Rita Dove

Eurydice, Turning

How do you speak with your mother when she’s forgotten who you are? By turning to myth, it seems, and by holding gentleness with bewilderment, love with patience. Rita Dove lets us overhear a phone call, and in this listening, we hear lifetimes unfold.

We’re pleased to offer Rita Dove’s poem, and invite you to sign up here for the latest from Poetry Unbound.

Letterpress print by Myrna Keliher. Photography by Lucero Torres. © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Rita Dove was U.S. Poet Laureate from 1993–1995 and she served as the Poet Laureate of Virginia from 2004–2006. In 1987 she received the Pulitzer Prize in poetry for her book Thomas and Beulah. She is currently Commonwealth Professor of English at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville.

Transcript

Transcript by Heather Wang

Pádraig Ó Tuama: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and one of the reasons I love poetry and old mythologies is that they help me to navigate change. Life is so full of changes, you know — friendships come or go, or relationships end, or someone dies, or someone becomes so ill or immobilized that the relationship needs to change. Change is the only constant. And often, change can make you feel isolated. Reading poems that speak about the experience of change and reading old mythologies where you hear an echo of yourself can give you an accompaniment to the change, to say, you’re not alone.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Eurydice, Turning” by Rita Dove:

“Each evening I call home and my brother answers.

Each evening my rote patter, his unfailing cheer—

until he swivels; leans in, louder:

“‘It’s your daughter, Mom! Want to say

hello to Rita?’ My surprise each time

that he still asks, believes in asking.

“‘Hello, Rita.’ A good day, then;

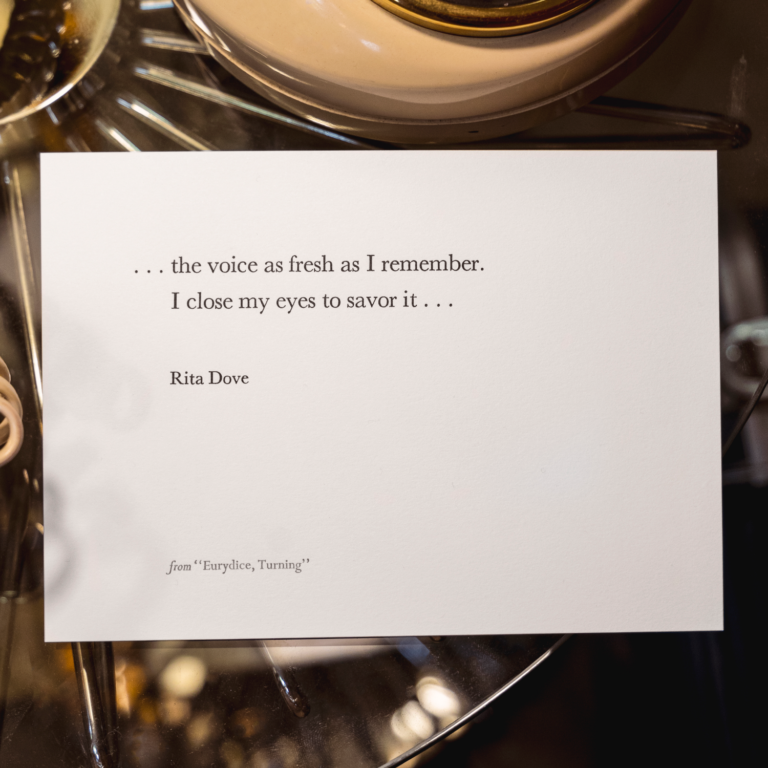

the voice as fresh as I remember.

I close my eyes to savor it

“but don’t need the dark to see her

younger than my daughter now,

wasp-waisted in her home-sewn coral satin

“with all of Bebop yet to boogie through.

No wonder Orpheus, when he heard

the voice he’d played his lyre for

“in the only season of his life that mattered,

could not believe she was anything

but who she’d always been to him, for him. …

“Silence, open air. I know what’s coming,

wait for my brother’s ‘OK, now say

goodbye, Mom’— and her parroted reply:

“‘Goodbye, Mom.’

