Anoushka Shankar, Roberta Bondi, Stephen Mitchell, et al.

Patterns of Prayer

In recent years, the practices of prayer have been evolving for many religious traditions. Even western medicine is looking at prayer as it expands its concept of healing. In this program, we consult several people from a variety of practices about the role of prayer in their lives.

Image by Alfonso/Flickr, Attribution-NonCommercial.

Guests

Gregory Plotnikoff is medical director at the University of Minnesota's Center for Spirituality and Healing, on the promises and limitations of the use of intercessory prayer in medicine.

Michele Balamani is executive director of the Baraka Pastoral Counseling Center in Maryland, on how and why prayer improves the outcomes of mental health care, especially in African-American communities.

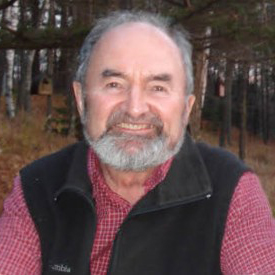

Michael Dennis Browne a poet, on his Centering Prayer, a Christian contemplative practice akin to meditation.

Anoushka Shankar is a musician, actress, and author of Bapi, The Love of My Life.

Stephen Mitchell is an author, poet, and translator. His works of translation include The Selected Poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke, Gilgamesh, and Full Woman, Fleshly Apple, Hot Moon: Selected Poems of Pablo Neruda. Mitchell translated The Selected Poetry of Yehuda Amichai with Chana Bloch. Image by Brie Childers.

Transcript

November 27, 2003

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: This is Speaking of Faith, conversation about belief, meaning, ethics and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “Patterns of Prayer.” Prayer is a universal aspect of religion found in primitive and modern cultures alike. It is a primary expression of the human longing to come into contact with the sacred, and it is an undeniable part of American life. In times of crisis and celebration, Americans pray. In fact, sales of prayer books of every variety have been exploding for years. Even Western medicine is looking at prayer and meditation as it expands its definition of healing. Today we’ll explore patterns of prayer in a variety of traditions and in the first person.

[Excerpt from “Veni sancte spiritus”]

MS. TIPPETT: The word `prayer’ comes from a Latin root meaning `to entreat.’ This is an eighth century-prayer in Latin, “Veni sancte spiritus,” `Come Holy Spirit,” sung by the Spanish monks of Santo Domingo de Silos. Seven times a day every day of the year, like their brothers in faith for over 1,500 years, these monks pray through Gregorian chant. Americans bought this recording by the millions in the late 1990s. In their practice of prayer, many modern Americans are increasingly drawn to ancient teachings, and theologian Roberta Bondi is part of this movement. She’s written beloved, no-nonsense books about how she learned to pray when she discovered the writings of the earliest Christian monastics.

ROBERTA BONDI: Sometimes it seems when I’m talking to people about prayer that one of the main points I have to keep making over and over is there is no right way. The important thing is to find your way, and this was something that I learned from the abbas and ammas of the ancient desert.

MS. TIPPETT: The abbas and ammas were Christians from all walks of life who, around the fifth and sixth centuries, retreated from a church which they felt had been corrupted by its own power. They went into the deserts of Egypt and Syria to pray. Politicians, generals and peasants sought their advice on matters both spiritual and secular. `Abba’ and `amma’ are Semitic words for `father’ and `mother,’ and their insights were collected by their followers and passed down across centuries as the sayings of the fathers. The sayings transformed Roberta Bondi’s image of God and the abbas and ammas became her teachers. Still, even she held prayer at a scholarly distance until a crisis of confidence early in her marriage to her husband, Richard. One day, as often, he was late coming home.

