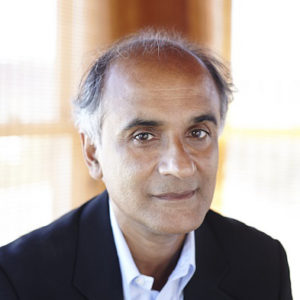

Pico Iyer and Elizabeth Gilbert

The Future of Hope 3

Pico Iyer is an esteemed journalist and essayist, and an explorer of inner life — for himself and in 21st-century society. For this episode in our Future of Hope series, he draws out writer Elizabeth Gilbert and “her sense of hope based not on a confidence in happy endings, but the conviction that something makes sense — even if not a sense that we can grasp.” Pico’s questions and Liz’s answers are all the more poignant given that both of them have recently suffered deep losses. These two friends delve into what it means to retreat into smallness, and grapple with a complex understanding of hope, as the world continues to overwhelm.

Image by Ifada Nisa, © All Rights Reserved.

Guests

Pico Iyer is the author of many books, including The Global Soul: Jet Lag, Shopping Malls, and the Search for Home, The Open Road: The Global Journey of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, and The Art of Stillness: Adventures in Going Nowhere. His latest is A Beginner's Guide to Japan: Observations and Provocations.

Elizabeth Gilbert is the author of beloved non-fiction books including Big Magic and the global sensation, Eat, Pray, Love. Her novels include: The Signature of All Things, and, most recently, City of Girls.

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: The one and only Pico Iyer is an esteemed explorer of inner life, for himself and in 21st-century society. He’s a journalist, novelist, and travel writer, who lives in Japan but used to retreat, many times each year, until the pandemic intervened, to a remote Benedictine hermitage. And here’s why he told me he wanted to draw out the writer Elizabeth Gilbert for this newest episode in our Future of Hope series.

He said, “One of the things that so moves and inspires me about Liz Gilbert is that she retains such brightness and optimism in the face of the many losses she so unflinchingly describes. When I spoke to her for a small library in Colorado last July, she seemed so at home with being alone, so cheerful and undistracted by the lockdown, even though she is usually such a gregarious and sociable being. How much is her sense of hope based not on a confidence in happy endings, but just the conviction that something makes sense — even if not a sense that we can grasp?”

In the conversation that follows, Pico’s questions and Liz’s answers are all the more poignant given that both of them suffered deep losses amidst our protracted pandemic realities. Liz’s life partner Rayya died of cancer, and Pico’s beloved mother passed away just before we were first set to record this interview.

[“Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Pico Iyer: We’re back in the realm of the small, and also the way that the body can teach us things that the mind could never grasp or would make overcomplicated. And I think all of us have found, during this pandemic, we have much less control over the external world than we imagine. It’s been a very good humbling for me. But we have much more control over how we respond to it.

Elizabeth Gilbert: And if there is one thing that I, if I had the chance to do it over again, could’ve done differently, would’ve been to walk into it in a stance of surrender — arms collapsed, no clipboard, no agenda, no cherished outcome — and to have almost gone limp into it, which is not the same thing as hopelessness, but it is a very powerful stance to take in the wake of something that is bigger than you are.

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.

[“Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

Elizabeth Gilbert is the author of books read around the world, including Eat Pray Love and the novels The Signature of All Things and, most recently, City of Girls. Pico Iyer’s cherished books include The Open Road: The Global Journey of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama and The Art of Stillness: Adventures in Going Nowhere. They’ve both been guests on this show in recent years, Pico on The Art of Stillness, and Liz on Choosing Curiosity over Fear. We brought them together via Zoom, the travel alternative of 2021.

Iyer: Liz, I am just so happy to see you again. Welcome.

Gilbert: I’m so happy to see you. I’m happy every time I get to see you or talk to you. Thank you.

Iyer: Thank you. This is a long time in the planning, in the making. And I remember, when you were on this program before, talking to Krista, as often she began at the very beginning, with your childhood growing up on a Christmas tree farm, I think in upstate New York, risking delight, which I’m sure is going to come back later today. And so I thought today it might be fun to begin at the other end, in other words, right now. How has the pandemic been playing out for you?

Gilbert: I’m just going to cut right to it and say, I think like many of us, I’m coming out of this pandemic transformed in ways that I would not have expected, didn’t think needed transformation, wasn’t looking toward. I found out some stuff about myself that I don’t think I could’ve found out any other way than by the world shutting down.

