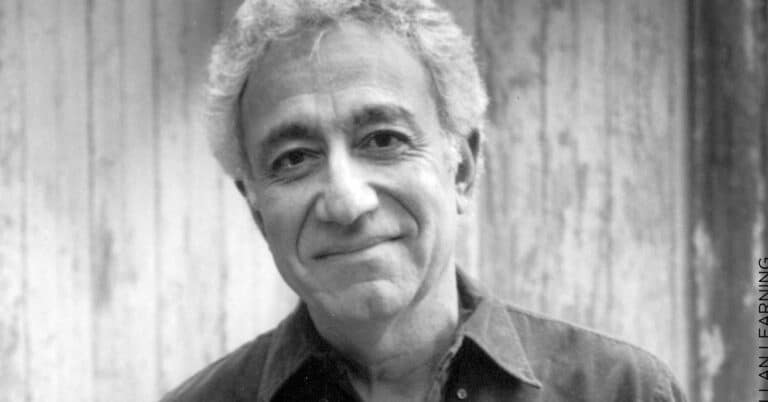

Mike Rose

The Deepest Meanings of Intelligence and Vocation

“I grew up a witness,” Mike Rose wrote, “to the intelligence of the waitress in motion, the reflective welder, the strategy of the guy on the assembly line. This then is something I know: the thought it takes to do physical work.” Mike Rose died in August, yet the particular way he saw the world resonates more than ever before as our debates about the future of school and work only intensify. He argued with care and eloquence that we risk too narrow a view of the way the physical, the human, and the cognitive blend in all kinds of learning and in all kinds of labor. Mike Rose’s intelligence would enlarge our civic imagination on big subjects at the heart of who we are — schooling, social class, and the deepest meaning of vocation.

Image by Courtesy of UCLA/UCLA, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Mike Rose was a research professor in the UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies. He authored several books, including The Mind at Work: Valuing the Intelligence of the American Worker, Why School?: Reclaiming Education for All of Us, and more recently Back to School: Why Everyone Deserves a Second Chance at Education.

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: Mike Rose once wrote this: “I grew up a witness to the intelligence of the waitress in motion, the reflective welder, the strategy of the guy on the assembly line. This, then, is something I know: the thought it takes to do physical work.” Mike Rose died after a short illness, in August. Yet the particular way he saw the world resonates more than ever before, as our debates about standardized testing, the information economy, and the future of school only intensify. He argued with care and eloquence that we risk too narrow a view of the way the physical, the human, and the cognitive blend in all kinds of learning and in all kinds of labor. His insights from our 2010 conversation, a conversation I cherished, offer much to enlarge our civic imagination on big subjects that are newly alive about the heart of who we are, including class dynamics we still scarcely know how to speak about in U.S. culture, and the deepest meanings of intelligence and of vocation.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

Mike Rose: You and I both know people who are doing work that the culture at large, from a distance, would say is really meaningful, and they’re miserable. They’re as unhappy as can be. You know, the miserable lawyer, the unhappy neurosurgeon, right? Meaningfulness is a more fluid and rich and variable concept, I think, than we tend to imagine.

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

Mike Rose was a professor in the UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies. He authored several books, including The Mind at Work and Back to School: Why Everyone Deserves a Second Chance at Education. He grew up in Pennsylvania among Italian immigrants. His father was chronically ill, and his mother supported their family as a waitress.

How would you start to tell the story of how and when you became attentive to what you would call the “spirit of education” — maybe you wouldn’t have called it that then, but what you now think of as the essence of education?

Rose: Right. That’s a lovely question. And you’re right, I wouldn’t have talked about it that way at the time. I’ve got to say that it began, for me, in my senior year in high school. You know, I didn’t do so well in school. I could read, which was really fortunate, since that’s the sort of meta tool. o I could read, and that was immensely helpful, but I was horrible in mathematics; I couldn’t diagram a sentence if you held a gun to my head. I just didn’t do that well in school.

And so then when I went to high school, I ended up in the vocational track. Those were the days when schools were pretty rigidly tracked, right? And then a remarkable thing happened. Somebody found out that somewhere along the line, my entrance tests to high school got confused with somebody else whose last name was Rose. And so, suddenly, in my junior year, I find myself in this college preparatory track. And I was as ill-prepared for that as I was for playing the defensive tackle on the football team, you know? I was so in the deep end of the pool.

