Nick Cave

Loss, Yearning, Transcendence

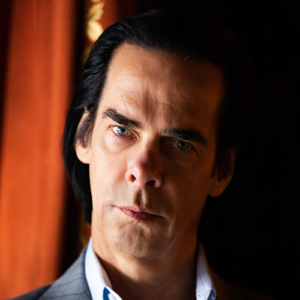

Here are some experiences to which Nick Cave gives voice and song: the “universal condition” of yearning, and of loss; a “spirituality of rigor”; and the transcendent and moral dimensions of what music is about. This Australian musician, writer, and actor first made a name in the wild world of ’80s post-punk and later with Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds. He also underwent public struggles with addiction and rehab.

Since the accidental death of his 15-year-old son Arthur in 2015, and a few years later, the death of his eldest child Jethro, he has entered yet another transfigured era, co-created an exquisite book called Faith, Hope and Carnage, and become a frank and eloquent interlocutor on grief. As a human and a songwriter, Nick Cave is an embodiment of a life examined and evolved. He sat with Krista in the On Being studio in Minneapolis, and the gorgeous conversation that followed is woven in this episode with his gorgeous music.

Image by Joel Ryan, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Nick Cave is the songwriter and lead singer of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds. Their albums include Ghosteen, Skeleton Tree, and Push the Sky Away. Nick's recent albums with frequent collaborator Warren Ellis include Seven Psalms and Carnage. His book, which takes the form of an electric conversation with journalist Seán O’Hagan, is Faith, Hope and Carnage. He frequently writes, and answers questions from his fans, on the website The Red Hand Files.

Transcript

Transcription by Alletta Cooper

[music: “Into My Arms” by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds]

Krista Tippett: Here are some experiences to which Nick Cave gives voice and song as exquisitely as anyone with whom I’ve ever spoken: the universal human conditions of yearning, and of loss; a spirituality of rigor; and the transcendent and moral dimensions of what music is trying to say.

This Australian musician, writer, and actor first made a name in the wild world of ‘80s post-punk and later with Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds. He also underwent public struggles with addiction and rehab.

[music: “Into My Arms” by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds]

Since the accidental death of his 15-year-old son, Arthur, in 2015, and a few years later the death of his eldest child, Jethro, he has entered yet another transfigured era. He’s co-created a gorgeous book called Faith, Hope and Carnage, and become a frank and eloquent interlocutor on grief to the many who write him on his blog called The Red Hand Files.

[music: “Lavender Fields” by Nick Cave & Warren Ellis]

As a human and a songwriter, Nick Cave is an embodiment of a life examined and evolved.

[music: “Lavender Fields” by Nick Cave & Warren Ellis]

Nick and I, as it turns out, crossed orbits in the divided Berlin of the 1980s, though we were clearly having very different night life experiences. Now, with both of us a few decades older, he came to see me in the On Being studio in Minneapolis, and I am beyond thrilled to share Nick Cave’s voice in words and song with you.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[music: “Lavender Fields” by Nick Cave & Warren Ellis]

Tippett: So, a question that I start most of my interviews with is just wondering about whether there was a religious or spiritual background to your childhood, however you would see that now or define it now.

Nick Cave: Yeah, in many ways — My parents went to church every Sunday, but I don’t think they were religious and I don’t think that they believed in God, but it was a small town essentially, and that’s just what you did. I ended up singing in the choir for a couple of years, 10 to 12, and was quite fascinated by that. I enjoyed listening to the stories from the Bible.

I was different than the other kids who just hated that stuff. I actually liked Sunday school, for example. But I also feel I had, when I look back, a kind of weird over-interest — or I was weirdly drawn toward the figure of Christ, I would say, from a very early age; I just found the story fascinating. Way before matters of whether God existed or anything like that, there was just something about this story that I found very strange. I still do find it very strange, actually. Based around this sort of tortured individual, literally, and I just found that compelling in some way. And I relate to it, too.

Tippett: Say some more about that.

Cave: Well, these days I relate to it more because there’s a sense, especially in the scene of Christ in the garden praying and a God that had withdrawn his favor. I relate to that. I find that a compelling story and very beautiful, too, and very human. The sense of yearning, the sense of being tethered to the earth but reaching beyond ourselves in some kind of way is the story, I think, of everyone in a way.

Tippett: I was going to say that the word “yearning,” you just used the word “yearning” and it surfaces again and again. It feels like a really central — not just a concept or a word, but an experience.

Cave: For me?

Tippett: Yeah, for you. In life and in the life of faith.

Cave: Yeah. I don’t think I’m alone there. I think that most people have that feeling and a kind of lostness, I would say. An incompleteness and the need for something beyond ourselves to make sense of things. That’s how I’ve really felt since my first child died. And that yearning feels to me a kind of universal condition, based on a universal feeling of loss, shall we say. Does that make sense?