DR. BONDI: I was sitting there on the couch and all of a sudden the abbas from the ancient desert started saying to me, `Roberta, Roberta, we have something to say to you,’ and I said, `Shut up and leave me alone. I’m worrying.’ And — and they said, `Oh, oh, no. Come — come on now. Come on. Listen.’ `Shh, shh, I’m worrying. Leave me alone.’ And finally, I said, `All right. All right. What do you have to say?’ And they said to me, `Well, now, you know that the main thing we’re doing out here in the desert is prayer and you have spent a lot of time studying us and working on us, and you might consider whether this might be something for you.’ And I said to them, `Oh, come on. Now look, I — I am a rational, reasonable woman and I’m an academic, and this is — what you’re suggesting just is not really for me.’ And the answer to that was, `Ho, ho, ho, you might also consider as part of this that you have put Richard into the place of God for you. You know how we say that no one or no thing can fill that hole in your life except God, that your identity rests only in God and that all other loves come out of that, and that if — and that no human being can ever fill that. Of course you feel the way you do.’ So I was very embarrassed, because I knew, of course, instantly that they were right. So I said, `OK. All right. All right. I’ll try it.’ So well, first, I let Richard come home and then yelled at him a little bit. And then I went out and got a book that had a pattern of prayer in it that was similar to what was used in the early church, and that was what started me on my discipline of prayer. And I can say several things that I learned out of that that I like to share with others, and one of the things is you don’t need any kind of noble reason or highfalutin or serious reason. Any reason to begin a pattern of prayer is a good reason because prayer is about everyday life; it isn’t the great spiritual mystery that is too high and lofty for the likes of us.

MS. TIPPETT: You often talk about the importance of just showing up for prayer.

DR. BONDI: We often have a kind of notion, as part of this highfalutin, noble picture of ourselves as prayers, that when we pray we need to be completely attentive and we need to be fully engaged and we need to be concentrating and we need to be focused. But the fact is, if prayer is our end of a relationship with God, that’s not the way we are with the people we love a large portion of the time. We simply are in their presence. We’re going about our lives at the same time in each other’s presence aware and sustained by each other, but not much more than that. Well, let me tell you a story about when I first started teaching in the seminary where I teach now. And I would just find when I came home at the end of the day I would be so exhausted that I could hardly contain myself. And I would be met at the car, usually, pulling into the driveway, by my two children and my husband, who would all come out to tell me all the things that had gone wrong in the day, like the washing machine had overflowed and that the rug in the dining room was soaking wet. And I would think, `Oh, I just want to go back to the school,’ and then I would tell myself, `Well, if I could just bring a sandwich to school and I could just eat my sandwich and be quiet a little bit before I came home,’ and then they could have their supper and I’d just get there after it was all over. But of course, this was just a fantasy. I would come into the house and Richard and I would fix supper, and then we would sit down and eat and I would fall asleep with my head in the mashed potatoes. But the fact is that I knew all along that however it was, it was better that I was there than if I wasn’t there, that my family needed me; that being part of a family means showing up for meals. And prayer is like that. However we are, however we think we ought to be in prayer, the fact is we just need to show up and do the best we can do. It’s like being in a family.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith, with a program on prayer. I’m in conversation with theologian Roberta Bondi. In her teen-age years she stopped praying to the judgmental God of her childhood. What she discovered as an adult through the desert fathers and mothers was a God of compassion, one who forgives men and women more easily than they forgive each other or even themselves. This was a God she could pray to.

READER: The saying of Abyssino, from the sayings of the desert fathers. If a man wants God to hear his prayer quickly, then before he prays for anything else, even his own soul, when he stands and stretches out his hands towards God, he must pray with all his heart for his enemies. Through this action, God will hear everything that he asks.

DR. BONDI: You know, one of the abbas was asked one time whe — which was the most difficult virtue to acquire, and he went through the whole list of one virtue after another, and then he concluded by saying, `But prayer is the hardest of the virtues because prayer is warfare to the last breath.’ In prayer, we — we are likely, and it’s certainly what we want, to see ourselves as we really are. We can’t expect that we are going to be healed of the deep wounds of our heart without seeing what those wounds are. It’s also not a peaceful activity when we discover or come face-to-face with the reality of the world.

MS. TIPPETT: Talk about some of those images you find in Scripture that it’s all right for us to struggle and even fight with God and even nag and demand things that feel important to us.

DR. BONDI: Well, one of my favorite images from Scripture has — since the time I was a child, was always Jacob wrestling with the angel.

READER: That same night Jacob arose and took his two wives and his two maids and his 11 children across the ford at the Jabbok. He took them and sent them across the stream and likewise everything that he had. And Jacob was left alone. And a man wrestled with him until the breaking of the day. When the man saw that he did not prevail against Jacob, he touched the hollow of his thigh, and Jacob’s thigh was put out of joint as he wrestled with him. Then he said, `Let me go, for the day is breaking.’ But Jacob said, `I will not let you go unless you bless me.’ And he said to him, `What is your name?’ And he said, `Jacob.’ Then he said, `Your name shall no more be called Jacob, but Israel, for you have striven with God and with man and have prevailed,’ and there he blessed him.

