Ofelia Zepeda

Deer Dance Exhibition

Most of us do our eavesdropping shyly and secretively, but Ofelia Zepeda’s poem “Deer Dance Exhibition” welcomes us to listen in on an exchange between people as they watch a ceremonial dance. Along the way, we get the sense that what we’re witnessing is more than a conversation — it’s the sounds and sensations of life itself.

We’re pleased to offer Ofelia Zepeda’s poem, and invite you to read Pádraig’s weekly Poetry Unbound Substack, read the Poetry Unbound book, or listen back to all our episodes.

Image by Annisa Hale/ Film processed by Moody's Film Lab, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

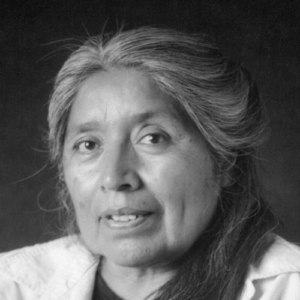

Ofelia Zepeda is a poet, Regents Professor of Linguistics at the University of Arizona, and the recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship for her work in American Indian language education. She is the current editor of Sun Tracks, launched in 1971 and one of the first publishing programs to focus exclusively on the creative works of Native Americans. Her current poetry books include: Ocean Power: Poems from the Desert (The University of Arizona Press, 1995), Jewed ‘I-hoi/ Earth Movements (Kore Press, 2005), and Where Clouds are Formed (The University of Arizona Press, 2008). Image by Tony Celentano.

Transcript

Transcription by Alletta Cooper

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and I love form and poetry — sonnets or villanelle or pantoum, and some of those might be considered to be traditional. But we’re always working in forms today in so many of the ways that we write: a text message, a recipe, an instruction manual, a sign telling you where to go, a newspaper ad, or a dating profile. All of those are forms of writing that we engage with. We have ideas about what it should be in order to make it comprehensible or good or useful. And I love it when poetry uses these as ways to engage, as well as some of the older, more traditional forms.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Deer Dance Exhibition” by Ofelia Zepeda

“Question: Can you tell us about what he is wearing?

Well, the hooves represent the deer’s hooves,

the red scarf represents the flowers from which he ate,

the shawl is for the skin.

The cocoons make the sound of the deer walking on leaves and grass.

Listen.

Question: What is that he is beating on?

It’s a gourd drum. The drum represents the heartbeat of the deer.

Listen.

When the drum beats, it brings the deer to life.

We believe the water the drum sits in is holy. It is life.

Go ahead, touch it.

Bless yourself with it.

It is holy. You are safe now.

Question: How does the boy become a dancer?

He just knows. His mother said he had dreams when he was just a little boy.

You know how that happens. He just had it in him.

Then he started working with older men who taught him how to dance.

He has made many sacrifices for his dancing even for just a young boy.

The people concur, “Yes, you can see it in his face.”

Question: What do they do with the money we throw them?

Oh, they just split it among the singers and dancer.

They will probably take the boy to McDonald’s for a burger and fries.

The men will probably have a cold one.

It’s hot today, you know.”

[music: “Keeping Up” by Blue Dot Sessions]

This poem, “Deer Dance Exhibition” by Ofelia Zepeda is in the form of Q and A, back and forth, four questions and then replies to those questions. Q and A is a very powerful kind of form. It happens very naturally in conversations between people, somebody who knows something and somebody else who is wanting to ask very specific questions, and this is what Ofelia Zepeda is representing on the page here. It seems to me like the one who’s responding is a single voice that’s speaking, but the one who’s asking the question is, perhaps, a representative voice. It might be a crowd of people who are asking questions of one single responder. And the questioner asks four questions. “Can you tell us about what he’s wearing?” “What is that he’s beating on?” “How does the boy become a dancer?” and “What do they do with the money we throw them?” So with this, there’s the story of a garment and information about the percussion instrument and the backstory of the dancer, and then the question about what comes after. There are questions about what can be seen and who can be seen. Questions about money, culture and representation, and meaning, and musicality, and craft are in there, too, as well as education and a sense of vocation and a sense of the role within that as a community.

There is, underneath all of that, too, the recognition between the two voices represented in this poem of being like and unalike; of knowledge not shared, and knowledge shared, as well as something undergirding that that draws them together. There is reciprocality between these two. There is something that holds them together even when knowledge separates.

[music: “Sticktop” by Blue Dot Sessions]

In one way, while this entire poem is written in English, there is nonetheless a translation or interpretation that’s happening between these two voices — the person asking questions and the person answering. There’s all kinds of theories about translation: to be as exact to the original meaning as possible if you’re translating a poem, or to translate in a way where the sense or the feeling is communicated. And other times what you’re trying to do is to create ways within the web of meaning that is part of one language or one cultural expression is translated into a corresponding, but perhaps quite different, web of meaning in the cultural experience or the language into which it’s been translated or interpreted.

This poem here corresponds enormously to what it’s like to consider how it is that we should explore and navigate the territory of interpretation and translation when there is a lack of knowledge — not necessarily about language, in this poem, but about what am I seeing, what is right in front of me? And some of the answers at the start are very definitely about what’s right in front of me. “Can you tell us about what he’s wearing?” And then there’s the description of the hooves and what they represent, the deer’s hooves and the scarf representing the flowers from which the deer ate, and the shawl for the skin, and the cocoons for the sound of the deer. And then there’s the question about the gourd drum representing the heart of the deer and what that does. And then an invitation to experience, not just to observe, not just to comprehend, but to participate.