Tippett: Yeah, it does. It’s such a wonderful, evocative word. I feel like the way you talk about it is really — it’s a theological notion and I feel like we could go down a rabbit hole. Is it when Augustine says “our hearts are restless,” right? It’s another word, it’s your word for “our hearts are restless until they rest in thee.”

Cave: Yeah, that’s right. It feels to me that loss is our universal state as human beings. I disagree with the sort of “grief club” and the club no one wants to join. I think humanity itself is that club and that we are all feeling these senses of loss, whether it’s directly personal, it’s bred into us, that sense of yearning. And that’s not a failure. It’s a condition. To have these feelings, that we’re being intellectually dishonest or all these other arguments against these essential feelings. It is our condition. And I think that if we’re honest with ourselves, most people feel this way: a sense of lostness about things and a need for something beyond that. That’s my defense of religion, I guess. [laughs]

Tippett: Well, my most elemental definition of spiritual life at its best is that it is about befriending reality. That it helps us befriend reality, which means…

Cave: You mean the way things are?

Tippett: …Yes. Which means befriending the bedrock fact of loss, this condition, just what you described. And so this book, Faith, Hope, and Carnage, really grew out of a conversation. And it was during the pandemic, right?

Cave: Yeah, it began — Yes, it was. Right at the beginning of the pandemic, weirdly enough.

Tippett: One thing that strikes me is I feel like the whole world, the ground was shaking beneath all of our feet. And Western society in particular actually doesn’t have a very reality-based view, kind of resists this notion that loss is part of the human condition.

Cave: It ends up being a defensive position to hold because —

Tippett: And then brittle when things don’t —

Cave: Brittle?

Tippett: Brittle, yes…

Cave: Brittle, yeah.

Tippett: …when things don’t go well.

Cave: Yeah. Yes. I mean, there’s personal loss and the sort of obliterating effects of grief, if you actually lose someone, if a parent loses a child, for example, or you lose — Where the loss of someone dear to you impacts on you terribly, and it becomes this obliterating thing.

But I think that there’s also, as you say, a kind of underlying bedrock within humanity, too, of a historical and personal loss that exists. This, to me, this is our condition. This is the common binding condition of what it is to be.

And in that respect, I don’t think the common thread that runs through humanity is greed or power or these sorts of notions. It is this binding agent of loss. That, to me, is the thing that makes me able to look at anybody and feel connected to them, regardless of who they are. And I think there’s a power in that that isn’t really recognized.

Tippett: That’s so interesting. I think a lot about how fear and hate and violence are two sides. That behind what we see as violent, the manifestation of violence is fear metastasized. And what you’re saying also is what we look at —

Cave: That fear is behind the —

Tippett: Yeah. At the root of. And this idea that it’s actually this lostness, this sense of loss or fear of loss that is behind greed. And what manifests, what shows itself as —

Cave: And it’s the way we deal with that. It can be enormously creative and create extremely beautiful things, but it can also be the other way. We can become resentful, we can become completely concerned with our own inward situation. So it’s not necessarily — Loss is a kind of opportunity that can go either way, I think.

[music: “Waiting for You” by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds]

Tippett: At the beginning of this book, there’s this line from Isaiah: “A little child shall lead them.” And for you, the death of your son, Arthur — Well, I want to say it this way. I want to use, also again, a theological word. I feel like in his death, as in his life, he transfigured you.

Cave: Yeah. Look, for me, what happened to me is that I just rolled along with life. I had some kids. I loved the kids very much, and life just rolled along as it did. It didn’t have actually the dimension that it has now. And the death of Arthur — two of my sons have died, but the first one to die was Arthur — that had an obliterating effect on me and Susie. Not on our relationship, but individually.

It just drew us down a path of which we had no control whatsoever. It was not an ordered stroll through the stages that we’re supposed to go through when we grieve or anything else. It was an obliterating mess. It was a mess. I could see what happened with Susie, it happened in front of my eyes.

Tippett: That’s Arthur’s mother, your wife?

Cave: Pardon?

Tippett: Your wife, Arthur’s mother. Yeah.

Cave: My wife, Susie, sorry, yes. And Arthur’s mother. An essential change in her condition of being, of what life was to her. It was extraordinary thing to see. It simply happened to her. It wasn’t a matter of strength, it was just this thing that happened to her. I think the same thing happened to me. It was an enormous, defiant, creative energy that took Susie from being a regular woman that lost her child — was utterly obliterated by that — sort of rise out of that within a relatively short time — it’s not that she’s in any way out of it, or that there’s ever been any closure — but to this defiant, dynamic force that came out of that. It was an extraordinary thing to see and incredibly helpful and inspiring to me, too.