And so I drifted through all that, and in my senior year had the sheer dumb good luck of getting an English teacher who himself had just left Columbia University and came out west and wanted to teach for a few years.

Tippett: And that was Jack McFarland, right?

Rose: And that was Jack McFarland. And so, suddenly, after all those years of sort of drifting around and not knowing what was up, we hit this guy who is giving us, every other week, a new book to read, starting with Homer and working his way down to Hemingway. And for some reason, some complex set of reasons, it caught my fancy. The guy just caught me. And so when you ask me the question about when did I begin to think about, or understand in some kind of way this spirit of education, it had to be there.

Again, I certainly wouldn’t have expressed it like that, but there was something about what he was doing with us that caught me in a very deep and powerful way.

Tippett: If I think about the culture of my childhood in terms of education, I was very much in the thick of an anti-intellectual, frontier America. And you also have written a lot about that strain, which takes different forms in probably different regions of the country, different socioeconomic groups. But talk to me about that as something that is a tension in our culture and even in the culture of our schools.

Rose: These tensions that you’re talking about, I mean, they go far back in the Republic, and it gets expressed in different ways. Sometimes it’s expressed in terms of rural or country or mid-America versus the city or East Coast elites or East Coast institutions. So there’s that sort of country-city tension that runs through our literature, back into the 19th century. And in fact, Sarah Palin was masterful at playing those guitar chords in her speeches.

So there’s that kind of tension, and hand in glove, there’s another tension that I understand. And it’s the tension between book learning and practical experience.

Tippett: Yes. And I think that was the tension that you were most acutely aware of when you were growing up.

Rose: Yes. And it’s a very interesting tension, to me. And again, it goes way back in our history. And part of what Hofstadter chronicles is the way the country shifts over time from more and more of a weight and credibility given to practical experience — the practical man, the wisdom gained through living versus the certification of schools, bookwork, intellectual endeavor, certification, all of that sort of thing; and we have moved into the 20th century, and we’ve become a culture of certification, a culture of school-based credibility and training and all of that sort of thing. So what you used to learn in the apprentice shop you now learn in a classroom.

So there’s this whole cultural shift, but the tensions remain. Somewhere, I quote my cousin, and I love this little saying because it captures so much. He says, he likes to say all the time, “You know, it took a guy with a college degree to screw this up and a guy with a high school degree to fix it.”

Tippett: [laughs] Right. That’s part of the American spirit, too. It really is.

Rose: It is, isn’t it? And, you know, Krista, I’ve got to say, given how I grew up and what I experienced as I grew up, I understand the legitimacy of the point of view that gives credibility to hands-on experience versus the abstractions that can so often emerge from just learning through books. And of course, what I strive for in my own work and with students who I’ve worked for, I strive to try and figure out how you blend these strands, because again, I’m very uncomfortable with binaries, with simple dichotomies, with, it’s either this or it’s that.

Tippett: Right, right. There’s above the neck learning and below the neck learning we talk about, and then we strip the intellectual out of physical work, and we strip the physical out of intellectual activity.

Rose: Right. And in fact, I think what happens in most kinds of good work, whether it’s styling hair or neurosurgery, is that you get this blend of formal training with hands-on experience. And the folks who best blend those strands are the people who are usually the best at what they do.

Tippett: One of your books is The Mind at Work, and let’s start there. We can talk about education and intelligence in the many forms it takes, but there’s this beautiful, there are these beautiful sentences. I think this may be the beginning of your book: “I grew up a witness to the intelligence of the waitress in motion, the reflective welder, the strategy of the guy on the assembly line. This then is something I know: the thought it takes to do physical work.”

I’m sure many people have made those kinds of observations, but again, I think it’s something we don’t sit down and formulate, [laughs] speak out loud, or read on the page like that.

