Michael Pollan and Katherine May

The Future of Hope 4

Michael Pollan is one of our most revelatory explorers of the interaction between the human and natural worlds — especially the plants with which we have, as he says, co-evolved — from food to caffeine to psychedelics. In this episode of our series, The Future of Hope, Wintering’s Katherine May draws him out on the burgeoning human inquiry and science to which he’s now given himself over — the transformative applications of altered states for healing trauma and depression, for end-of-life care — and the thrilling matter of grasping what consciousness is for. This is an informative, intriguing, utterly uncategorizable conversation.

Image by Ifada Nisa, © All Rights Reserved.

Guests

Katherine May is an author of fiction and memoir, including: Wintering: The Power of Rest and Retreat in Difficult Times, The Electricity of Every Living Thing, and Burning Out. She is also the editor of an anthology of essays about motherhood, called The Best, Most Awful Job. Her podcast is The Wintering Sessions.

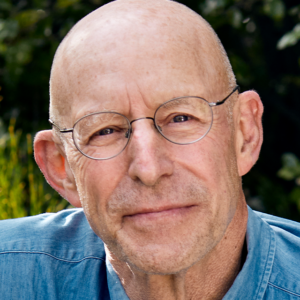

Michael Pollan is a professor at the University of California Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism. His many bestselling books include The Omnivore’s Dilemma, In Defense of Food, How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence, and most recently, This Is Your Mind on Plants. In 2020, he co-founded the UC Berkeley Center for the Science of Psychedelics.

Transcript

Transcription by Heather Wang

Krista Tippett, host: I like this description I found on Michael Pollan’s website, about the arc and the core of his body of work: “For more than thirty years, Michael Pollan has been writing books and articles about the places where the human and natural worlds intersect: on our plates, in our farms and gardens, and in our minds.” He has undeniably changed the culture of food, and more recently, he opened wide a new kind of cultural dialogue, with his book How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence. And his newest book, This Is Your Mind on Plants, delves into the ordinary ways in which we have integrated a relationship with mind-altering plants — caffeine being Exhibit A — into our basic lives and our social functioning.

And Michael Pollan is the person Katherine May immediately proposed she’d like to draw out in conversation for our series The Future of Hope. You may know her from her gorgeous book and her On Being episode on “wintering”: “wintering” as a season in the natural world and a recurrent season in every human life. She, too, operates out of a deep curiosity about the human mind, the remarkable complexity of mental states and well-being, informed in part by her own welcome, mid-life diagnosis of autism and her love of cold-water swimming. She finds hope for our common future in the world of human inquiry and science to which Michael Pollan is contributing so richly — the healing potentials of altered states — with transformative applications, for trauma and depression and end-of-life care, and for the thrilling matter of grasping what consciousness is and is for.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. I am delighted to plunge you now into the rich, informative, moving, utterly uncategorizable conversation between Michael Pollan and Katherine May.

Katherine May: So thank you so much for agreeing to talk to me. I don’t know how much you know about these conversations, or whether it’s something you’ve just dived into.

Michael Pollan: I don’t know that much. I know a little bit about you, and I know Krista, and I’ve listened to her show on and off for years, but I was very excited at the prospect of doing this with you.

May: Well, I got asked who I’d like to speak to, and I think people were a little surprised at my choice, because I think they were expecting maybe a writer a little bit more like me. But I — I mean, I loved How to Change Your Mind. And I wanted to talk to you because I think there’s surprising crossover in our work in lots of ways. I think we’re both thinking about the kind of edges of science and spirituality, and where they meet and where they don’t meet. I think we’re both thinking about the spaces that healing happens in, and change, and transition. And I think we’re both interested in the natural world, in a funny kind of a way. We’re both thinking about altered states in a different way and how, as quite secular people, we come to terms with those big moments of change.

But I wanted to start by asking you about plants and your fascination with them, because it seems to me that that’s the kind of ground from which everything grows, for you. And I wondered, just to begin with, whether you grew up with gardeners or gardening. Where did it come from?

Pollan: It did. I mean, I think all my work does flow out of my interest in plants and gardening; it was the topic of my first book, Second Nature — but it goes way back. I had a vegetable garden when I was eight years old. We were living in suburban Long Island, in a town called Woodbury. And I had a grandfather, my maternal grandfather, who was a passionate gardener — vegetables. Only things that had obvious value would he grow. He was also quite the materialist and a successful businessman. But he started out — he was an immigrant from Russia, who came over in 1916 or ’17 and started out very poor, selling baked potatoes from a cart on Long Island, and then moved into the produce business, and then moved into real estate as farming in Long Island gave way to shopping centers and subdivisions. And he was part of that translation process.

