Robert Franklin and Margaret Poloma

Pentecostalism in America

Pentecostalism began on the American frontier, and it has become one of the largest expressions of global Christianity. In less than a century, it has grown to hundreds of millions of adherents. Today, Pentecostalism is pan-denominational. There are charismatic Catholics and Lutherans, unaffiliated Pentecostal communities, and established Pentecostal traditions, most prominently the Assemblies of God.

Krista Tippett speaks with a theologian about the rise of Pentecostal worship among African-Americans in every denomination and a sociologist on her study of modern day Pentecostals — whom she sees as mystics among us.

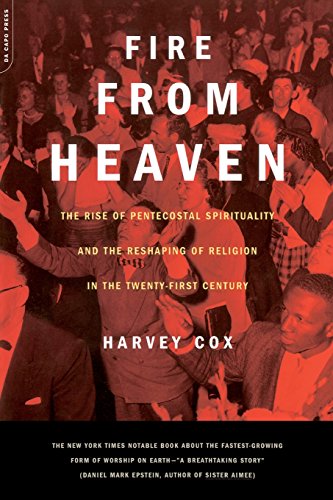

Image by Robert Nickelsberg/Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

Guests

Robert Franklin is Presidential Distinguished Professor of Social Ethics at the Candler School of Theology at Emory University, and a senior fellow at the Center for the Interdisciplinary Study of Religion at Emory University.

Margaret Poloma is the author of Main Street Mystics: The Toronto Blessing & Reviving Pentecostalismand Professor Emeritus at the University of Akron.

Transcript

June 10, 2004

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: This is Speaking of Faith, conversation about belief, meaning, ethics and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. This hour, “Pentecostalism in America Today.” Pentecostalism is the largest and most influential religious movement ever to originate in the United States. In less than a century, it has grown to hundreds of millions of adherents. The New York Times reports that 25 percent of Christians worldwide are Pentecostal. The word `Pentecost’ is taken from an ancient Jewish observance. The New Testament says that it was on Pentecost that the Holy Spirit descended on the early Christians for the first time. The first modern Pentecostal was a women, Agnes Ozman. She spoke in tongues on the first day of the 20th century at the original Pentecostal community in Topeka, Kansas. Then in 1906, an African-American preacher, William Joseph Seymour, led what became known as the Azusa Street Revival in downtown Los Angeles. This unprecedented gathering of people from every class and race lasted for three years. From there, Pentecostalism began to spread across the world. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Pentecostal charismatic movement washed across denominational lines and barriers. Widely reported occasions of speaking in tongues and spiritual healing spread from an Episcopal church in California through Ivy League campuses and into the global Roman Catholic Church as well as every major Protestant denomination. Today, Pentecostalism is pan-denominational. There are charismatic Catholics and Lutherans. There are unaffiliated Pentecostal communities, and there are established Pentecostal traditions, most prominently the Assemblies of God.

In this hour, we’ll explore the power of Pentecostalism. From the outside, what the believers call the presence of the Spirit can look like religious hype or hysteria. But sociologist Margaret Poloma calls it modern-day mysticism at odds with much of contemporary culture. We’ll speak with her later. But first, Robert Franklin, a professor of social ethics at Emory University. He’ll take us inside Pentecostalism’s rapid expansion in the mainstream life of African-Americans. He is a lifelong member of the Church of God in Christ. This church emerged in the immediate wake of the Azusa Street Revival, formed and led by African-Americans one generation removed from slavery.

ROBERT FRANKLIN: As a child, I grew up around what the former dean of Harvard Divinity School and my friend Krister Stendahl used to refer to Pentecostalism as high-voltage religion, ’cause, I mean, he had this keen interest in the vitality that Pentecostalism represented for traditions at the Harvard Divinity School when I was a student there, and that just bowled me over that he would take note. I mean, here’s this Lutheran…

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. FRANKLIN: …who later became a bishop. It was just a wonderful incongruence. And I was just saying that part of the joy of being a child in that kind of congregation was, I mean, you just had a sense there’s always a lot of energy and a lot of singing and hand clapping and foot stomping and backslapping and hugging and kissing and high-fives, a lot of touching. It was a very tactile faith. There’s a tiny kitchen in the congregation where they’re preparing meals, so it just felt like home, and we stayed there all day. When we arrived for Sunday morning, you know, Sunday School, we didn’t go home until, gosh, 3:00 in the afternoon, so Sunday was sort of spent in that space. And that was a place where my own theological education began, and my own fundamental lens through which I view the larger world was formed.

MS. TIPPETT: I believe that there’s a lot of confusion in terms like `fundamentalism,’ `Pentecostalism,’ `evangelicals.’ And of course, that word `fundamentalism’ has become very important in our public vocabulary in the last couple of years. When you think of your Pentecostal upbringing, do you identify it as fundamentalist?

