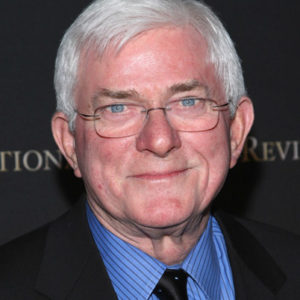

Phil Donahue

Transformation, On-Screen and Off

Talk show pioneer Phil Donahue opens up on his remarkable perspective on the last half century of America and who we are now. He shares his personal transformations on race, gender roles, and parenting in the dramatic era he captured on television.

Image by Mark Mainz/Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Phil Donahue was the host of the daily talk show Donahue from 1967 to 1996. He's also an author and the producer/director of the documentary film, Body of War.

Transcript

December 12, 2013

MR. PHIL DONAHUE: All right, Krista. Me and you, kid. Where’d you go to school?

MS. KRISTA TIPPETT: Well, I grew up in a small town in Oklahoma and then I went to Brown which was a very strange move.

MR. DONAHUE: My wife wrote a book titled “The Right Words at the Right Time”. What did somebody say to you at one point in your life that changed your life? You could write your own or you could have someone write for you and you had, of course, final cut. Or you could be interviewed. And I did two. I did Muhammad Ali and I did Ted Turner. And Turner’s, as I recall, was a professor at Brown. He had a professor who taught the students to think outside the box.

MS. TIPPETT: Did anyone ever interview you and ask you that question?

MR. DONAHUE: I wrote one.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. About yourself?

MR. DONAHUE: Yeah, an incident, an incident.

MS. TIPPETT: About your own moment? What was yours?

MR. DONAHUE: Are we on the air here?

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah [laughs].

[Music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: Phil Donahue’s pioneering daytime talk show launched in 1967. He had a front row seat on the world so many of us are now reliving through Mad Men. I watched the Phil Donahue show when I was growing up. But it wasn’t until I looked back at his work that I realized how substantive a lens it was on an entire era of social, personal and political transformation. His very first guest was the controversial face of public atheism, Madalyn Murray O’Hair. He engaged the emerging world of militant Black leaders. He presented a “gay man” to his audience as a human being. Above all, Phil Donahue’s choice of guests and topics respected the intelligence of the housewives of his audience, who themselves were in a coming upheaval.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

I met Phil Donahue at the 2013 Nantucket Project on Nantucket Island, Massachusetts. At 77, he still has the full handsome head of gray hair for which he was always recognizable. He’s still married to the actress Marlo Thomas, who he memorably met in public on his own set. Phil Donahue grew up in a big Catholic family in Cleveland, studied at Notre Dame, and got into radio before he wandered into television. And that was the backdrop of the answer he gave to that question about a turning point of insight.

MR. DONAHUE: I was covering a mine disaster in Logan, West Virginia for a local television station at which place I was employed in Dayton, Ohio. and I’m like 23 years old. I must have looked 19 or 12 and I don’t know if you can appreciate what it was like for me to be covering for CBS radio. I think there were like 28 miners trapped. And, oh, yeah, they wanted this. So we used to have to — it was snowing and we had to keep the camera warm so that the oil didn’t freeze. Otherwise, it would screech. And we were by the smudge pot which is what the miners gathered around when they would come out of the mine. They would work in shifts trying to reach their brothers who were trapped.

And the snow is falling and the miners with, you know, the soot on their faces would gather around the smudge pot and pray for the survival of their friends who were trapped.

And I remember the song, the hymn, they sang was — I can only remember part of it — “What a friend we have in Jesus, everything to God in prayer.” And the sparks flew in the air, the snow was coming down.

It was the most beautiful, humble tableau of faith and religion I’d ever seen and the preacher would, after the singing, would say, “Dear God, we are gathered here on this mountain and we ask your blessing on these miners and their families. Please help us rescue them, dear Jesus, in your name we pray. Amen.” And I realized that we hadn’t filmed this.

