Richard Blanco

Looking for The Gulf Motel

Is something lost once it’s gone? How do we blend sadness with sweet memory?

We’re pleased to offer Richard Blanco’s poem, and invite you to sign up here for the latest from Poetry Unbound.

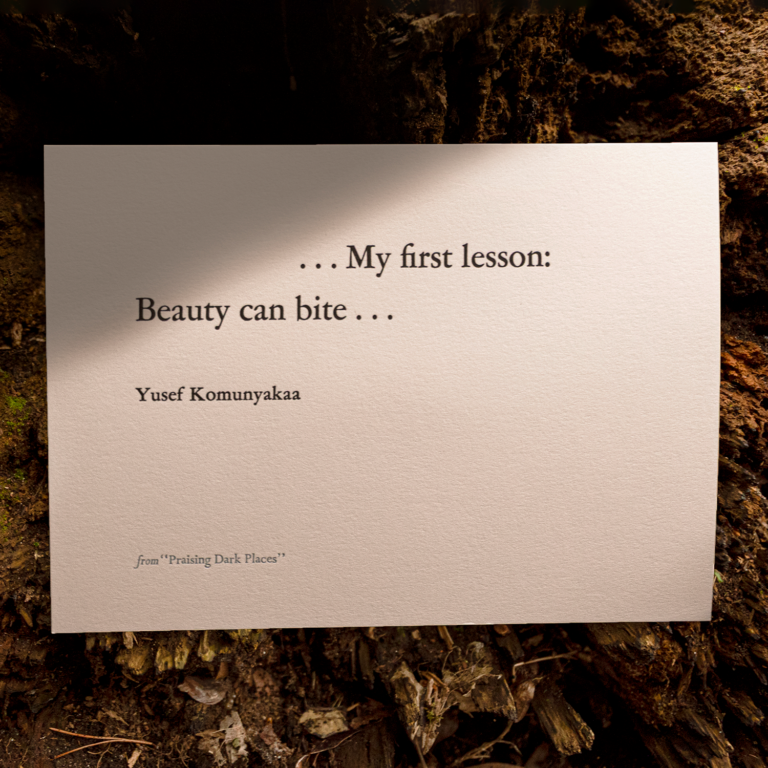

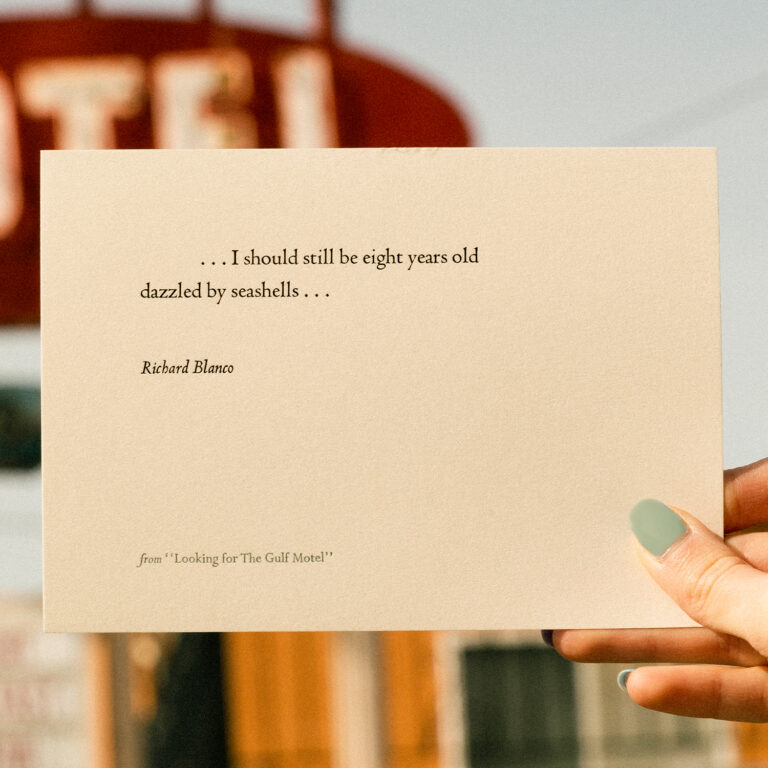

Letterpress print by Myrna Keliher. Photography by Lucero Torres. © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Richard Blanco practiced civil engineering for more than 20 years. He is now an associate professor of creative writing at his alma mater, Florida International University. His books of nonfiction and poetry include Looking for the Gulf Motel and, most recently, How to Love a Country.