DR. FRANKLIN: I do not. It’s interesting that even though the clergy in the Pentecostal churches that I knew and listened to — they, in their own untutored ways, distinguished between the way in which they construed the Christian message from counterparts that back then we’d hear on the radio, particularly, you know, kind of white fundamentalist preachers who had a very, what struck us as a kind of narrow and somewhat rigid approach to Scripture. And there were these very specific fundamentals of the faith that, you know, people had to buy into, or they weren’t in the fold. And Pentecostalism shared a lot of that spiritual terrain with the fundamentalists, but it also diverged in significant ways. And one of them was the way in which the Spirit interacts with the printed word with words. So Spirit and word live in a kind of, if I can use this fancy term, dialectical tension. And the Spirit is still revealing new truth to the church, to the congregation, giving us new wisdom and insight about how to respond to social evil like racism and sexism and the neglect of children and so on. So we felt, gee, we had kind of an advantage by paying attention to the living voice of the Spirit rather than simply focusing in some narrow sense on the fundamentals of the faith and the focus on the word to the exclusion of other ways in which God might reveal God’s self to us.

MS. TIPPETT: I also know about Pentecostalism that, you know, whereas a lot of liberal traditions in this country now are very proud of themselves for having ordained women for a couple of decades, that Pentecostal — some Pentecostal churches were ordaining women a hundred years ago.

DR. FRANKLIN: Yes. Yes. Absolutely.

MS. TIPPETT: Was that true in the church you grew up in?

DR. FRANKLIN: It was not in my church. My church is slowly making progress, and I do think it is in the process of change. There is a commission in the Church of God in Christ, which is the largest African-American Pentecostal tradition in the United States — some reckon between 3.5 and five million members — they’re a commission examining this precise question in relation to Scripture. And here again, this is where the Spirit kind of keeps us a little off balance, because if we were fundamentalists, we could just say, gee, we point to these Scriptures and these texts and say, `No, look, you know, women are not included in ordained ministry. That’s the end of the debate.’ But if you’re kind of open to new revelation, to ongoing revelation, you got to say, `Well, wait a minute. There are some Scriptures here that suggest that, you know, just to cite one, `In the last day, I will pour out my Spirit on all flesh. His sons and daughters shall prophesy.’ I was always fond of listening on women’s days in the black church. The women would cite that Scripture. They would preach messages and just gently remind the male clergy that God uses women and men. So — but you’re right. I mean, a hundred years ago, the United Holy Church of America — wonderful title, United Holy Church of America — based in North Carolina was ordaining women. There were female bishops in that tiny congregation. And yet from its fertile ground sprung one of the nation’s premier preachers, Dr. James Forbes, who currently serves as the senior pastor of the historic Riverside Church in New York City. You know, who knew in this — storefront churches in North Carolina would emerge, I mean, this really incredible preacher and public theologian? And I think that’s a part of a slice of a Pentecostal tradition that is often overlooked.

MS. TIPPETT: Emory University theologian Robert Franklin.

In recent years, some 35 to 40 percent of mainline African-American churches in this country across denominations have embraced what are called neo-Pentecostal forms of worship. Some criticize this development as a triumph of entertaining worship style over theological substance. They see in it a decline of the social-justice, civil-rights oriented black church.

DR. FRANKLIN: There is an expression of Pentecostalism that is exceedingly escapist and almost narcissistic in its focus on religious experience…

MS. TIPPETT: And that would maybe be the image…

DR. FRANKLIN:…and speaking in tongues and so on.

MS. TIPPETT: …right, of people speaking in tongues.

DR. FRANKLIN: Right, sure.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

DR. FRANKLIN: Sure. And to be sure, that is there. But I’m suggesting that that, itself, represents a slight distortion of the way in which I understand the phenomena of the Spirit’s gift and arrival into the church and moving the church out into the world for service and loving the world as God loves the world, and serving the world. And there’s this constant sort of rhythmic dynamism between individual renewal and empowerment and making an impact on justice in the world.

MS. TIPPETT: So some people say about neo-Pentecostalism in African-American churches that it’s really all about individual experience and that it’s about the worship services being lively and engaging, right?

DR. FRANKLIN: Yeah. Yeah. No, I think that really is missing the — what’s under the tip of the iceberg.

MS. TIPPETT: OK. OK.