And where I am right now, geographically and literally, is in the small church that I’ve owned in rural New Jersey for the last 15 years but haven’t spent very much time in, because, like you, I travel and I don’t spend very much time anywhere. [laughs] But we all stopped traveling, and I’ve spent the last 18 months pretty much entirely alone — I mean, I’ve been with some friends who are here in the country, neighbors who I see on occasion.

I want to say there’s two sides of me on this, with the pandemic. There’s the public self, you know, who is — has been horrified and mortified and concerned and trying to help in ways that I can. But as a private individual, I discovered that spending 18 months alone is pretty great. [laughs] Pretty great, and I didn’t miss anything.

So I don’t think I’m going to live my life quite the same way after this. If anything, my soul is asking for more of it. And that’s not anything I would’ve expected. I was especially fearful of the winter of the pandemic, of the first winter, because I also have always had a lifelong fear of winter, growing up in a very cold, deliberately unheated house. [laughs] I hate being cold. And I discovered winter’s hidden beauties, which I think is a good metaphor for learning how to be by yourself. So it’s been — it’s been a remarkable experience.

Iyer: Yes. I mean, I think I’ve been thinking of this as the year of taking nothing for granted. And that’s led to two things: one, gratitude — here you and I are, able to speak in relatively good health after 17 months of isolation; and attention — looking at all the things I sleepwalk past in my regular life. I remember the last time I talked to you was July of last year, so 14 months ago. And you were telling me that, then, you were suddenly [laughs] appreciating the wonders of your home and saying, Hello, home. And you, as a traveler, were always — you used to be saying, Hello, world. Goodbye, home.

Gilbert: Goodbye, home. [laughs]

Iyer: Yes. And you know, I found the same thing. You know, just taking walks down the road from where I live, I see marvels as great as any I would travel to see in Tibet. And even your home environment probably has become a universe to you, and as glorious as any other universe.

Gilbert: And I’ve spent a lot of time making it nicer. I don’t mean renovating it, I just mean caring for it and seeing it as an extension of myself, and seeing that tenderness that I feel toward my home — gently closing a closet door, putting the shoes away — seeing a real simplicity of beauty in that.

But there were times, during the pandemic — and I walked the same walk every single day — where I thought, this is as beautiful as any place I have ever been in the world. I haven’t been to as many places as you have, but I’ve been to a lot of places. And these meadows and these woods and this stream and these simple birds, the sparrows and the hawks, and occasionally, a glamorous red-tailed hawk — or I saw a bald eagle one day, which feels extravagant for New Jersey, but they are here — are as spectacular as anything, anywhere.

And a friend of mine gave me a tip: to lower my standards [laughs] of gratitude, to lower the bar and to catch the low-hanging fruit so that it’s not — it doesn’t have to be these huge, epic, grandiose gratitudes. The more physical they are, the more I felt it in my body. My gratitude for these slippers that I have that have an insole that you can put in the microwave and you can warm up your feet, that’s on my gratitude list almost every day. And I feel it neurologically. Even when I say it, I remember how comfortable those slippers feel, and remembering that doesn’t necessarily send me into despair over the state of the world, and it starts to kind of rewire my brain. [laughs]

So my gratitude list, my gratitude practice has gotten simpler, you know, smaller. It doesn’t have to be spectacular, like — like all things that bring happiness. [laughs] Another small thing, nicely done.

Iyer: I was just going to say, we’re back in the realm of the small, and also the way that the body can teach us things that the mind could never grasp or would make overcomplicated. And I think all of us have found, during this pandemic, we have much less control over the external world than we imagine. It’s been a very good humbling for me. But we have much more control over how we respond to it.

I know that, a little before the pandemic, you lost the person you always call the love of your life, Rayya, painfully young, from cancer. And I’m wondering how that very difficult experience, if at all, has prepared you for what we’re going through now, living with what you can’t fix, I suppose.

Gilbert: Without a doubt. I’m going to come back around to Rayya, but where my mind instantly went, and I’m going to run with it, [laughs] is that I recently learned that — I’m fascinated, like many of us are, with the intersection of science and spirituality and where people are doing brain imaging and neurological studies on lifelong meditators and trying to see how different people’s minds — different people’s brains, not minds — different people’s brains operate, if they’ve spent a lifetime in contemplation. And they’re seeing these extraordinary differences between people; that the monks who they bring in to study don’t have a brain like yours and mine. It’s a landscape that they have cultivated over decades of sitting.

And when they do scans on people who we might, for lack of a better word, call enlightened, they discovered that there are two areas of the brain that have diminished almost to the point of not even registering anymore. And one is fear, and the other is the need to control anything. That is the major difference between — [laughs] there’s a lot of them, but that’s the major difference between me and an enlightened person, [laughs] is the need, the desire, the panicked terror, the wish to control anything or anybody.