But I loved his garden. And he had a big vegetable garden on the South Shore of Long Island. And some of my best memories as a child was being in his garden at harvest time. And just the miracle of finding ripe vegetables on the vine and picking them, and the idea that nature could produce these things that were so delicious and so valuable to us was something that I was taken with from a very young age. So in imitation of Max, my grandfather, I planted my own vegetable garden — although I called it a farm. And indeed I would, whenever I could put together five or six strawberries or green beans, put them in a Dixie cup and sell them to my mother, and she would give me a nickel or something like that; so it was a business. [laughs]

May: I love that you did that. [laughs]

Pollan: And I just got great pleasure from the whole process of planting and the miracle of seeds turning into plants, turning into things you could actually eat. I had no interest in flowers at the time. They seemed useless. [laughs]

May: Do you grow flowers now?

Pollan: I do. I grow all kinds of things now. But — I still grow vegetables, though. It’s still my first passion. So yeah, it goes way back. It fell away for a while. There’s a period in life — and I see this in my students, too — in adolescence, early adulthood, where your connection to nature is kind of attenuated.

But anyway, I came back to it in my late 20s. And we bought this place where I am now, in northwest Connecticut. It was a kind of rundown, 5-acre sliver of somebody’s dairy farm. And I started gardening really seriously there, and put in raised beds, and found this stash of composted cow manure behind the barn that made my garden thrive for the first few years —

May: Well, that’s handy. [laughs]

Pollan: It was, very handy — and just got into this engagement with plants and thinking about what they had to teach us and how they worked for us and, also, how we work for them.

May: So let’s talk a little bit about that, because, I mean, you think that there’s a very special relationship between humans and plants, right, and that we’ve coevolved.

Pollan: In the case of the domesticated plants. And there was a particular moment, there was kind of an epiphany I had in the garden that I wrote about in The Botany of Desire, where I was planting potatoes in my garden, seed potatoes, and it was that week in May where I had a bunch of apple trees, very old apple trees in my garden that were just absolutely buzzing, alive with the attention of bees — I mean, just vibrating. And I, you know, one of the things I really like about gardening is it doesn’t consume all your mental attention; you can actually think about something else while you’re gardening. I love that about it. I’ve done woodworking and construction, too, and you can’t do that; only at great risk to yourself can you let your mind wander when you’re cutting boards. But gardening, you’re unlikely to really hurt yourself.

And I was watching these bees work on this apple tree, and it occurred to me that I’m not so unlike these bees as I would’ve thought, in that they think they’re getting the best of this relationship with the tree, that they’re robbing it of nectar, breaking in and stealing. And they have no idea that the tree has manipulated them to pay it a visit, that the tree is busy powdering them with pollen on their legs without them being aware of it, and that the tree is using them to spread their genes around the neighborhood or around the world. And how different was that for me? I had ordered these seed potatoes from across the country, from Oregon, and I was spreading their genes, and I thought I was in charge. And so it gave me — it was a kind of humbling realization.

May: It’s like we’re doing the bidding of the plant overlords. [laughs]

Pollan: Exactly. And we are. So it just gave me this enhanced respect for the cleverness of plants and other domesticated species and a real sense of, we’re in this together.

May: Actually, that makes a nice link to caffeine, which is one of the plant substances you’ve written about recently, in This Is Your Mind on Plants. There’s this sense that you bring across that we’re not only intertwined with plants on an evolutionary basis, but we’re quite dependent on the chemicals they produce and on the altered states they produce. And the way you write about caffeine suggests that actually, we are constantly in this altered state that’s brought about by a plant, that isn’t intrinsic to our humanity. I found that fascinating. Can you talk about that a little?

Pollan: Yeah, I found it fascinating and kind of shocking that what many of us now regard as normal, everyday consciousness is actually a form of consciousness that has been altered by our daily ingestion of caffeine. And the way to figure this out is simply by giving it up, which I did. I had a three-month caffeine fast.

I’ve been drinking caffeine since I was 10, more or less. I got a really early start. And I was told it would stunt my growth and things like that, but in fact, I got to be 6’1” or 6’2”, so if it did, you know, that’s fine. But when I was off caffeine — and I’m not just talking about the first few days, which were a torture, but even weeks later, I didn’t feel myself. And I thought, how astonishing is that, that my self is a caffeinated self? The self I recognize, the skin I felt comfortable in, was someone who had had a cup of coffee and a couple cups of tea over the course of the day, and that the texture of consciousness had been inflected by that. And I think that’s true for many of us. I mean, 90 percent of people, adults on the planet, have a daily relationship with caffeine in some form or other, which is quite astonishing. I don’t know of another drug like that.