DR. FRANKLIN: That’s the most visible sign is that now, you know, the voltage of worship services has been turned up in traditional Baptist and African Methodist, Episcopal and other traditional African-American Christian sort of mainline traditions. Suddenly this new fervor and energy appear, and they are manifest immediately through styles of worship.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

DR. FRANKLIN: But there is a deeper, and it is more theological in nature, a deeper impact that has to do with mining the resources of the Christian tradition to mobilize and empower people to have courage in the public square. And I think one of my concerns, and a number of people from Cornel West to Parker Palmer to all sorts of folks have said this, that one of the tragedies of the civil rights movement and the civil rights activist clergy was that after the fervor of the ’60s, Dr. King’s assassination, many of them failed to engage in what Palmer refers to as rituals of personal renewal. Many of them burned out during the ’70s.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

DR. FRANKLIN: And there was nothing to kind of recharge and send them back into service. And so that’s what I think that neo-Pentecostalism represents. And I think the fact that it’s catching on in the kind of traditional, you know, more mainstream, laid — rather, staid bourgeois congregations is really quite phenomenal. I mean, these are congregations that I know firsthand 20 years ago would have banished the thought, banished the practice — `You don’t stand up and sing aloud’ or `You cannot shed tears in a worship service. What is going on here?’ — and would actively discourage those expressions of more exp — emotionally expressive faith to now encouraging and permitting and finding that as people experience a kind of therapeutic transformation in that moment, they are then more open to being sent into the local housing projects of Philadelphia or Brooklyn to spend the rest of the afternoon mentoring kids or delivering meals or talking to young women about abstaining and avoiding pregnancy and so on — things that, you know, these men and women would not have considered earlier. Neo-Pentecostalism has ushered in some new conviction about what the radical love ethic of Jesus calls us to. And I can’t attribute that to anything other than the presence of this — and openness to the Spirit moving in the church.

MS. TIPPETT: And that is a special passion of yours — Isn’t it? — the church working directly with people who are hurting and at risk?

DR. FRANKLIN: One Sunday morning at the St. Paul Church of God in Christ in Chicago, I was a student, graduate student at the University of Chicago, and I was a member of an adult Sunday School, you know, class. The pastor had this insight, once again, I think the Spirit moving. And he came to me. He just sort of called me out of his class. And he says, `I just want you to follow me.’ And we walked through the congregation of classrooms, and he just sort of interrupted each class, barged in as it were with me standing there behind him, and asked the teacher, `Do you have any boys in this class that are disruptive or creating problems?’ And in each instance, all of them had one or two. He call these guys out and, `You follow us.’ So he looked at me and said, `OK, this is your class now. Work with these guys.’ And he walked out. I thought, `Wait a minute. This is not what I was bargaining for.’ And so there I was without curriculum, without a lot of training. I mean, I’d grown up on those mean streets, so I knew something about what these guys were facing. So I sort of fell back on that and said, `Now I want you guys to tell me what kind of week you’ve had.’ And in every instance, there was some significant issue of conflict within the household of, `My mother’s boyfriend who uses inappropriate language in our presence, and she puts up,’ and we just had this list: Violence, conflict, etc, interactions with the police, all sorts of this. And they just felt like no one was hearing their story.

MS. TIPPETT: Real life.

DR. FRANKLIN: Exactly.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. FRANKLIN: And we fashioned our own rituals, and it was really quite extraordinary. We’d always end with a prayer, and we’d sing “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” that famous, what we call, the negro national anthem. And one week, we were rushing. We were late, and we — I said, `We’re just going to say the prayer and run on.’ `No, no, no. We have to sing the song.’ And it’s funny. I mean, here are these young guys, these 13-, 14-, 15-year-olds off tough streets of Chicago, insisting that we observe sacred ritual, that this was a part of the order in their chaotic lives each week, and they didn’t want to miss that moment. And it became for me a signal to these middle-class affluent congregations and those aspiring to become that that we may have to move out of our comfort zone and out of our usual paradigms for formation of children in character in order to reach folks. And we got to listen to them more.

MS. TIPPETT: Emory University theologian Robert Franklin. This is Speaking of Faith, and I’m Krista Tippett.

Today we’re exploring the nature and meaning of Pentecostalism, the fastest growing form of Christianity in the world. In parts of Latin America, which were traditionally Roman Catholic, as much as one-third of the population has converted to a Pentecostal Christian identity.

MS. TIPPETT: When you were at Harvard — you know, Harvard is a place we associate with profound education about just about everything, but do people at Harvard understand Pentecostalism?