Rose: [laughs] I guess I had no choice but to see things that way, right? As I grew up, my father and I, until he just became too sick to get out of the house, we would take the bus downtown and go spend time with my mother while she worked. We’d sit at the counter, or there was this back booth. In most restaurants there will be some little back booth where the cooks and the waitresses will take their breaks. And so we’d sit there, and I’d watch. I’d watch her work. And I mean, even to a child’s eye, it was just such an impressive display of competence.

Tippett: Well, and then you later interviewed your mother for this book.

Rose: I did. I did.

Tippett: So tell me about what you learned then, or what you were maybe able to put words around, about the mind at work in her waitressing.

Rose: Right. All of this training that I had gotten in the university, in graduate school, all this training in cognitive psychology and thinking about how people think, and all of that — it was this wonderful opportunity to take all that and bring it right back home, bring it right back to the kinds of work that all my forebears did, working in restaurants, or machinists and welders in the railroad yards, or working in the automobile factories when the automobile industry was booming.

And so what I was able to articulate better, through bringing this formal knowledge of cognitive science to bear on my mother’s experience, let’s say, I was able to make connections between her work and this lofty research taking place in research laboratories and, in a way, test that research with just the lived experience of her work in a restaurant.

So, for example, it helped me understand the complex memory work that waitresses, waiters in restaurants are able to do, especially in these big chains that have the rushes at breakfast and lunch where you see these folks just zooming through places. And they always seem, the good ones seem to know who gets the fried shrimp. They know who gets the chef salad. They know who gets that omelet. So they’re remembering that stuff. They’re remembering things about what the regulars like or don’t like. So all the memory work, and then all of the play of attention and vigilance, the constant kind of scanning of the workspace — who needs what, what’s going on, somebody dropped a fork, somebody else is waving. Oops, the manager’s seating some new people over there. Oops, you know what? It’s taken too long for that shrimp plate to come out, I’d better check on that. So there’s all that kind of stuff going on.

When you watch a waitress at rush hour, they seem so economical. They’re zooming through the place, but they’re not missing a lick. What’s going on is that they’re prioritizing, on the fly, the different things they have to do. If you don’t cluster these tasks together, you’re going to run yourself ragged. And so there’s a real efficiency that emerges in the middle of the action, on the fly.

Tippett: I mean, what it made me think of, when — you wrote about all kinds of work that, again, we think of as “physical labor.” And this is another experience we have all the time, but we don’t always name, is how there’s giftedness in every occupation, in a plumber or a painter or a waitress or a hairstylist, certainly. It is that mix of skill and intelligence and sophisticated knowledge and judgment and instinct that’s been honed by practice.

Rose: Especially in this high-tech era, where we are so captivated by electronic media, by the continued breakthroughs in technologies of all kinds. And absolutely, those are worth celebrating and worth marveling at. But what unfortunately happens is that our marvel at these new technologies plays into this unfortunate trend in the West of looking down on those who work with their hands — a tendency that goes all the way back to Plato and Aristotle, to consider the person who works with his or her hands ..

Tippett: Manual labor.

Rose: … manual labor of any kind, to be of lesser quality, to be soul-shriveling, to be — the Greeks even talked about it making one unfit for civic participation. So this tendency has been around for such a long time. And it’s so undemocratic, to my mind.

Tippett: Right, right. [laughs]

Rose: Right? And so I wanted to try and turn all that on its head and say, all right, let’s take these frameworks of intelligence and cognition and analyzing tasks that usually we reserve for white-collar folks, professional folks, biographies of scientists and entrepreneurs and whatnot. Let’s see what happens when we take these lenses and turn them on the folks who comprise the backbone of the economy and of what makes the world run: physical, manual labor; service work and that.

And what happened as I did that was just this revelation of what you were talking about: the knowledge base you have to build to be good at anything from styling hair to plumbing to welding to bricklaying, whatnot, and the deployment of that knowledge and solving problems with it and troubleshooting and making decisions on the fly. And it was just such a wonderful experience. What an excursion it was, for me, to spend this kind of time with these folks, folks I’ve grown up with, but spend this time with them and using that lens to kind of highlight and underscore the richness of their work, which just so often gets dismissed — until something goes wrong with our plumbing.