And I went up to the preacher and I said, “Reverend, I’m Phil Donahue from CBS News and we didn’t have a chance to film you and we very much would love to get this on film so that we can send it to CBS News.” And he said, “Well, sir, I’ve already prayed to my God and it just wouldn’t be right to do this a second time.” And now I’m begging.

MS. TIPPETT: Right, right.

MR. DONAHUE: “Reverend, your prayer will be seen in taverns.” At that time, TV was mostly in bars. “And the American people will see the power of your faith in your prayer.” “No, sir, I have already prayed. I’m sorry. This would not be true to God’s word and His truth and my truth and the truth of these families.”

Well, I went down to — the telephone company had put up some payphones for the media and I got in that payphone and I closed the door, I dropped a quarter in, called collect to CBS News in New York. I mean, I’m holding this phone. I could see my knuckles were white and into the phone, I said, “The son of a [bleep] won’t pray.”

And I think it must have been maybe a week or two — I’m a slow learner really, suddenly after we had gone home and I think they lost most of the miners. I don’t think anybody was saved. And, of course, I couldn’t get this out of my mind and I realized that I had been witness to the most beautiful demonstration of moral courage I had ever seen in my life.

And I put the story in Marlo’s book and, you know, it called to my attention the Pharisees and the Publicans — I forget which was which. The Pharisees, I think, go up to the altar and they say I am here, Lord, I love you, Lord, and I am here.

MS. TIPPETT: Right, right. They put their faith on display.

MR. DONAHUE: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes.

MR. DONAHUE: And the pomp and grandeur of some religious personalities in our nation who would have no trouble throwing holy water again, if one of the stations missed it, at a plane accident or whatever, you know, to get on TV. And this humble cleric — I’m sure he was Protestant — would not pray again. He had already prayed.

MS. TIPPETT: And did that imprint you as a — I mean, clearly it imprinted you on a human level, but did it influence the trajectory of your work in media?

MR. DONAHUE: Well, this was at a time when I was really becoming a little more questioning.

MS. TIPPETT: Because you had had a very serious Catholic upbringing.

MR. DONAHUE: Very serious.

MS. TIPPETT: Yep.

MR. DONAHUE: My mother would say there are two kinds of Catholics. There’s a Catholic and there’s a good Catholic. I never quite understood what was the difference, but my mother apparently knew. I was a good Catholic. Of course, I never missed Mass on Sunday. Our family went every Sunday. And this would be — I was early 20s, so this would be not long after I graduated from Notre Dame.

I entered Notre Dame, you know, thinking that I had the answers to all the questions and I graduated from Notre Dame realizing that not only didn’t I have the answers to all the questions, but the questions were now more exciting for me. It was like I was free to question things that I had never — we did have a very liberal priest at the time at Notre Dame and the subject matter just thrilled me. We could read books on the Index. The lndex was a list of books that Catholics were prohibited from reading.

MS. TIPPETT: Oh, wow.

MR. DONAHUE: And it was just a thrill, like a vicarious thrill. I remember reading Immanuel Kant, “Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysic” and I used to tell that to girls that I was dating, you know. Yeah, I’m reading “Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysic”, you know.

MS. TIPPETT: Was that attractive? Did it… [laughs]?

MR. DONAHUE: As I recall, it didn’t work that much, you know. I still don’t think any of them kissed me goodnight, which was about as warm as you got in the 50s. I graduated from college in 1957.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. DONAHUE: You know, I was a virgin when I got married. I obeyed all the rules and then suddenly, you know, I began to see Catholics voting for Nixon in the 60s, supporting the Vietnam War. And my wheels started to turn, you know.

[Music: “Carving” by Michael Brook]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today with daytime talk show pioneer Phil Donahue.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, the show you did in the era, in those years in which you created that show, I mean, one thing that I — so I watched your show, right? I mean, I was born in 1960.

MR. DONAHUE: And you turned out anyway, huh? By the way, my show was born in 1967.

MS. TIPPETT: ’67, yes. So, I mean, in my growing up years, right? So one thing as I knew I was going to interview you, I understood better what partly what was so unusual that you innovated, which was pure talk without entertainment, right? And it actually struck me as I was looking back at some of it and also looking at what you’ve been doing more recently.

