Paul Raushenbush

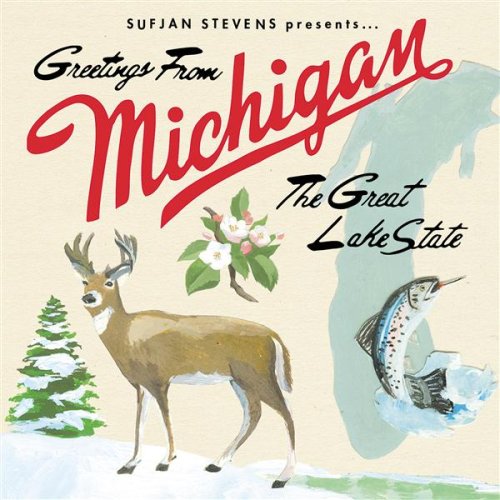

Occupying the Gospel

Paul Brandeis Raushenbush opens up a hidden but possibly re-emerging influence in the DNA of American Christianity, reaching back to the Social Gospel movement at the turn of the 20th century. And, the Huffington Post religion editor shares what he’s learning about religion in this century’s evolving realm of technology.

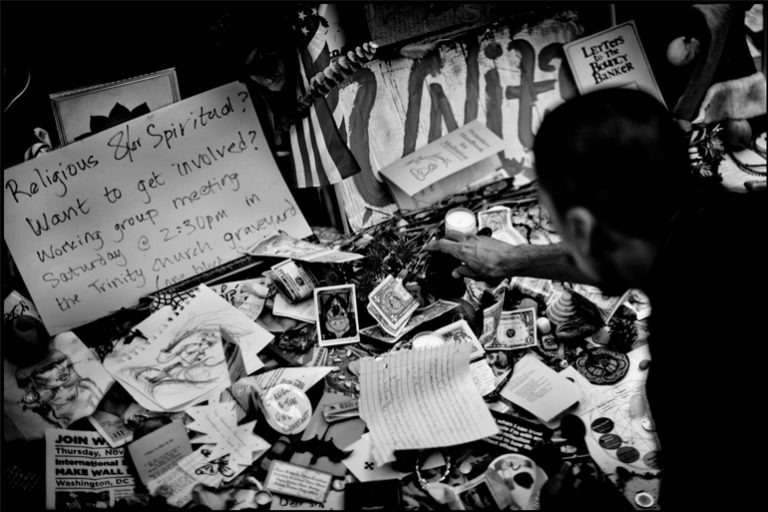

Image by Zoriah/Flickr, Attribution-NonCommercial.

Guest

Paul Raushenbush is a writer, editor, and religious activist. He currently serves as Senior Vice-President for Public Engagement at Auburn Seminary and was the Executive Editor Of Global Spirituality and Religion for Huffington Post's Religion section, and formerly served as editor of BeliefNet. Raushenbush served as Associate Dean of Religious Life and the Chapel at Princeton University and is an ordained Baptist minister in the American Baptist tradition. He is a graduate of Macalester College and Union Theological Seminary. He currently lives in New York and is married to the author Brad Gooch.

Transcript

November 17, 2011

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: From Occupy Wall Street to the National Association of Evangelicals, there are echoes of what was called the Social Gospel a hundred years ago. This movement coined the phrase, “What Would Jesus Do?” And for three years running, its pivotal text by its leading figure, Walter Rauschenbusch, sold more copies than any religious book after the Bible. Rauschenbusch called for Christians to be at the forefront of social renewal, healing that era’s social crisis. But his subject headings alone sound oddly present: The Morale of the Workers; The Physical Decline of the People; The Wedge of Inequality.

Fast-forward to today, and Walter Rauschenbusch’s great-grandson, Paul Raushenbush, is the religion editor of the Huffington Post. We have some fun this hour. We learn some things, about reemerging strains in the DNA of Christianity. And we take in a counterintuitive view of religion and culture from an emerging realm of our time. Paul Raushenbush likes to recall a complaint from a blogger named “grumpy” to one of his posts on the Huffington Post: “Now I have seen it all, the Huff post asking what would be the correct thing to do from a religious standpoint. … I cannot believe I am seeing this on the Huff post.” Paul Raushenbush replied, “Well, grumpy — believe it.”

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: People are surprised, but that’s my standard line: “This is good, but it could be a little more religion-y” (laughter). And by religion-y, I just mean go deep into your tradition. Don’t be shy about it.

MS. TIPPETT: From APM, American Public Media, I’m Krista Tippett. Today, On Being: “Occupying the Gospel.”