Tippett: Right. [laughs]

Rose: And then, suddenly, this is the most important person in the world. [laughs]

[music: “Turning To You” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being, today remembering the wisdom of the esteemed and beloved education researcher Mike Rose, who died this summer. I interviewed him in 2010.

[music: “Turning To You” by Blue Dot Sessions]

You know, there’s a question that you pose repeatedly in your writing, and I think we’ll come back to it again in this conversation — what kind of education befits a democracy? — which is very resonant with what you just said about how you’ve thought about intelligence and different kinds of work. And when you write about vocational education — I mean, I do think that the notion of vocational education has had a bit of a boon, in recent years. I mean, there is more attention.

Rose: Yes, yes.

Tippett: Also, as we become globalized, I’ve been aware that the United States compares itself to cultures like Japan or Germany, which have very robust vocational education sectors.

But something that you’ve pointed out — and I don’t know, I mean, I lived in Germany for a while; I’m not sure if this is true in those other cultures, but I think it’s true here —that even as we try to take this notion of vocational education more seriously, we strip out a sense of the cognitive and civic aspect — precisely what you’re describing. And you say the way that we talk about these students, who are not going to go to university but are going to be vocationally trained, is inflected with a sense of their limitation.

Rose: You know, if you want to look at a hundred-year institutional case study of what can go wrong when a culture holds to these kinds of diminished notions of the intelligence involved in everyday work, you look at vocational education, because when you go back and look at the origins of voc-ed in the 19-teens and ’20s, you begin to see that, even at the beginnings of it, there were these notions afoot. Like, for example: well, there are children who are “hand-minded.” That was a phrase that they used — “hand-minded.” And then there are those who are “abstract-minded.” Now, these were …

Tippett: I’m not sure either one of those sounds great. [laughs] Which option is better?

Rose: [laughs] Yeah. Well, getting back to something that’s dear to me is that hopefully all of us, to some degree or another, are both of those things.

Tippett: Right.

Rose: Right? But so imagine, then, you begin this enterprise that’s called vocational education, with notions like that: that separate whole huge chunks of young humanity into one category or the other. And, hey, no big surprise, the kids who are clumped into that hand-minded group tended to be poor kids, immigrant kids, kids of color. Right? And those who were moved or categorized as being the abstract-minded folks, well, gee, no big surprise, they tended to be white and here for generations and come from more well-to-do families. John Dewey, our great American philosopher, called this “social predestination.”

So at the very origins, the very beginnings of voc-ed as it manifested itself through most of the 20th century, you had these kinds of ideas about students, about intelligence, about work, about mental activity. So no wonder we ran into this situation where the vocational track ended up being, for many kids, a dumping ground. Now, having said that, I don’t want to deny for a minute that there weren’t great voc-ed teachers all the way along the way. There were, and people learned things. And so I don’t want to be dismissive of the enterprise.

But when you look at the whole trajectory of it, no wonder it ended up creating, within the school, this place where the intelligence of the work being done was not foregrounded, where kids at a crucial transitional point in their development are categorized as being not that bright, and the kind of curriculum they got, particularly outside of the workshops, was just, in many cases, not that stimulating and not that inventive.

Now, you’re right, in the last decade or two, there’s been a lot of money and a lot of attention paid to trying to revitalize voc-ed and to break this awful, 100-year-old barrier that separates the “vocational” from the “academic.” That’s another one of these splits. I’ve been talking about these dichotomies and binaries, right? That’s another one of these splits, I think, that have gotten us into trouble.

Tippett: You know, something that concerns me is when people talk about “meaningful work.” It’s one of those phrases that’s really out there in our vocabulary now, as people question some of the materialism that’s surrounded us or think about what are we as whole human beings, in this spiritual aspect. And you will hear people talk about the importance for human beings to feel that we’re doing something meaningful and purposeful with our lives.

And I think that’s a fact, but what concerns me — people will often say to me, I can’t tell you how many people will say, “You know, you must have the best job in the world.” But what they think is that I spend my time having these wonderful conversations. And, you know, I am incredibly grateful for my job, but what I say then: “Yes, but it’s a job.” I mean, there’s a huge amount of work and a huge amount that’s not romantic that goes into this. By the same token, I worry when we then romanticize certain kinds of work as meaningful that are more overtly meaningful, right? I mean, there are companies that are doing, producing products that are overtly more meaningful than other companies, right?