May: That we’re so knitted together with, yeah.

Pollan: We are. And of course, this has been a great strategy for the coffee and tea plant, pretty obscure plants in obscure parts of the world that now circumnavigate the world. But for us, it’s been, I think — I mean, you can argue it both ways, but I think it’s been a blessing in many ways. It’s given us many things that we value. Now, you could argue that it was a negative innovation, to have a population essentially addicted to caffeine, in that it disconnected us from nature. You know, we used to kind of go to sleep soon after it got dark, wake up when it got light — we were tied to the rhythms of nature more tightly, and caffeine freed us from those rhythms, allowed us to kind of colonize the night to a much greater extent than we had. And you would not have a late shift or an overnight shift without caffeine. So it distanced us from nature, but I also think it gave us a lot of things we take for granted and value.

May: Well, it’s so interesting to talk about that in the context of another substance you write about, which is opium, which obviously is addictive in a very different way to coffee and is — I mean, I think probably both our countries, but yours more than mine — causing a huge crisis …

Pollan: Tremendous problem.

May: … ongoing crisis at the moment. I’d love to know what you think about that, because actually, the way you write about opium, it’s actually quite benign in its natural form. What’s the challenge here? What’s the difference between the opium that you might grow in a poppy in your garden and the opioids that are causing so much trouble?

Pollan: Well, there are a lot of differences. I mean, in general, there are many drugs that in their sort of natural plant form are fairly benign. I mean, you can get addicted to poppy tea that you grow in your garden; that can happen. But it’s quite a mild experience. It’s not as hard to give up as people think. And there’s something protective, I think, in using drugs in that form. I mean, cocaine is another great example. People in South America, in Bolivia and Peru, chew coca leaves all day long; it’s kind of their caffeine, and it’s not a problem. It’s routine. But when you refine it and intensify it and remove whatever other — you know, there are these suites of alkaloids in these plants; it’s not usually one, but there are other things in coca or in opium. And when you purify it, you create something novel that is much more dangerous and much more addictive. So that’s something to — so the white-powder drugs are more dangerous than their plant sources, in general.

May: A little like sugar.

Pollan: Yeah, in a way, much like sugar. When we take sugar in from fruit, even though it’s the same thing as refined sugar, it’s coming with all these other vitamins and nutrients and fiber, and it’s absorbed more slowly, and it’s not as bad for us as refined sugar. So that’s part of it.

But you know, drugs are a very mixed bag. I mean, I’m — you know, I’ve written positively about them, but I’m acutely aware of the fact that they can be a scourge, too, and we see that all around us. I think the Greeks had a more subtle understanding of drugs: we tend to either celebrate them or condemn them; they called them “pharmakon,” and a “pharmakon” could be either a blessing or a curse, a poison or a medicine. And whether it’s one or the other doesn’t depend on the drug so much as the context in which it’s used and the reasons for which it’s used. The drugs aren’t inherently good or evil; it’s very contextual. And that’s a subtle idea.

May: It’s about set and setting. [laughs]

Pollan: It is. Well, set and setting definitely affects all drugs. It’s not just a — that term was coined by Timothy Leary to talk about psychedelics, but in fact, it’s true of opiates; it’s true of anything.

May: It’s very tragic. It sort of speaks to our humanity, that the thing that we reach for in the most distress we might have ever been in — in severe pain, in severe anguish — can become the thing that ultimately shortens or ends our lives. And it seems to speak to something about what it is to be human, that there are no easy solutions to anything in this world, and everything is a kind of complex set of knock-on effects.

Pollan: Drugs are an excellent example or metaphor for that very idea because, I mean, opiates are a blessing, too. I mean, surgery would be unbearable without them. But at the same time, it causes us or forces us to hold two contradictory ideas in our head, which, of course, we’re never very good at. But that is definitely one of the lessons of what I’ve learned.

[music: “Borough” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, Katherine May in conversation with Michael Pollan, for our series The Future of Hope.

[music: “Borough” by Blue Dot Sessions]

May: I was so interested, as I said, when I read How to Change Your Mind. And I’ll — shall I read out the whole subtitle, because it’s so — it’s the longest subtitle I’ve ever read in my life. [laughs]

Pollan: It’s long, I’m sorry, but yes [laughs] …

May: I’m going to read it.