Paul Brandeis Raushenbush has been Senior Religion Editor of the Huffington Post since that section’s launch in 2010. He also spent nine years as chaplain and Associate Dean of Religious Life at Princeton University. He grew up in Madison, Wisconsin, where Walter Rauschenbusch’s son settled with his wife, who happened to be the daughter of Louis Brandeis, the first Jewish Supreme Court Justice. Despite his noble lineage, Paul says, he only distinguished himself religiously in his early years by being the first person to flunk out of Presbyterian confirmation.

And you, of course, had in your DNA and in your family history this great American Christian religious figure of Walter Rauschenbusch. How aware of that were you of him? How did you become aware of him growing up?

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: You know, we really weren’t particularly aware of him. I think we may have said one of his prayers at Thanksgiving. He has beautiful prayers. If people are interested in Walter Rauschenbusch, they should first go to the prayers because they really are the right door to understanding who he was. So he had a beautiful Thanksgiving prayer that we would read on Thanksgiving or occasionally at grace. But, you know, my parents were very reluctant to kind of get into, well, you have this important great-grandfather or …

MS. TIPPETT: You also had two important great-grandfathers, right? The other one, Justice Brandeis?

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Yeah. Brandeis was actually much more the kind of overwhelming figure, and I knew much more about Brandeis than I did Rauschenbusch. It was only later actually in seminary and even beyond when I started to read Rauschenbusch and really began to actually resonate with what his message was and found myself just loving his writing style and what he had to say and he felt so fresh and contemporary and funny and heart-rending. So that’s when I really began to realize that actually I kind of had a kindred spirit with him. But it really wasn’t a part of growing up. You know, Rauschenbusch was in the background.

MS. TIPPETT: So let’s talk about this person of Walter Rauschenbusch because he really was a very important figure in the very early 20th century. You know, he was an exemplar and a very strong voice in the roots of American Protestantism and indeed what called itself Evangelicalism that were socially activists, this Social Gospel movement that people roughly date between something like 1880 and 1920. Say something about that — that world that he helped create and that he came out of.

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Well, talking about the world he came out of is really important because Walter was the seventh generation of pastors who — his father came over as a Lutheran missionary to the United States, became a Baptist, taught at a German Baptist seminary. And Walter was raised in a very Evangelical atmosphere, went to seminary and, you know, it was a time when people were beginning to talk about historical critical method. People were beginning to talk about, well, what is the Gospel saying to the situation in the world?

Rauschenbusch’s first pastorate was in Hell’s Kitchen in New York City, which was, at that time, very aptly named. It was a really rough part of the world. He dates his real conversion to that experience. His first book was dedicated to the people of that pastorate, who opened his eyes for a second time because, you know, what he said about that time, he said, “I just kept burying too many babies. The little boxes, they broke my heart.”

And so he went down there to kind of, you know, transform their spirits and evangelize in a traditional way. And then he became determined because he said, “Well, what does the Gospel say about the lives of these people that are being crushed by poverty? I have to — I have to — as a pastor, I have to deal with this. I have to deal with the body of these lives.” He went back to the Bible and he has this great parable: A man was walking through the woods and all around him were the warbling of songbirds and yet he didn’t hear any of it because he was a botanist. And I think this is a great metaphor for how we approach the Bible. You know, we see there what we are expecting to see and then, when he went back with these eyes opened by, you know, the suffering of his congregation, he saw all these calls for social renewal and the idea that the Gospel also dealt with the person and with the lives on this earth, not just afterlife, but this life.

MS. TIPPETT: Now he took the Old Testament prophets as his guide and as his models. I love something that he wrote about them, just the way he wrote that. Figures like Amos and Jose and Isaiah and Jeremiah, “They lived in the open air of national life. Every heartbeat of their nation was registered in the pulse throb of the prophets.”

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Isn’t that great (laughter)?

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, it is.

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Yeah, and he thought that Jesus was the heir of that tradition, that Jesus was the heir and the culmination of the prophetic tradition and that Jesus had kind of brought that into fruition and, to understand Jesus, we had to look at the prophets.

MS. TIPPETT: And, you know, I could imagine somebody listening to this and saying, “Well, we’ve had Christians enter public life and what that has meant is entering political life and it’s associated with a number of issues.” I think it’s important, though, to really paint this canvas here because, in fact, Walter Rauschenbusch in many ways was quite a different kind of character and the Social Gospel was different. So let’s just flush that out. I mean, he had this insistence that it’s wrong to think of religious morality as the only thing God cares about. He said, “The social problems are moral problems on a larger scale.”

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: I think Rauschenbusch was in some ways a skeptic of religion, just as he was a pastor and, you know, a national figure on the religious scene. He didn’t de facto take the authority of religious figures. He said they always had to be set up against a test of how they would bring people together. Will they make us a more cohesive, more loving, more positive society? He also said that about Christians. You know, people can be converted and they’d be worse than they were before. Jesus said that about the Pharisees making converts and making them twice as fit for hell.