But I feel like we lose sense of all the different ways in which work is meaningful, and to me, you know, working to put food on the table for your family to eat also makes that work meaningful in some sense. I don’t know. I’m kind of throwing that out, because this is something that concerns me, that this is another way we might have of making people either feel good or bad about the work they do and their identity.

Rose: You know, I’m really, I’m so glad you’re bringing this up, because what you’re putting your finger on is that the use of this notion of meaningful work, which is a lovely notion, and as you say, what’s the bottom-line thing that drives our lives? It’s to have some kind of meaningful life; to not just be a blip and that’s it, you know? So that’s all well and good. But what I like about what you’re doing here is you’re putting your finger on the fact that the way people talk about meaningful work can inadvertently have a very elitist tinge to it.

Tippett: Yes.

Rose: So let’s then bust this notion of meaningfulness open, right? Let’s think about this. As you say, regardless of the kind of work, to be able to support a family or put food on the table, that’s meaningful. For my mother, doing this kind of work, which was very hard work, and it took its toll on her, physically, but it was a way for her — and she talked about this a lot — to be out in the world. She saw that job as a kind of social sphere, a social field. She talked all the time about being among the public and what that meant to her. So for her, then, in the midst of this difficult work and difficult circumstances, there was great meaning in the kind of social dimension of it, right?

Conversely, you and I both know people who are doing work that the culture at large, from a distance, would say is really meaningful — and they’re miserable.

Tippett: Really ennobling. Yeah, exactly.

Rose: You know? They’re as unhappy as can be. You know, the miserable lawyer, the unhappy neurosurgeon, right? There’s those, too. So meaningfulness is a more fluid and rich and variable concept, I think, than we tend to imagine.

[music: “Oobleck” by Kaki King]

Tippett: After a short break, more with the late UCLA education research professor Mike Rose. He died this past summer, at the age of 77.

[music: “Oobleck” by Kaki King]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, a conversation on work, education, and civic imagination, with the esteemed and beloved education researcher and professor Mike Rose. He died this past summer. I spoke with him in 2010 about his research into the often-ignored intelligence in service professions and physical labor, jobs like that his mother did, as a waitress for over 35 years.

Mike Rose was the first person in his own family to attend college, and he spoke often about a handful of teachers who made all the difference for him, shaping his essential understanding of good teaching. He said this: “Such teachers don’t merely inspire thought. They give students a sense of what opportunity feels like.”

So let me ask you a question now that I thought I might ask you earlier in the conversation, when you talked about Jack McFarland, this English teacher who kind of set your mind on fire. There again is an image that’s both tactile and visual and cognitive. And then you write about going to Loyola college, and it was only very recently that you’d even thought that college would be something that was in your life. And you had other teachers, and you wrote these were mentors who “collectively gave me the best sort of liberal education, the kind longed for in the stream of blue-ribbon reports on the humanities that now cross my desk.” What is your imagination about the best kind of liberal education that you both received and that you know, that you think about and work on now?

Rose: Right. I should say that that college that I went to was the only place I could get into. And I got in there because Jack McFarland, my high school English teacher, had gone there himself, seven or eight years before, and he knew some folks there. So he went over and talked to them, and he got me in as a probationary student. So there I was. [laughs] There I was, and boy, once more I found myself at a loss. My freshman year didn’t go so well, and at one point I was getting close to not fulfilling the terms of the probation.

Let me just say, by the way, an aside here. We’re telling a lot of stories, and I’m telling you a lot of personal stories, but I hope that what comes through is that these things that I experience, or other folks I talk about, are commonplace. I mean, something that I see happening throughout my career in working in different kinds of preparatory programs is the phenomenon of the young person who does well in high school — or does well in part of high school, anyway; is the pride of their neighborhood, and then they come to college and run right up against a brick wall, because it’s a whole other ballgame, right? And it’s larger, and it’s anonymous, and there may not be a system of support there.