This brings me back to my partner Rayya’s death. That was more humbling to me than anything I have ever gone through in my entire life. She had a terminal diagnosis. I was aware, at some level, that she was going to die. But I thought that I could curate that experience for her and for me: to make it pain-free, as pain-free as possible; to have as enlightened an experience of death as possible; to bring in the best teachers and guides and healers and hospice workers and — you know, I smile when I say this, because that is not at all how it went. [laughs]

I couldn’t control what pain and fear did to her mind. I couldn’t control the progress of the disease. I couldn’t control my own grief. I couldn’t control her family members and mine and the way that they acted out. I couldn’t control anything about the situation.

And if there is one thing that I, if I had the chance to do it over again, could’ve done differently, would’ve been to let go of that from the get-go — to walk into it in a stance of surrender, arms collapsed, no clipboard, no agenda, no cherished outcome — and to have almost gone limp into it, which is not the same thing as hopelessness, but it is a very powerful stance to take in the wake of something that is bigger than you are.

And because I didn’t do that, and because I fought for control, that situation was a great deal more stressful to both her and me than it needed to be.

And that again brings us to chop wood, carry water. What can you do? Well, I can do these small, daily tasks, and that’s about it. I can be as compassionate as possible to the people in my life without trying to manage them, without needing them to be different than they are. You know, the pandemic was a huge, chaotic crisis, but I’ve got people in my life who are also huge, chaotic crises, you know, walking — each person a walking vortex of nature: wild, uncontrollable, dangerous, [laughs] unpredictable, crazy, beautiful. And if I sort of see each person as their own embodiment of nature’s power, I can watch it with much more wonder than I used to try to control it with much more fear.

[music: “Softly Villainous” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, Pico Iyer interviews Elizabeth Gilbert for our series The Future of Hope.

[music: “Softly Villainous” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Iyer: I love when you used the word “granular” a few minutes ago, and the sense, really, of surrendering the notion of being enlightened or a good person or calm or the hero you’ve always wanted to be. And I find myself saying, often, to myself and to my poor friends, [laughs] during the pandemic, that this moment has only spotlit what is always the case. We’re always living in a state of uncertainty — two years ago, two years from now — and that therefore, part of our challenge as I see it is to make uncertainty our church in New Jersey — to make it our home. This is where we’re living, every day of our lives. And so, as you said, let’s rejoice in it, furnish it, close the door, rearrange the books, and say, Make this as beautiful as it can, given that forest fire, earthquake, or who knows what will be coming tomorrow — or tremendous beauty and love may be coming in the door tomorrow.

How, in the midst of this dance of turning fear into curiosity, where does hope come in for you?

Gilbert: I will say that I did — OK, I am showing off now, but I did look it up. There’s a line that I remember reading in the Tao Te Ching that says hope is as hollow as fear. And it’s in a similar passage that says success is as dangerous as failure — hope is as hollow as fear. And I always wondered about that line. I understand success is as dangerous as failure. I understand how disorienting those, both of those things can be, because both of them are wild swings that take you off the median of peace and have to be adjusted to. They’re adjustments in the norm, and people can get lost in there.

But “hope is as hollow as fear” — I remember reading that years ago and trying to understand it, and not understanding it because it seems like such an important thing that we, you know, that we would say, typically, and it is often said that we can’t live without it.

But how I understand that is that both of those, hope and fear, the reason that they’re hollow is that they both orient you toward imagining a future. And that is a fantasy. Imagining, fantasizing about an apocalyptic future is just as much of a fantasy as fantasizing about a utopic future. You’re still not here, in the present moment, because the realest, realest reality is, you cannot know. You cannot know what is coming. And you can hope, but you can’t predict.

And sometimes I think — I saw this with Rayya’s cancer. There were certain people in her life who simply would not give up hope that she was going to miraculously be healed from a completely deadly diagnosis where there wasn’t any hope in it. And people would bring stories to me of Anita Moorjani, who we know was on her deathbed from incredible cancer and then spontaneously healed. And these things happen in nature with no particular explanation, and so everyone was sort of holding onto “anything can happen at any moment.” And I saw people holding onto that hope even in the last three days of her life, when she was in a coma and her organs were shutting down.

And I don’t think you can take that from anybody, but what I did observe was, they weren’t there with her as much. And if I had been — if my fear about death and my fear about, how am I going to survive without this person? had me in a state of heightened hope, I wouldn’t have been able to be as absolutely present with her as I was, breath by breath, moment by moment, as this great being left the world. I would’ve missed that last presence. And that would’ve been a great shame.