DR. BONDI: This is, I think, my very favorite because it has all the elements of real prayer: God sneaking up on Jacob, you know, because it’s really God — this angel is — sneaking up on Jacob unexpectedly in the night, which is often when God comes to us with the anxiety-producing information about ourselves or about our situation. Jacob’s absolute persistence in saying, `Look, all right, you started this. I’m not letting you go.’ And his absolute, steadfast commitment to the fact that if he — if he ha — hung in there, there would be a blessing in it, which is my experience over and over and over. But — but wrestling is the way it is a lot of the time. I have a friend who plays in the Atlanta Symphony, and I — someone asked him once what it was like to play piccolo in a great symphony like the Atlanta Symphony, and he said, `Well, it’s actually long stretches of boredom interspersed with short periods of pure terror.’ And I wouldn’t say it quite like that, that prayer is like that, but I would say that prayer is long periods of ordinary shared life together with intense periods of wrestling with really serious stuff that can scare us to death but can also bring us into real life with God and real life with ourselves in a way that we can’t otherwise have it.

MS. TIPPETT: Roberta Bondi is professor of church history at the Candler School of Theology at Emory University in Atlanta.

[Excerpt from “Woodsong C”]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is Speaking of Faith on “Patterns of Prayer.”

[Excerpt from Muslim prayer]

MS. TIPPETT: You’re listening to the sounds of a Muslim man leading his family in prayer at home. Observant Muslims pray five times each day. Muslim prayer involves the whole body in preparation and posture. And wherever Muslims find themselves in the world at the appointed time for prayer, they turn towards Mecca, which is in modern-day Saudi Arabia. Muslim prayer is in every way an expression of the essential virtue of surrender before the one god, Allah.

For centuries, prayer was viewed in the West purely as a matter of faith, but even this is changing. There are now hundreds of scientific studies about the effects of prayer on health. A new field, neurotheology, has documented physical changes in the brain as a result of prayer and meditation. Physicians who advocate prayer and spiritual practice have created best-sellers like Prayer is Good Medicine. Dr. Gregory Plotnikoff is the founding medical director of the Center for Spirituality and Healing at the University of Minnesota. And as such, he is part of a growing movement in hospitals and medical schools across the country. Before beginning his training in internal medicine and pediatrics, he pursued a master’s of theological studies at Harvard Divinity School.

GREGORY PLOTNIKOFF: When I arrived in medical school, I was stunned. Nowhere in the curriculum was healing ever even mentioned.

MS. TIPPETT: So it was what as opposed to healing? It was medical care or…

DR. PLOTNIKOFF: Well, you know, the technical correction of aberrant physiology in the gallbladder in bed 43. Clearly, it’s important to focus on the biomedical, but one also has to recognize that every focus can also have its own blind spots. What’s highlighted may be true and important, but what is blinded may be as true or even more important.

MS. TIPPETT: Many of the most influential spiritual studies in medicine have to do with mysterious but quantifiable effects of intercessory prayer, which is petition on behalf of others. And Gregory Plotnikoff is experiencing the promises and the problems of using prayer as medicine.

DR. PLOTNIKOFF: The most publicized studies have involved Christian prayer groups outside of a hospital setting receiving a name — very non-direct — you don’t say what to pray for, but, `Here, keep this person in your prayers.’ That’s been one form. There’s another study — Elisabeth Targ at University of California-San Francisco did a study in patients with HIV and there was a wide variety of spiritual healers outside the Christian tradition, and yet in both these cases, positive results were documented.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, but — and I think what is fascinating about that also is that it’s not — it’s not actually the person who is ill who is praying, right? This goes…

DR. PLOTNIKOFF: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: …beyond our idea that spiritual health also can translate into or support physical health. This is people who this — the ill person does not know — often does not even know that they’re being prayed for.

DR. PLOTNIKOFF: Correct. So how do we make sense of this? This is — it’s not like a dose of penicillin. Something appears to be happening, and so it’s really a phenomenon that kind of challenges fundamental assumptions.

MS. TIPPETT: Is it true that one of the largest studies was this Byrd study? And…

DR. PLOTNIKOFF: Yes, the Randolph Byrd study, 1988, University of California-San Francisco, 393 patients admitted to the intensive care unit with a diagnosis of heart attack. Half received prayer; half did not. Statistically profound differences between the two groups.