Pollan: … because I don’t even know it by heart.

May: [laughs] So I could just sneak some extra words in there, and you’d never know.

Pollan: [laughs] You’re right.

May: How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression, and Transcendence. That’s quite the subtitle. [laughs] I love it.

But one of the reasons why it genuinely changed my mind was because I’m a child of the ’80s and ’90s; I grew up with the war on drugs, with “Just Say No,” but also with the kind of moral panic around acid house in the early ’90s, specifically. So I knew psychedelics as these dangerous drugs that would send you mad. That is exactly what I’d been told about it when I was like 10 or 11, and reading your book, I realized I’d kind of carried that uncritically into adulthood, if I’m completely honest. And I’d come across friends who’d had psychedelic experiences, but part of my aversion was that I found their stories really boring. Like, there’s something about people that have taken a lot of acid, that they will tell you incessantly about it. And I thought, well, one of my motivations is I just don’t want to become one of those people that’s like, saying, “I saw a lizard on my hand, and my friend saw it, too,” or whatever it is that they go on about. [laughs]

Pollan: [laughs] Fair enough.

May: But actually, one of the things you point out is that those experiences are so significant that people can’t help but talk about them, I think.

Pollan: Yeah. I mean, describing psychedelic experience is a little like describing your dreams.

May: Never interesting. [laughs]

Pollan: You’re apt to bore people to tears, but they’re resonant with meaning for you. And many psychedelic experiences, the insights people gain are really banal. And I struggle with that, writing about them.

So there’s a chapter, as you know, in the book where I go through various experiences I had with psychedelics. Like you, I, even though I’m older than you are, I grew up — I came of age a little too late for the psychedelic ’60s, and by the time I would even consider the idea of using a psychedelic, we were hearing the horror stories. People were jumping off of buildings. People were taking trips from which they never returned, ending up in psych wards. And this is what you heard. And I did not use them, as a young person. I was terrified. I just didn’t think I was psychologically sturdy enough, too, to withstand the storm that it represented to me, to take LSD or psilocybin. So I was really a late bloomer when it came to psychedelics. I didn’t have a serious experience till I was in my late 50s, for exactly those same reasons. And I, too, was kind of bored by what I heard when people were describing their trips.

But, as someone who now has described those experiences — and I work very hard to figure out a way to write about them that wouldn’t be boring — it’s this mix of — I mean, you do have banal insights. I mean, the classic one, of course, is that love is the most important thing in the universe. And, you know, that could be on a Hallmark card, but it’s also profound, and the line between banality and profundity is actually quite fine. Things are banal because we’ve said them too many times; things are banal because — and we’ve hollowed them out through repetition. But there’s still a kernel of truth to a lot of banalities, as there are to clichés. And one of the things that happens on psychedelics is that you experience those banal ideas with the full force of their original meaning.

And to recover that profundity is an amazing experience. And it is a reminder that we spend a lot of time encrusting these fundamental ideas about life and reality with irony and all these protective rhetorical devices to keep them at bay. And suddenly, all that crust comes off, and like, oh my God, love is the most important thing in the universe. And you understand that, and you have a conviction about it that is just unshakeable.

I mean, one of the most striking things about psychedelic experience, to me, is something William James isolated more than 100 years ago. And he said that — he was speaking of mystical experience in general, and a powerful psychedelic experience is a mystical experience in various ways. And he said that one of the characteristics of that, besides ego dissolution and transcendence of space and time, is what he called the “noetic quality.” And this was the quality that what you learned, the insights you had, were not merely opinions but were revealed truths. And they have a stickiness and a power that I think is central to the experience, and it is what allows people to change.

May: It’s a different kind of knowing. It’s like the difference between knowing and knowing.

Pollan: And knowing in your head, and knowing in your heart and in your whole — with your whole being. It is a different kind of knowing. And it’s hard to evaluate that knowing; I mean, people also emerge from experiences with the sense of an afterlife, especially the cancer patients who’ve had guided psilocybin journeys. Many of them say, yes, I saw the great plain of consciousness that awaits me when I die. And they’re absolutely sure about it, and it makes it easier for them to die.

We don’t know. We don’t know. You know, it seems to them a revealed truth. Is it a truth? There’s no way to judge. And you can take a very pragmatist view — it’s like, well, it doesn’t matter; we don’t know what happens after you die, and if people come to that belief, it’s not like we’re inducing that belief in them. It’s — the drug doesn’t contain that belief, it’s just a molecule. It came out of their own minds. And so anyway, there are all sorts of epistemological questions that arise.