DR. FRANKLIN: They are curious. They are curious. In fact, you know this name, Harvey Cox, a faculty member at the Harvard Divinity School, who, in fact, has taken Pentecostalism quite seriously and thought, `Gee whiz. We thought the energy for renewing Christianity in the world would come from Eastern mystical traditions.’ And 20 years ago, that’s where all the energy was. That’s where Harvey Cox himself was.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

DR. FRANKLIN: But it now appears that these energies are coming from the Southern Hemisphere, from Africa, Asia, South America. And when we look at the faith of these people, it is, as you put it so well, incarnational theology. It is the Spirit moving in people, causing people to look at how they organize their ethical priorities, how they spend their money, how they shape their lifestyles, in trying to work for democracy from from the village up, trying to ensure that girls receive education as well as boys. And those practical expressions of this kind of democratic energy that Pentecostalism…

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, isn’t democrat…

DR. FRANKLIN: …and it’s anti-authoritarian kind of movement, it’s tremendous.

MS. TIPPETT: Yes, right. And isn’t it interesting that it started in this country. It’s been gone out and energized the rest of the world. Now it’s ricocheting back…

DR. FRANKLIN: Indeed.

MS. TIPPETT: …and they’re taking it seriously…

DR. FRANKLIN: You put it well.

MS. TIPPETT: …at Harvard…

DR. FRANKLIN: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: …because of…

DR. FRANKLIN: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: …of this — how successfully exported it’s been.

DR. FRANKLIN: Absolutely. I should mention also that I’ve just returned from Brazil and just some other travel in Southeast Asia. But it was particularly in Brazil in Trinidad, other places in the Caribbean that I began to see now firsthand for myself what Pentecostalism is doing there both in terms of its own independent expressions, but also in seeking to kind of re-energize both Catholic and protestant presence in that country, so…

MS. TIPPETT: You know, I think that the way Pentecostal traditions are really transforming the face of the Christian church in much of the world is something that’s going to be extremely important as we move farther into this century. Tell me if I’m simplifying things too much, but it seems to me that one of the fundamentals of Pentecostalism is that God can speak to anyone directly…

DR. FRANKLIN: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: …and that that is so empowering for people who have been also — oh, what’s the word I want to use? — oppressed or at least not powerful in their societal context. Does that — I mean, did you see that. Is that part of what you’re talking about?

DR. FRANKLIN: Yes, absolutely, yeah. I, you know, traveled to the outskirts in a part of the country in the state of Salvador, the highest concentration of Africans who were brought to work the sugar plantations. And so an enormous Afro-Brazilian presence there. And I was — had particular interest in what was happening in terms of culture and civil society. We hear so much about violence in the so-called favelas, the slums of Brazil. But what I saw in terms of this relatively small Pentecostal tradition was almost a reversal of what I would encounter in the typical Pentecostal congregation in the United States. The men began worship so that the women could then come on. And then, you know soloists, singers, and then the sermon delivered by a wife of a — this is incredible. I mean this is absolutely…

MS. TIPPETT: In a so-called backwards society, right?

DR. FRANKLIN: Indeed. Indeed. And the men sat there and quietly took notes and listened and supported the female preacher. And I just thought, `This is precisely the kind of innovation that I think, you know, Pentecostalism allows and cultivates and then exports in areas appropriated by other traditions to their good. I guess my concern would be that people who might be at first blush inclined to dismiss this, `Oh, yeah, this is just this, you know, kind of exotic expression of exotic people in our country or from outside the country.’ Look again at the roots of our own traditions. European immigrants who came of German pietism, of all of these traditions that had his kind of energy, what became of the energy is the question I’d invite people to reflect on. And I think a lot of us suppressed, were afraid of, channeled it in other ways. And yet that was, in fact, the same energy that I think Pentecostals said, `What if we were to just sort of go with the flow of this and see where it takes us, not letting it kind of drive us into some sort of sect-like or cult-like, you know, strange anti-Christian phenomenon, but to, in the Spirit of Christ, read the scripture through the kind of openness to this energy and ongoing revelation..

MS. TIPPETT: Robert Franklin is a distinguished professor of social ethics at the Candler School of Theology at Emory University. This is Speaking of Faith. After a short break, we’ll speak with Margaret Poloma, a sociologist and practitioner of Pentecostalism. She coined the term `main street mystics in her new study of a recent charismatic event, the Toronto Blessing. I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us.

Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, conversation about belief, meaning, ethics and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today, Pentecostalism in America. Pentecostal Christianity began on the American frontier at the beginning of the 20th century. It is the fastest-growing expression of Christian worship and belief in the world. Pentecostalism describes the form of Christianity not bound by doctrines or denominations. A Pentecostal Christian may or may not be a fundamentalist, for example, and in many cases, the fervent individualism of the Pentecostal experience finds itself at odds with a strict or a fundamentalist approach. My next guest, Margaret Poloma, was raised Roman Catholic and practices a charismatic Christianity. As a sociologist, she studies a new wave of the Pentecostal movement which is said to be unfolding now. It is commonly called the Vineyard Movement. Vineyard leaders stress signs and wonders, a phrase that recurs in the New Testament description of the first Christian Pentecost recorded in the Book of Acts.