Each response that the respondee gives in this poem is inviting a deeper engagement. By the third question, there’s a sense to say, well, your intuition probably has guessed that this is true. “You know how that happens.” And then by the fourth, there’s great humor. There’s the sense of going, yeah, I mean, the boy will want a burger and fries and the men will probably get a cold one. “It’s hot today you know.” Each response is doing different work about observation, about comprehension, about participation, about shared knowledge, and also about just saying, “Well, yeah, but just look around. Look at where we are. It’s hot. Who doesn’t want a cold one?”

[music: “Spindash” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Part of the reason why I’m so interested in looking at this poem through the lens of interpretation or translation as something that happens all the time is knowing a small bit about the poet, Ofelia Zepeda. She’s a member of the Tohono O’odham Nation, and she’s a professor of linguistics and is the author of a grammar book on Tohono O’odham language. The book in which this poem is collected is called Ocean Power, and some of these poems are written in the O’odham language, and of the ones that are, some of those are translated and others aren’t.

Tohono O’odham means “desert people” and the Tohono O’odham Nation is around what is now considered the international border between the U.S. and Mexico. The deer dance is a dance of the Mayo and Yaqui peoples who are neighboring nations of the Tohono O’odham Nation. Many other cultures do have deer dance traditions, also with different interpretations and different meanings.

There’s twice in the poem where “listen” is a single-word sentence in response to the questioner. The “listen” of the poem is not only the voice of the responders speaking to the questioner, it’s also the voice of the poem speaking to us who are reading or listening to the poem. “Listen” and what we can hear is the hooves that represent the deer’s hooves, and the cocoons that make the sound of the deer walking on leaves and grass, and the drum representing the heartbeat. “When the drum beats, it brings the deer to life.” What is brought to life in me when I hear the sound of this through the page, through the lyric, through the voice reading the poem? What do I listen to? This poem is reaching out through the very specific dialogue between two people and inviting anybody who’s engaging with the poem to listen to the acoustics of their own life and what’s around them.

[music: “At Dusk” by Gautam Srikishan]

The poem is operating on so many levels. Of course, there’s the two people talking, but the two people talking are watching something else. They’re watching what is the title of the poem, “Deer Dance Exhibition.” And in response to that, there’s question and answer, seeking for understanding. But then, on another level, too, there’s these reassurances throughout the poem. “You know how that happens? He just had it in him,” is one of those, and then “the people concur, ‘Yes, you can see it in his face.’” And then the “you know” — “it’s hot today you know.” Even the casual nature within which this final line occurs. “You know,” there, is doing so much work. It’s the generosity and the hospitality of the responding voice throughout this poem, to create a sense of we have something shared in us alongside what is not comprehended.

Alongside all the reassurances, is this sharing of life. “We believe the water the drum sits in is holy. It is life. / Go ahead, touch it. / Bless yourself with it. / It is holy. You are safe now.” To be brought into the shared ritual, to be brought into a container that can hold water, that can share life, that is the symbol of holiness, that is holiness. This, I think, is another demonstration of the reciprocality of shared life in the poem. And it is the capacity of the poem to hold these together with benevolence that is of such interest to me.

Depending as to how you interpret it — and I don’t know how to interpret it. I’ve thought about this, and I think all I can offer is my ignorance — regarding the word “exhibition” at the end of “Deer Dance Exhibition.” All I can bring is a very Irish way of reading exhibition, feeling perhaps a little bit uncomfortable about it. But the tone of response from the responder’s voice in the poem with all of these reassurances, it seems like what they’re watching is drawing them into a conversation that goes ever deeper and ever deeper, where there’s a mutual recognition of each other and a reassurance that’s happening coming from, especially, the voice of the responder.

[music: “The Consulate” by Blue Dot Sessions]

“Deer Dance Exhibition” by Ofelia Zepeda

“Question: Can you tell us about what he is wearing?

Well, the hooves represent the deer’s hooves,

the red scarf represents the flowers from which he ate,

the shawl is for the skin.

The cocoons make the sound of the deer walking on leaves and grass.

Listen.

Question: What is that he is beating on?

It’s a gourd drum. The drum represents the heartbeat of the deer.

Listen.

When the drum beats, it brings the deer to life.

We believe the water the drum sits in is holy. It is life.

Go ahead, touch it.

Bless yourself with it.

It is holy. You are safe now.

Question: How does the boy become a dancer?

He just knows. His mother said he had dreams when he was just a little boy.

You know how that happens. He just had it in him.

Then he started working with older men who taught him how to dance.

He has made many sacrifices for his dancing even for just a young boy.

The people concur, “Yes, you can see it in his face.”

Question: What do they do with the money we throw them?

Oh, they just split it among the singers and dancer.

They will probably take the boy to McDonald’s for a burger and fries.

The men will probably have a cold one.

It’s hot today, you know.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Chris Heagle: “Deer Dance Exhibition” comes from Ofelia Zepeda’s book Ocean Power. Thank you to university of Arizona Press who gave us permission to use Ofelia’s poem. Read it on our website at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Amy Chatelaine, Kayla Edwards, Annisa Hale, and me, Chris Heagle.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions.

This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. Open your world to poetry with us by subscribing to our Substack newsletter. You may also enjoy Pádraig’s book, Poetry Unbound: Fifty Poems to Open Your World. For links and to find out more visit poetryunbound.org.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.