May: But I think before we talk too much about those, I think probably, still, there’ll be listeners here who are still kind of in that ’80s, ’90s space of saying, But is this dangerous? Like, at what risk does this come?

Pollan: Yeah, we should talk about risk.

May: We should talk about that, because actually …

Pollan: I think it’s really important.

May: … you make a case to say that they’re not actually terribly risky, and almost anti-addictive.

Pollan: So, speaking of the so-called “classic” psychedelics, things like psilocybin, which comes from magic mushrooms, or LSD or DMT or ayahuasca — I mean, these are kind of classic psychedelics — I did a lot of research. I was 59, 58 when I was going to start on them, and I was not that, you know, 20-year-old with no developed sense of judgment and understanding of risk. So I did do my due diligence, and I was very surprised by what I found. The first was that there is no lethal dose, no known lethal dose of the classical psychedelics. That’s astonishing. I mean, there are many drugs in your medicine cabinet that you bought over the counter, things like acetaminophen, that do have a lethal dose, and it’s only like 20 pills. So you can’t overdose. You could have a terrifying experience on a high dose, but it’s not going to kill you. That’s one astonishing fact. The other is that they’re not addictive. They’re not habit-forming.

So: not habit-forming, not lethal; so what are the risks? The risks are psychological, and they’re real. People can have so-called “bad trips,” really frightening experiences that go on and on and on. In some rare cases, people have had psychotic breaks that did put them in the hospital. And people with various forms of serious mental illness are disqualified from the studies going on right now, because of concerns if they have any kind of risk for schizophrenia or personality disorder. So there are risks; they’re mitigated to a large extent, if you are administered psychedelics in a proper setting, with guidance — in other words, a sitter of some kind, who is there with you, who can reassure you, who can prepare you for the experience and divert you when you get into a really scary place. But people do stupid things. They take psychedelics in, you know, walking down the street in Manhattan. Encountering strangers or weird things on psychedelics, it amplifies the whole experience in a way that can be truly terrifying. So that’s kind of where I, you know — that was very reassuring to me, on the whole, that this was something that, if I worked with a guide, which I did, and paid attention to set and setting, that was a risk well worth taking. And indeed, it turned out to be.

May: So what is that setting? It’s more than just, like, the room it’s in, isn’t it. It seemed to me that the people you worked with took care of a kind of ritual entry into the process; even if that was secular, that they found a way to invite you slowly in, in a very kind of conscious way.

Pollan: Yeah, there is a ceremonial aspect to it, which I think is very interesting. I mean, if you look at how traditional cultures have used psychedelics, they always do them in a ritual context. And there is some inherently protective thing about ritual. I think this applies even to the use of alcohol, and possibly to tobacco. The people who use these things in a ritual way are much less likely to get in trouble. And there’s something comforting about ritual.

And they also prepare you. You get what some call a set of flight instructions, before you go, and that’s really helpful, too. And surrender, I think, is probably the most important piece of advice that they will give you in advance, because it is when you’re resisting what’s happening that you get anxious and frightened, because what might be happening is your ego may be just melting. Your sense of self may be dying. And if you fight that and try to hold on for dear life to your sense of self, that fight is going to create a lot of anxiety.

May: And this is that experience of ego dissolution — the idea that you lose your sense of yourself as an individuated person and become merged with —

Pollan: Something larger. People do have the sense of merging into the universe or with divinity or with other people — and that’s an ecstatic experience. It’s so rare. We’re so isolated in these skins of ours. And to let that go and be a part of something large is — I mean, that’s the essence of the mystical experience that James talks about. And that was wonderful. It wasn’t happy, necessarily — in my case there was something sad about it — but it just felt so right and so beautiful.

May: There was kind of a melancholia about the whole — because you found yourself feeling very connected with members of your family, both people who had passed and people who are alive now, I think. There was that real merging with the significant people in your world.

Pollan: Yeah, specifically my grandfather, who I had a wonderful relationship with — this is the paternal side grandfather. And I looked in the mirror at one point, which is always a risky thing to do on psychedelics, and I saw him, not me, and I felt connected to him in a way I never had before. And he’s been dead for 15 years, I guess. And, you know, it wasn’t a particularly powerful relationship; it was a very nice relationship; he was a very sweet man; he did not have a mean bone in his body, and very old-fashioned in many ways. But it was that sense of connection.