And — you know, what you were doing, what you were drawing out of people and for this American audience was this exploration of the human condition as it relates to society and politics. And those were wild years for the human condition. They were wild years for society and politics. Why was Madalyn Murray O’Hair your first guest?

MR. DONAHUE: Because I knew she was compelling. We had a very boring show visually, two talking heads.

MS. TIPPETT: Which was unusual then, right?

MR. DONAHUE: Which was unusual then, right?

MS. TIPPETT: Which was unusual then, right?

MR. DONAHUE: Oh, we were competing with other shows. “Come on down” with spinning wheels and people screaming and Monty Hall was giving away $5,000 to a woman dressed like a chicken salad sandwich, “Let’s Make A Deal”. And here I come with two talking heads. The industry didn’t understand us at all. And we were in Dayton. Stars were not available to us. So I knew that the only way we could survive would be issues, something that would compel the viewer.

MS. TIPPETT: And did you know that at the outset? Did you understand that that’s what — you had to make the issues vivid?

MR. DONAHUE: Yes. Remember, I had come from a radio show where I could have the guest long distance so that pretty interesting guests didn’t have to — nobody’s gonna fly to Dayton, Ohio to be on a radio show. And I had interviewed Madalyn on the show and, religion, I just was fascinated with.

I am now and I was then, especially coming from Notre Dame and the, you know, the “Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysic”, because my own head was starting to change. And the devil, as it would be known then, was tempting Phil Donahue, of all people, 16 years of Catholic education and the devil was saying why are these religious figures so interested in publicity and wealth and why do the wealthiest people in the parish get entree to the pastor that the common people do not?

MS. TIPPETT: And it’s probably hard for people to even remember how controversial an atheist — a prominent atheist like Madalyn O’Hair was in the 1960s.

MR. DONAHUE: Absolutely. Right. It was the worst you could be. It was right there with gayness. Of course, we put a gay guy on…

MS. TIPPETT: I know.

MR. DONAHUE: In November of 1967.

MS. TIPPETT: ’67.

MR. DONAHUE: Yeah, before Stonewall, over a year before Stonewall.

MS. TIPPETT: But also, just that, like that, right? You put a man in the chair who was a gay man and that was this specimen of something.

MR. DONAHUE: I was like — I mean, I was scared to death, ’cause I felt they’re gonna think I’m gay and, you know, nobody was out in 1967.

MS. TIPPETT: Did you use the language of gay? Was that the language or was it homosexual or…

MR. DONAHUE: Isn’t that a good question? I don’t remember.

MS. TIPPETT: The language is so evolving so rapidly now.

MR. DONAHUE: I just can’t get over it. I got a call, an email, from a young man in Michigan or somewhere in Wisconsin, I forget. And he said, “Dear Mr. Donahue, I heard you say on Oprah that you put your first gay guest on in 1967. I think that is my uncle who has passed and do you have a tape?” I wrote him back and I said, “We didn’t know we were gonna be The Donahue Show in 1967.”

And I said, you know, “VCRs may have existed then and someone may have taped that somewhere, but I regret I know of no copy of that program. But I would like you to know that I think your uncle was as powerful a demonstration of moral courage as I’d ever seen and I also think the program rises to the level of historic because nobody else was acknowledging gayness.”

MS. TIPPETT: What was the reaction?

MR. DONAHUE: Well, pretty severe. We lost sponsors, mothers thought their children would catch it if they saw it. Why are we aggrandizing this man? To put him on television makes him look like he’s a hero or something. Just disgust. And thank God we had a general manager who didn’t drop his tools and run. He stuck with us and one of the reasons he did was that we had a tremendous rating. Everybody was watching The Donahue Show. And in my business, the coin of the realm is the size of the audience.

So, you know, that was my trump card. We were drawing a huge audience. This general manager, it wasn’t easy. It would have been much easier to cancel us. It would be much easier to run reruns of I Love Lucy. We were on the air at 10:30 in the morning. There was all kinds of product out there that could have — and a lot less trouble. You know, this was the first month we were on the air. We premiered on November 7, 1967 with Madalyn. There is no God, there’s no heaven, there’s no angels. When you die, you go in the ground and you biodegrade and you become part of the physical universe.