So it wasn’t just a fact of being more religious. It wasn’t a fact of being more religious like a certain kind of religion, Baptist or anything like that. It was really about how are you converted to this wider project of making a more beautiful world where actually heaven is created on earth and we can identify that by people living together peacefully and with equanimity and with more equality.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being — conversation about meaning, religion, ethics, and ideas. Today: “Occupying the Gospel” — with Huffington Post Religion editor Paul Raushenbush. His great-grandfather, Walter Rauschenbusch, went on sabbatical to Germany in 1907 just as his book Christianity and the Social Crisis was published. He came home a year later to find himself a celebrity. The dedication page of his book was a shortened section from the Lord’s Prayer: “Thy Kingdom Come! Thy Will Be Done on Earth!” Rauschenbusch’s de-emphasis on the afterlife and his insistence on the social responsibility of Christians in this life was criticized by some as leftist, even Marxist. But he had a strong friendship with his contemporary the capitalist John D. Rockefeller. In the 1960s, Martin Luther King Jr. cited Rauschenbusch as a deeply formative influence. And Walter Rauschenbusch is read and studied in seminaries — all kinds of seminaries — still today. He considered himself Evangelical, and he saw Dwight Moody — now revered as a founding father of modern Evangelicalism — as his forebear.

MS. TIPPETT: I know you’ve been inside this history, but there was also a rift that developed in that time, right? I mean, there was some parting of the ways among — between different kinds of Protestants and, in fact, a retreat from public life, which, in fact, was — in some ways those were the forebears of today’s Evangelicals who re-entered public life in the last few decades. Can you say a little bit about how that worked and what the dynamics and issues there were?

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Well, it’s interesting. When Rauschenbusch started, he hadn’t thought about the personal element of the faith — might also hold that, you know, kind of in concert with one another. Then, unfortunately, a split developed and, you know, for instance, the Social Gospel was never Rauschenbusch’s term. He didn’t like that term.

MS. TIPPETT: Oh, I didn’t know that.

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: He later used it in his last book, but he always resisted it. He said, “It’s just the Gospel. There is no social gospel or private gospel. It’s just the Gospel.” But then you had these divisions and people felt like it was just, you know, that there was no transcendent value to it, that it was just Marxism. And so people forget that Rauschenbusch actually worked with Moody, a very kind of traditional …

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Dwight Moody, yeah.

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Yeah. He translated some of his works into German. I mean, there was a cohesion there at the beginning that Rauschenbusch, it broke his heart. You know, his father, a lot of his colleagues at the seminary, there was a really big effort for him to keep people together, but afterwards, there was a strong split. What’s so interesting for me today is many of the descendants of those people who split off from the Social Gospel into fundamentalism or Evangelicals are now actually some of the most interested people in what the social elements of the Gospel have to say.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: These young — mostly young Evangelicals who are all of a sudden saying, “Wait a second. What does this have to do with the poverty I see around me?” And they become very active. So what I’m really actually thrilled about right now is this kind of, in a sense, reuniting of the social and the private religious fervor and, in some ways, working together to really see some of the common issues that we all want to face, such as hunger. I mean, a very basic one, poverty. I remember when I first released Christianity and the Social Crisis, the 100th anniversary edition, I contacted Brian McLaren and I said, “Hey, I’m not sure if you ever heard of Rauschenbusch, but I released this …

MS. TIPPETT: Part of the emerging church movement.

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Right. Right. He wrote me back this amazing email and said, “I’ve heard of Rauschenbusch and I heard all these sermons growing up about how awful he was and how evil the Social Gospel was. Then I finally read it and I realized, ‘Oh, my God, this is what I’ve been waiting for my whole life.'” So he had come this half circle towards, you know, wholeness and I myself had actually become a little more invested in this spiritual element of the Gospel because of the trajectory my life took.

MS. TIPPETT: Say some more about that trajectory for you.

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: (Laughter) So you know, I went to college and I majored in religion, but I became much more interested in rock ‘n’ roll and the rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle, and part of my history is just, you know, getting clean and going to a rough halfway house in south Boston and having this old craggy, Irish Catholic drunk woman — ex-drunk, I mean, she was a sober drunk. She, you know, would put my shoes under my bed and I would say, “Marilyn, why are you putting my shoes under my bed?” She says, “I want you on your knees praying.” The whole thing was this kind of transformation. That’s when I started to pray again, and that’s actually where I heard The Lord’s Prayer again because you pray that in AA.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. “Thy kingdom come.”

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: “Thy kingdom come,” and so it was like this it became such a part of my life. Then to kind of go back later to go into seminary and see like what part The Lord’s Prayer played in Rauschenbusch’s life and his thinking and just realizing this is all a piece, this is all a part of the whole. It was so beautiful. So for me, you know, it’s been an ongoing process of, you know, beautiful discovery.