READER: `And in the last days, it shall be,’ God declares, `that I will pour out my spirit upon all flesh and your sons and your daughters shall prophesy and your young men shall see visions and your old men shall dream dreams. Yay, and on my men servants and on my maid servants in those days I will pour out my spirit and they shall prophesy. And I will show wonders in the heaven above and signs on the earth beneath, blood and fire and vapor of smoke. The sun shall be turned into darkness and the moon into blood before the day of the Lord comes, the great and manifest day. And it shall be that whoever calls on the name of the Lord shall be saved.’

MS. TIPPETT: One of the most highly publicized so-called signs and wonders of recent years is an ongoing phenomenon known as the Toronto Blessing. It began on January 20th, 1994, in the Toronto Airport Vineyard Church. Most nights since then, there have been services at which people say, `This spirit moves in new ways.’

Millions of pilgrims visited the services at their peak in the 1990s. On any given night, people from as many as 30 countries were present. Margaret Poloma is a sociologist based in Akron, Ohio. She began hearing about Toronto right away, but for some time, she was skeptical.

MARGARET POLOMA: In 1994, I began hearing rumors about a revival going on in Toronto, and since I’ve been a student of the Pentecostal charismatic movement and have seen many revival and many of them fizzle. And sometimes you were more hyped than if a reality. I didn’t have any particular interest in going to Toronto. A couple of months later, I decided to go over to the local Episcopal church for a service. It’s a charismatic Episcopal church. And that particular evening, the priest had just returned from a visit to Toronto, and they were reading the passage from Ephesians about knowing the heights and the depth and the breadth of God’s love. And then they kept saying, `That is the message of Toronto. That’s the message of Toronto, knowing God’s love.’

MS. TIPPETT: Two weeks later, Margaret Poloma journeyed to the Toronto Airport Church to experience it for herself. She describes the scene she encountered with one word: Pandemonium.

DR. POLOMA: Of course, people were doing the things they usually do at charismatic kinds of services. Their hands up. Some people were kind of swaying, you know, very — a lot of singing, a lot of exuberance, but I also saw people shaking like I never saw people shake before. I saw people just falling to the ground all over the place which I had seen. That’s what they call resting in the spirit, being slain in the spirit. At Toronto, they simply called it carpet time. So when you wanted to walk across the floor, you might be walking across all kinds of bodies just to get to the other end of the room and nobody seemed to care what you were doing. There was a lot of laughter. That also was very much of a trade of Toronto, so much so that it was sometimes called the laughing revival.

MS. TIPPETT: There was a term holy laughter that was s…

DR. POLOMA: Holy laughter, right.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. POLOMA: I mean, you couldn’t help but laugh standing there looking at the people, but somehow when I was laughing, I know I wasn’t doing what they were doing…

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

DR. POLOMA: …their laughter came from a far deeper place, you know, a real belly laughter and over nothing. I mean, nobody was telling jokes. There wasn’t anything particularly funny, and you could have one person lying on the floor crying and another one laughing. And there just was not one single phenomenon that was going on which is why I use the term pandemonium.

MS. TIPPETT: As a person who is part of this Pentecostal tradition but also as a sociologist who studied it, tell me what you’ve come to make of what is happening there and what it means.

DR. POLOMA: If you just stop for a moment, you also knew that there was something else that you could sense. Again, depending on the person, but I’ll never forget Leslie Scrivener, the reporter from the Toronto Star, when she came in and when she wrote of her article in 1995 about the Toronto blessing, she described it pretty much the way I’ve been trying to describe this kind of pandemonium, but then over that, she saw kind of peace. So there was something else that could sense if you just stopped and didn’t get too caught up in what’s happening here, just — you could be sitting in the midst of this noise or seeming noise and there’s still some other experience you could have even if you weren’t participating in that.

MS. TIPPETT: So how have you come to understand what that peace is about or what it all means?

DR. POLOMA: Well, again, I do it on two levels. Part of me does it as a believer, but when I was writing the book, Main Street Mystics, I was very interested in trying to explain as much as I could of it by just looking about — what we know about human nature. And certainly post-enlightenment humanity has been so devoid of feelings, of opportunities for catharsis, and yet I truly believe that we, as human beings, are wired in such a way that we do require these kinds of responses, not only emotional response but even physical responses. And I think at one time, certainly religion could provide that. It certainly does in other cultures, but in our own culture, I think that much of our faith is an intellectual exercise, particularly for those of us who are more scholarly. We’ll make it a matter of belief: Does it make sense? Is it rational? When this kind of a movement happens, it doesn’t even make sense to ask those kind of questions. So I ask different questions.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, and what are those questions?