So, lately, I’m less interested in hope, I have to say, as a — I’m trying to think — the things that I hope for now: I hope more and more to become a person who can live in the world as it is, whatever that is. That’s what I hope for. And that’s what I put my hours into, is the work that it takes to transform into that kind of a person. I hope to be a person who is less judgmental and more compassionate. And I work on that. [laughs] I really put in the hours. I hope to be a person who can — whatever I can change about my lifestyle to help the fight against global warming, I will, but without losing my mind to the fear of it. So my hopes have been reduced to very small, intimate wishes for transformations interiorly that will make me be able to move through whatever comes without adding to the drama, the pain, and the chaos.

Iyer: We’re back in the realm of smallness again. And I love that sense that hope gets in the way of the only treasure we really have, which is this moment, right now. As you know, my mother passed away just a few hours before we were due to hold this conversation. And I felt with that just as you did, I think, with Rayya, which is I was so glad to be fully there, not thinking about all the many ways she might be rescued or what would happen six months from now, but right there, as she’s drawing her final breath.

And it’s so interesting, what you said about favoring reality in some ways, which is what we have to work with — unknowable, the mystery of reality, rather than our projections upon it or our expectations.

At the same time, I’m guessing there must’ve been moments in your life where hoping actually allowed you, encouraged you to bring about something that might not have been possible before. I mean, you have a very positive outlook. And I’m wondering if there’s a moment you can remember over the years, where your hopeful temperament actually made things better than they might’ve been otherwise.

Gilbert: Yeah. [laughs] I mean, I think there’s a — how can I say this? Perhaps there’s a difference between hoping and dreaming. And I think hoping is kind of a willful inflicting — I don’t know why I have such a negative view of hoping. But I — I think sometimes — I’m just thinking of the T. S. Eliot poem, of “East Coker,” where he said, “I said to my soul, be still, and wait without hope / For hope would be hope of the wrong thing.” You’re hoping into the wrong reality, right?

But I think you — I think that there are only two things that I’ve been made aware of in the universe that are possibly infinite, and one is the universe itself, and the other is human imagination. And I have imagined my way and dreamed my way into really extraordinary transformations by being able to picture something that may come about if I — if I work toward it, you know, if I make that a priority.

I dreamed — I was going through — I’ve never been through as serious and grave and suicidal a depression — I hope never to again — as I did when I was going through my first divorce, when I was going through just massive — talk about the ground coming out from under your feet. I had stepped into a marriage with every expectation that my life would look just like my mother’s, you know, married at 24, two kids, stay with the same person forever. I certainly gave it a shot, right, because it was what I had been shown. It was the dream I had been given: this is what a normal life looks like. Now go do that.

And so I obediently went and did that, and I really came as close to death by my own hand as I’ve ever come, in that marriage, because that wasn’t — that was the wrong dream. [laughs] You know, that was not in accordance with my nature. It didn’t suit me. It more than didn’t suit me — I was dying inside of there.

And I ended up leaving that marriage, and it was not an easy divorce. Reality, in the form of my then-husband, made it even harder. And I was — and I left with nothing. I lost everything I’d been saving and earning my whole life, and — yeah, I left broke and broken.

And then I started dreaming about learning Italian. I just — I think it was that little spark in the right side of my amygdala that said, Want to create. Want to make something. Want to do something other than live in fear and despair. And that was the beginning of Eat Pray Love. It was a dreaming and an imagining of something pleasant, something that would be enriching, something that would be beautiful, and then that led me very accidentally into this life that I have now.

But remember that I also walked to the New School [for] Social Research and signed up for an Italian class, [laughs] you know, which is putting a little muscle behind it, you know? I think that dreaming requires action on your own part.

Iyer: In fact, the action is the important thing. When I was listening to you I was thinking, out of one’s head, into the world. One’s head is a small, dark, confused, probably not so exalted place. And the world, as we’ve been saying, is full of surprises and treasures, some of them scary, many of them not. You know, I always find the darkest moments in every day when I suddenly wake up in the dead of night, and I’m just lying in bed, and all the anxieties that you were talking about, all the insuperable problems just pile up unendingly in my head, and I think, how can I get through the next day?

And as soon as the light comes up and I’m out of my bed, I’m feeling like you walking towards the Italian class. I’m doing something. I’m moving forwards. I don’t have to be ruled by all the worries that I can generate in my head. I can in some ways give myself up to the uncertainty of what’s coming, but just move, act, be in the world and not in tiny Pico, who’s only going to make a mess of the world most of the time.