Well, my dear, you know, the whole town of Dayton fell down and the letters came pouring in. But I don’t want to overstate it. Dayton is a town that’s built on a — the river that runs through Dayton, the Miami River, is not navigable. It’s a town built on brains starting, of course, with the Wright Brothers. The viewers in Dayton accepted our show, by and large. Certainly, certainly we took our hits. People pushed back and I had salesmen from my station outside my office doors, you know, who weren’t interested in a speech about the First Amendment. They just lost Roger’s Pontiac, you know, and they had kids too and a mortgage. But somehow we survived all that.

MS. TIPPETT: And the other thing that you did that I think there was a lot of awareness about at the time — I mean, one of the things you were doing is you were broadcasting to a lot of women who stayed at home.

MR. DONAHUE: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: And most women of a certain class stayed at home at that time. And you were assuming that they had brains, right? You were presenting — you were putting a lot of subjects and complexity on at that time of the day.

MR. DONAHUE: It’s amazing to realize how sexist the world was and certainly my industry was. Women cared only about covered dishes, needlepoint, babies and maybe home decoration. And we came barging in with all these issues, including war and peace and protest.

MS. TIPPETT: But you were pretty traditional also, I think, in your first marriage. I mean, I did get your memoir that you wrote way back then out of the library. And you describe yourself also has have coming out of that world that in fact was shifting.

MR. DONAHUE: Absolutely. We rode the feminist movement, the gay rights movement, the antiwar movement. We put tie-dyed t-shirt kids on with long hair and this is in the late 60s who were protesting the war. We had a woman on whose daughter was a student at Antioch College and she was in the Green County jail having been arrested at a demonstration and fasting to end the war.

And the women in the audience were saying, well, what if she dies? And the mother would say, why aren’t you concerned about the 300 young men coming home from this horrible war in Southeast Asia in plastic zippered bags? Why don’t you care about that? And then another one would say, well, I do care about that, but this is your daughter.

I couldn’t get them to — and we had something that no one else on television had. But sexism reigned. It was a huge issue at the time and what we did was, you know — feminists would come into the show and they would say children get too much mother and not enough father, and they were talking about me.

MS. TIPPETT: And were you having that experience in real time?

MR. DONAHUE: Oh, sure.

MS. TIPPETT: In some way, it’s like you had this front row seat on the 1960s and 70s.

MR. DONAHUE: I did.

MS. TIPPETT: And you were able to like invite the whole cultural negotiation into the seat across from you.

MR. DONAHUE: I would wish this good fortune on anybody I love. It was a wonderful experience. I had every issue on a platform that had my name on it. And to this day, people come up to me in airports. “Thank you, Mr. Donahue. Because of your show, I got out of an abusive marriage.” “Thank you, Mr. Donahue. Because of your show, I came out to my parents.”

A woman told me the other day at 10:30 every morning, her mother would put on her lipstick and go into another room and close the door and watch The Donahue Show. So we became kind of appointment television and especially for seniors, you know, older women. And we did shows with feminists who would say out loud, “I don’t want to live the life of my mother.” And you’d have people calling in, “I’m not a feminist, but…” and then they’d proceed…

MS. TIPPETT: Now that’s what younger women say, again it’s come full circle [laughs] in a different way.

MR. DONAHUE: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: And then were you — you know, were you aware that this was changing you? Were your views of women changing?

MR. DONAHUE: I don’t know. It’s hard to say. Certainly somewhere along the way, I thought, you know, Dad gets up and has a leather suitcase and goes off in the car to the building downtown and Mom goes in the basement to do the laundry and what this was doing to children, girls especially. And then legislation began. Girls’ sports became an important issue for high schools.

MS. TIPPETT: So interesting to think about that not having been around.

MR. DONAHUE: Really. It’s really amazing and the drama continues, the tension continues.

MS. TIPPETT: Is it right that you put an abortion being performed on the show?