I think that there was a sort of zeal attached to grief, of seeing the world in a completely different way. I don’t see the world in the same way as I did before. It’s much more complex than I thought and much more fragile. And this creates a different feeling towards people in general. I found, anyway. I hear that a lot, that grief and empathy are very much connected, in the same way as loss and love are very much connected, too. And that the common energy running through life is loss, but you can translate that into love too, quite easily. They’re very, very much connected. And that comes around from an understanding of just how fragile and vulnerable and precarious the nature of life seems to be.

Tippett: There’s something that you said in the book, and I think you’re talking about this, but I’d like to hear a little bit more. So: grief makes demands on us.

Cave: Yeah. Yeah. I felt — What I’m doing now, this podcast, this conversation, for example, it’s not something that I chose to do, in a sense.

Tippett: Right. Right.

Cave: Or where I am now with things, it’s not something that was part of a master plan or something. Things just changed, and I found myself in this weird situation. I was quite happy being a musician and talking to Rolling Stone and Mojo [laughter] about the latest record, or whatever. I was quite happy doing that. And in some way too, I think a lot of my fans were quite happy that that’s what I was doing. [laughter]

This thing that’s happened, everyone’s had to deal with in some way. There’s this beautiful creative madness that goes on with grief where you simply don’t know what you’re doing, and you think you know what you’re doing at the time, but you look back and think, “What was I thinking back then?”

For example, very early on, I decided to do a tour, go on tour and stand on stage and talk about this and ask questions and people could stand up. And people said, “What are you doing?” And I said, “It just felt like something I needed to do.” But when I look back on it now, it was a strange thing for me to attempt to do. It was a kind of disorder about things that allowed me to just — It was like it didn’t matter what I did, I just went and did whatever I felt like doing. It’s a strange thing. I don’t know if that makes any sense.

Tippett: It does. It does. There’s mystery in this. And for you, this experience of grief, and an experience of God, or of what religion might be, are also intertwined in that way. Do you know this language of thin places and Celtic spirituality, that there are thin places and thin times where the veil between…

Cave: Oh yeah, I do know. Yeah. Yeah.

Tippett: …heaven and earth, the temporal and the eternal, is worn thin?. It feels to me like that’s an image also for what kept coming through to me in how these dimensions of experience, of mystery, of being human came together in you.

Cave: I think in the book, I called it “the impossible realm” or something like that, or it was something that I felt very strongly — I still feel strongly too at times — that there was a positioning of oneself, where I felt deeply connected to those that had passed on. Because it wasn’t just Arthur, and then Jethro died, but also other people, too.

Tippett: You lost your mother and —

Cave: Yeah, and I lost my father earlier on.

Tippett: Right. Yes.

Cave: I still feel this sense of otherness about things, that it’s not the imagination and it’s not dreams or the imagination. There’s just a way of being where I feel more connected to this other side, which is maybe that thinness you’re talking about. Certainly, you become exercised. So much of your time, when you’re grieving, is spent right up against loss and death and the one that you’ve missed, and absence and disappearance and all of this sort of stuff, incompleteness, these things, you’re just crushed up against this feeling. And maybe that’s the thinness of the veil, that dimension feels to sort of leak into your life in some way.

Tippett: Yeah. Here’s something you said in the book. “Perhaps grief can be seen as a kind of exalted state where…” — here’s the part — “…the person who is grieving is the closest they will ever be to the fundamental essence of things,” which is a very mysterious statement to make.

Cave: Yeah.

Tippett: And there’s also the mystery that what we’re talking about exalts some people and crushes others, right?

Cave: That’s for sure. That’s for sure. Yeah, it’s a beautiful way of putting it actually. You either turn around and look at the world and look at people in it or you don’t, and you just look inward and you gaze into the absence of that person. That’s like the abyss that you look into, it’s an absence. And I understand that impulse. There’s even a kind of deification of that one that is no longer with us, that’s extremely dangerous. There’s all these feelings of — that there’s some sort of betrayal about moving on in your life.

Tippett: Yeah. Right. Right.

Cave: That there’s some honor in just staying with the person who’s passed on.

Tippett: And even of remaining faithful to the love that you had for them.

Cave: Yeah. Yeah, that’s right. I think you can do both. You can move on and you can do things. I think you can turn your attention on to the world and in your own small way help other people in that respect, or help the world in some respect, whilst remaining true to the one that you lost. It’s not a zero-sum game. There’s no — I guess moving on is the wrong term, and the idea of closure is the wrong term.

Tippett: Yeah, I think that word is becoming discredited, even in psychology.

