Reginald Dwayne Betts

Essay on Reentry

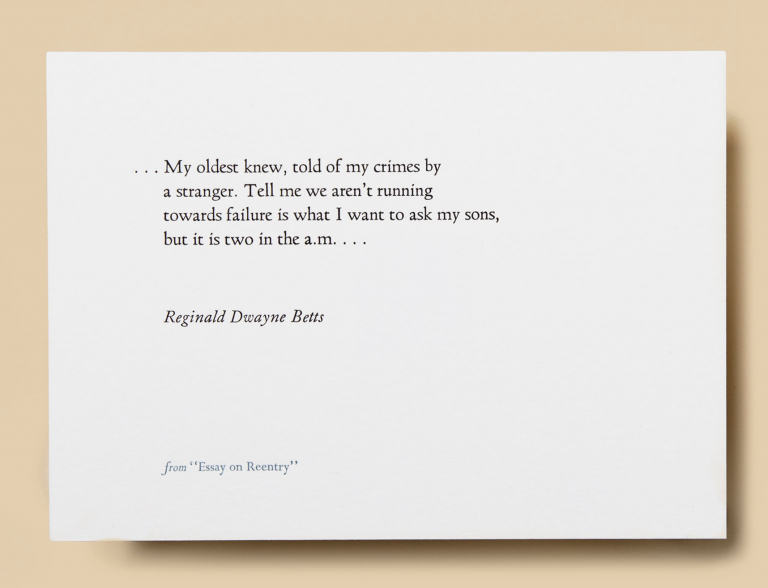

This ‘Essay on Reentry’ charts life after prison: and the way that others keep your sentence alive even when you’re wishing to just get on with your own life. It’s about secrets and choice and disclosure. And in the midst of all this, there is also love between a son and his dad, a son like a “straggling angel, / lost from his pack finding a way to fulfill his / duty.”

Letterpress art by Myrna Keliher.

Image by Lucero Torres, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

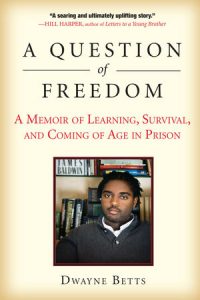

Reginald Dwayne Betts is the author of a memoir and three books of poetry. His memoir, A Question of Freedom: A Memoir of Learning, Survival, and Coming of Age in Prison, was awarded the 2010 NAACP Image Award for non-fiction. His books of poetry are Shahid Reads His Own Palm, Bastards of the Reagan Era, and Felon. He is a graduate of Prince George’s Community College, the University of Maryland, the MFA Program at Warren Wilson College, and is currently a PhD student at Yale Law School.

Transcript

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and one of the things I love about poetry is how it can collapse so many different things that happened in your life, across different periods of your life — the past, the present, and the future even — into one poem. And in this way, you’re facing the pain of yourself from the past, and hopefully the increasing healing of yourself now, and the person you want to be, and the person you will become. And all of those are in some kind of conversation with each other. It doesn’t make it easy, but it does make it powerful.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Essay on Reentry” by Reginald Dwayne Betts:

“At two a.m., without enough spirits

spilling into my liver to know

to keep my mouth shut, my youngest

learned of years I spent inside a box: a spell,

a kind of incantation I was under; not whisky,

but History: I robbed a man. This, months

before he would drop bucket after bucket

on opposing players, the entire bedraggled

bunch five & six & he leaping as if

every lay-up erases something. That’s how

I saw it, my screaming-coaching-sweating

presence recompense for the pen. My father

has never seen me play ball is part of this.

My oldest knew, told of my crimes by

a stranger. Tell me we aren’t running

towards failure is what I want to ask my sons,

but it is two in the a.m. The oldest has gone off

to dream in the comfort of his room, the youngest

despite him seeming more lucid than me,

just reflects cartoons back from his eyes.

So when he tells me, Daddy it’s okay, I know

what’s happening is some straggling angel,

lost from his pack finding a way to fulfill his

duty, lending words to this kid who crawls

into my arms, wanting, more than stories

of my prison, the sleep that he fought while

I held court at a bar with men who knew

that when the drinking was done,

the drinking wouldn’t make the stories

we brought home any easier to tell.”