MR. DONAHUE: Yes, we did.

MS. TIPPETT: And then you invited the archdiocese and a number of people to discuss it?

MR. DONAHUE: Yes, and we showed them the film.

MS. TIPPETT: And that was at 10:30 on the weekday morning?

MR. DONAHUE: Now we aired in various times around the country.

MS. TIPPETT: OK, but it was a regular show. It was that day’s show.

MR. DONAHUE: Well, we taped the abortion.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, right.

MR. DONAHUE: And then, before we put it on, we called the people from the archdiocese. They came, we put them in a room and showed them the tape. And, of course, when it was over, I walked in the room and they were weeping and they were very concerned, because it looked so easy. I said, well, this is the procedure. And it’ s so easy that more people will get them. And I said, you know, this is an issue that is splitting families.

[Music: “Theturningbull” by Bexar Bexar]

MS. TIPPETT: You can listen again and share this conversation with Phil Donahue through our website, onbeing.org. There you can also subscribe to our podcast. Again, that’s onbeing.org.Although it is now a standard of every daytime talk show, Phil Donahue pioneered the audience-participation format. He was the first host to ever go out into the audience, making them part of the conversation. Here are some moments from a show he did in 1979, with Atlas Shrugged author Ayn Rand.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: I want to change the topic and go back to something you said about industry. Fifteen years ago I was impressed with you books, and I sort of felt that your philosophy was proper. Today, however, I’m more educated and I find that if a company …

AYN RAND: Excuse me, this is what I don’t answer.

PHIL DONAHUE: Well wait a minute you haven’t heard the question yet.

AYN RAND: She has already estimated her position and my work and incidentally displaying the quality of her brain if she says today she is more educated.

AUDIENCE MEMBER: I am more educated now than I was fifteen years ago when I was in high school since before I went to college and read the newspapers [inaudible].

PHIL DONAHUE: Let her make her point, let her make her point.

AYN RAND: I will not answer anyone who is impolite, but …

PHIL DONAHUE: She wasn’t impolite. You are equating someone who disagrees with you with impoliteness. That’s not fair.

MS. TIPPETT: Coming up…Phil Donahue on his personal transformations on race, gender roles, and parenting in the dramatic era he captured on television.

I’m Krista Tippett. On Being continues in a moment.

[Music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today with broadcaster Phil Donahue. His show was the original daytime talk show focused on issues, and he was a pioneer in audience participation. Oprah Winfrey has said there would have been no Oprahwithout Donahue. We’ve been discussing his remarkable lens on the social and political dramas of the late 20th Century. He’s recently guest hosted for Bill Moyers, and had a stint on MSNBC. Here’s an interview he did in 2002 with Nation of Islam leader Louis Farrakhan.

PHIL DONAHUE: Thousands and thousands of people…

LOUIS FARRAKHAN: Yes.

PHIL DONAHUE: Come to hear you speak, and I think I understand why. You speak to their anger. And, you know, it’s not possible to argue against the anger. 2,000,000 people in jail for every 100,000 people in prison — 35,000 are black, 1,100 hispanic, and 462 are white. When I hear you speak to these injustices, to these, you know, racial profiling — New Jersey state troopers.

Honestly, if I think I were a black male I’d be at Randall’s Island listening to you speak. I would. You know the political power that you have is undeniable. But you make it tough on the white reporters — with all this history of this kind of rhetoric, it’s awful tough to say, “hey Minister. Farrakhan sit down tell us how horrible we are.”

We have to challenge you as you would challenge us. This isn’t a game, this a matter of the respect that we want to have as professionals. You can’t get up there and talk like that as a man of God, using language like you do. So I am asking for some understanding here — you bring this on yourself.

MS. TIPPETT: It was just so honest and we don’t have honest public discussions in media or elsewhere.

MR. DONAHUE: I think I scolded him for not being respectful of Jewish mothers, for example, Jewish parents, devout Jews. You know, he called it the dirty religion. This was back when he was really quite offensive and I decided to challenge him on his absence of Christian empathy for the feelings that he was wounding deeply of Jewish people and others who lived their life around a faith.

