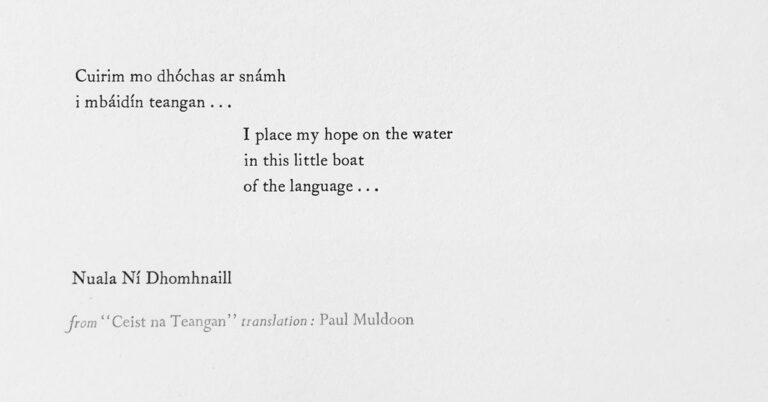

Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill

Ceist na Teangan (The Language Issue)

Are there languages that once were spoken in your family that are not anymore? What caused those changes?

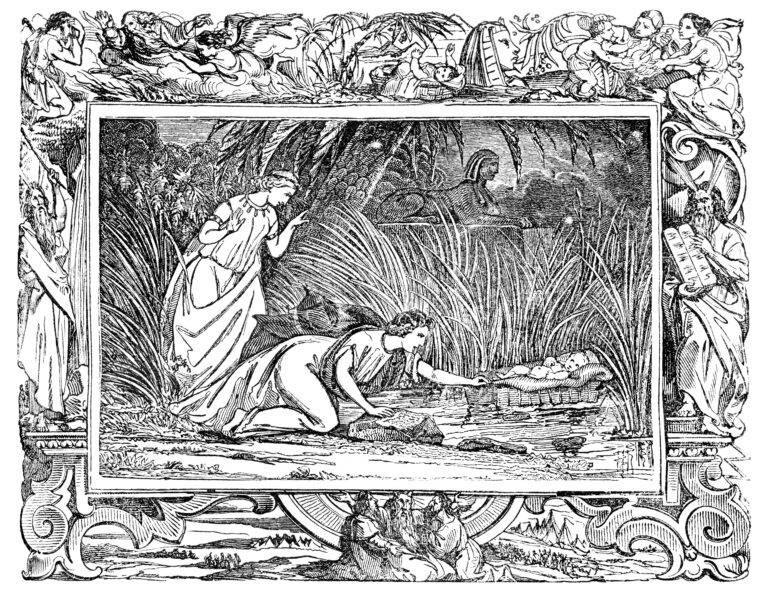

This poem considers the plight of a language, how it — like the child Moses in the biblical story of the Exodus — is vulnerable, and might be in need of someone like the Pharaoh’s daughter to nurture it. In considering the precarious situation of many lesser-spoken languages, Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill casts a story of language preservation through the archetype of women helping women in ancient texts.

Image by Expedition Press/Expedition Press, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill is one of the most prominent poets writing in the Irish language today. Her poetry collections include Pharaoh’s Daughter, The Astrakhan Cloak, and Cead Isteach/Entry Permitted. Her work has been translated into English by a number of well-known Irish poets, including Seamus Heaney, Medbh McGuckian, and Paul Muldoon.

Transcript

Pádraig Ó Tuama, host: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and the dialect of Irish that I speak is the Munster Irish and maybe, specifically, the Cork and Kerry Irish. And other Irish language speakers around the country laugh at us because we tend to overemphasize these long vowel sounds. But that’s what I’ve always loved about poetry, is long vowel sounds create music and listening. And much and all as, initially, when I moved up north and people were laughing at the way I speak Irish, I’m now very proud of that. And I speak my own dialect with great joy and engage in happy banter about why I think it’s better to over-pronounce long vowels.