So that same thing happened to me. Well, again, sheer dumb luck, I managed to get some professors, mostly in English, starting in my sophomore year; they really devoted themselves to their teaching and their students, and they taught me a lot of things about history or literature, how to write, how to write better — they certainly did that. But they were also people whose office door was open and who would spend a lot of time talking about the material you were learning and would work over a piece of your writing. I can’t tell you how many times, Krista, I’d be sitting at the elbow of one of these folks, and they were going over a paper yet once again and saying, “You know, try saying it this way. Try it like this.” So all of that kind of personal attention, that embodiment of knowledge in a relationship.

And it seems to me that that finally is what good teaching is all about. And that’s all the way from good teaching in kindergarten through graduate school, through medical school, through apprenticeships, through the carpenter’s workshop, you name it; that somehow or another, skill and knowledge is integrated into some kind of a human connection, in that it was a humane humanities education. It was, certainly, was rich cognitively, but it was that interplay of the cognitive and the social, the personal and the cognitive.

Tippett: And something you also have concluded with your work with remedial education, and that you describe in your own experience at Loyola, was how what worked wasn’t dumbing it down for you and then making it really simple. It was also about high expectations, but then supporting that; so expecting you to write papers, but then helping you get it right. But I wonder, also, if that relationship piece isn’t what makes that possible.

Rose: Absolutely. But you bring up another point, and I really want to touch on it. We’ve been talking about these assumptions in the culture about intelligence and ability. And one way we’ve been talking about it is that there are these unfortunate strands in the culture that connect physical work with low intelligence. Well, there’s another strand, and that unfortunate strand has woven its way through remedial or developmental or basic skills education. The assumption is, if someone can’t do something, then it indicates some deficiency, some deficit. And our tendency has been then to take whatever task it is, whether it’s mathematics or writing or reading, and break it down into the tiniest little morsels. But it seems to me that this approach we’ve taken has just not been that productive.

So what do you do? Well what you do do is you create conditions where, right from the jump, you’re giving people intellectually engaging material. And even if their skills are so poor that they can’t read it, you read it for them. You get the conversation going around this question in political science or in sociology or in a piece of literature. You bring in concepts. Maybe you have to scale things down a bit. Maybe you even take a piece of reading and you edit it down. Maybe you rewrite it, even, so that it’s a bit simpler to use. But the point is, is that you throw people into the activity, and then along the way, you address the bits and pieces. You don’t let those go by the wayside, but you integrate them into a meaningful engagement that makes them feel like, you know what, I’m in the middle of something here that I haven’t been in before.

Tippett: You know, something that reading your work, reading your stories about yourself and all the many people you’ve worked with, what it reminded me of, what it kind of immersed me in were my own memories of those moments when my mind came to life. I think you use the word “yearning” in your writing. It’s an ache, as much as it’s a thrill. You actually — I meant to bring this with me, and I didn’t, but you have a paragraph from a book — I did write the title — The Metaphysical Foundations of Modern Science, which was assigned to you in those early days when you didn’t know what you could achieve. And it was this paragraph that you had to go over and over and over again and underline, where it made your brain hurt, and it felt so good, because it somehow opened possibility.

And I don’t know, what this also makes me think is how precious these educational experiences are, because when we get into what my father would call “real life” — you know — capital “r,” capital “l” — you know, those are special moments. And maybe you can have them when you’re 80, not just when you’re 18, but you get to be present to that a lot. That’s a great thing about your work, I think.

Rose: I think it’s really a — those are powerful moments, and they can be defining moments. When you talk to people about their memories of school, memories of teachers — certainly, you’ll get some bad memories and awful teachers and that sort of thing; that’s to be expected. But when people talk about either falling in love with a discipline, falling in love with a subject matter, or a teacher who made a difference, it’s interesting how often they’ll remember a moment. They’ll remember something that they read or something that somebody said or something someone did for them. Those moments are powerful, and I think they live on in memory for a reason, because they help shape who we are and where we go, those moments, as you put it, of possibility.

And you’re right. I mean, I’ve been really fortunate to be close by as those moments erupt. And I guess the point I want to make, about those moments and “remedial” or basic-skilled education or students who haven’t done so well in school — again, this is another unfortunate binary that we fall into — I think a lot of folks would just assume automatically that those moments happen all the time with kids who have good educations and go to good schools and have good teachers. They also happen all the time, and are always at the ready, with folks who are even coming in with the most basic of skills and the longest way to go. It happens if you can create the right kinds of environments for them.

