Rafiq Kathwari

Mother Writes to President Eisenhower

Would you write a letter to a world leader? Do you think they’d listen? What would you say?

We’re pleased to offer Rafiq Kathwari’s poem, and invite you to sign up here for the latest from Poetry Unbound.

Letterpress print by Myrna Keliher. Photography by Lucero Torres. © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Rafiq Kathwari is the first Kashmiri recipient of the Patrick Kavanagh Award. He obtained an MFA in Creative Writing at Columbia University and an MA in Political and Social Science from the New School University. Rafiq divides his time between New York City, Dublin, and Kashmir.

Transcript

Transcription by Heather Wang

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and I started writing letters when I was five or six, I suppose, letters of thanks to aunties or somebody who’d given me a present. Letters are extraordinary, because they are usually handwritten, and so they bear witness to time, and the body of the person who held the pen or the pencil and wrote it and put it in the envelope and sent it. And letters, too, bear witness not just to thanks and gratitude or the exchanging of pleasantries, but letters bear witness to what it’s like to live through Partition, to what it’s like to tell the truth from a personal point of view, about terrible things that are happening in a community, and to detail those alongside all the pieces of information about your family that you’d include in a letter.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Mother Writes to President Eisenhower” by Rafiq Kathwari:

“6 August 1956

“Dear Mr. President,

“I’m your shadow under the Kashmir sky.

My 7- and 9-year-old boy and girl

are over there across the Cease Fire Line

and my younger four are with me

over here on this side of Partition.

“Children who grow up apart don’t know

how to say goodbye.

Gods of wrath have flung me

into an unloved city where flowers are dusty,

and branches are weeping.

“Even birds have stopped singing.

My home feels empty. Why

can the blessed nuns at Jesus & Mary

Convent, Murree readily cross the Line

to teach at the Presentation Convent,

“Srinagar, and my children can’t? Gods

of wrath are killing my memory.

A mother without memory has no history.

I shield myself with silence.

A voice speaks inside my heart. Often,

“I wish to make myself wings, and fly.

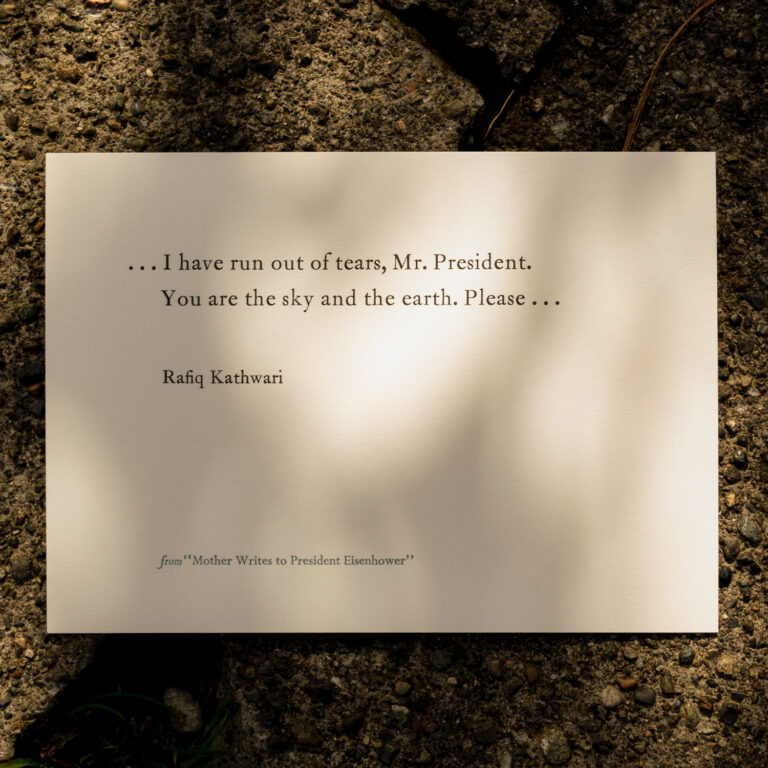

I have run out of tears, Mr. President.