[music: “Ashed to Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: Today’s poem is by the Irish language poet Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill. And it’s called Ceist na Teangan. And I’ll read it in Irish and in English.

“Ceist na Teangan” by Nuala NÍ Dhomhnaill:

“Cuirim mo dhóchas ar snámh

i mbáidín teangan

faoi mar a leagfá naíonán

i gcliabhán

a bheadh fite fuaite

de dhuilleoga feileastraim

is bitiúmin agus pic

bheith cuimilte lena thóin

ansan é a leagadh síos

i measc na ngiolcach

is coigeal na mban sí

le taobh na habhann,

féachaint n’fheadaraís

cá dtabharfaidh an sruth é,

féachaint, dála Mhaoise,

an bhfóirfidh iníon Fharoinn?”

“The Language Issue” by Nuala NÍ Dhomhnaill, translated by Paul Muldoon:

“I place my hope on the water

in this little boat

of the language, the way a body might put

an infant

in a basket of intertwined

iris leaves,

its underside proofed

with bitumen and pitch,

then set the whole thing down amidst

the sedge

and bulrushes by the edge

of a river

only to have it borne hither and thither,

not knowing where it might end up;

in the lap, perhaps,

of some Pharaoh’s daughter.”

[music: “Ashed to Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill wrote, when she was Ireland professor of poetry, she wrote that she lives with the reality that she speaks and writes in a language that might be dead before she is. And that is such brutal talk. In the ’70s and ’80s, she was considered one of the Irish language revival poets — there was a whole troupe of them, brilliant, brilliant poets, who she said sometimes were in competition with each other. And they were wanting to write in Irish about sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll, so they were wanting to bring this old language into speaking about very contemporary things.

And the knife edge on which languages like Irish dwell is a really careful knife edge, because it’s so dear in the hearts of people, but, so often, in policy and in provision, and in education, too, that language might suffer from neglect. And so I see this delicate, delicate image that she has — a powerful image, as well as delicate — of a woman wishing for a language to live, knowing that she mightn’t be the one to be able to make it live. And she, like the mother of Moses, places this language in a basket and sets it afloat on a river, hoping that it might be picked up by the daughter of an enemy and that that picking up might be something that helps it revive.

And I just think that that image is such a powerful one and is such a different kind of image that you see in comparison to so many other ways of speaking about language preservation. There is reciprocality here. There’s an old reference to enmity, in this poem, and, similarly, this poem is a poem that dwells in the economy of women. And Irish language poetry has so often been dominated by the voices of men, and not only Irish language poetry, but English language poetry from Ireland; so many of the names that are known internationally are the names of Seamus Heaney or Yeats or Kavanagh. And Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill is making a point about gender and language, as well as a point of endangered indigenous languages, like the Irish language here.

[music: “First Grief, First Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: Up until the 1800s the Irish language was the absolute lingua franca of Ireland all across. And then, the famine from the 1840s, certainly, was exploited for political gain in terms of economy, as well as in language. But there has been a long history in so many parts of the world, where language has been used as a weapon. From the 1300s, it was illegal for Irish people to speak in Irish to English people, when those English people were in Ireland. And, from the 1500s, that language was made illegal in the Parliament, as well as in certain places around the country. From the 1700s, the usage of Irish in the courts and legal documents was criminalized, bringing a fine. And then, in the late 1800s, when people were bereft and falling apart, because of the impact of that awful famine, it was Irish Protestant people who were involved in a revival of the Irish language. And so often, the history of the Irish language is spoken about as if it is a Catholic language, against the Protestant population of Ireland, and that’s so untrue. It’s a language that’s owned by so many.

I heard Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill interviewed once, and somebody had been saying to her, “Where’s your home?” because she was born in England of Irish parents, and then, at the age of five, she was sent back to Ireland to be brought up by an aunt in County Kerry in an Irish-speaking area. And she said that when she thinks about home, she thinks about the Irish language — that the Irish language is her home. And so I do feel like this poem is one of the summative poems of her life. She’s written many: she’s a prolific and brilliant poet. But I always come back to this one, and love it dearly.