Cave: Okay, I’m glad to hear it. [laughs] Also, acceptance, I find, is not an ideal term either, because that, to me, feels like a returning to the way things were before. And I don’t think you do. I think, in fact, we just grow in magnitude that’s predicated on those we lose. It’s an amazing thing. I say this with a huge amount of caution, obviously, because I’d love it to be the way it was, actually, and just have my children, obviously, right?

Tippett: Yes.

Cave: But having said that, one feels an enormous and new capacity to love, I think. One can feel that way.

[music: “Ghosteen” by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds]

Tippett: There’s a phrase that comes up in the book, of “spiritual acceptance,” and you talk about poetic truth or metaphorical truth, that when something is true enough, it’s of real practical benefit. All of these things we’re talking about are in the realm of there being no definitive, right? There’s nothing to point at that is resolution or —

Cave: These are abstractions and—

Tippett: Right. Right.

Cave: In that respect, it’s extraordinarily difficult to argue your corner about these sorts of things against so-called rational, empirical truths about things. They have all the big guns. You just have a feeling or a softly spoken notion about these sorts of things. So, in a way, I’ve given up trying to — I think everyone who has the religious inclinations — I prefer to use the word religious rather than spiritual myself, but…

Tippett: Yeah. What did you say? “Religion is spirituality with rigor.”

Cave: Yeah, I just…

Tippett: I like that.

Cave: …feel it’s like a little — it’s asking something of us rather than, yeah, we’re all spiritual creatures, which of course we are. I’m more traditional too, in the sense that I find an acute feeling of the mystery of these matters in church. I know a lot of people have felt that it’s better to release God from the church and all of that stuff. I have found, in the last year or so, that this is a place that — I’ve actually found a church in the U.K., which I won’t mention which one it is because I just want to go there privately, that is cut off from the world. It feels no need to address the problems of the world. It’s a place that you go that it’s so beautiful. The singing is so beautiful. The music, the organ player’s off the charts, this character, in regard to just the pure drama of the narrative that plays out in the church service. It blows away my basic skeptical nature in a heartbeat. It allows me the permission to be deeply connected to those people that I’ve lost. That’s what it’s about, essentially.

By the time it gets to the communion it’s unbelievably moving, this service. In fact, this church has got a reputation of being the church for atheists, because it’s so beautiful that anyone can just feel these sorts of things.

Tippett: There’s the phrase, “spiritual, but not religious.” Something that I think is also coming back is “religious, but not spiritual,” which is what you…

Cave: Yeah, this is what…

Tippett: …represent.

Cave: It’s when I’m in a church that doesn’t know what it wants to do, where all my skepticism about whether God exists or, “What the hell am I doing in this place,” and all of that sort of stuff comes rushing in. I become personally embarrassed to be in this place. And so there’s something to be said for the sort of deeply, for all its flaws and all the rest of it, obviously, this sort of deeply traditional way of going about religion or navigating religion.

Tippett: Yes. And you might say, just referring back to something you said a minute ago, it’s religious institutions engaging in that conversation with rationality, defensively, and then losing the ground I stand on. And yet, just to go back to where we started, that what you learn in the thick of life is the limits of rationality. That this rational way of being that thinks and insists that we can plan everything, and that in fact we won’t again and again be obliterated by things that happened to us. It’s actually…

Cave: Well I don’t want to go into

Tippett: …it’s not reality.

Cave: I don’t want to go into a church to draw closer to the rational things in life.

Tippett: Right. Here’s something you said that I actually think would be very refreshing for a lot of people to hear. You said, this is again, in that dialogue with the rational, “Religion is a crutch, and a much-needed one.”

Cave: Right. Yeah. Well that’s true. And I have a lot of sympathy for people who use religion in that way. And I find it difficult to tolerate the argument that comes around kicking the crutches out from under people, but with their rationality. Because we need these things.

Tippett: Yeah, the reality is —

Cave: This is beyond whether God exists and stuff. But these matters. Now I have my own views that ebb and flow about that sort of thing. But at the same time, I’m not simply talking about that religion is useful in some rational way either. There’s some other thing that’s going on in religion that’s more important than that. But it is useful also that it does ameliorate that need to some degree of yearning that we’re talking about, or at least there’s something that we can reach toward.

[music: “Hollywood” by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds]

Tippett: So let’s talk about the mystery of music and songwriting. [laughter] I actually wanted to read you a poem. Would you like that? A Mary Oliver poem.

Cave: Who wrote this?

Tippett: Mary Oliver.

Cave: Oh, okay.

Tippett: Do you know her?

Cave: Yeah, yeah.

Tippett: Yeah.

I was enjoying everything: the rain, the path

wherever it was taking me, the earth roots

beginning to stir.

I didn’t intend to start thinking about God,

it just happened.

How God, or the gods, are invisible,

quite understandable.

But holiness is visible, entirely.