[music: “Milk Tea” by Kido Takahiro]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being, today remembering the wisdom of the esteemed and beloved education researcher Mike Rose, who died this summer. I interviewed him in 2010.

[music: “Milk Tea” by Kido Takahiro]

You make a very interesting point about how our education across recent decades has been so shaped by psychometrics and tests and measurements. And you make a really interesting proposition, and this applies very much to the college-bound — that a high score on a lot of these tests we use, like, let’s take the SAT, does tell us something we can work with, but a low score tells us less, is less useful. [laughs] So you said it’s a measure that only works at the upper end of the scale. That’s really interesting.

Rose: Yeah, I really think that’s true. It’s like we have a ruler that is very precise for half of its width or length, right? I’m interested in those folks that don’t do well on those kinds of tests, that don’t do well on the standard IQ test or don’t do so well on the SAT test, let’s say, because, again, what I want to know is, I want to know what they know that’s not being reflected in that test. Or another angle on it is, I want to find out more about what didn’t happen in their educations that made them do poorly on that test, or in their life experience.

So let’s take the IQ test. That’s a kind of standard instrument in our culture for the last century. If someone does well on an IQ test, that certainly tells us something, right? They’ve got some smarts; there’s no doubt about it. But think of the folks who might not do so well on those kinds of tests, because they didn’t have a lot of formal schooling, and everybody admits that there’s a direct correlation between amount of formal schooling and how well you do on tests like that. There’s an intimate connection between those two things. So they didn’t have a lot of formal schooling. They haven’t had a lot of experience taking those kinds of tests. They also don’t invest as much in them, right? I mean, those of us who have been through a ton of schooling, we’ve been socialized to know that when one of those things appears in front of us, we better try our damnedest to do well on it. So there’s all kinds of reasons through which we can explain somebody not doing so well on a test like that, reasons other than some intellectual deficiency.

So then I say, I’m interested in, well, gee, what happens when we go out into the world with this person and we watch them work, let’s say? Or we watch them raise kids? Or we watch them figure out how to make their way through the day or some complicated social relationships? What emerges that bespeaks of intelligence? What goes on right under our noses that bespeaks of some kind of smarts? So the plumber who reaches up inside of the wall of an old building where he cannot see and he can only feel, and through feeling around the structures in there — feeling the rust, feeling moisture if there’s any, feeling the way the thing is structured — he’s visualizing what’s back there that he can’t see and then bringing a knowledge base to bear on trying to figure out what the problem may be. Think of what a complex set of mental operations are involved in that.

Or the hairstylist who is presented with someone who comes in and they have a botched dye job, let’s say. And the stylist — and this woman said this to me, when I was watching her work, she said, “The first thing I ask myself is, what was that previous stylist trying to accomplish?” So what an interesting question to ask, and what an interesting problem-solving road that takes her down. Now, those kinds of things are not going to be picked up on an IQ instrument. They’re not structured to get to that stuff. But those are certainly manifestations of intelligence.

Tippett: Right. We hear a lot about, and you’ve written a lot about how we’ve reduced this reductionist approach that we were just getting at a bit — you know, testing, standardized testing. But I’d like to ask you, what do you see, when you look at the big picture of what’s happening with education?

Rose: Well, you know, unfortunately I see that we are locked into a way of thinking about school reform that suffers from so much of what else we’ve been talking about in this conversation, and that’s a kind of a reductive approach to schooling, to learning, to teaching. I think the unfortunate thing is that if you really know about schools and you really know about teaching, you get in close to classrooms, you watch this very intimate and difficult and complex thing called teaching and learning, you see what a far remove a standardized test score is from the cognitive and emotional and social give-and-take in a classroom.

I contrast that with a journey that I took around the country a while back, spending four years when I could get the time, visiting good public-school classrooms, many of them in poor or modest income districts, many of them rural, some urban, spread all across the United States. And the kinds of things that I saw there, and the kinds of qualities of good teaching and the kind of learning that goes on, I think can, in part, some little piece of it, some aspect of it will certainly be picked up by the kinds of testing regime that we put in place, but certainly not all, and certainly not the kinds of things we’ve been talking about.