So I do remember that part and I do remember saying that, you know, I get it. I’ve heard him speak, you know. “You don’t know your name!” he would say to a black audience, that their names were given them by white people, you know, Washington and Jefferson. And I recall being struck by the power of that and that I had never thought of that.

MS. TIPPETT: But, you know, race, for example, is something that we now bemoan right and left that we don’t know how to talk about even with a black man in the White House. I know that you resist being asked to be the person saying we did it so much better in the olden days, right? You don’t like to be in that role. But when you watch — I mean, you’ve talked about war in recent years in a way that got you into hot water.

But when you watch how we talk or fail to talk, to have the cultural reflection we need to have about something like race, you know, could you say how you might like to — how we might start it in a different place or does your mind go there? On race or something else? Maybe there’s something recently you’ve seen and you’ve thought I wish I could start the discussion here instead of there or weigh in in this way?

MR. DONAHUE: Mm-hmm. Well, isn’t that an interesting question. A lot of people, a lot of my friends, you know, we bused our kids to a Catholic school downtown to downtown Dayton. And I remember I went there the first time. The plumbing leaked in the little boy’s room and the paint was peeling. And in my suburban neighborhood where we lived, they had overhead projectors, they had pictures of Martin Luther King in history books in suburban Centerville.

And in downtown Dayton, there would be an [inaudible] of Cardinal Spelling and the pages were turning yellow. Everything was different downtown and we felt that Catholics were raising another generation of racists and we didn’t want that to be on our children. I began to realize what paternalism was too. I was on the board of — it was called the Dakota Street Center.

I remember very well that in the meetings of the board, the white guys did all the talking and I noticed that.

And then I remember when we needed furniture, I said, well, why don’t we go to Goodwill and one of the black board members said, hell, we give stuff to Goodwill. And I began to appreciate what paternalism was and how the white man will solve everything and a failure to respect the views even among the committed which we certainly were.

MS. TIPPETT: The enlightened, yeah.

MR. DONAHUE: And, of course, everybody in my own neighborhood, suburban Centerville, became convinced that we were gonna sell our home to a black family. So, you know, we went through that stage and I came to realize that there were really four — there were stages to commitment, you know. The first stage was the fun stage. You got a kick out of marching and it was also a messianic stage. Everybody was a bigot but you. You turned people off.

And then the third stage was a sudden overwhelming realization of the awesome challenge of the problem, that it was the Rock of Gibraltar and you were the feather. And that’s, I think, where the saints were made, people who kept on keeping on. I saw so many people just, you know, fabulous people to this day. They cared, but they did become exhausted. And a lot of people chose, you know, to fulfill this wonderful commitment that they stopped having. They took guitar lessons or yoga.

MS. TIPPETT: And did we kind of get stuck there culturally?

MR. DONAHUE: Some of us did, yes. And, yes, a lot of us are. The issue is hard to raise if it’s not immediate. Remember, this is a time when my first year on the air, Bobby was assassinated, the cops beat up the kids in Chicago, Martin Luther King was assassinated. Holy cow, this is the first year we were on the air.

And I made sure that our staff was integrated. I remember I hired the first black applicant, a female, and I’m embarrassed to say — I mean, one of the reasons I hired her is because she had the biggest Afro. But, I mean, this is one of the stages, you know, that we went through, or I did. You know, we were trying.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, I think even there’s something refreshing and helpful about you recalling things in that way because right now here in the 21st century there are a lot of problems which seem so huge. I mean, you look back at the 60s as a very fraught, you know, terrible time, but a time in which incredible social shifts happened. And that kind of shift is kind of unimaginable now and it’s not going to happen the same way. You’re kind of describing this like human wearing down, this very gradual, incremental.

MR. DONAHUE: Well, you know, sooner or later — black people saw the deterioration of their school system. They saw police brutality aimed at them and not white people. They saw joblessness. They saw their father pushed around by cops. And pretty soon, the cities exploded. And I think about that now. The gap between the rich and the poor has never been greater and getting wider. And I say to myself, how long can this continue without that explosion?

