Molly McCully Brown

Transubstantiation

Are there places you’ve lived or visited that others would disregard? What do you see in them that others might miss?

This poem takes place at night, describing a scene from a town on the edge of a city. The poet feels at home in a “nowhere” town, with cattle pacing in the fields, boarded houses, and rowdy filling stations. This is a place that through the eyes of some would be considered a “shit town,” but to the poet it is home.

Image by Expedition Press/Expedition Press, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

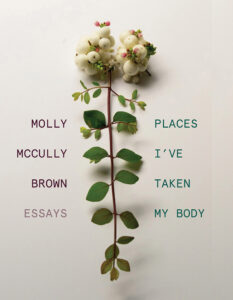

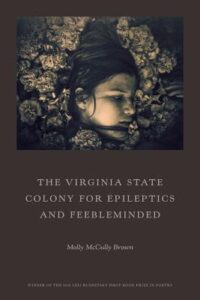

Molly McCully Brown is the author of The Virginia State Colony For Epileptics and Feebleminded, which was named a The New York Times Critics’ Top Book of 2017, and the forthcoming essay collection, Places I’ve Taken My Body. She teaches at Kenyon College, where she is the Kenyon Review Fellow in Poetry.

Transcript

Pádraig Ó Tuama, host: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and I’m often awake in the middle of the night. And I like looking at things in the middle of the night, looking out the window, or going outside and seeing what’s there, and listening to the sounds of the city or the countryside in the middle of the night, because things sound different, then. Things that are strange become familiar or calm down, and things that are familiar become very strange.

[music: “Every Place We’ve Been” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Transubstantiation” by Molly McCully Brown:

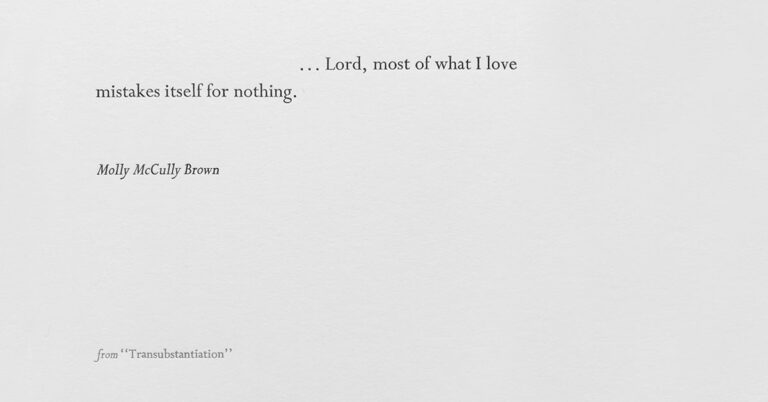

“It’s the middle of the night. I’m just a little loose on beer, and blues, / and battered air, and all the ways this nowhere looks like home: / the fields and boarded houses dead with summer, the filling station rowdy / with the rumor of another place. Cattle pace the distance between road / and gloaming, inexplicably awake. And then, the bathtubs littered in the pasture, / for sale or salvage, or some secret labor stranger than I know. How does it work, / again, the alchemy that shapes them briefly into boats, and then the bones / of great felled beasts, and once more into keening copper bells, before / I even blink? Half a mile out, the city builds back up along the margin. / Country songs cut in and out of static on the radio. Lord, most of what I love / mistakes itself for nothing.”

[music: “At Dusk” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: This poem comes as part of an interlude from a book that explores, imaginatively, the legacy of a building and an institution called The Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, which is a true place; she grew up near it. And this poem is part of the interlude, and in this interlude, we’re in a nighttime vista that seems to mistake itself for nothing, an abandoned place. And she’s locating us here, in rhythm and rhyme and image. And the poet is inviting us into the imagination of the poet, that says, this place is loved, even though it imagines itself as nothing, even though it imagines itself as unlovable. This isn’t charity. I don’t think this is a poem that’s trying to be pitying or show sympathy. This is a poem where somebody is relaxed and loosened up by beer and is telling the truth. And this is a poem where the poet sees alchemy, sees magic, and has a powerful message about the ways in which someone might imagine a place or a person or an area or a population as discardable — useful, only, but not valuable for itself — and invites us into a different way of looking, to see the multiple possibilities of meaning and use and their own magic, that people and places have.

[music: “At Dusk” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: The narrator in this poem has an extraordinary, expansive gaze and can see all around, from the cattle to the bathtubs to the filling station, “rowdy / with the rumor of another place,” and there’s the city off in the corner. This poet knows so much and travels so much in this poem, as opposed to falling into a category that somebody might have, for a poet who’s a wheelchair user, and what the expectation of the kind of poetry that that poet might write.

It’s a night poem, and I think it’s an important thing to recognize, that this “gloaming” light that she speaks about, this strange light that’s present in the middle of the night. And she’s speaking about the “battered air” at the start of the poem, and I always wonder, what is battered? Is it like an old car, or an abandoned car? Is this about a former industrial place that’s now post-industrial? Why is the air bruised or battered? Maybe something from which much is asked, but little is given back. Maybe there’s a lot of factories there. And she sees that this place, this nowhere, nonetheless might look like home.