You are the sky and the earth. Please

tear down all walls dividing people,

not just in Kashmir but wherever

“children become barricades. Please

show the world our resolve

by printing this in The New York Times.

Good luck in your bid for re-election.

I’ll pray for your victory. Sincerely,

“Mrs. Maryam Jan,

Muzaffarabad,

Pakistan-administered Kashmir.”

[music: “Ice Tumbler” by Blue Dot Sessions]

So even without knowing much about the history of Kashmir or the history of Rafiq Kathwari’s family, so much is evident in this poem, and the poem itself becomes the text that informs, as well as reflects. There’s a sense that Kashmir is seeking attention on the world stage, here, and that America is seen as a potential help, if only by his mother, who is writing to President Eisenhower. In the line “Please / show the world our resolve / by printing this in The New York Times,” there is the echo of people from so many places of conflict, which is to say, Don’t forget. Pay attention. Keep our news in your news. Be with us in solidarity, by raising voices, by raising awareness, by not forgetting.

And separation is everywhere in this poem, and this poem really is a poem about Partition, but not just partition of a country, and not just partition of a family. There’s the separation in the “me” and the “you” of the poem — the mother writing to President Eisenhower; and then there’s the separation of her from some of her children; and the separation of siblings from siblings; and the separation of time, as well, wartime and peacetime. And in wartime, even the birds stop.

And then there’s the separation of people who can’t cross a borderline, and the people who can. Those nuns from the convent can, but Mrs. Maryam Jan can’t.

And then, finally, there’s the sense of the separation of herself from herself: “A mother without memory has no history.” You can hear the fracturing, the fragmentation of her own self, in this poem. It seems like her voice and her personhood is being partitioned in the same way that Kashmir has been, and that in the no-man’s-land of this experience — the back-and-forth of your own country, of your own region being up for grabs in the partitioning of India with Pakistan — in the context of that, that dividing line runs through her body, too.

[music: “Every Place We’ve Been” by Gautam Srikishan]

The format of this poem is an age-old format; it’s a letter; and a letter always has a hope of being read. But most letters that are written are written in order to get a response. Putting something down on paper also bears witness. It bears witness to the truth, it bears witness to feeling, and it bears witness to the body that’s writing it. In the intimacy of the writing of a letter and the setting of that letter as a poem, we see how the deep desire for solidarity and the cessation of war is present in this letter that’s being written.

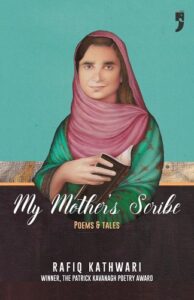

The poet, Rafiq Kathwari, has written a letter in the style of his mother. And this whole book is called My Mother’s Scribe, and when he was younger, he was his mother’s scribe. And in a certain sense I always find myself wondering, as I read this book, are some of the poems that he writes in the hand of his mother, are they recollections? Are they poetic inventions right now? Are some of them from an original source? Maybe there’s copies of the letters that were kept.

I don’t know the answers to any of those things, and they’re left in suspension for us. We find ourself floating around the blank space of the poem, wondering, who really wrote this? His mother, himself, something in between them? She only died, at the age of 96, in 2020, just at the beginning of the pandemic. And this poem has been around for a while, and in it what we hear is the space between him and his mother being given voice, him writing in his mother’s voice, just as in the way he wrote in his mothers’ voice to his mother’s dictation when he was a boy.

[music: “Ashed to Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

There’s an extraordinary reportage in this poem, where details about who is and who isn’t allowed to cross, where the Presentation Convent is, which nuns from what convent can cross the border into a convent on the other side of the border. And then at the same time, there’s the elevation of the music of language, too: “I have run out of tears, Mr. President. / You are the sky and the earth. Please / tear down all walls.” The deep desire for practical action is met with the music of lament, in the context of this poem, and joining lament with beauty and joining detail with pure prayer and pure plea is happening the whole way throughout this poem.