I mean, for me, that has been the great sort of spiritual takeaway of psychedelics. I’m a very secular person. My belief system is more materialist, in the philosophical sense, than not, and I had always assumed, when I heard about spirituality, that it implied a belief in the supernatural and that you had to believe in God, or you had to believe in angels or some beyond, some other realm unseen to us, unmeasurable by science. And that never seemed right to me.

And then I had these powerful experiences that I could only describe as spiritual, yet they weren’t metaphysical in any way. They were simply about connection, powerful connection. And in one of my experiences, unguided, with psilocybin, I felt that connection with the plants in my garden, to go full circle.

May: Unsurprisingly for you, yeah. [laughs]

Pollan: Unsurprisingly, for me. And I had had — you know, we talked earlier about this idea that we’re in this symbiotic relationship with these plants, which is a pretty heady idea; it’s an intellectual idea; it’s based on coevolution and Darwin. But that idea became felt, became flesh, on this experience. That sense of alienation that we all feel, to some extent — when I say “all,” I mean those of us living in the industrialized West; it may not be true for some Indigenous peoples — it went away. And there was a noetic quality to it, too. I felt, this is more real than what I normally feel. So I was faced with the fact that I’d had a spiritual experience, but it was grounded in what we know to be true, which is to say, we’re all part of an ecosystem.

May: It’s that deeply meaningful mundane again, almost, isn’t it. We know we’re part of nature, but we don’t know we’re part of nature until we really experience it.

Pollan: But we don’t deeply know. We don’t believe it. At some fundamental way, we don’t believe it. Otherwise we would be confronting climate change in a way we weren’t, or we wouldn’t be fantasizing about going to other planets, which seems to be becoming increasingly popular fantasy. Yeah.

So it was — so spirituality — so I realized the opposite of spiritual was not material. The opposite of spiritual was egotistical thinking; that it was the ego that separates us, whether it’s from nature — it’s the ego that allows us to objectify the other. And that other might be the natural world, but it could also be other people; many of us objectify other people. And so that became how I came to understand spiritual experience. It’s deep connection. And it might be with God, for some people, but for me, it’s with nature. It’s with music. It’s with all these things that I merged with when this barrier came down.

[music: “The Posture of a Melting Snowman” by Lullatone]

Tippett: After a short break, more with Michael Pollan and Katherine May.

[music: “The Posture of a Melting Snowman” by Lullatone]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, Wintering author Katherine May is drawing out Michael Pollan, a singular voice at the intersection of the human and natural worlds, especially the plants with which we have co-evolved and intersect with on our plates, in our farms and gardens, and in our minds. These two have been speaking about his most recent focus, which gives Katherine hope for our common future: how Western culture’s troubled history with plants with mind-altering effects is now also giving way to transformative, healing applications for trauma, depression, and our very grasp of human consciousness.

May: As I said at the beginning, I think you and I are very similar in this, in that we both write in a kind of spiritual realm, but we’re both deeply secular. And it is uncomfortable. And I think one of the things that makes us both self-conscious about it is knowing what our peers would think of this kind of talk, as well, and there’s not permission given to expand on this kind of thinking and this almost animistic sense of the world that you get when you delve — I mean, because I get a very similar sense, because of being a long-term meditator. Like, that’s given me that very similar impression of interconnectedness and of fluidity between different living things. It’s not — I don’t feel separate, and that seems self-evident to me.

Pollan: I talked to one psychiatrist who studies meditation, and he thought that there might be a point where we’d use psychedelics to begin a meditation practice, because psychedelics are not a practice; you can’t use them every day. You don’t want to use them every day. But meditation is, and so I think there a lot of links. And in fact, at the neuroscientific level there are a lot of links, that similar brain networks are quieted during meditation and psychedelic experience. So it isn’t surprising.

May: It looks very similar.

Pollan: And you talked earlier about the, you know, science and spirituality and where those two, you know, we think of them in conflict, but in fact, one of the interesting things about psychedelic research is it’s giving scientists an opportunity to study spiritual experience. Spiritual experience is a human phenomenon. We are wired for mystical experience. And it can be kicked off through psychedelics, through meditation, through fasting, through sensory deprivation, isolation, vision quests — so what is that about? And it has certain patterns in the brain that we’re beginning to identify. So I see science making these tentative steps into understanding spirituality, and I think that’s very exciting work.

May: And I’m particularly interested in the way that — again, probably counter to our expectation, in your book psychedelics emerge as an experience that should be sought in the second half of life, as an older person who can maybe process the experience or maybe who’s less likely to use it as a party drug, but also in terms of processing serious illness, mortality, end of life — all of those, I don’t know, all of those kind of common rites of passage that maybe we’ve lost a ritual experience around, as time’s progressed.