It’s wonderful to walk along like that,

thought not the usual intention to reach an answer

but merely drifting.

Like clouds that only seem weightless

but of course are not.

Are really important.

I mean, terribly important.

Not decoration by any means.

By next week the violets will be blooming.

Anyway, this was my delicious walk in the rain.

What was it actually about?

Think about what it is that music is trying to say.

It was something like that.

“Drifting” by Mary Oliver. Reprinted by the permission of The Charlotte Sheedy Literary Agency as agent for the author. Copyright © 2014, 2017 by Mary Oliver with permission of Bill Reichblum.

Cave: Okay. Well, that’s lovely.

[laughter]

Tippett: So: “what music is trying to say.” What does that evoke for you?

Cave: Well, okay, so…

Tippett: Of course the point of the poem is that you can’t sum that up, but I’m just curious about where Nick Cave’s mind goes.

Cave: Well you can’t really sum that up, but I can give it a go. And my feelings about this have changed, too, over the years. But it feels to me that music in itself, I would say, has a moral dimension. That it’s essentially good. That it works to improve matters. And that’s how I go about concerts these days. And it’s not me in particular, but any musician. In fact, playing any kind of music can do something to improve matters. There’s that.

And then there is of course, the sort of transcendent element, too, the communal element, the sort of outpouring, intaking, the sort of circular thing that goes on with an audience of love.

Tippett: Yeah. The way we now know that music actually syncs up breath and heartbeats, and it’s —

Cave: You mean communally?

Tippett: Yeah, communally. Yeah.

Cave: Yeah, that’s right. I mean, my concerts these days get quite wild in that respect. [laughs] And that’s why I spend so much time right up the front with the audience, because I can see them better. But to look into the face of a person that’s having a transcendent experience. It’s quite something, and especially en masse. I find that each time I’m playing and doing a concert, I feel that I’m doing something to help rehabilitate the world, or it’s a remedy for the world in some kind of way. And I don’t mean that in a high-blown kind of way…

Tippett: No, no. I know.

Cave: …in fact, to me, it’s like a small act of kindness too, in the way that we all have the opportunity to do. But there is also a mysterious and transcendent element to music.

Tippett: So I have to ask you —

Cave: That was an incredibly confused answer.

Tippett: No, it wasn’t at all. It was very clear. It was very clear. But I do have to ask, The Birthday Party band, which you were part of in your earlier life, which was at one point called “the most violent band in the world,” which I think was promotional. Is that…

Cave: It’s quite close to it.

Tippett: …is that also true even of that music?

Cave: Yeah, I think that we were always attempting in our way to find something that was — Yeah, yeah. Do I think it’s transcendent? Yes, I do. And very much so. And even though what I’m singing about is deeply problematic back then, I would say — to use that terrible word — even still I think it has this potential for doing good. And I just think we were looking for it in a different way. We were young and finding that sort of transcendent impulse in chaos. I didn’t look at things in that way at that time, but I can see that quite clearly.

Maybe my attitude at the time as a young teenage — I was a drug addicted young guy — that I had a kind of jaundiced, contemptuous view of the world. And that was the sort of default setting of my view of humanity. It was extreme, but it was also the way a lot of young people see the world, and in many ways from their perspective, quite rightly so.

Tippett: Here’s something you said in the book: “You only need ten songs, ten beautiful and breath-taking accidents to make up a record. You have to be patient and alert to the little miracles nestled in the ordinary.”

Cave: Okay. [laughs] Yeah, well, to get onto that, I mean, those ten songs, it seems kind of easy to do. But actually to get ten songs, to get ten miracles — of which, actually, only maybe three of them are actually miraculous and the other ones felt like they were at the time. But for me personally, it takes an enormous amount of — I have a particular kind of bizarre sort of work ethic where I get up and I sit down at nine o’clock in the morning and I start writing and I finish at 5:30, and I do it within office hours. And I try not to think creatively after that. If I have a muse, it has to keep office hours with me. Or my muse makes me keep office hours or something like that.

But essentially, every day, when I write a record I elect the day that I’m going to start writing it. I haven’t written anything for a couple of years. And I start to write a new record. And to arrive at those ten little miracles is actually extraordinarily difficult and full of all sorts of rather embarrassing kind of anxieties that my wife…

Tippett: Well that’s writing, that’s the creative process.

Cave: …rolls her eyes at, and I’m like, “It’s not coming, darling. It’s not coming.”

Tippett: Yeah.

Cave: She’s quite funny about that sort of thing. Not at all sympathetic. [laughs]

Tippett: Something else that you speak about is improvisation, which I feel like is such an important — is something that a musician can speak about, but actually it’s a life experience.

Cave: Yeah, it is. It is.