So in some ways, I think it’s hard, it’s hard to make a better metaphor. I wonder if we aren’t right now sitting on a powder keg especially on the matter of the horrible maldistribution of wealth, and the comfortable don’t really talk too much about that until suddenly they’re afraid to go downtown, because there are people in the streets.

[Music: “Lisbon” by Arms and Sleepers]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today: Phil Donahue.

MS. TIPPETT: Going back to that memoir you wrote in the 80s, I believe.

MR. DONAHUE: ’78.

MS. TIPPETT: The very first line of it, the very first words are “If I could start parenthood over again.” It was really striking to me that that’s where you began and, at that point, you were a huge celebrity. You know, your show was a huge phenomenon and you started it with your regrets about parenting.

MR. DONAHUE: Well, I came to realize, like so many others too late — too soon old, too late smart. We were raised at a time when people thought the worst thing you could do was spoil your children, you know. Kids have to know that life is tough and it’s filled with challenges and you have to make them tough, blah, blah, blah. It was like they were clay and you had to knead ’em and push ’em and create…

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Spank ’em.

MR. DONAHUE: Yeah, spank ’em. You know, I came to feel pretty guilty about this, again, guilt. On those occasions when my children pleased me, I didn’t say so. And now when I walk to Starbucks in the morning in New York City, I see mothers with their babies, some of them in a tram, stroller, and I see them, you know, kissing their babies. I love you, honey, you little baby. You’re so precious to me. And I thought to myself I never did that.

MS. TIPPETT: And you see fathers doing that too now.

MR. DONAHUE: And…

MS. TIPPETT: And you see fathers doing it too.

MR. DONAHUE: And fathers, yes. And I think to myself why didn’t I do that, you know? And why wasn’t I more — it’s such a more enlightened time now. Parents are more enlightened. Certainly, we have too many children today growing up without that kind of attention. So another reason for me wanting to start over again. But, you know, my kids all talk to me, so I’m…

MS. TIPPETT: Do they?

MR. DONAHUE: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: I want to ask you as the Catholic in you, what do you think of the new pope, of Pope Francis? I mean, you’ve been Catholic a long time and you actually did a show on Catholic clergy sexual abuse. When was that? In the mid 90s?

MR. DONAHUE: Very early, with my mother watching.

MS. TIPPETT: With your mother watching.

MR. DONAHUE: Well, I don’t know Pope Francis. You know, I admire the first step he’s taking. He’s doesn’t live up in the grand large rooms of the papal residence in the Vatican. That’s a good thing. Let’s not overdo it. But, you know, pope or no pope, the treatment of gay people in traditional Catholic teaching is itself a mortal sin.

You know, if the church believes they’re sinners, it makes it easier for me to beat them up.

MS. TIPPETT: Have you, over the years, developed a sense of God that is in contrast to that doctrine and theology that has come to make you so — that you’ve really rejected? That’s come to be so uncomfortable?

MR. DONAHUE: Well, Alfred Lord Tennyson speaks for me [laughs]. Lord Tennyson. I’ve gone from Immanuel Kant to Lord Tennyson [laughs]. It’s hidden in a poem titled “The Memoriam” which you can look up. Here’s what he said. “There lives more faith in honest doubt, believe me, than in half the creeds.” I read that and I thought, wow. I wish I’d roomed with you in college. You must have been interesting. And like, you know, I’m dangerous. I have a little knowledge. So that’s my little peek into Alfred Lord Tennyson just as I had only a glancing blow to “Prolegomena to Any Future Metaphysic”.

MS. TIPPETT: Kant, yeah.

MR. DONAHUE: But that speaks for me. I used to have fights with Madalyn all the time.

MS. TIPPETT: Madalyn O’Hair, yeah.

MR. DONAHUE: I would say, “Madalyn, you cannot tell a person that you’re absolutely certain there is no God and then, in the same breath, tell me that you’re absolutely certain…

MS. TIPPETT: That they can’t be certain there is a God.