DR. POLOMA: OK. I ask — I try to look at what is the role that the physical body might play in releasing some stress. What role does catharsis play in our well-being? There have been authors in writing about catharsis saying that other — certainly in earlier times, there were opportunities for catharsis where you could enter into these seemingly strange emotional things but not get sucked into too much, but you had a nice healthy distance. You could appreciate and feel what was happening and then go on with your daily life. But, again, religious ritual used to do that.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

DR. POLOMA: But I think with much of Protestantism to use a quip by Charles Kraft who’s an anthropologist at Fuller, he says, `Evangelicals are the only ones’ — and I would say Protestants — `are the only ones who center their religious services around a lecture.’

MS. TIPPETT: Right. And squeeze themselves into pews where you have to sit up straight.

DR. POLOMA: Exactly. Exactly.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

DR.POLOMA: You’ve got it.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

DR. POLOMA: So Toronto offered an opportunity for something different.

MS. TIPPETT: Here are the voices of some visitors to the Toronto Airport Church in October 2003.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN: I came with a group of friends from church. There’s 18 of us, my church in South London in England. Yeah, I think their kings get all the trappings of religion out of the way and just op — however, have sort of an open channel with God.

UNIDENTIFIED WOMAN: Well, it’s very personal with God. So I spend a lot of time on the carpet. The whole leadership has a priority to let the Holy Spirit have its way and that’s not putting God in a box. So that’s great. I love it.

UNIDENTIFIED MAN: You walk in the doors, you can feel God here. You can feel the Holy Spirit here. It’s just tremendous. Just a tremendous feeling.

MS. TIPPETT: And you actually talked to people who’d had that experience and then sort of moved on with their lives — Right? And I’m…

DR. POLOMA: I’d say…

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. POLOMA: …yeah, probably the majority of people have the experience and moved on with their lives.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. And tell me how then what did they tell you or what did you see of how that experience affected the life, the days, weeks, years after it? Did it?

DR. POLOMA: People claim that they experience God in a deeper way, that they came to know him in a way that they had not known him before. They came to know the father’s love in a fresh, new way. They came to know Jesus in a new way. So these religious experiences, and that’s exactly what they were, they were perceived experiences of the divine that certainly changed their approach to faith or at least deepened it. I also had asked questions about whether it changed some of their behavior, like, are they giving more money to the poor, are they spending time visiting visitors? You know, I asked different questions like that, and many — a significant minority said they were. Now whether they were or they weren’t, I don’t know, but what a — I could look and see that people who went to Toronto truly believed that it changed their spiritual and religious lives in some significant ways. And they believe that spilled over into relationships particularly…

MS. TIPPETT: And how…

DR. POLOMA: …that it changed their marriages. A lot of testimonies about changed marriages.

MS. TIPPETT: What’s the line from that experience to the improved marriage? What was the dimension of that that flowed into their lives?

DR. POLOMA: Knowing God’s love and then being able to love the spouse in a deeper way, love their children, love friends, co-workers. I really think that love was very central to this revival, knowing the love of God, the very thing that drew me there to start with, you know, that call. You don’t really know how much I love you, and then having those experiences that centered around God’s love.

MS. TIPPETT: So I was going to ask you this real public radio question. You know, you talked about how modern religion has focused so much on the intellect and not on the body and so I was going to ask you whether still this Toronto experience had intellectual content. I think, again, you know, what you’re pointing at is the experience of love in human life…

DR. POLOMA: Which is important and something we don’t like talking about too much unless it’s romantic love.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

DR. POLOMA: You know, I think that that’s part of what drew me to the study that I’m doing right now which is also on a Pentecostal charismatic group known as Blood and Fire, and they’re a ministry and say they’re a church of the homeless in Atlanta. And these people are still walking out a kind of Toronto. They really walk it out in their daily lives. And the focus of their ministry is the really downtrodden and how their lives can be changed by knowing — coming to know the love of God.

MS. TIPPETT: Sociologist Margaret Poloma of the University of Akron. I’m Krista Tippett and this is Speaking of Faith.

In a small cinder block building, about 30 members of the Bread of Life Pentecostal Church of God meet for Sunday service in south Minneapolis. As the choir sings, some people move and dance and prayer may erupt spontaneously into speaking in tongues. At this church, community involvement is foremost. Meals are prepared. Work is underway to find funding for teen-aged mothers and there are projects to help addicts and alcoholics in the neighborhood.

UNIDENTIFIED WOMAN: I want to thank you for all the work you have done. We have just received word that our 501c3 was approved, a non-profit organization, and we will be working with the community even more than we have been and we’ll have more activities with children, with single mothers and with others who are in need in our community. So I just want to thank you for the hard work that you’ve been doing getting that off the ground.