There’s also striking and unforgettable detail about the individual experience of being on one side of a line of partition when some of your children are on the other side, and that siblings are partitioned, and that a mother is looking at her partitioned family and her partitioned children: “Gods of wrath have flung me / into an unloved city where flowers are dusty, / and branches are weeping.” And then later on, “Gods / of wrath are killing my memory.” Her body is the situation of Partition, as well as the land. And Kashmir here is weeping through her, and her voice has become the embodiment of separation.

These details are true in Rafiq Kathwari’s family. His family were split apart, and some of the siblings didn’t see each other for many years later. And, at the same time, while this is true for his family, it’s also true for what he’s speaking about in the voice of a place; Kashmir.

[music: “Vally VX” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Much of this whole book is about Rafiq Kathwari’s mother and her experiences of Partition, but then the way that Partition really did affect her personally, and affect her mental health. And her life was really severely and powerfully affected by separation. In the context of somebody who did live with the severe impact of an affected mental health after war, one of the things Rafiq Kathwari does in this brilliant poem is to give her clarity, because I think it could be so easy for somebody to say, Oh, you don’t need to take the letter of somebody who’s writing to the American president, who themselves is living with a sense of mental unwellness after war — you don’t need to take that seriously.

And he’s saying, Yes, you do, because this letter is brilliant. It diagnoses the problem and the consequences; it has a clear ask and a direct address and practical suggestions, and builds upon the idea of a coalition of alliances, as well, across the world, and, in the midst of that, has reportage, personal narrative, lament, and pure poetry — the music of language. And by putting all these together in this brilliant poem, he is saying that the impact on his mother’s mental health as a result of Partition, that impact must not be used as a way to silence her. Her voice is restored to us and to him and to the world, through this poem. And by doing so, I think he’s inviting us to pay attention to all the other voices that it can be easy to consider silencing, as a result, perhaps, of not liking the medium of their communication or as a result of thinking, oh, they’re just distressed because of the war. He’s saying, Yes, they are; and listen.

[music: “Memoriam” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Mother Writes to President Eisenhower” by Rafiq Kathwari:

“Mother Writes to President Eisenhower”

“6 August 1956

“Dear Mr. President,

“I’m your shadow under the Kashmir sky.

My 7- and 9-year-old boy and girl

are over there across the Cease Fire Line

and my younger four are with me

over here on this side of Partition.

“Children who grow up apart don’t know

how to say goodbye.

Gods of wrath have flung me

into an unloved city where flowers are dusty,

and branches are weeping.

“Even birds have stopped singing.

My home feels empty. Why

can the blessed nuns at Jesus & Mary

Convent, Murree readily cross the Line

to teach at the Presentation Convent,

“Srinagar, and my children can’t? Gods

of wrath are killing my memory.

A mother without memory has no history.

I shield myself with silence.

A voice speaks inside my heart. Often,

“I wish to make myself wings, and fly.

I have run out of tears, Mr. President.

You are the sky and the earth. Please

tear down all walls dividing people,

not just in Kashmir but wherever

“children become barricades. Please

show the world our resolve

by printing this in The New York Times.

Good luck in your bid for re-election.

I’ll pray for your victory. Sincerely,

“Mrs. Maryam Jan,

Muzaffarabad,

Pakistan-administered Kashmir.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Chris Heagle: “Mother Writes to President Eisenhower” comes from Rafiq Kathwari’s book My Mother’s Scribe. Thank you to Yoda Press, who gave us permission to use Rafiq’s poem. Read it on our website, at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, and me, Chris Heagle.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions.

This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. You may enjoy our other podcasts: On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me. Find those wherever you’d like to listen, or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.