Gilbert: I have a rule, Pico, against — sorry, just before I forget it, I have a rule, very strict rule in my life against horizontal thinking, which means if I’m in bed — because I wake up, my mind turns on, and the anxiety begins. And I call that horizontal thinking. My mind has me trapped in bed, lying down, and so it can do whatever it wants. It can have its way with me. And so sometimes just getting vertical, you know — like I battle against horizontal thinking by actually standing up, and now I can do vertical thinking. [laughs] And vertical thinking is already better than horizontal thinking. [laughs] So sometimes it’s just the physical activity of changing your posture from down to up. [laughs]

[music: “Dusting” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: After a short break, more with Elizabeth Gilbert and Pico Iyer.

[music: “Dusting” by Blue Dot Sessions]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, in a new episode of our Future of Hope series, the journalist and explorer of global life and inner life, Pico Iyer, drawing out someone he admires, the writer Elizabeth Gilbert. In addition to her global sensation Eat Pray Love, she’s the author of Big Magic, a book about creativity, her novels include The Signature of All Things and, most recently, City of Girls.

Iyer: I’m wondering — I mean, everyone asks you this, because you always have a good answer. What are your daily practices that help you, maybe, keep the wrong kinds of dreams and hopes away and keep you where you need to be?

Gilbert: Well, my foremost daily practice is something that was born out of emergency in my life. And I feel like I’ve spoken with you about this before, but I’ll share it again, which is that I write to love, every day, and I ask love to write back to me. And so this is actually really simple, [laughs] and anybody can do it. I’ve been doing it off and on for the last 20 years, and for the last two years, I would say religiously, I’ve been doing this, because I realized that I’m really not OK without it.

And where it was born was that I was in the middle of my divorce. I was in great despair. I was in hell and in loneliness and sorrow and terror, in the middle of the night. And I don’t know where the inspiration came from, but I thought, what would — if I could generate somebody who would say to me the things that I’ve always needed to have somebody say to me, what would those things be? And I grabbed a notebook, and I wrote a letter to myself from that.

You know, and at the time, I didn’t know what it was. But now I — for shorthand, I call it “Love” — capital “l,” Love — really, divine love. And I just — it was such an easy exercise to do, because it didn’t take me very long to know what it is I’ve always wanted to hear somebody else say to me. And it is: I love you. I am with you. I will never leave you. You are not alone. I’ve got you. You are my precious. You are my beloved. You are my child. There’s nothing you can do or not do that could cost you this great love that I have for you. You — I don’t need anything from you in return. I don’t need you to provide anything for me; I don’t need you to prove anything to me. You don’t have to feel better, for me to love you. You don’t have to stop crying, for me to love you. You don’t have to be successful at anything, for me to love you. Nothing is owed, nothing is earned, nothing is asked.

And even though I was the one technically writing these words, it worked to settle my nervous system. I don’t think my brain was — I don’t think the fear part of my brain was sophisticated enough to notice that I was the one writing it. All it heard was, You are safe, you are loved, you are mine. You can’t fail. You can’t disappoint me.

And I remember beginning to do that practice, and there were times when I would say — I would do a dialogue with that voice. And I would say, What should I do? I am so frightened. What should I do? And it’s funny that you mention, get up and get a glass of water, eat a grape. Very seldom does love have anything for me but the most simple, what you can do in the next five minutes advice. And when I ask love what’s going to happen, what’s going to come of us, what’s going to come of the world, what’s going to come to me, love always says, I don’t know. That’s not my department. [laughs]

Iyer: [laughs] Beyond my paygrade, yes.

Gilbert: Beyond my paygrade. I’m not — I am not God. I’m included in God, I’m part of God, but I’m not God. I don’t have access to that. But I’ll tell you this — I’ll be with you. I’ll be with you no matter what it is. You can’t lose me. And we’ll do it together, as I’ve done everything with you, together. But in the meantime, I would suggest getting up and getting a glass of water.

So it’s this tremendously tender and merciful force, and if there’s anything that I feel like is absolutely absent from our culture, it is mercy and tenderness. And so to reverse the pressure of what contemporary life is with mercy and tenderness, I do think it actually changes me.

Iyer: Yes. And it’s always struck me — I think you are unique in my experience, in the sense that I associate you with talking to hope, talking to fear, talking to the muse, talking to supreme intelligence or the divine. As you were saying, that moment in Eat Pray Love when you were broken apart, I think you got down on your knees, and you spoke to whatever is out there.