MS. TIPPETT: The Bread of Life Church like many communities in the Pentecostal movement is unaffiliated with the denomination or larger church hierarchy. The Assemblies of God is the largest explicitly Pentecostal denomination. As a scholar and practitioner, Margaret Poloma is both appreciative and critical of Pentecostal charismatic movements.

DR. POLOMA: What happens not only to the Toronto movement but certainly happened in Pentecostalism, I would say it happens in religion in general. Abraham Maslow made the observation, the humanist psychologist — made the observation that all religious institutions are born out of somebody’s religious experience. He calls it a peak experience. So when we begin to consider the founders of great religions, they had phenomenal kinds of experiences.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

DR. POLOMA: And their followers probably had phenomenal experiences.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

DR. POLOMA: Look at Christianity. Jesus had experiences with God. People who followed him had experiences. The early church had experiences, but often what happens is that the experiences become ritual. They become a memory. They become something that is celebrated only as memory rather of something that could be had today. And that phenomenon that I’ve called — I’ve termed in many of my works, the routinization of charisma, the making charisma routine, institutionalizing it to the point where we talk about it, we have a history of it, but nobody’s experiencing much of anything. So that particular process seems almost inevitable. I mean, as long as I’ve been studying the Pentecostal charismatic movement, I’ve seen how quickly it routinizes.

MS. TIPPETT: Even in a Pentecostal movement you’re saying.

DR. POLOMA: Oh, definitely.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

DR. POLOMA: Pentecostal movements.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, that’s a little interesting.

DR. POLOMA: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: Uh-huh.

DR. POLOMA: I mean, they may still have vestiges of it. At least their belief system is open to it. They haven’t gotten to the point where some churches have where you’ll say those things don’t happen or some churches say they never happened.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. And you’re talking about healing…

DR. POLOMA: I’m talking about healing prophesy.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. Mm-hmm. Speaking in tongues maybe.

DR. POLOMA: Speaking in tongues…

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

DR. POLOMA:…right. So if we’re looking at those phenomenon — you know, the Assemblies of God, for example, is a good example of a denomination that has worked to try to maintain the charisma but I’m not sure how successful they’ve been. Even now, their main point is trying to continue to give importance to tongues and to give importance to their ritual — their definition — their theological definition of tongues when most of their people aren’t even speaking in tongues anymore.

MS. TIPPETT: OK. And I want you to give me your definition — the way you’re using the word charisma is not the sort of slang use of the word charisma. You’re drawing on this word charism, right?

DR. POLOMA: I’m drawing on the word, yes. Right.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

DR. POLOMA: Charism and particularly as used in being in the New Testament and First Corinthians particularly, 12, 13, 14.

MS. TIPPETT: This is describing spiritual gifts that…

DR. POLOMA: The spiritual gifts, right.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

DR. POLOMA: So we will be talking about certainly tongues but also healing, prophesy in its different form. Another word for prophesy would be revelation, miracles.

MS. TIPPETT: Sociologist Margaret Poloma. Her book is Main Street Mystics: The Toronto Blessing and Reviving Pentecostalism. Here’s a reading from the New Testament Book of First Corinthians, a pivotal text for Pentecostal Christians.

READER: To each is given the manifestation of the spirit for the common good. To one is given through the spirit the utterance of wisdom and to another the utterance of knowledge according to the same spirit. To another faith by the same spirit. To another gifts of healing by the one spirit. To another the working of all miracles. To another prophesy. To another various kinds of tongues. To another the interpretation of tongues.

MS. TIPPETT: I wonder through your personal experiences and the proximity you’ve had to these events through your work, tell me then how it has affected you and your faith and the way you live that out.

DR. POLOMA: OK. Pentecostal is a great — or Pentecostal charismatics are great storytellers. There’s this really narrative theology if they’re doing it right. So I can’t help but be a storyteller, and so I always have my stories to illustrate, and when you’re talking about — perhaps when we’re considering the tension that might exist between the rational kind of scholarship that I’ve been trained to do and I was trained as a sociologist of religion, became an agnostic using the tools of my trade, and became a believer only through experience. Now I reason my way to non-belief but I could not reason my way to belief.

MS. TIPPETT: You know the word mystics…

DR. POLOMA: Uh-huh.

Ms. Tippett: …”Main Street Mystics” — it’s an intriguing use of the word mystics to describe these — this charismatic movement that has arisen out of pandemonium. Tell me how you came to use that word and is it a new — is it stretching that definition of that word.