[music: “Every Place We’ve Been” by Gautam Srikishan]

One of the things that speaks to me in the poem is the question about identity. And in this poem, the speaker of the poem, the poet, Reginald Dwayne Betts, all of these identities are being put forward for him: a man, a man who’s been out with friends, a father, a son, a man who did one thing for which he was punished, and a man who lives with ongoing punishment in the question of reentry and a sentence and a story that follows him around, a man who’s interested in sports and interested in coaching, and clearly, because he’s writing poems, he’s interested in literature, and a man who is awake at night, and a deep tenderness and a sense of lamenting, and a man who is both alone and profoundly in tender contact, and a man, also, who is considering the way within which time plays itself out. And he is writing as a Black man who has served a custodial sentence, and writing in a critiquing way about a prison structure that is so leant towards incarcerating Black men.

[music: “Every Place We’ve Been” by Gautam Srikishan]

There are so many scenes in this poem. And this can be a really helpful way, sometimes, to look at a poem and to break it down into scenes, almost like it’s a film. That doesn’t work with every poem, but it really works with this poem. And in this, the character of time is really present. So the first scene: a man’s awake at 2 a.m. His son’s next to him, and the cartoons on the television are being reflected in the eyes of the son.

And then the next scene goes just back a little bit in time to the poet, who’s at the bar with some other fellas. And then it goes back earlier, much earlier, and the man’s locked up, and back earlier again, in terms of a scene, and we hear of the crime. And then time shoots forward to a new scene, where this younger son is at a sports game, a basketball game. And then the father’s watching the son at the sports game. And then the next scene goes back in time, where the poet himself is a boy now, and at a sports game where his own father never made it. And then time changes again to a new scene, to a more recent time where the poet’s older son has heard of the father’s crimes from a stranger. And then we’re right back in the present moment, and the sleepless son is telling his dad, it’s OK, daddy. And then that son is crawling into his dad’s arms, wanting to find the sleep that he’s been fighting. And then we go back to a bunch of men coming home from a bar, with stories that aren’t easy to tell. And so time goes back and forth and back and forth, in all of these scenes that we can see so clearly.

And the poet isn’t telling us too much about all the things that he’s thinking, except, in the simplicity and purity of the language, we feel all the weight of the things that he is thinking. He’s not saying, “And this was in my mind, and that was in my mind, and this was in my mind, and these four things were in my mind, and I was angry at the stranger, and I didn’t want a stranger to tell this other son,” but we know it there, because he’s giving us such simple images to see. And they are quickly described, but we never feel rushed, while seeing those scenes. And as a result, I think we’re brought into a phenomenal and beautiful, elongated moment that holds so much time in it.

[music: “Memoriam” by Gautam Srikishan]

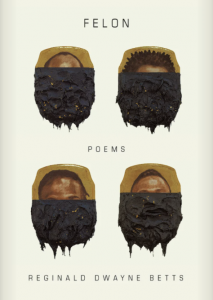

Reginald Dwayne Betts is a master at using words with multiple meanings. The book that this poem is in is called Felon. And that word, “felon,” comes from an old word, “felun,” an adjective meaning cruel or wicked. And so by putting that on the front cover of the book, there’s a challenge. And even the front cover of the book has the paintings of four Black men whose faces are mostly covered over with cloth or with paint, and so all you see is the color of their skin and the word “felon.” And this book is in a certain sense an exploration of all these kinds of terms that are used in criminal contexts — used in the justice system or in prison — and not just the word “felon,” but other words, too. So “reentry,” for instance: reentry is a way to talk about what happens when a person has served a sentence in prison and is now coming home; but also “essay”: “essay” coming from the French word “essayer,” meaning to try. And you wonder, is this over and over again trying to reenter? And that reentry isn’t just when a person has served a sentence and is now home, but actually, you’re going to be trying over and over again to reenter.

[music: “What Did You Not Hear” by Gautam Srikishan]

Reginald Dwayne Betts served an eight-year prison sentence for robbery, as he was mentioning in the poem, fourteen months of which was in solitary confinement. And when he was in solitary, somebody, and he never knew who, would put arbitrary books through his door, which he was reading, including, at one point, the 1971 poetry anthology The Black Poets. And he describes this as a way that moved him into poetry. And so when he left, he went on to the University of Maryland, and then he went on to study law, and he got accepted at the bar. And now he’s doing, or has recently completed, a PhD in law at Yale.