MS. TIPPETT: And so you — you went to Princeton, is this right, in 2003? Is that when you started working?

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Uh, yeah, I mean, I, you know, I had a series of different kinds of jobs. I worked at the Riverside Church and I’d worked as a chaplain in a drug rehab center in Brazil and all sorts of street kids in Seattle. But I got called to service, Associate Dean of Religious Life in the chapel at Princeton in 2003, which was an incredible honor and privilege.

MS. TIPPETT: And you know, I can’t imagine that this path that you’d walked, which was growing up with religion as an influence, leaving it behind, coming back with some curiosity, I think that that’s a pretty common trajectory in this culture. I don’t know. I’m just curious about what you discovered there, how you also understood that in terms of your own journey and also this legacy of Rauschenbusch, which I almost feel like you kind of embody as much as know about, how you then brought this life and legacy of yours then together with this life of students in our age.

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: The great thing about religion at a place like Princeton is that the students really care about knowledge. They’re very curious. They want to know. They’re not willing to, you know, kind of X anything out very quickly. One of the kind of daunting things was I never had to kind of say, “Hey, everybody, pay attention.” I mean, they were there, you know, I mean, they were interested and they were looking for authenticity.

I think that what young people are looking for more than anything is authenticity. They want to know. They’re looking for meaning. They’re looking for truth. They’re really trying to work these things out in a lot of different ways and I found the interest in religion coming from all different religious traditions. I mean, what’s interesting is how much interest there is in religion on university campuses these days.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. I don’t know that that story’s really been told, but people …

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: It’s amazing. I mean, there is incredible attendance in all different religious traditions. There’s great interest. I mean, I had a group of about 25 students who applied to be on this interfaith council and, you know, often we could only accept about 30 percent of the people who applied to be part of this interfaith council, which means that — and all of them were qualified. It just means that there was a hunger for these conversations, for honest, truthful, authentic conversations. It’s a wonderful thing.

I always say that one of the reasons I’m so hopeful about the world is because I got to work with students for a long time, also in such a heightened intellectual atmosphere which really approves of curiosity, approves of exploration. I think we need more spaces like that in our churches and synagogues and mosques where we really approve of that kind of curiosity, where that’s part of what we think of as a religious message. Rather than certainty, actually, curiosity is what defines a religious person.

MS. TIPPETT: This conversation with Paul Raushenbush sent us looking for his great-grandfather’s prayers. They are poetic and filled with imagery from the natural world. The Thanksgiving prayer mentioned earlier draws to a close with these lines: “Grant us a heart wide open to all this beauty; and save our souls from being so blind that we pass unseeing when even the common thornbush is aflame with your glory.” Find that prayer and another one we loved at onbeing.org.

Though I’d read Walter Rauschenbusch when I studied theology, I hadn’t realized until now that the phrase “What Would Jesus Do?” came out of his Social Gospel movement. In our time, the acronym W.W.J.D. is pasted on car bumpers and threaded into bracelets and associated with Evangelical Christianity and an emphasis on personal morality. But in its origins a century ago, it was primarily an expression of the conviction that social justice issues are moral issues writ large. So we called up a theologian, John D. Caputo, to hear the fascinating and little-known story behind this phrase — it’s also a story of the nature of the split between what we now know as Evangelical Christianity and mainline Protestantism. It’s a split, as Paul Raushenbush points out, that new generations are reframing. Find more on our blog at onbeing.org.

Coming up, what happens when a theologian from an historic Christian lineage takes up religion on today’s online frontier.

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: It’s very funny because I’m always saying, “This is really interesting but could you make it more religion-y?” I think people, you know, sometimes when people approach me initially they think they have to kind of erase out the specificity in order to make it OK for everyone. I’m like, “No, no, no, no I really want you to reference the richness of your tradition so that I can learn.”

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett. This program comes to you from APM, American Public Media.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett. Today, On Being: “Occupying the Gospel.” My guest, Paul Brandeis Raushenbush, is the great-grandson of Walter Rauschenbusch. He was a galvanizing social activist Christian leader of the early 20th century. Martin Luther King Jr. said he learned from Rauschenbusch, quote, that “any religion that professes to be concerned about the souls of men and is not concerned about the … social conditions that cripple them is a spiritually moribund religion awaiting burial.” Paul Raushenbush is a rock ‘n’ roll producer turned college chaplain and now editor of the Huffington Post Religion section. He helped launch it in February 2010.