And I think I also remember your writing, maybe saying, that when you were very young, you made a promise to the writing gods [laughs] that you would write probably every day of your life going forwards, whatever happened to the writing, whatever success or failure came to it. And so a part of me, the selfish part wants you to open the notebook and tell us, how has writing helped you deal with everything that life throws at you?

Gilbert: It’s my — it’s my portal. I’ve felt, for most of my life, that there’s something that longs to be in contact with — with us; with me, certainly, as much as I long for it. It’s a tension that goes both ways. It’s a — I think the Sufis called it a harp string: you pluck one side of it, and the resonance is felt on the other. You pluck that side, the resonance is felt on the other. I feel very strongly that there’s an intelligence in the universe that wants to communicate with us, and I think that it tries to find us in however we are most — that we can most find it.

So I have friends who are incredibly kinesthetic. I’ve got a friend who’s an extraordinary dancer, and she feels it when she dances. And writing has always been that for me. Writing was my first prayer. And now it’s become the place where I pray. I pray on the page, and because I’ve always felt a thing calling me to do it and wanting to engage in this with me and wanting to teach me how to do it and wanting to — wanting me to listen to it and wanting me to cooperate with it, rather than fight it. So yeah, writing has brought me my God.

Iyer: I think writing has made me believe, much more than I would otherwise, because things come out of me or out of the air [laughs] I would never have guessed were there — I mean, small miracles all the time. And they make a sense that my mind could never construct. You know, maybe I would write something about what we’re talking about today, and a week later something happens that speaks exactly to what came out of my subconscious, which is far wiser than I could ever be.

But one way or another, it’s a way of suggesting that there are patterns that are at work in the world beyond any that we could begin to grasp or explain, which is a comfort, given that you and I have been talking about uncertainty, and there are these challenges that are putting us in place and that we never saw coming, and these beautiful intricacies, too, and an order in the world that we never imagined.

I mean, when I think about hope, one of my favorite phrases has always come from the sort of philosopher-king Vaclav Havel — you know, the amazing thing, a writer who suddenly, seven weeks after being in prison, became president of his country. And I think he said something like, Hope is not the conviction that everything will turn out right, because it usually doesn’t. It’s just the notion that there is an order to things.

And we’ll never know what it is, and we’ll never know why Job keeps protesting his love and gets punished for it again and again, or why children get cancer when they’re two years old — all of this, we can’t understand or explain away. But hope is the sense that there’s something else there that has a plan or has a logic that we wouldn’t be able to sense. And somehow, even that can make us feel better, whether you call it God or the intelligence. It’s just that there’s something out there [laughs] and that the world isn’t left in the hands of tiny Liz and tiny Pico. It’s a comfort.

Gilbert: Even though we would do great at running it.

Iyer: [laughs] Running — yes, let’s run for president.

Gilbert: [laughs] If everyone would just do what we said … as we all think.

There’s a wonderful Stephen Mitchell passage where he writes about Jacob, and — Jacob in the Old Testament, encountering a stranger in the night and realizing that it’s an angel and then wrestling with it until daylight. And Stephen Mitchell writes this beautiful passage about what happened to Jacob as he became older. And this is sort of in Stephen’s envisioning of it: By the end of his life, he found that he wanted nothing but what God wanted. He wanted nothing but what God in all grace had already given.

If you take out “God” and replace it with “Tao,” it’s a very similar idea, you know? I don’t want anything but what the Tao wants. What is the Tao? If you take out “Tao” and replace it with “reality,” I don’t want anything except what reality wants. You know, those are all interchangeable ideas, the way, the path, the Taoist idea that wood is split more easily if you split it along its — along its grain, rather than against.

That doesn’t mean that I can’t join with people who are working to improve the lives of other people and add my energy and my voice to that, because that feels like what the Tao wants. [laughs] You know, that feels like what the way is. That feels like what the universe is asking for — more of this, less of that; more of mercy, less of condemnation; more equality, less injustice. So why wouldn’t I add my energy to that field?, you know, because actually, not to do that would be harmful.

So that’s what I go to. I actually have that quote on my refrigerator, of, “He wanted nothing but what God wanted, nothing but what God in all grace had already given.” I mean, that’s the — what possible more serenity could you have than that? And if I hope for anything for myself, personally, it’s to learn how to do that. If I hope for anything for the world, it’s that we learn how to do that.