My hope would be that we get to the point where we begin to look for much richer ways of thinking about teaching and learning, and richer ways to try and assess what’s going on in schools and classrooms, because here’s the good thing about the current impulse, is that it is admitting and putting a bright light on the fact that there are a lot of kids who don’t do well in our schools; and those kids tend to be — tend to be — poor kids, immigrant kids, children of color; and that we absolutely have to do something. This is a moral, ethical question of equity. We have to do something to do better with those children.

Tippett: You ask a rhetorical question in your writing, sometimes: when was the last time you heard a really moving speech about education? And I think about this in other contexts, as well. I mean, the word “education” itself has become laden with — the word “education” doesn’t inspire. I mean, it should. But you almost interchangeably use phrases like “human possibility.” I mean, reading you made me wonder if we just also need to think about the language we use. Another question you ask is, what kind of education befits a democracy? So what is the answer you would give at this point?

Rose: Well, the language we use is hugely important, and it gets to what we’re talking about here: that if the language we use is a strictly instrumental, functionalist language that says we go to school, we send our kids to school, because we want to compete in a 21st-century economy, and therefore, we’re going to hit these subjects hard, and we’re not going to hit these other subjects, like music or art or literature or even social studies — if that’s the language we’re using and that’s the way we think about the purpose of schooling, it’s going to dramatically narrow what happens in schools. It’s going to change the way we think of what it means to be educated. And that has implications for, I think, who we are as a society.

So what kind of a language should we use in a democratic society? Certainly, a language that includes the economic motive; absolutely, of course, but that braids that motive in with all the other reasons that actually, historically in our country we’ve talked about as well: the civic motive. We send kids to school to become civic beings. We send kids to school to learn how to solve problems with each other. Children go to school because their parents want to help them develop into better people. They want them to find passions. They want them to learn how to learn.

And what about, in a democracy, learning how to speak up when you think something is not right? Or learning to take a risk? You know, in this kind of test-based world that students grow up in, you’re penalized if you take a risk. But yet, just about any intellectual breakthrough of any kind that you’ll study has seen that it’s been a path of breakthrough and failure, of risk, of going beyond. So where in all of this are children encouraged to take intellectual risks? What kinds of classrooms are created that allow that? Do you see what I mean, when I say the language we use either …

Tippett: Yeah, is essential.

Rose: … it either closes down or opens up the richness with which we think about schooling in a democracy, because in fact, what you see when you travel through all these communities and you talk to parents, and you watch these teachers who work so hard, and you spend time with these kids, is you get a sense of this immense rich thing that a classroom can be, a place of both learning subject matter, but of learning how to exist in a public space and how to have this feeling, this sense, that you matter and that your mind matters and that this is a place that’s safe and respectful and where I can take chances and I can learn something. And that can have an effect on who I’m going to be.

[music: “No Spirit Animal” by Small Sails]

Tippett: Mike Rose. He died on August 15, at age 77, after a short illness. He was a research professor in the UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies. One of the last subjects Mike was pondering and writing about was “Public School and the Social Fabric.” An essay he wrote on that title will be published in 2022. His books included Back to School: Why Everyone Deserves a Second Chance at Education and The Mind at Work: Valuing the Intelligence of the American Worker.

[music: “No Spirit Animal” by Small Sails]

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Laurén Drommerhausen, Erin Colasacco, Eddie

Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Julie Siple,

Gretchen Honnold, Jhaleh Akhavan, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Ben Katt, Gautam Srikishan, Lillie

Benowitz, April Adamson, Ashley Her, Matt Martinez, and Amy Chatelaine.

[music: “Deep Water” by David Byrne]

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and

composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear, singing at the end of our

show, is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent, nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American

Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find

them at fetzer.org;

Kalliopeia Foundation, dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality, supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on

Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org;

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives;

The Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its

founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education;

And the Ford Foundation, working to strengthen democratic values, reduce poverty and

injustice, promote international cooperation, and advance human achievement worldwide.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.