Ó Tuama: It’s hard for me to imagine my life without the layer of the Irish language. While I operate 99.9% of the time in English, I’m always, at some point during the day, thinking about how would I say that in Irish? What’s the context of saying that in Irish? Or I’m talking to myself in Irish. The other week, a robin came into the house and was trapped inside the house. And I went to try and free the robin out through a window. And it was only after I’d gotten the robin out that I realized I’d been speaking to the robin in Irish; that it was a language of consolation, it was language of tenderness. Even though Irish can say harsh things, nonetheless, for me, it’s a language that holds something of the heart in it.

The Irish language doesn’t have a particular word for yes or no. If you ask me a question, and I want to say no, I’ll have to respond with the verb of that question. So if you say, “Are you coming to the party?” I can’t say, “Yeah.” I’d have to say, “Yeah, I’m coming to the party” or “No, I’m not.” And I love that, that there’s a courtesy of paying attention to the verb that’s used in a question; that you have to conjugate that verb in the reply.

I think that’s influenced the way that Irish people go about conflict, as well. It’s influenced our joy. It’s influenced our sadness. The Irish language doesn’t have a verb for love, and so, instead, we’ve had to find ways around that constraint. And so one of the ways of saying that you love a person, particularly romantic, deep, erotic love, is to say to them, “Mo cheol thú” — “You are my music.” And that’s a way of getting around the constraints, where there isn’t a formal verb for something, and nonetheless finding a new way, with the poetry indigenous to the tongue, to say the very thing that you mean.

[music: “The House You Wake In” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: I think this poem invites us into both grief and hope: grief for languages that are endangered or are put under a spotlight or are used as a football by people who want to suppress them; and then it also brings into us the possibility of hope that there are ways in which language will survive. And it is Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill, as a person who has worked in the Irish language her whole life, and her professional life has been so much about the Irish language revival and using it so well, it’s her saying she knows that she won’t be the final one to save it, but that there might be some element of hope, there might be some element of surprise, there might be something new that nonetheless picks up an old story that might bring about a revival and a safety of that language.

[music: “Into the Earth” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Ceist na Teangan” by Nuala NÍ Dhomhnaill:

“Cuirim mo dhóchas ar snámh

i mbáidín teangan

faoi mar a leagfá naíonán

i gcliabhán

a bheadh fite fuaite

de dhuilleoga feileastraim

is bitiúmin agus pic

bheith cuimilte lena thóin

ansan é a leagadh síos

i measc na ngiolcach

is coigeal na mban sí

le taobh na habhann,

féachaint n’fheadaraís

cá dtabharfaidh an sruth é,

féachaint, dála Mhaoise,

an bhfóirfidh iníon Fharoinn?”

“The Language Issue” by Nuala NÍ Dhomhnaill, translated by Paul Muldoon:

“I place my hope on the water

in this little boat

of the language, the way a body might put

an infant

in a basket of intertwined

iris leaves,

its underside proofed

with bitumen and pitch,

then setting the whole thing down amidst

the sedge

and bulrushes by the edge

of a river

only to have it borne hither and thither,

not knowing where it might end up;

in the lap, perhaps,

of some Pharaoh’s daughter.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Lily Percy: Ceist na Teangan (The Language Issue)” comes from Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill’s book, Pharaoh’s Daughter. Thank you to The Gallery Press who gave us permission to use Nuala’s poem. You can find a link to the poem in our show notes, along with Pádraig’s guiding question for this episode.

Poetry Unbound is Chris Heagle, Erin Colasacco, Serri Graslie, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Christiane Wartell, Karen Navarre, Karyn Towey, Sue Ariza, and me, Lily Percy. Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions. This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. We also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me — find those wherever you like to listen or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.