Iyer: I also think what you were just saying is almost an explanation of what growing up is all about, which, to me, is about seeing [laughs] that my ideas of the world are always going to be much less rich, deep, and surprising than the world itself. And I remember, as a kid, and maybe like many of us, a pandemic would arrive, and I would say, “This is a horror,” rather than seeing that there might be an opportunity as well as a loss contained in it. And then I would maybe dream of, as you did, writing a book that sold a million copies and thinking, This is wonderful, not realizing that there are traps within success as much as in failure, as you saw it.

And I think as we’re talking about hope, I’m getting the sense that a large part of it is surrender, which is a surrendering of our hunger for explanation or our need for ideas or our sense that we’re on top of the world — because we’re usually on the bottom of it — [laughs] and also, therefore, about humility. You know, I’m always very moved every time I see Pope Francis speak. He goes right through me. I can almost feel a sense of compassion. But what completely knocks me out every time is at the end, he’ll say — he’ll look plaintively at his audience and say, “Please pray for me.” In other words, I’m just another suffering human being at the mercy of who-knows-what. I’m not the guy running the world or even, probably, running the church. I’m just — you know, “Please pray for me.”

And I think Catholics often say that, but whoever you are, just ending with that, when you’re a person that others look to as a voice of authority or wisdom, is one of the most moving things you can offer, because he’s essentially extending a hand. You know, I will pray for you, but please, please, pray for me. I’m Pope Francis, and nonetheless, my life is not so easy, and difficult in ways you could never begin to imagine.

Gilbert: It’s beautiful.

[music: “Basketliner” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, Pico Iyer interviews Elizabeth Gilbert for our series The Future of Hope.

[music: “Basketliner” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Iyer: So I think — I mean, we’ve been talking a lot about humility, I’d say, and giving up our agendas, but also our thoughts of control, throughout this. As we begin to near the end of this, really my favorite surprise among all your works is your novel The Signature of All Things. And in it there’s a character who says, I think, something like, “On the whole, I see more wonder in the world than suffering.” Would Liz Gilbert say the same thing?

Gilbert: You know — for people who aren’t suffering in the moment, suffering is always a philosophical construct. [laughs] And I’m not suffering in the moment, so it’s a really easy thing for me to sit here in New Jersey, in good health, as an artist of great privilege, as an American, as a white person, and say, “Yeah, world’s full of wonder, [laughs] and there’s more of that than suffering.” I wouldn’t say it in the presence of — of somebody whose child is in the oncology department, whose country America has just pulled out of and they’re desperately trying to get their family to safety. You know, I think we have to be careful not to use that idea as a weapon against those who are currently in pain. And I will say it only in context of my own suffering.

My dear friend Suleika Jaouad, who just wrote this amazing book, Between Two Kingdoms, about having cancer in her 20s, just posted something about how platitudes can be so hurtful to people who are in pain and how, when she was waiting for a bone marrow transplant and missing her entire youth to leukemia, to have people casually say, “Yeah, it’s all part of the great web of things,” or, God help you, even worse, to say, [laughs] “You must’ve done something in your past life to bring this on,” or, “It’s all for a reason” — you know, it’s so cruel.

And yet, when we do suffer and we come through it, oftentimes we can’t help but see where there was something in that suffering that had to happen. My friend Rob Bell has a great exercise he does with people on this where he says, Imagine there are two whiteboards, one on your left and one on your right. And the one on the left says: Suffering. Failure. Despair. The one on the right says: Joy. Success. Happiness, or love. And you ask yourself, what do you want your life to be filled with? Of course, we all strive to keep ourselves on the side of joy and success and love and happiness. You want that for yourself, you want that for your loved ones.

But then he asks, If you were to ask yourself, what are the three events in your life that most forged you into the person who you absolutely feel you needed to become and that you could not have become any other way, which whiteboard did they come off of? Where was the furnace, the crucible that brought you into being, of who you are today? And it’s the misfortune. It’s the loss. It’s the failure. It’s the addiction. It’s the rug being pulled out from you, as our friend Stephen Mitchell says, again: first they pull the rug out from under your feet, then they pull the floor out from under the rug, then they pull the ground out from under the floor, and now you’re getting somewhere. You know?

And somehow, if you can survive that, you come out on the other end. And you can’t quite bring yourself to want to say, “I’m glad it happened,” because it was awful; you would never wish it on anybody. You would never, if you were a compassionate person, say to somebody who was going through it, “Oh, you’ll be really happy when this is over, at what it turns you into.” And yet something interesting is happening here. You are growing into something more subtle, more elegant, more kind, more human than you might’ve been without it — certainly, more capable of empathy.