That lucid, ghastly singing.

I put myself back into a trance

“and keep talking: weather, gossip, news.”

[music: “First Grief, First Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

I love this poem. I think it’s so beautiful. I was so struck by the pathos in it. I thought of so many people that I know, who are living around and with someone whose memory is fading. And that could be a parent or a spouse or a partner or a neighbor or a friend; it could be yourself. And this poem connects with powerful insight about the sadness, about the almost teasing way where a person’s voice sounds like themself and still is themself, but it is a changed self, and that people can be in different times at the same time, and that there is all kinds of ways of lament and sadness and adjustment that’s needed for that.

In the last part of the poem, Rita Dove says, “I put myself back into a trance.” And then she continues to talk, about “weather, gossip, news.” She has to almost adjust her sense of presence to herself, before she can move from talking to the mother who is her mother, but who nonetheless seems to be present in a different time, and then modifying that to go back to talk to her brother.

[music: “First Grief, First Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

The narrative of the poem is that Rita Dove is phoning her brother, and the brother seems to be the primary carer for their mother. And she phones him every evening: “Each evening I call home and my brother answers. / Each evening my rote patter, his unfailing cheer.” He sounds like such a nice guy.

And then he passes the phone over to the mother, and on a good day, she’ll say, “Hello, Rita.” And it’s amazing the way there’s coding in this poem, even just in two words: “Hello, Rita.” And then the poem says: “A good day, then; / the voice as fresh as I remember.” And a good day seems to bring with it the kind of pain that comes with a good day, because with a recognition like that, simple words — “Hello, Rita,” which her mother must have said so many times throughout their life — there comes with that all of this longing to be her daughter again.

And those roles seem to be reversed, and her mother is now back in a time when she’s younger than Rita Dove’s daughter now. And Rita Dove is saying that she was “wasp-waisted in her home-sewn coral satin // with all of Bebop yet to boogie through.” She paints a picture of a magnificent person, who sews, who dances, who loves music — so much vivacity, so much life ahead of her. And yet there’s lament in that, because there isn’t a conversation that’s going to happen between Rita Dove and her mother.

The brother says 10 words at the start: “It’s your daughter, Mom! Want to say / hello to Rita?” And in those 10 words — they sound so simple, so easy, but there is so much information, because he’s reminding the mother that she has a daughter. And he’s reminding her that she is a mother. And he’s reminding her of her daughter’s name, Rita. And he’s asking her if she wants to say hello — nothing too much, not “have a conversation,” not “say how you are,” not “say what’s going on” — just “say / hello,” nice and easy. And in that is profound skill and understanding, and deeper than both of those is the most extraordinary form of love.

[music: “Bivly” by Blue Dot Sessions]

The poem’s title is “Eurydice, Turning,” and there’s a reference to Orpheus in the middle of the poem, too. And the story of Orpheus and Eurydice is from Greek mythology. They were lovers, and they were really the lovers of each other’s lives. And Eurydice was killed early in their relationship, and taken down to Hades, the place of the dead, the underworld.

And Orpheus goes on this epic journey to Hades to bring her back, and he woos the population of the underworld, including Hades and Persephone, the queen of destruction — he woos them with his singing and pleads that he can take Eurydice back to the overworld. And because his music was so lovely, they said yeah, under one condition: that he walks ahead, she walks behind, and that he never turns around at any point while they’re leaving Hades; and that if he does, she’ll be taken back to Hades forever. So they make the whole way to the gates of Hell, and he’s outside, he’s in the light, and he turns around to look, but she is still not quite out. She’s half in, half out. And she’s taken back down.

This beautiful, terrible story unfolds in a way that Orpheus never really recovers from the loss. He is permanently attached to the presence of the absence of his deepest beloved. You see that Rita Dove refers to this as “the only season of his life that mattered,” because in all the stories that occur of him in the rest of mythology, he still is this character who’s plagued by loss and who loss is sitting in, very, very deeply. And he wants to believe that Eurydice, his beloved, would be to him now who she’d always been to him. And in a certain, brutal sense it’s a story about what it means to let go, what it means to admit change, what it means to allow grief to do its own work in you.