Tippett: So just a couple of things that you said, I’d love to — that improvisation is an act of acute vulnerability. And this I love, “the nature of improvisation is the coming together of two people with love — and a certain dissonance.”

Cave: Yeah. Well, that’s certainly the case with me and the guy I improvise with, Warren. It’s quite an extraordinary thing, and it’s a place where our relationship ignites and in quite a magical way. And I mean, we found that this is just a way we can write together, where you’re in the company of someone else — I don’t want to throw things out, it might be that two and two or more are gathered together or something like that. [laughter] Is it two or three? I can’t remember.

Tippett: I think it’s two or three.

Cave: Two or three…

Tippett: Yeah.

Cave: …are gathered together.

Tippett: I like that, yeah.

Cave: I am in your midst. That there’s something that certainly goes on in that respect.

Tippett: There’s a mystery to it.

Cave: Yeah, there is a mystery to it that we don’t talk about, we just do it. It’s an extraordinary thing because something happens where it makes conversation and these sorts of things meaningless. So we just create, then we sit and have lunch together and barely speak, and then we go in and do this stuff. So it’s this relationship that we have that’s extremely strong around this act of improvisation.

Tippett: I love that you also say “with love,” right? That there’s —

Cave: Yeah, yeah. Yes. It is an act of love. For each other as well

Tippett: And some of the energy of what transpires, certainly, is nourished by that, also, by that.

Cave: Yeah.

Tippett: And I mean just, there’s this mysterious thing also about the Skeleton Tree album that it seemed to be that you released it right after Arthur’s death, but it felt like an album that was —

Cave: Well, it was all written and recorded before he died.

Tippett: Written and recorded, and then even when people write about it, they write about it as the album you created after his death.

Cave: Yeah.

Tippett: And in fact, it was — you’ve talked about it — it was kind of foretelling the future in this —

Cave: I just feel essentially that songs seem to know more about what’s going on than you do. I don’t want to make too much of that you listen to it, and there’s these things that you can — It’s not like a kind of Beatles album that if you play it backwards, that speaks in tongues or something like that. There’s just something about that record that I felt had a dark energy of a particular kind that I felt extremely uncomfortable about. Especially after my son died, because we then had to go into the studio and mix it. And these songs seemed to be speaking deeply into that in a very disconcerting way at the time. I find that to be quite a difficult record to listen to. Not that I really listen to my own stuff, but that record in particular.

The record after that, Ghosteen, is something that’s directly — it’s essentially made, certainly when I was making it I was attempting, in some way, to reach out to Arthur. In what way I’m not quite sure.

This is a strange thing to talk about. I find it very difficult to articulate. But at the time to somehow attempt to, well, it was to ask forgiveness in some kind of way for what had happened with Arthur.

Tippett: Of him?

Cave: In the sense that I had sort of residual feelings of guilt and these sorts of things that I think parents tend to do if they’ve lost a child.

Tippett: Mm-hmm.

Cave: And to sort of help his condition, that was the thing that was going through my mind at the time. And to do something other than just burying him. And I love that record Ghosteen, because I think we managed to do something that was very beautiful in that respect.

[music: “Ghosteen” by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds]

Tippett: It’s kind of a mythical narrative, almost. But you said it “became an imagined world where Arthur could be.”

Cave: Yeah. Yeah, that’s a lovely way to put it. [laughter]

Tippett: Good job. You said, he’s running around inside the songs.

Cave: Oh, did I say that?

Tippett: Yeah, it’s in the book. But did you feel that when you were writing it, or was it after you had produced it?

Cave: No, I felt that — there were lots that were going on when I was making that record. There was a desperation that was going on behind the record, and just to make sense of things. And that record, weirdly, went some way of making sense of something; that I could do something tangible in his, not just in his memory, but for him as a sort of — it’s too difficult for me to — but for him. To somehow help his spiritual condition, even though I know that that sounds sort of crazy, at the time it didn’t.

Tippett: It doesn’t sound crazy unless you think there’s nothing, no such thing as mystery.

Cave: Yeah, okay, okay.

Tippett: Right.

Cave: Well, at the time of making that, I mean, I don’t know about these matters.

Tippett: Right, and no one does.

Cave: And so I can’t argue one way or other about those sorts of things. But we have intuitions and I think that they were highly — at the time I was very responsive to that sort of thing.

Tippett: And in that, somewhere you talked about, you said songs have an essential self. And there’s this song, the track on that album, “Ghosteen Speaks.”

Cave: Yeah.

Tippett: And then there’s also the Seven Psalms you’ve done, right?

Cave: Yeah.

Tippett: There’s almost a way in which, and with the “Ghosteen Speaks,” you said that that one just condensed into a mantra, condensed into a prayer.

Cave: Yeah.