MS. TIPPETT: So you from those earliest days committed yourself openly to convening a discussion that was going to happen between the strident polls of strident religious voices on one end and strident voices, as you named, on the atheist side who denigrate religious people and their traditions. But you’re doing this on Huffington Post, which itself has a very, let’s say, a liberal reputation and can take a very liberal strident tone. How do you walk that line? Is that a challenge?

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: You know, we don’t really — you know, I — honestly, it’s not about left-right liberal-conservative. In some ways, it’s about trying to figure out like how do you live life well? I mean, we do have people who come in with really hard-core political views and then they say, “And Jesus said love your neighbor.” I’m always like that’s kind of lazy. You know, I mean, let’s really actually start with what Jesus said and then whatever evolves from that. But I really sometimes say, “You know, it’s not OK.” What I’m not looking for is just like political view plus Jesus.

It has to be like really more and more I’m getting a much broader kind of audience and much broader kind of writing, you know, bloggers who are really interested in being a part on the same page, not necessarily agreeing with, but on the same page as people who think differently. And so we’re really trying to get beyond this kind of left-right. You know, I’m actually — the one thing I really don’t like on the page is like people who are just so stridently anti-religion that they’re just like all religious people are idiots. I mean …

MS. TIPPETT: That’s a lot of the comments there?

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Yeah, we have a lot of comments like that. You know, I kind of feel like the women’s section of this site wouldn’t have like blatant misogynists. We don’t have to have people who just hate religion and think, you know, simplistic ideas that religion is the source of all evil. I mean, it’s just …

MS. TIPPETT: I mean, what’s that about? Where do you see that coming from in our culture? Because it is a kind of stridency that resides more on the liberal, or whatever these labels mean, in American secular liberal culture, though, isn’t it? I don’t know.

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Yeah. I mean, that may be the case now. It certainly wasn’t the case with, you know, Martin Luther King Jr. or other people. I think it’s a fairly recent phenomenon, but the idea of liberal versus religious is just a crazy dichotomy and it doesn’t take into account any of the actual history of America. I want to say one other thing about that. There are atheists who are interested in interfaith conversations and there are secularists who really want to be part of a conversation about meaning, and I think that’s important. I do. I always want to know, OK, so what are the seculars bringing to the table? Like one of my cousins …

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm, in terms of positive content?

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Well, in terms of tradition. I mean, my cousin dink Rorty, who wrote the afterword to Christianity and the Social Crisis, was a very famous secular humanist who was, you know, a philosopher and a pragmatist and one of the most well-known philosophers of the 20th century. He was an amazing man. I loved to hear him talk. I loved to hear his ideas. I thought it was so important what he had to say. So what I’m looking for, for people who are not religious or who come from a secular humanist tradition, is bring it. Where do you find your roots? You know, figure out what you believe and why you believe it.

MS. TIPPETT: And do you think that’s a challenge for modern people? I mean, I feel like there’s a few generations here, especially when you and I were growing up, where it was actually not an intelligent, educated thing to have deep convictions and present them. Because, in fact, it might work against tolerance and pluralism.

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Right. I think that the idea of — I mean, in some ways, it ties into this idea of, OK, what do I want to say about that? In our personal conversations, people never talked about religion. Only later did I figure out that a couple of my good friends in high school were Jewish. We just never talked about it.

MS. TIPPETT: Right, and didn’t know how to talk about it, right? I mean, didn’t actually have a robust, intelligent vocabulary for talking about it outside the confines of our own …

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Well, we were told not to talk about it.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: You know, religion is something you don’t talk about. So we privatized it in such a way that we didn’t have the language to talk about it. I think that that was a polite way to interact it, but it’s such an amazing thing. The moment you ask someone like, “What do you really believe? What is your tradition?” It opens everything up.

MS. TIPPETT: So I think you’re getting at something that actually is quite striking when you go to the Huffington Post Religion site and there’s a lot going on there. But there’s a lot of stuff that’s very straightforward that I hadn’t thought about this way. But it is along the lines of developing a vocabulary and a basic knowledge, right? What is Shariah and why does it matter? What does the Bible actually say about gay marriage? You’ve told me that some of the things — some of the pieces that get passed around the most are about Scripture.

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: (Laughter) Tell me about that. I mean, what gets passed around?

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Isn’t that amazing?

MS. TIPPETT: Well, tell — yeah.

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Yeah, it’s — it’s, you know, we started doing these pieces where it was, you know, what does the Bible say about women? What is the Bible? You know, one of the biggest pieces to date is this piece that said the five things you should know about the Bible. You know, it’s very important for me to have intelligent voices about what Scripture is, to have a piece about Shariah law. We’re talking about Shariah all the time as if we know what it is, so we’d better know what it is. So to get the foremost scholar on Shariah to write a piece about it so that we can actually have an intelligent conversation about it, I mean, you have to know. One of the traditions that I love from the Brandeis household was they would be having a conversation and, if they didn’t know a fact, they would actually stop and look it up before they continued, whereas my tendency …

MS. TIPPETT: And they didn’t even have iPads, right?