And so, for him, he is highlighting through this use of language a phenomenal critique of the ways within which words, slang words that are used to refer to what it’s like to serve a prison sentence, continue on outside. And he is using this character of time, I think, to critique the idea that criminal justice is served and finished in time and that the question about reentry, the burden about what reentry is, is put on people who — more than likely, in many situations — shouldn’t have been serving the amount of time that they were: eight years for a carjacking, fourteen months in solitary confinement. He was sixteen, and he was tried as an adult. So that criminal justice system is being put under the spotlight, and that, I think, is being held up to be examined in this whole book, and elements of that in this poem, as well.

[music: “What Did You Not Hear” by Gautam Srikishan]

There are all kinds of reachings-out that are happening in this poem. A man is reaching out to his friends by going out to spend an evening talking and drinking at a bar. And a man is reaching out to the son that’s awake in the middle of the night, and lamenting the lack of reaching out that happened between him and his dad when he was younger, going to sports games himself. And so in many ways, this is a poem exploring its own masculinities and exploring the connection of tenderness and the vulnerability of sadness that’s there. There is pain, in terms of how he worries about running towards failure, and pain too in the way that some stranger told his older son the story about his father’s spell in prison, and wanting to not let that happen a second time, with the second son, but presumably also knowing that that’s going to be a burden — a sentence, really — that the younger son will carry.

I find it so moving, the way that just after he’s told his younger son, the scene flips and moves forward and says, “This, months / before he would drop bucket after bucket / on opposing players, the entire bedraggled / bunch five & six & he leaping as if / every lay-up erases something.” He sees this energy in his younger son, a few months later, after this scene, and he is wondering, is my son doing this to erase something, or hoping that something could be erased? What? The shame that’s being put on the family because of something that was paid for in the justice system already? There is a sense of vulnerability and wishing that there could be such a thing as redemption, in a system that doesn’t seem to believe in redemption for people.

[music: “White Filament” by Blue Dot Sessions]

I think this poem has a variety of invitations. One of them is to reflect on how a criminal justice system punishes families and punishes people, far beyond a particular custodial sentence. Whether or not that custodial sentence was even just in the first place, of course, is being critiqued, and even if it is, to consider the ongoing impact on the entirety of the family, the callous way within which people might speak about somebody else and what’s the first story we tell about them. I think that’s being highlighted here, and the way within which language to speak about the experience of a family being caught up in the criminal justice system needs to be considered, and we need to have a family-first and person-first approach toward thinking about what true redemption, in terms of thinking about what a societal justice could look like.

[music: “White Filament” by Blue Dot Sessions]

“Essay on Reentry” by Reginald Dwayne Betts:

“At two a.m., without enough spirits

spilling into my liver to know

to keep my mouth shut, my youngest

learned of years I spent inside a box: a spell,

a kind of incantation I was under; not whisky,

but History: I robbed a man. This, months

before he would drop bucket after bucket

on opposing players, the entire bedraggled

bunch five & six & he leaping as if

every lay-up erases something. That’s how

I saw it, my screaming-coaching-sweating

presence recompense for the pen. My father

has never seen me play ball is part of this.

My oldest knew, told of my crimes by

a stranger. Tell me we aren’t running

towards failure is what I want to ask my sons,

but it is two in the a.m. The oldest has gone off

to dream in the comfort of his room, the youngest

despite him seeming more lucid than me,

just reflects cartoons back from his eyes.

So when he tells me, Daddy it’s okay, I know

what’s happening is some straggling angel,

lost from his pack finding a way to fulfill his

duty, lending words to this kid who crawls

into my arms, wanting, more than stories

of my prison, the sleep that he fought while

I held court at a bar with men who knew

that when the drinking was done,

the drinking wouldn’t make the stories

we brought home any easier to tell.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Lily Percy: “Essay on Reentry” comes from Reginald Dwayne Betts’s Felon. Thank you to W. W. Norton & Company for giving us permission to use Reginald’s poem. Read it on our website, at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Chris Heagle, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, and me, Lily Percy.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions. This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land.

We also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me. Find those wherever you like to listen, or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.