Tippett: There’s a liturgical quality to some of the music you do now, which seems to me, it makes sense as a reflection of the fullness of this experience that you’ve been having, of being alive in these last years.

Cave: The “Ghosteen Speaks” started as a massive thing, and it just kept getting smaller and smaller until I think it’s pretty much, “I am beside you. Look for me.” That’s essentially what it is over and over again.

[music: “Ghosteen Speaks” by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds]

Cave: That song is essentially from his point of view, that “I am beside you.”

Tippett: That he is beside you.

Cave: Yeah. “Look for me.”

Tippett: Yes.

[music: “Ghosteen Speaks” by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds]

Cave: As with a lot of our improvised material, it is improvised over chordal patterns that I don’t know exactly what’s going on, because we’re playing together at the same time. And so these words sometimes feel like they come from other places. It certainly did at the time.

[music: “Ghosteen Speaks” by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds]

Tippett: This feels to me like it — wrapping back around to the limits of the rational and how hard it is to speak of the mysterious — but you said, I love this, but you said, “There is no problem of evil. There is only a problem of good.”

Cave: It’s the audacity of the world to continue to be beautiful and continue to be good in times of deep suffering. That’s how I saw the world. It was sort of not paying me any attention. It was just carrying on, being systemically gorgeous. [laughter] And how dare it? But there you have it.

I get letters, too, from people who write into The Red Hand Files, who are furious with the way I talk about these sorts of things. “How can you?” They’re so ruined by loss, and they see that I’m sort of putting a positive spin on their agony.

And I understand that, too. But I think it’s not just me, I think it’s everything that’s happening around them, that life goes on and the sun still rises, and the birds sit in the trees and all the rest of it. And there feels like it’s almost an act of kind of cosmic betrayal for this to be going on.

Tippett: Right.

Cave: Because people are suffering so deeply. And that’s one thing I try and say is that — because we’ve already spoken about this — but the temptation is to cling on to that absence. To sort of fold yourself around the lack of something, rather than turning yourself out and looking at the world in that kind of way and coming to terms with that. It’s dangerous. It can become like a hardening of the soul around this disappearance of something. And that’s not good. I try not to tell people what to do about things, but that’s one thing I think that grieving people need to be careful about.

Tippett: Mm-hmm. I think we’ve touched on this, or I just want to kind of land here also, that we live in this age where the pandemic was an extraordinary experience. The pain of that is still with us, the rupture of that is still with us. We really did have a collective, have had a collective moment of loss. And then this phrase: ecological grief. We are all experiencing rupture in this beautiful planet, that is, which we are of, not in. And so I feel like there is — sorry, go on.

Cave: Do you think that — did you feel that the pandemic offered us an opportunity?

Tippett: I did.

Cave: And that we squandered that opportunity, or that we —?

Tippett: I have felt that. I guess I try to take a longer view of time and say that it might still happen, and that it’s happening, perhaps, in ways that are hard to chart.

Cave: Yeah, exactly, beautifully put. And I feel that too, in some kind of way. Even though the world ruptured further, it wasn’t a great bringing together in any way.

Tippett: No, no.

Cave: I think it has sort of focused some people’s needs in a different way.

Tippett: Right.

Cave: It’s a difficult thing to talk about. But I’ve just noticed with people that they feel more attentive to things, spiritual matters…

Tippett: I’m feeling that, too.

Cave: …for want of a better word.

Tippett: No, that people are really ready to go to places.

Cave: I never use that word, by the way. [laughs]

Tippett: No, I don’t either. I don’t either. But that word itself used to be anathema.

Cave: Yeah.

Tippett: And not in this unrigorous way that you and I — [laughs]

Cave: Yes, yes. I meant to say this, that five years ago if I’d sat down at the dinner table and talked about going to church, I’d be laughed out of the room, essentially. I don’t know, maybe you sit around with different people. But these days there is a weird kind of curiosity around those sorts of things, that it’s not seen in the same way. And there might be a whole lot of different reasons. But I feel that the pandemic and the other things that you’re talking about, too, are igniting these concerns in people, in some people.

Tippett: I mean, you had this lovely sentence in the book also, you said you perceived a — I love this image — a “subterranean undertow of concern and connectivity…towards a more empathic and enhanced existence.” And I experienced that too. It’s not the whole picture…

Cave: It’s not the whole picture.

Tippett: …it’s not what gets reported, but it seems to be quietly rising up.

Cave: Well, I think that goes back to what we were talking about at the start, the recognition of our common condition, which is loss. Now, I know a lot of people will react very badly to that. But on top of that, there’s all sorts of other things that are going on within, but I think that that is the sort of bedrock that we recognized on some level.

Tippett: I really do see you as a poet. Do you see yourself as a poet, as a songwriter?

Cave: Not really.