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: No, they didn’t have an iPad. They would actually go to the encyclopedia. You know, it’s really very funny. Our tendency is just to go, OK, well, whatever. Let’s keep going. I mean, the opportunity here with the Internet is that, if you know how to sift through a lot of the garbage that’s on the Internet, you can find real knowledge and that’s part of what my job, I feel. This ministry, the reason I’m doing this is it feels like a calling, is to push as much positive, as much productive, as much intelligent information out into the Web as possible.

MS. TIPPETT: What else has surprised you, either that’s come in or that people have read and commented on and passed around in that online world?

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Well, I think what’s been interesting for me, we do have all these comments that come in and very kind of vicious. It’s like a very sort of mean …

MS. TIPPETT: Kind of a big contrast between the high tone of the blog pieces and the low tone of the commentary.

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: The bite that happens on the comments. But what was interesting for me personally to experience was when I had the tragedy and my nephew died and it was just a heartrending thing and I published the eulogy I gave in honor of Sam.

MS. TIPPETT: He was a young man, right, 20?

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Yeah, he was 20. I mean, it was just awful. I made myself vulnerable, it’s very clear, and the comments were so amazing because they were talking about people who they’d lost. Then there was this one person who wrote, like, “Well, I’m sorry about your nephew, but you know God is a fairy tale and you shouldn’t. …” and the rest of the commenters all kind of ganged up on him. They said, “What are you doing?”

So there is a soul out there. I think what’s been interesting for other pieces like that, when people are vulnerable, people will pass it along and say, “Did you see this?” because we’re all hurting, left, right, it doesn’t matter. People hurt, people go through pain, people are looking for some sense that they’re not alone. It’s not just kind of, you know, knowledge or kind of ideas. It’s also about the truth of life, the truth of what people are going through. And if you can convey that, I think it’s respected on the Web.

MS. TIPPETT: It’s interesting. I mean, you hear a lot about the Web as this free-for-all. I mean, that’s it too much information, I mean, it’s open to an extreme. But I don’t know that I’ve heard people talking about vulnerability online. And I wonder if you think maybe that — because say one thing I really treasure in religious traditions that I think is in contrast to our culture is that they actually honor human vulnerability and, you know, meet us there and ask us to make sense there. Do you think that it’s because of the subject matter of Huffington Post Religion that maybe something special in terms of people showing vulnerability and responding to it online becomes possible?

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: That’s what I’m hoping for. I mean, I think of prayer services where people say, you know what, I’ve lost my job and I just need prayer. When I worked at Riverside, we would have prayer services like that. So what I would like, you know, is for people to have that sense of meeting someone there, even if they’re not of the same religion, even if they don’t agree on many social issues. I want people to actually feel like there’s a basic humanity to the site.

We had an ongoing series. Every day, this imam wrote about Ramadan and about what he was going through and about the thoughts and the difficulties and all this kind of stuff, and it was very personal and very beautiful. I was following it and I was just like, wow, this is such an insight into someone else’s heart that is from a completely different religious tradition than mine, and it felt like an honor to be able to read it.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being — conversation about meaning, religion, ethics, and ideas. Today: “Occupying the Gospel,” with Huffington Post Religion editor Paul Raushenbush.

MS. TIPPETT: What do you feel, what have you learned, what new sense or ideas do you have about American religious life, not politics, but the religious life in this country? How has this experience of Huffington Post Religion, of working on this online, in fact, creating a new space for this, what do you know now or what feels more important to you that you didn’t see before, didn’t grasp before?

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: I think how eager everyone is to be on the same page.

MS. TIPPETT: To be on the same page.

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Not thinking the same thing, but being together on the same page.

MS. TIPPETT: I see (laughter). On the same page, yeah.

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Yeah. By page, I mean the Huffington Post Religion, yeah. You know what I’m saying?

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: So, you know, I kind of intentionally made that a little confusing because I think we see this around questions of, you know, what’s the role of pluralism in American society? How are we going to understand our Muslim neighbors? How are we going to deal with the true humanity of gay people? You know, all of these things that are in the mix. I see how much, you know, the Sikhs, the Hindus, the Buddhists say, “Everybody is kind of looking to have a voice, to be a part of a general conversation.” I’m hoping that that actually reflects what’s going on in America. But I think that, in some ways, there is a question there. Are there some people who just, you know, kind of refuse to be in the same space as people who they view as other?