Pollan: Yeah — I mean, I think part of the interest in psychedelics has to do with a religious impulse that people have and is not being satisfied by religion. You definitely have a lot of people who are secular, seeking spiritual experience this way. And that is more urgent, the older you get, when you start thinking about mortality.

But the other benefit that I think psychedelics offer people as they age is — well, there’s a couple benefits. But one is, we are more deeply mired in the grooves of habit, the older we get. We have developed a set of very sophisticated algorithms to get us through the day, get us through arguments with our partners, get us through how we do our work — it all becomes kind of habitual, and very efficient for that reason, but habit, you know, dulls us to reality. You know, there’s a trade-off. Again, it’s keeping two ideas in your head. Habit helps you get stuff done, but habit cuts you off from experience, fresh experience, seeing things freshly. So there’s the throwaway line in How to Change Your Mind that maybe psychedelics are wasted on the young. There is — I mean, I know lots of young people who’ve had very powerful and valuable experiences. But I think they have a unique benefit to people as we get older and as we’re thinking about death, as we’re thinking about these spiritual questions, but also as we’re set in our ways and losing contact with experience, as a result. There’s a kind of cleaning the doors of perception that’s going on.

And there’s a wonderful metaphor that one of the neuroscientists gave me. He was a Dutch neuroscientist working in London. And he said, Think of the mind as a snow-covered hill and your thoughts as sleds going down that hill. Over time, the more runs of the sled, the deeper the grooves, and it becomes very hard to go down the hill without getting drawn into the grooves. They become attractors. Think of psychedelic experience as a fresh snowfall that fills all the grooves and allows you once again to go down the hill, along another route, any route you want.

I thought that was a beautiful metaphor.

May: That’s lovely.

So I’m conscious, as we speak, that we do so in relative safety, that we’re able to talk about what remain controlled substances as two kind of middle-class white people who can, you know, shoot the breeze about this, and that this wouldn’t be a safe conversation for every community, that other people do not feel like they can talk about drug experiences in any kind of openness, and that there’s a certain amount of privilege that surrounds the people who can buy psychedelic therapies, even if it’s kind of underground at the moment. I just wanted to sort of touch briefly on the problems with this right now, because I, you know, I think it’s really important not to exclude them. Not everyone can have access to this, and what happens if this becomes more commodified?

Pollan: Those are great questions. And the psychedelic world is very white and very privileged. I think one of the reasons has to do with the nature of the drug war, and the drug war has targeted people of color. If you go back to Nixon, he allegedly said exactly that, that the reason they wanted to ban a certain class of drugs, which they did in 1970, was because they were going after their two enemies, who were “Blacks and hippies,” as he put it. And if they made these drugs used by those communities illegal, they could harass those communities — come in, discredit them, do all sorts of things. It was not about public health at that point, it was about political power.

For African Americans, being involved with drugs carries special risks. They’re much more likely to be prosecuted. You know, we talked a lot about set and setting. You have to feel very safe before you give your mind over to a psychedelic experience, which is essentially going to incapacitate you for six hours or 12 hours. And if you feel like you are under attack or live in a threatened environment in any way, it’s probably dangerous to do psychedelics under those circumstances. So I think that that’s part of it, also.

But, on the other hand, we are seeing that these substances can be used to treat trauma very effectively. And racial trauma is a tremendous problem, in the U.S. and in the UK. So actually, there is — there may be value for these communities in particular, from psychedelic therapy. And there are people in the United States pursuing this right now. And that’s very encouraging.

It’s true that underground therapy is expensive, more expensive than it should be, because demand exceeds supply and there’s a lot of profiteering going on, I think, which is really unfortunate. But the value of bringing these substances through the normal drug approval process is if they prove themselves as effective treatments for trauma and depression and addiction and anxiety, they will become more available. They will become, eventually, covered by insurance, perhaps even by Medicare and Medicaid. And that’s the best way to democratize them. And that’s why I think that’s really important work.

There are limitations to making them strictly medical, and I think that they have value to people who don’t have diagnoses of trauma or depression or addiction, and we need to find a way to make it accessible for those people, as well. But getting them approved as drugs will remove the danger of using them, for certain communities, and will improve the access. At least, that’s my hope.