Transcript

Transcription by Heather Wang.

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and every time I go to visit my parents, I always walk down the corridor to have a look into the room that was mine when I was growing up. The room’s changed now, you know. It’s got bunkbeds in it, because of grandkids coming to stay, and everything’s changed, really. But somehow, looking into that room, I’m also looking into a part of me. A poem is made up of stanzas, often, and “stanza” is the Italian word for “room.” So in a certain sense, by looking into that room I’m looking into a stanza of who I was — not anymore, but somehow that stanza still echoes with who I am today.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Looking for The Gulf Motel” by Richard Blanco:

“Marco Island, Florida

“There should be nothing here I don’t remember . . .

“The Gulf Motel with mermaid lampposts

and ship’s wheel in the lobby should still be

rising out of the sand like a cake decoration.

My brother and I should still be pretending

we don’t know our parents, embarrassing us

as they roll the luggage cart past the front desk

loaded with our scruffy suitcases, two-dozen

loaves of Cuban bread, brown bags bulging

with enough mangos to last the entire week,

our espresso pot, the pressure cooker–and

a pork roast reeking garlic through the lobby.

All because we can’t afford to eat out, not even

on vacation, only two hours from our home

in Miami, but far enough away to be thrilled

by whiter sands on the west coast of Florida,

where I should still be for the first time watching

the sun set instead of rise over the ocean.

“There should be nothing here I don’t remember . . .

“My mother should still be in the kitchenette

of The Gulf Motel, her daisy sandals from Kmart

squeaking across the linoleum, still gorgeous

in her teal swimsuit and amber earrings

stirring a pot of arroz-con-pollo, adding sprinkles

of onion powder and dollops of tomato sauce.

My father should still be in a terrycloth jacket

smoking, clinking a glass of amber whiskey

in the sunset at the Gulf Motel, watching us

dive into the pool, two boys he’ll never see

grow into men who will be proud of him.

“There should be nothing here I don’t remember . . .

“My brother and I should still be playing Parcheesi,

my father should still be alive, slow dancing

with my mother on the sliding-glass balcony

of The Gulf Motel. No music, only the waves

keeping time, a song only their minds hear

ten-thousand nights back to their life in Cuba.

My mother’s face should still be resting against

his bare chest like the moon resting on the sea,

the stars should still be turning around them.

“There should be nothing here I don’t remember . . .

“My brother should still be thirteen, sneaking

rum in the bathroom, sculpting naked women

from sand. I should still be eight years old

dazzled by seashells and how many seconds

I hold my breath underwater–but I’m not.

I am thirty-eight, driving up Collier Boulevard,

looking for The Gulf Motel, for everything

that should still be, but isn’t. I want to blame

the condos, their shadows for ruining the beach

and my past, I want to chase the snowbirds away

with their tacky mansions and yachts, I want

to turn the golf courses back into mangroves,

I want to find The Gulf Motel exactly as it was

and pretend for a moment, nothing lost is lost.”

[music: “Family Tree” by Gautam Srikishan]

This is a beautiful poem that I love, and I’ve loved since the first moment I read it. And it’s doing at least three things at once. The first thing it’s doing is telling the story of a family: an 8-year-old boy, a 13-year-old brother, and their parents, going on a holiday to The Gulf Motel, which is two hours from their Miami home. And the second thing the poem is doing is it’s telling us that time has passed, because toward the end we hear the voice of the poet coming in, saying he’s not eight anymore, he’s 38. And so much has changed. The motel’s gone, but he’s looking for it. And other things have gone, too: childhood, nostalgia, and his father. That father never saw the boys grow into men who’d be proud of him.