MS. TIPPETT: But, you know, I think something that’s worth teasing out is, you know, when you say on the same page, I think it can — not this new online way, but the old way — it can suggest agreement and it can suggest at least kind of a surface agreement that may not be very rich or interesting. But one of the emphases for you, I mean, I think personally as well as an editor, is that you really — and maybe this the Walter Rauschenbusch gene in you also — that you really want people to be grounded in their texts and traditions. And so, I mean, it’s interesting that you can create this diverse space, but there’s so much going on that is about that kind of grounding in one’s own beliefs as well as, as you said, the curiosity about others and that there’s no contradiction there.

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: No, no. In fact, I’m always — it’s very funny because I’m always saying, “This is really interesting, but could you make it more religion-y?”

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Uh, you know, like could you really, like, I think people, you know, sometimes when people approach me initially, they think they have to kind of erase out the specificity in order to make it kind of OK for everyone, I’m like, “No, no, no. It’ll be much more interesting for everyone if you go deep into what your specific tradition is.” That’ll be a much more interesting read for me. I want to know actually what the Hindu roots of your understanding of life or loss. I really want you to reference the richness of your tradition so that I can learn.

So I’m always kind of going, you know, it’s very — it’s very funny. People are surprised, but that’s my standard line: “This is good, but it could be a little more religion-y” (laughter). And by religion-y, I just mean go deep into your tradition. Don’t be shy about it. And I think one of the sad things, I guess, about my own kind of upbringing — and this is not my parents’ fault, believe me. I’m the one who skipped confirmation. But how, um …

MS. TIPPETT: But maybe generationally.

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: It may be generation, but I do, you know, I think that the idea of going deep into Scripture, going deep into tradition and finding its richness is something that I want to make sure that the main-line church, which is my tradition, make sure that they appreciate how important it is to know the Bible, to get deep into the Bible, to know the great thinkers, the great sages, the great wisdom teachers of our own tradition. Then you can go out and be conversant when you talk to a Jewish person who has done the same thing in their tradition. It’ll make the conversation way more interesting. It’s exciting and, again, it goes back to this curiosity, curiosity about the other, but curiosity about where you come from, learning from your grandparents. What’s the intellectual tradition you come from? What’s the spiritual tradition you come from?

MS. TIPPETT: And just to speak to that eagerness too, I just remember looking at, say, for example, a video piece you did where you just went out on the street and you asked people about prayer, right? About their prayer life? What was the question you asked?

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Oh, I just said, “What do you think about prayer?” [laughter]

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, and how do you pray?

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: That was the follow-up. You know, basically, I just was like, “Hey, what do you think about prayer?”

MS. TIPPETT: What was so interesting is how people engaged that question, right?

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: So differently, yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: So there is the fact that we haven’t known how to talk about this and we haven’t talked about it, but like when you just walked up to people and asked that simple question, they were absolutely ready to go there with you and shared much more than I expected in every case.

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Oh, yeah, and there was so much more that, of course, we couldn’t include like always. But it was just — it was amazing and you just kind of sensed that people wanted to talk for a long time about it, and that’s what everybody’s walking around with, a kind of hunger to have this conversation about what’s dear to them. And even if it’s not dear to them, you know, like “I don’t pray.” Like one person was just like she wanted to talk. She was like, “I don’t pray. I’m agnostic, but I think it’s this.” You know, it was very beautiful. It was like an engagement with an idea and people have a lot to say. We have so much to learn from one another.

[Sound bite of people on the street talking about prayer]

MS. TIPPETT: I wanted to quote you some lines of your great-grandfather Walter Rauschenbusch, whom we started out talking about. “Religion is a tremendous generator of self-sacrificing action.” “If the hydraulic force of religion could be turned toward conduct, there is nothing which it cannot accomplish.” I really like that. I’ve thought and I’ve said openly, so Christian voices in particular re-entered public life and political life in a big way in this country a few decades ago, but it’s not associated with conduct. It’s associated with issues. But I wondered, I mean, when you hear those lines about this hydraulic force of religion, if it could be turned toward conduct, there’s nothing which it could not accomplish. Do you believe that? And what does that suggest to you? What would you like to see that look like?

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: I think it’s such an interesting quote. And I guess, for me, part of the history is following the trajectory from Rauschenbusch to Niebuhr to King, as well as seeing, you know, the divergence of people who left and then came back. Part of what I see today is, you know, the power of religion is not just about like the hydraulic push, but it’s also in some ways to hold back. How does religion force me not to seek out more things, more power, more money?

I think, in some ways, what he was talking about there is that religion has a power to make us put other things in front of our own drive towards accumulation, drive towards me, me, me. And so the power of religion in some ways is to choose not to do it, whether that’s, “I will not pick up a gun.” “I will not destroy the environment.” I will not bully.” You know what I mean?