Tippett: Not really?

Cave: [laughs] Well, I don’t. I’m still kind of — I feel I’m a songwriter.

Tippett: Yeah.

Cave: When people say, “I think you’re a poet,” it often feels like they’re suggesting that, for some reason, poetry is an elevated form of songwriting. And I’m very proud to be a songwriter.

Tippett: Oh, I think they’re the same thing, right? Aren’t they just the same thing?

Cave: Yeah. Well, I guess —

Tippett: I think songs are the primary way that humans alive today imbibe poetry without realizing, perhaps thinking that poetry isn’t part of their lives.

Cave: My father was an English literature teacher, and he had his views on what poetry was and what poetry wasn’t. [laughs]

Tippett: He probably wouldn’t have agreed with Bob Dylan getting the Nobel.

Cave: Well, I don’t know, but he certainly didn’t — he saw Shakespeare sitting up there at the top of everything. And I still very much hear him sort of gnashing his teeth whenever I talk about this sort of thing.

Tippett: So this song, “Anthropocene,” though, to me seems —

Cave: It’s actually “Anthrocene,” I did a sort of bastardization of the —

Tippett: Oh, I thought it was misspelled.

Cave: No, no, it’s not.

Tippett: I thought it was being misspelled. I went through and spell corrected it “Anthrocene.” [laughs]

Cave: No, no, no. It’s actually called “Anthrocene.”

Tippett: Would you entertain the idea of reading this? No?

Cave: I wouldn’t like to read that one because I don’t think the lyrics are very good, as a poem.

Tippett: Well, can I just read the last two lines that feel that they speak to our world now?

Cave: Okay. Go on, go for it.

Tippett: “Here they come now! Here they come, pulling you away

There are powers at play more forceful than we

Come over here and sit down and say a short prayer

A prayer to the air! To the air that we breathe!

And the astonishing rise of the Anthrocene

Come on now! Come on now

Hold your breath while you say

It’s a long way back and I’m begging you please

To come home now. Come home now

I heard you’ve been out looking for something to love

Close your eyes, little world, and brace yourself.”

Cave: Oh yeah. That’s pretty good, right?

Tippett: It’s pretty good.

Cave: Wow. What a great song. [laughs]

Tippett: You want to read those last, will you read it?

Cave: Okay. Okay.

“Here they come now! Here they come, pulling you away

There are powers at play more forceful than we

Come over here and sit down and say a short prayer

A prayer to the air! To the air that we breathe!

And the astonishing rise of the Anthrocene

Come on now! Come on now!

Hold your breath while you say

It’s a long way back and I’m begging you please

To come home now. Come home now

[I’ve] heard you’ve been out looking for something to love

Close your eyes, little world, and brace yourself.”

[music: “Anthrocene” by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds]

Cave: Well, that’s awesome.

Tippett: It’s awesome. Thank you so much. Thank you so much for what you do and how you’ve opened yourself to being present to everybody else with what you carry, and for making your trip to our studio. Thank you so much.

Cave: Yeah, I’ve really enjoyed it. It’s lovely, lovely. Thank you very much.

Tippett: Yeah, it’s been beautiful.

[music: “Galleon Ship” by Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds]

Nick Cave is the songwriter and lead singer of Nick Cave and The Bad Seeds. Their albums include Ghosteen, Skeleton Tree, and Push The Sky Away. His recent albums with frequent collaborator Warren Ellis include Seven Psalms and Carnage. His book, which takes the form of an electric conversation with journalist Seán O’Hagan, is Faith, Hope and Carnage. Nick frequently writes, and answers questions from his fans, on the website, The Red Hand Files.

[music: “Eventide” by Gautam Srikishan]

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Laurén Drommerhausen, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Gautam Srikishan, April Adamson, Ashley Her, Amy Chatelaine, Cameron Mussar, Kayla Edwards, Tiffany Champion, Juliette Dallas-Feeney, Annisa Hale, and Andrea Prevost.

Special, special thanks to AWAL, BMG and Kobalt Music Group for permission to use the music in this episode.

And to Penguin Press, for permission to read Mary Oliver’s poem, “Drifting,” which is published in the collection, Devotions: The Selected Poems of Mary Oliver.

On Being is an independent nonprofit production of The On Being Project. We are located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. Our closing music was composed by Gautam Srikishan. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

Our funding partners include:

The Hearthland Foundation. Helping to build a more just, equitable and connected America — one creative act at a time.

The Fetzer Institute, supporting a movement of organizations applying spiritual solutions to society’s toughest problems. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation. Dedicated to cultivating the connections between ecology, culture, and spirituality. Supporting initiatives and organizations that uphold sacred relationships with the living Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org.

The Osprey Foundation — a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives.

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.

Reflections