particular way, pay attention to the time of the present. And it could be that that impulsive thing you wish to do is a way for you to reckon with time, as time has irrevocably changed for you now, in a time of grief.

[music: “Memoriam” by Gautam Srikishan]

“After The Goose That Rose Like The God of Geese” by Martín Espada. This poem has an epigraph — “Everything that lives is Holy” — from William Blake.

“After the phone call about my father far away,

after the next-day flight canceled by the blizzard,

after the last words left unsaid between us,

after the harvest of the organs at the morgue,

after the mortuary and cremation of the body,

after the box of ashes shipped to my door by mail,

after the memorial service for him in Brooklyn,

I said: I want to feed the birds, I want to feed bread

to the birds. I want to feed bread to the birds at the park.

After the walk around the pond and the war memorial,

after the signs at every step that read: Do Not Feed The Geese,

after the goose that rose from the water like the god of geese,

after the goose that shrieked like a demon from the hell of geese,

after the goose that scattered the creatures smaller than geese,

after the hard beak, the wild mouth taking bread from my hand,

there was quiet in my head, no cacophony of the dead

lost in the catacombs, no mosquito hum of condolences,

only the next offering of bread raised up in my open hand,

the bread warm on the table of my truce with the world.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Lily Percy: “After The Goose That Rose Like The God of Geese” comes from Martín Espada’s book Vivas to Those Who Have Failed: Poems. Thank you to Martín for giving us permission to use his poem. Read it on our website at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Chris Heagle, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, and me, Lily Percy.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions. This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land.

We also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me. Find those wherever you like to listen, or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.