The power of religion is to actually offer a transcendent vision of what’s more than just me, what’s more than just my own needs and my own goals and to say actually I have to look at this with a bigger vision. For Rauschenbusch and for me, it’s still what does the Kingdom of Heaven look like? What is a wider vision that will allow me to live my life in accordance with a higher ethic? And religion can do that. It can help people. You know, part of the effort here is to figure out how navigate the religious voice so that it really does that in a responsible way and a way that is beneficial to everyone.

MS. TIPPETT: I know that, in that letter in February 2010 where you introduced Huffington Post Religion, you also — and since then you’ve talked about wanting it to be a place where religious and nonreligious people can in fact interact and that nonreligious are ethical and moral beings as well. Has that happened and do you see that as, you know, something that’s also evolving at this point as we move through the 21st century? That some of these important ethical discussions are also happening across that divide, not different religious people, but religious and nonreligious?

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Absolutely. I see the idea that religious people have some sort of monopoly on morality is absurd. But, again, you know, the question is, OK, so where does your morality come from? Again, I bring in my cousin, Richard Rorty, who had such a clear sense of where he was coming from and what he was drawing upon.

MS. TIPPETT: He was a secular atheist.

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: He was a secular humanist and, frankly, a boogeyman for a lot of the Religious Right. But, you know, he cared so deeply about people and the pragmatist tradition and how we are going to get better and how we’re going to keep moving forward, and that was someone who I just wanted to work side by side. I wish I could do half of what he accomplished.

And so there’s the opportunity here to really learn from one another and to really grow. I have something to learn from the pragmatist philosophical tradition. You know, a great friend of mine and mentor is Cornel West, who also came out of that tradition, was a student of dink Rorty’s. So he’s someone who is a professing Christian and also a pragmatist. We have much to learn from one another.

MS. TIPPETT: So how has this experience so far, this interactive online religious life that you live and foster, you know, how is it — I think this is a very hard question to answer. I hate it when people ask me this, but I’m going to do it to you anyway [laughter].

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: Great.

MS. TIPPETT: How does it flow into your sense of faith and your — you know, how has it changed your sense of the places religion faith in our common life?

MR. RAUSHENBUSH: You know, I’m not kind of a journalist. That’s not my primary sense of who I am. My primary sense of who I am is as a minister. So but how does it affect me personally is kind of a harder question. It’s hard because you realize how much is out there and, in some ways, like all day long, I’m reading opinions about what people think about the world and about the ultimate questions.

What I have to be on guard against, and I think we all do, is kind of saying, OK, yeah, that’s just that. You know, kind of, in some ways, making it too simple, when these things are so complex. So what I have to remember is that all of it represents lives, and I have to make sure that I’m taking care of myself and I’m being a part of some sort of spiritual community or tradition so that it doesn’t just become sort of process the information. It becomes actually like remembering that each one of these people is a child of God, you know, honoring them with what they have to say. But it’s tough because it’s a very fast-paced place. You know, I have to be very careful about how I approach it and keep my soul steady [laughter].

MS. TIPPETT: Paul Brandeis Raushenbush is the Senior Religion Editor for the Huffington Post. He edited Christianity and the Social Crisis in the 21st Century — a hundredth anniversary edition of his great-grandfather Walter Rauschenbusch’s classic text of the Social Gospel movement. The final chapter of that book includes these lines:

“The Kingdom is always but coming. It is true that any effort at social regeneration is dogged by perpetual relapse and doomed forever to fall short of its aim. But the same is true of our personal efforts to live a Christian life; it is true also of every local church, and of the history of the Church at large. Whatever argument would demand the postponement of social regeneration to a future era will equally demand the postponement of personal holiness to a future life.”

We talked about Huffington Post Religion this hour, but it’s worth pointing out that there’s a growing sphere of religion news and discussion online, with a vast array of viewpoints and approaches. Here are some of our favorites: CNN’s Belief Blog, Christianity Today, USA Today‘s Faith & Reason, Religion Dispatches, and The Revealer. I’ve contributed to a few of these as well as the Huffington Post. Find this list at onbeing.org, where you can also listen again, download this program, and much more. “Like” us at facebook.com/onbeing. And follow us on Twitter; our handle: at Beingtweets.

This program is produced by Chris Heagle, Nancy Rosenbaum, and Susan Leem. Anne Breckbill is our Web developer.

Special thanks this week to Christopher Evans. He is the author of The Kingdom is Always But Coming: A Life of Walter Rauschenbusch.

Trent Gilliss is our senior editor. Kate Moos is executive producer. And I’m Krista Tippett.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: Next time, for Thanksgiving: “The Poetry of Creatures.” We explore a new reading of the Bible’s sense of the relationship between human beings and the natural world. We speak with biblical scholar Ellen Davis, and Wendell Berry reads some of his poems. Please join us.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.