MR. DONAHUE: Yeah. It’s a contradiction. You can’t do that. So agnosticism may be the only honest route here and keep your mind open. I mean, I am impressed with the universe. I look up at night and I go wow. You know, we can’t fathom this, their distances. The fact that every little pinpoint up there is a sun, a sun, except for our planets. They’re all suns. Carl Sagan said that on the air one day and I thought, wow, I never thought of that.

MS. TIPPETT: On your show?

MR. DONAHUE: Uh-huh. So, you know, the order, the orbiting, the novas and the great swirls that the new photography is bringing down to us, beautiful. The horsehead nebula, the sombrero, and there are things up there that just fascinate. And that the light that we’re seeing now left, what, 1000 years ago. I mean, that’s how long it took light to get here. Whoa! It’s hard for me to believe this is an accident.

But I’m having more and more trouble dealing with a commanding God — I’m having more and more trouble dealing with original sin. I’m not even asked to be born and I’m born with sin? I’m born with a sin? But if you don’t have that sin, then what do you do with Calvary? And, of course, I’ve been recently attracted to Sam Harris and…

MS. TIPPETT: Have you? I was just wondering. I was just thinking who would be guest on your show now with this line of inquiry?

MR. DONAHUE: Oh, him, for sure.

MS. TIPPETT: I think you’d have a lot of physicists on now too, some of the new physicists.

MR. DONAHUE: Right. You know, but it’s funny. Physicists lean more toward the possibility of a God than the life scientists do.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, they have a rich vocabulary of mystery, which is kind of what — or wonder, which is what you’re describing.

MR. DONAHUE: And, you know, I’ve come to know and really admire Ed Wilson, E. O. Wilson, of Harvard, the entomologist and sociobiologist. He’ll pick up a bug or maybe an ant and he’ll say this is a masterpiece. And, you see those legs all in unison propelling the main body forward, the swivel head, the antennae, there’s a brain in there, such as it is, a brain managing these various body parts.

And the more I get into it, and somebody said to me — these are all things that have come to me so late — you can take a Magellanic voyage around the trunk of a single tree. Oh, man. Now I know why I was so filled with wonder as a child when I was in the woods and saw that dappled sunlight and the brook and the water rolling over rocks and the sound it made and the things that scooted and skittered when I lifted a rock. And it’s only very recently, much later in life, that I realized this can be studied. We don’t know all the answers here.

As a child, I just thought that’s what it was, you know. Who made you? God made you. Sit down. I wasn’t encouraged to study it and that’s why the young people today have moved into the natural sciences and go out and get their socks wet walking through woods and their little notebook, you know. I’m so impressed with these people. They’re gonna save us all.

MS. TIPPETT: I think what you’ve modeled is study by conversation, you know, inquiry into daily life too. So I want to thank you as somebody who’s doing my part in that lineage.

MR. DONAHUE: Well, thank you.

MS. TIPPETT: It’s a real honor to meet you.

MR. DONAHUE: A pleasure, and believe me, there are many people out there who can carry this ball and, I mean, throw back answers that will just, I think, be a thousand times more inspiring, informed. You know, the people who got smart early, those are the people you want to talk to. Wow, they’re fascinating. I ought to know. I’ve met several of them on my own show.

MS. TIPPETT: OK. Thank you.

MR. DONAHUE: Thank you, Krista.

[Music: “Lake” by Emancipator]

MS. TIPPETT: Phil Donahue’s daily talk show, “Donahue,” aired from 1967 to 1996. He now writes and guest hosts, and produced and directed the documentary film, Body of War.

To listen again or share this show with Phil Donahue go to our website onbeing.org. And you can follow everything we do throughout the week through our weekly email newsletter. Just click the newsletter link to subscribe on any page at onbeing.org

On Being is Trent Gilliss, Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, and Mikel Elcessor.

We say farewell with this show to our intern, Megan Bender, a deep thinker and an old soul.

And special thanks this week to Tom Scott, Kate Brosnan, Jenelle Ferri and all the good people at the Nantucket Project, which is where I sat down with Phil Donahue.

[Music: “Ethnic Majority” by Nightmares on Wax]