So is the world more full of wonder than suffering? I would say that sometimes suffering is actually part of the wonder, the tool of suffering and what it can turn you into. And that, too, I think, is part of the wonder of being here in Earth school. It’s not an easy school.

Iyer: I think if I were to define you in one phrase — which, of course, is something I should never do. [laughs] But what I would say, first, might be “friend to the world.” I mean, I feel that you’re an unusually openhearted person, but tremendously discerning, too, because that’s as important as the compassion part. So maybe we’ll just end by saying I’m sure so many people, your readers, your friends on Facebook, your friends across the globe, have turned to you during this very difficult period and asked you, “Liz, what should I do? How can you help? What’s the best way of living through this moment?” And I wonder if you could tell us what you’ve been saying to them.

Gilbert: I would say — first of all, thank you for saying that. I do love the world, Pico. [laughs]

Iyer: [laughs] I noticed.

Gilbert: And I do love — [laughs] this is what they say of some people: love humanity, hate some individuals. But I find hate very hard to sustain. It’s not my natural state. I really do — I really do love us.

I would say, you don’t have to get this right, you know, first of all. You don’t have to nail this. You don’t have to ace this. No one is expecting you to come through this like a champion. Especially, I’m thinking of the people who are on the front line of the pandemic, or people who’ve got small children at home and huge pressures, people who lost their jobs, people who lost family members. If grieving is what is required, then grieve. You don’t have to hold it together.

As much as you possibly can, be a gentle steward of your own experience here on Earth. The transformation in my life that has been the most important was turning my opinion of myself from hostility to friendship, offering myself a loving hand of friendship and saying, I don’t know for sure who else I’m supposed to be taking care of — that sort of changes by the day, based on what’s happening in the world and who’s coming in and out of my life — but the one thing that does appear to be inarguably true is that something gave me this one. I’m pointing at my own chest. Something gave me this one to look after in this lifetime.

I like to think that they gave me this mind because they thought that I would learn how to navigate it as best I could sail its choppy waters. I have a very difficult mind to manage. I have a very high-anxiety mind, and I’ve spent most of my life trying to learn how to sail it, how to sail it through its difficulties. And I’m learning from a spirit of friendship toward it.

It’s not how I was raised. I had to learn that. It’s not what I was taught. It’s not what my family taught. It’s not what my culture taught. But I feel very fortunate that somewhere in me, in my soul, there was enough of a compass to say, the only thing that’s going to get you through this is loving friendliness towards yourself and everyone.

Just treat yourself decently. [laughs] And it makes it easier to treat others decently, as well. [laughs] And good luck. Good luck.

Iyer: Thank you, Liz. Thank you for your words today, and your books in so many places. Thank you for your being.

Gilbert: And yours, Pico. I love you very much.

Iyer: Thank you.

[music: “Gambrel” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Tippett: Pico Iyer is the author of many books, including The Global Soul: Jet Lag, Shopping Malls, and the Search for Home; also, The Open Road: The Global Journey of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama and The Art of Stillness: Adventures in Going Nowhere. His latest book is A Beginner’s Guide to Japan: Observations and Provocations.

Elizabeth Gilbert is best known for her well-loved non-fiction books Eat Pray Love and Big Magic. Her novels include The Signature of All Things and, most recently, City of Girls.

I’ve interviewed both of them previously for this program, and you can find those shows at our website or in your podcast feed: The Urgency of Slowing Down, with Pico Iyer, and Choosing Curiosity Over Fear, with Elizabeth Gilbert. Pico also interviewed me on this program, about The Mystery and Art of Living. Again, find all of that at onbeing.org.

[music: “Under the Sun” by Shawn Lee’s Ping Pong Orchestra]

The On Being Project is: Chris Heagle, Laurén Drommerhausen, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, Suzette Burley, Zack Rose, Colleen Scheck, Julie Siple, Gretchen Honnold, Jhaleh Akhavan, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Ben Katt, Gautam Srikishan, Lillie Benowitz, April Adamson, Ashley Her, Matt Martinez, and Amy Chatelaine.

The On Being Project is located on Dakota land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear, singing at the end of our show, is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent, nonprofit production of The On Being Project. It is distributed to public radio stations by WNYC Studios. I created this show at American Public Media.

Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org;

Kalliopeia Foundation, dedicated to reconnecting ecology, culture, and spirituality, supporting organizations and initiatives that uphold a sacred relationship with life on Earth. Learn more at kalliopeia.org;

The Osprey Foundation, a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives;

The Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development, and education;

And the Ford Foundation, working to strengthen democratic values, reduce poverty and injustice, promote international cooperation, and advance human achievement worldwide.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.