May: Yeah, and that’s a — and it’s also interesting to think how some of the most insightful existing uses that we have for psychedelics come from Indigenous communities and from longstanding practice. And yet, White western use seems to threaten those traditions. I mean, it’s fascinating to talk about this, and it captures an imperfect point in time, where we’re rediscovering science that we abandoned half a century ago and we’re maybe coming to terms with new meanings that we wouldn’t have seen at the time — that we should have seen, but that maybe we wouldn’t have seen. And maybe we’re processing this in a very 21st-century way and thinking much more about the intersectionality of the experience.

We need to end. But I want to ask you a final question and really to take it back to you, because I’d love to know how you’ve been changed by this and what this means to you on an ongoing basis.

Pollan: For myself, it has opened up all sorts of questions that I’m thinking about and working on. I mean, it’s hard to take psychedelics and not wonder about consciousness, this miracle going on in our heads, and what is it and how does it work. This issue of connection, and rethinking that, and feeling a closer bond with nature, with the plants in my garden, that’s been a real legacy of it.

Also, you know, I said at the beginning that I was this confirmed materialist. And I have a lot more questions, too, about consciousness, ideas that might have struck me as absurd. One of the convictions you leave psychedelics with is that consciousness may exist outside of our heads. Is that true? I mean, so it’s led to a whole parade of new questions, and in that sense, it’s shaken up my worldview in a way that I think it needed to be shaken up. It was too confident. I was such a believer in scientism. So it’s added to the amount of doubt I had, rather than certainty, but that’s OK. For a writer, it’s actually a good thing.

May: Seeking’s the thing. [laughs]

Pollan: Yeah. So, and if you ask my wife, she would say that it’s made me certainly more open than I was in some ways, more emotionally available, happier to talk about emotional issues. It’s been very meaningful in our relationship, too, in terms of deepening the kinds of conversations we have and sharing things. You know, it’s not something that is a regular part of my life, but it is an occasional part of my life, and I’m so grateful to have discovered this means of self-exploration and world exploration that I had been dismissive of. And so I’ve learned a lot. Have I been transformed? I don’t feel like I’ve been transformed, but I do feel like I’ve been opened up.

May: And that’s a great thing in itself, I think. [laughs]

Pollan: Without question. Without question.

May: That cracking open of the kind of hard shell that we carry around — yeah, it’s a gift.

Pollan: Yeah, in your 60s? I’m 66 now, and this doesn’t usually happen. People are — the shell is getting harder and tighter. And to crack it now is, I think, is a great privilege.

May: And very finally, what hope would you leave us with, for the future of this human technology, or this spiritual tool, whichever way we see it? Where would you like to see this going?

Pollan: Well, my fondest hope would be that — the psychedelic renaissance has come along at a moment where we most need it, at a moment where we’re learning that the objectification of nature, the objectification of other people that egotistical thinking leads to, is leading us to disaster — I’m talking about the environmental crisis; I’m talking about tribalism. And we don’t know the answer to this question yet, but do psychedelics have the potential to help us address those two problems, by softening ego thinking? I don’t know that that’s true; it’s certainly a conviction you emerge from the experience with, but we have to research whether that’s actually true. But my fondest hope is that this medicine has arrived at a moment when we’re really sick, [laughs] and it might help treat us, because we’re at a —

May: And it brings the potential of healing on a mass scale.

Pollan: On a massive scale. And there’s so many questions as to how you might think to administer a drug to an entire population. And that’s not — I’m not talking about putting it in the water supply. But to the extent it can produce this softening of egos and increase in openness — God, what do we need more?

May: Michael, thank you so much. It’s been wonderful to talk.

Pollan: Thank you, Katherine. A pleasure.

[music: “Walk in the Sky” by Bonobo]

Tippett: Michael Pollan’s latest bestselling book is This Is Your Mind on Plants. In 2020, he co-founded the UC Berkeley Center for the Science of Psychedelics.

Katherine May’s books of fiction and memoir include Wintering: The Power of Rest and Retreat in Difficult Times.

You can find my conversation with Katherine, “How Wintering Replenishes,” at onbeing.org or in your podcast feed.

[music: “Walk in the Sky” by Bonobo]

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Laurén Drommerhausen, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Jhaleh Akhavan, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Ben Katt, Gautam Srikishan, Lillie Benowitz, April Adamson, Ashley Her, Matt Martinez, and Amy Chatelaine.

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear, singing at the end of our show, is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent, nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org;

Kalliopeia Foundation, dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality, supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org;

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives;

The Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education;

And the Ford Foundation, working to strengthen democratic values, reduce poverty and injustice, promote international cooperation, and advance human achievement worldwide.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.