And the third thing the poem is doing is it’s enacting an action of remembering. What happens when we remember? Why do we remember? Is it sweet or sad? Is it both? If you particularly associate warm memories, romantic memories, nostalgic memories with a place, and then that place is changed, does that mean that all those memories are gone? This is a poem that’s almost sad in remembering everything that’s gone. But what’s so beautiful about the poem is that in remembering, Richard Blanco brings in the sounds and the scents and the music and the sights, from garlic to watching his parents dance on the balcony. They are there again. Even though the poet is feeling sad about everything that’s gone, I’m always deeply moved by the memory about what was and the way within which the poem brings that to the now.

[music: “Family Tree” by Gautam Srikishan]

One of the many brilliances of Richard Blanco as a poet is his capacity to sketch characters. And in this poem you see it perfectly. There’s the boys: one’s so young, and one’s in early puberty. There’s the family, who are going on holiday and knowing that they couldn’t eat out, so there’s those suitcases stuffed with bread and a pork roast and a coffee machine and the slow cooker. There’s the thrill of the point of view of an eight-year-old seeing the sun go down over the water, rather than coming up over the water. And then there’s the memory he has of his mother — the detail of the daisy sandals and the teal swimsuit and the amber earrings; and then the dad’s jacket and whisky, and the fact that he would sit and watch the boys dive into the pool. And then the boys would sit and watch their parents dancing on the balcony with no music, just to the sound of the waves.

There is such a depiction of family, here, as well as privacies — the brother, curious about sex, and sneaking rum into the bathroom; the younger boy still much more innocent. This family dynamic is going to change. But he brings us into warmth and kindness, a deep loveliness of this family unit for this period of time — not perfection; he seems to be very aware and also embarrassed by the scruffy suitcases. But in the midst of that, that comparison of “we don’t have as much money as other people,” there is a deep sense of seeing the members of his family and holding them in a gaze of love.

[music: “Family Tree” by Gautam Srikishan]

There’s a chorus line throughout this poem. It’s the first line of the poem: “There should be nothing here I don’t remember…” And then it’s repeated a few times through the poem. It’s a strong statement, “There should be nothing here I don’t remember,” which is another way of saying: everything should be exactly as I left it — which is a desire to reconnect with the past, a desire to come in contact with the way things were.

Even if The Gulf Motel had been there, things would’ve changed anyway. Presumably, the carpets would’ve changed, or, of course, the people would’ve changed, or buildings around the motel would’ve changed. So the idea that we need the past to stay exactly as the past, the locations of the past to be unmodified, in order for us to remember, is a thing that this poem is playing with.

In those repeated “There should be nothing here I don’t remember…,” it isn’t just that Richard Blanco is trying to remember back to a past because it was a lovely memory. There is a prediction: something’s going to happen. And the something that’s happened isn’t the fact that The Gulf Motel is gone. It is the fact that the dad has died. The poem doesn’t tell us when, but certainly it tells us twice that he’s not there anymore, that he has died, that no more will these boys be able to look back at him with love and pride in the way that he looked at them with love and pride.

And this poem, therefore, is a lament for him and a lament for places where they had shared memories that are gone. And in the midst of being a lament for a father who’s died and the fact that the places of warm memories have gone, too, it is a reenactment of the act of remembering, because The Gulf Motel is built again in this poem. And I see the father looking at his children and his children looking back at him, in this poem. The poem does the remembering. The poem is a house of memory into which you can go.