The bathtubs are so interesting. She speaks about the bathtubs as being “littered in the pasture.” And I assumed, when I read this at the start, that if there were bathtubs in the pasture, they’re for the cows to drink from, to put water in it and to just use as a trough. But she has all these questions about the bathtubs. They’re “for sale or salvage, or some secret labor stranger than I know.” Suddenly, these bathtubs have multiple functions. And then she speaks about them maybe being like a boat, somewhere to go, or a beast in and of itself, or a bell, bringing music into it again. And in this gloaming alchemy that she’s speaking of. The magic seems to be that this nighttime hour suggests that things have many functions, not just one. And she seems to be introducing to these various things that she can see, the possibility that things that think they’re just on the road to nowhere, could begin to imagine that they can be many things.

[music: “Fjell_Flor Vjell” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Ó Tuama: I get the impression that this is a poet who very muscularly is saying, places like this need to learn that they are lovable and loved and can be called this. She’s describing this scene with a kind of a home recognition. And it doesn’t seem beautiful; it seems abandoned, like a halfway place. But the final line, “Lord, most of what I love / mistakes itself for nothing”

I think the usage of the word “Lord” is so interesting, because it reminds you of an old hymn, or a kind of a sigh, but she’s not saying, “Lord, you love all this.” It’s not God’s love that’s being evoked, it’s her own. It’s the poet’s love. “[M]ost of what I love / mistakes itself for nothing.” And there’s a call from that observation, I think, to consider, what would it be like if those places that mistake themselves for nothing, those things that mistake themselves for nothing, actually could begin to believe themselves to be something? What does it mean to take yourself, that you might have mistaken for nothing, the self that you might have thought as a halfway or something that people just pass through or abandoned or something that needs to be fixed or is unfixable, what would it mean to pay attention to that and to consider that love is an economy that can bring something powerful?

[music: “Every Place We’ve Been” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: This poem is called “Transubstantiation,” and that’s the word that Catholics use to describe what happens when the ordinary elements of bread and wine get inhabited by the presence of God, during the Communion, and are changed then into the body and blood of Christ. And this poem seems to be imagining that the ordinary stuff of an agricultural suburb, caught between blues and country in places where things shift and people only pass through, this poem seems to imagine that this can be transformed into something. And the question is, by who? What is the transubstantiation? Who’s the priest here? And it seems to be, the poet is the priest here, looking around at a place that seems functional, industrial, maybe tired and battered, and is giving a name to a place that considers itself to have no name, is giving something sacred to something that considers itself desecrated.

[music: “Every Place We’ve Been” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: I grew up in a village, Carrigaline, on the outside of Cork City. I liked it; we were on the edges of that village. There was a lovely view across the fields. There was lots of places that weren’t finished off; somebody had had an imagination of building a house and had run out of money, so there was abandoned building sites around the place, but they were beautiful in the sunset and the sunrise. I always liked the whole area. It’s much more built up now, which I sometimes feel sad about, but I’m glad that people have found their home in that village.

I hear, sometimes, people say something about the village to say, “Oh, it’s a bit of a shithole, it’s a place that you pass through to get to the beach.” But it’s impossible for me to hear the name of the village without even this sense of all the love — and loneliness — that went into growing up in a village: the way that I knew the faces of all the teachers and every person in a school; the way that you knew the faces around the village; the ways that I wished for more friends and didn’t have any; all the loathing and the longing and the loving that goes into being a teenager. As an adult, now, I return to that place, and the streets and the shops are filled with my experiences of those. And I can’t see this as just another little village, because it was the village that I grew up in, and it’s filled with my own story and how I have projected myself into those things and how those things formed me, too.

[music: “The House You Wake In” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Transubstantiation” by Molly McCully Brown:

“It’s the middle of the night. I’m just a little loose on beer, and blues, / and battered air, and all the ways this nowhere looks like home: / the fields and boarded houses dead with summer, the filling station rowdy / with the rumor of another place. Cattle pace the distance between road / and gloaming, inexplicably awake. And then, the bathtubs littered in the pasture, / for sale or salvage, or some secret labor stranger than I know. How does it work, / again, the alchemy that shapes them briefly into boats, and then the bones / of great felled beasts, and once more into keening copper bells, before / I even blink? Half a mile out, the city builds back up along the margin. / Country songs cut in and out of static on the radio. Lord, most of what I love / mistakes itself for nothing.”

[music: “Praise The Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Lily Percy: “Transubstantiation” comes from Molly McCully Brown’s book The Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded. Thank you to Persea books who gave us permission to use Molly’s poem. Read it on our website, at onbeing.org.

Poetry Unbound is Chris Heagle, Erin Colasacco, Serri Graslie, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Christiane Wartell, Karen Navarre, Karyn Towey, Sue Ariza, and me, Lily Percy. Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions. This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. We also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me — find those wherever you like to listen or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.