DR. POLOMA: Oh, I don’t think so. Not at all. I think that if you read the literature on mysticism, one of the definitions is is a mystic is someone who hears from God. A mystic is one who hears from God. And — or hears from the divine or hears from something not natural. It depends which group you’re in, but, I mean, certainly in Christian literature, that’s pretty much what a mystic is. And ever since my beginning days in the charismatic movement I wished that people would start writing about mysticism and the charismatic movement in the same articles. And some people in the charismatic movement wouldn’t even like the term mysticism. They would see it as being something they’re not. On the other hand, other people have a different sense of mysticism, but all I mean by it is someone who hears from God. And I think that — in fact, I know based on other research I’ve done that the majority of Americans believe they hear from God at least sometime in their life.

MS. TIPPETT: They’ll answer that question with a yes at some point in their life.

DR. POLOMA: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. OK.

DR. POLOMA: I mean, I’ve done surveys and that comes through on surveys on prayer. We know that if you ask people if they hear from God, at some point they will say yes, maybe even within the past year. A much smaller percentage — I think only 9 percent hear God regularly. Charismatic Pentecostals are among those people that hear God regularly, or at least many of them are because there’s always fresh outpourings of this charisma if you will. The waves keep coming just as they did in Toronto because Toronto isn’t the only time this kind of revival happened this century — or in the 20th century and it’ll probably happen again. That tends to, if you will, invigorate the whole Pentecostal charismatic perspective or world view which is so at odds with modern society.

MS. TIPPETT: Well — and I want to ask you if that fact that it is at odds with modern society is the reason that on the one hand this Pentecostal/charismatic experience is part of the religious experience of a significant percentage of Christians in this country, right?

DR. POLOMA: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: And at the same time, I think to the rest of the Christians in this country or people who are nominally Christian or of other religions. It feels extremely foreign and exclusive in a way and also maybe crazy, right?

DR. POLOMA: Sure.

MS. TIPPETT: So why do we have these two polls of perception of what this means?

DR. POLOMA: Oh, I think and many psychologists of religion as well as other scholars have made note of this that probably any church has its mystics and it has its institutionalists. It has its people that defend the denomination and the institution beyond any measure. And they’re the ones who fight over the hymn books and how many candles should be on the alter. On the other hand, you also have the mystics who are experiencing God. It may not be charismatic at all by — in title — in terms of label, but their faith is more based on that relationship with God. And in the case of Toronto, it showed that you didn’t even have to be really be quiet on the outside, if something happened to quiet you on the inside, because people had some dramatic experiences with God speaking through them so much so that it propelled them into different kinds of actions that might have seemed foolhardy, leaving jobs, you know, starting a new church, going off to the missions.

MS. TIPPETT: When you talk about God talking to you or God talking to someone, how do you know? You know, we have horrific examples of people who do terrible acts in the name of doing God — of following God’s will, right?…

DR. POLOMA: Right.

MS. TIPPETT: …hearing the voice of God, having servitude about what God would have them do. In our time, it seems that there is a very real danger that we can associate with that wisely. So how do you put that into the context of what we’ve been talking about?

DR. POLOMA: Yeah. I don’t have any research to back this up, but my own sense is that often when people are so sure that God told them something and particularly when they try to impose that on other people, I’m not sure how much they’re hearing God because once you get into this relationship with God, humility is a byproduct. I mean, God may take us in our arrogance and kind of allow us to begin interacting with him, but I don’t know that that continues. I don’t know how it can continue without developing some sense of humility and a humble spirit.

MS. TIPPETT: So for you an absence of humility, of thought and action would be a sign that, in fact, God’s voice…

DR. POLOMA: Yeah.

MS. TIPPETT: …had not been heard or…

DR. POLOMA: When I hear somebody, even in the Pentecostal charismatic tradition that starts in on God and they’ve got all the answers, I stay far away because no one can know God that way. We just get glimpses. We see through this glass darkly, but at least the Pentecostal charismatic approach to Christianity has allowed me a means to see something which be nothing at all, but I think your right. Many people are fearful and I was, too. What if you go crazy? People have gone crazy in the name of God, but the longer I’ve walked this path, the more people I’ve known more — that’s not what’s happened. As you had this relationship with God, there is that tempering. There’s a gentling. There — you know, I may not seem all that gentle but you’ve should have seen me before.

MS. TIPPETT: Margaret Poloma is professor emeritus of sociology at the University of Akron. Her book is Main Street Mystics: The Toronto Blessing and Reviving Pentecostalism. Earlier in this hour, you heard Robert Franklin, presidential distinguished professor of social ethics at the Candler School of Theology at Emory University.

We’d love to hear your comments on this program. Please write to us at [email protected]. You can also reach us through our Web site at speakingoffaith.org. While you’re there, you’ll find complete audio of this program as well as our previous programs and book and music lists.

[Credits]

I’m Krista Tippett. Please join us again next week.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.