[music: “Family Tree” by Gautam Srikishan]

So this poem is from Richard Blanco’s first book, a book also named after the same poem, Looking for The Gulf Motel. And I got the book a good few years ago and read through it and loved it. I brought it with me on a work trip, where me and my colleague, who was also a close friend, were away for a few nights, and the first night, I had to go out to a meeting. And as I was leaving, I tossed my friend the book and said: I think you’ll love this book. And when I came back from the meeting, after about an hour, my friend was sitting exactly where he’d been when I left, and his face was completely covered in tears. And he said to me: I have been reading this first poem, “Looking for The Gulf Motel,” over and over and over for the last hour. And then he said: I think I know it off by heart now. And that friend is dead now. He died in the first year of COVID. And this poem — a poem about remembering the past and a poem about knowing that there is death and there is loss and that somehow, still, remembering can be a sweet beauty, even if it’s a sweet kind of pain — this poem from Richard Blanco has become a poem of mine now, too, because it is a private memory that I share with that friend.

And that’s one of the things that a poem is yearning to do. I think a poem is always curious to know, where will it land in the audience? Where will it land in the readers? How will this poem acquire a new life in people who aren’t going to remember The Gulf Motel, but who will remember the experience of loving this poem, the experience of sharing this poem? And this way a poem, too, is a dance between the writer, between the art of poetry, and then the people who read the poem. And we’re brought into all kinds of ways within which language, within which music, within which re-membering can bring us to hold something that we thought was lost, but can possibly be remembered in a different way.

[music: “Family Tree” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Looking for The Gulf Motel” by Richard Blanco:

“Marco Island, Florida

“There should be nothing here I don’t remember . . .

“The Gulf Motel with mermaid lampposts

and ship’s wheel in the lobby should still be

rising out of the sand like a cake decoration.

My brother and I should still be pretending

we don’t know our parents, embarrassing us

as they roll the luggage cart past the front desk

loaded with our scruffy suitcases, two-dozen

loaves of Cuban bread, brown bags bulging

with enough mangos to last the entire week,

our espresso pot, the pressure cooker–and

a pork roast reeking garlic through the lobby.

All because we can’t afford to eat out, not even

on vacation, only two hours from our home

in Miami, but far enough away to be thrilled

by whiter sands on the west coast of Florida,

where I should still be for the first time watching

the sun set instead of rise over the ocean.

“There should be nothing here I don’t remember . . .

“My mother should still be in the kitchenette

of The Gulf Motel, her daisy sandals from Kmart

squeaking across the linoleum, still gorgeous

in her teal swimsuit and amber earrings

stirring a pot of arroz-con-pollo, adding sprinkles

of onion powder and dollops of tomato sauce.

My father should still be in a terrycloth jacket

smoking, clinking a glass of amber whiskey

in the sunset at the Gulf Motel, watching us

dive into the pool, two boys he’ll never see

grow into men who will be proud of him.

“There should be nothing here I don’t remember . . .

“My brother and I should still be playing Parcheesi,

my father should still be alive, slow dancing

with my mother on the sliding-glass balcony

of The Gulf Motel. No music, only the waves

keeping time, a song only their minds hear

ten-thousand nights back to their life in Cuba.

My mother’s face should still be resting against

his bare chest like the moon resting on the sea,

the stars should still be turning around them.

“There should be nothing here I don’t remember . . .

“My brother should still be thirteen, sneaking

rum in the bathroom, sculpting naked women

from sand. I should still be eight years old

dazzled by seashells and how many seconds

I hold my breath underwater–but I’m not.

I am thirty-eight, driving up Collier Boulevard,

looking for The Gulf Motel, for everything

that should still be, but isn’t. I want to blame

the condos, their shadows for ruining the beach

and my past, I want to chase the snowbirds away

with their tacky mansions and yachts, I want

to turn the golf courses back into mangroves,

I want to find The Gulf Motel exactly as it was

and pretend for a moment, nothing lost is lost.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Chris Heagle: “Looking for The Gulf Motel” comes from Richard Blanco’s book of the same name. Thank you to University of Pittsburgh Press for giving us permission to use Richard’s poem. Read it on our website, at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, and me, Chris Heagle.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions.

This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. You may enjoy our other podcasts: On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me. Find those wherever you’d like to listen, or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.