And Rita Dove is using this beautiful story with a sharp point to speak back to herself, because especially when she hears the echo of her mother’s beautiful music, perhaps she wants to charm her mother back into her own self — to bring about a conversation about the coral satin skirt or bebop or dancing or all of the fashions of the day, the stories of their life, the politics of their life, the ways within which her mother sounds like such a person of love and vivacity in this poem. But she is saying that she has to learn the message that Orpheus was never able to learn, which is to let the beloved go to the place where they’ve turned to, even though it causes great sadness for the ones who witness it.

[music: “Ice Tumbler” by Blue Dot Sessions]

I always wonder about time in a poem. And in this poem, I wonder how long it took to get to the stage where Rita Dove would know that when her mother says, “Hello, Rita,” that that’s a good day, and then to know how to notice her own sadness that that good day isn’t going to turn into a conversation, like the old days, and to be present to the sadness, but to not project that anxiety onto the mother — Come on, remember! Remember this? Ask me something else — and also not to project that sadness as anxiety, or hostility to the brother.

So many times, when we are filled with the pathos, the living lament that can happen when you are around somebody who is in slow decline, it can be really easy to externalize the conflict you feel in yourself with someone else: to start a fight with a nurse, to start a fight with a spouse, a sibling, a surviving parent. One of the profound intelligences of this poem is how little conflict there is between Rita Dove and her brother. And how do they learn that kind of equanimity with each other? It is a stressful thing, and a sad thing, to love somebody whose life is changing so profoundly and where care means so many different things happening.

And that, I think, is the invitation of the poem: to think, Look at what might be possible. It might be that you can be more loving to each other. And that anxiety and lament and living grief can cause all kinds of fractures between yourself and other people, and between yourself and yourself. This, I think, is one of the intelligences of this poem, which is to find a way to allow yourself to change and, perhaps, to look for the stories that will support that. There’s no indication of “rush yourself through grief” or “rush yourself through sadness,” in this poem. There’s no insinuation that people need to find a way to speed through the stages of their own grief. But there is a recognition that it is possible to be more loving to each other, while we live through the phases of grief that affect your life so much.

[music: “Ice Tumbler” by Blue Dot Sessions]

“Eurydice, Turning” by Rita Dove:

“Each evening I call home and my brother answers.

Each evening my rote patter, his unfailing cheer—

until he swivels; leans in, louder:

“‘It’s your daughter, Mom! Want to say

hello to Rita?’ My surprise each time

that he still asks, believes in asking.

“‘Hello, Rita.’ A good day, then;

the voice as fresh as I remember.

I close my eyes to savor it

“but don’t need the dark to see her

younger than my daughter now,

wasp-waisted in her home-sewn coral satin

“with all of Bebop yet to boogie through.

No wonder Orpheus, when he heard

the voice he’d played his lyre for

“in the only season of his life that mattered,

could not believe she was anything

but who she’d always been to him, for him. …

“Silence, open air. I know what’s coming,

wait for my brother’s ‘OK, now say

goodbye, Mom’— and her parroted reply:

“‘Goodbye, Mom.’

That lucid, ghastly singing.

I put myself back into a trance

“and keep talking: weather, gossip, news.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

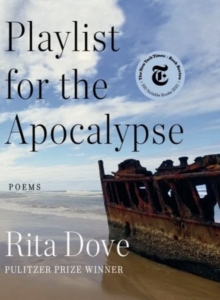

Chris Heagle: “Eurydice, Turning” comes from Rita Dove’s book Playlist for the Apocalypse. Thank you to W. W. Norton & Company, who gave us permission to use Rita’s poem. Read it on our website, at onbeing.org.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Poetry Unbound is: Gautam Srikishan, Erin Colasacco, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Lucas Johnson, and me, Chris Heagle.

Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions.

This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. You may enjoy our other podcasts: On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me. Find those wherever you’d like to listen, or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.