MS. TIPPETT: The prayed-for people had much less congestive heart failure, right?

DR. PLOTNIKOFF: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: None of them needed ventilation or intubation, while 6 percent of the people who weren’t prayed for need that kind of — of intervention.

DR. PLOTNIKOFF: Yes. Statistically, there appeared to be significant differences between the two groups, and if you combined the groups in terms of those people who had a kind of a good hospital course, those who had a medium hospital course and those people who had a poor hospital course, the trend analysis was again very statistically significant. So that really got people thinking. They said, `Oh, my goodness.’ People started raising questions. Well, if prayer was a pharmaceutical it would be in every formulary in the country tomorrow.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. This would have been on the front page of the newspapers, right, this wonder drug…

DR. PLOTNIKOFF: Yes. Yes, the wonder drug.

MS. TIPPETT: …that could improve your prognosis.

DR. PLOTNIKOFF: And then a very s — people started asking questions. They said, `Can you really randomize God?’

MS. TIPPETT: Now what do you mean by that?

DR. PLOTNIKOFF: Well, it’s kind of like, well, half the group gets God; half the group does not.

MS. TIPPETT: And this would be really a critique from the perspective of faith, right, a faithful person questioning these…

DR. PLOTNIKOFF: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: …these results about prayer?

DR. PLOTNIKOFF: Yes. The scientist would question it to say, `Look, statistically the — these appear to be quite important but, you know, further analysis will show that there are methodologic problems and can’t leap to any conclusions. This is not definitive.’ But it raises some interesting questions. And since 1988, multiple studies have taken place to follow up on this. None have had the — as spectacular results. However, they all — many of the ones published show a trend towards positive results. Then people ask, well — they say, `Well, what is a positive result? Is it what we want? Is it what we think God wants?’ Let’s say we have a great prayer study — the world’s best study, randomized, double-blind placebo, multicentered U.S. trial, big numbers. Let’s say it comes out incredibly positive. What then? Well, maybe it would be ethically appropriate, then, for me to write a prescription. `Well, Mrs. Jones, for you, Psalm 49 three times a day.’ But the problem is prayer and faith are something completely different from aspirin, Amoxicillin. You can’t hand over faith. Faith is an answer that is best found rather than given; it’s something to be nurtured, all right? And that’s where I believe our greatest challenges are, is how can we support people when they’re facing incredible challenges — physically, emotionally and spiritually — in hospitals, in clinics, in nursing homes and elsewhere?

MS. TIPPETT: And something that has also been striking to me as I looked into this subject is the gap that there has been traditionally in our culture. For example, in one poll, you’ll have 84 percent of the general population who say they pray. And if you ask — and — but the population of physicians is less than that, and of psychiatrists and psychologists even less again, and that seems to be borne out again and again. Now is that changing as these prayer studies, for example, infiltrate their way into medicine?

DR. PLOTNIKOFF: That’s a good question. We don’t know. The new medical students — study after study of beliefs of new medical students show that they are actually very open to considering this. I think the culture is changing, and I — I — so I think that there may be discrepancies between older generations and younger generations within medicine about the power of beliefs and the meaning of prayer. In many ways, people were closeted about faith in their own life, closeted…

MS. TIPPETT: Physicians?

DR. PLOTNIKOFF: Yes, because I think physicians were keenly aware of the ethical challenges about bringing one’s own faith in — into medical practice. And I think physicians in general are keenly aware that, `Gosh, my answers are not your answers. My answers shouldn’t be your answers.’

MS. TIPPETT: Now that’s a good thing, right? That’s a good value.

DR. PLOTNIKOFF: Yes. Yes. I — I think it makes for very good medical care. But now there’s been more permission given to the importance of faith and to spirituality, so it’s not unusual to find people in every medical center in the country who — you know, who are willing to speak openly about this.

MS. TIPPETT: Do you think that your research in this field of prayer studies and your own attempt to integrate spirituality in medicine in your own practice have changed the way you pray or the way you think about what’s happening when you pray?

DR. PLOTNIKOFF: My experiences since becoming a doctor umpteen years ago have led me to conclude that prayer is incredibly undervalued, and that it has definitely become a richer part of my life. It’s one thing to pray for oneself, but it’s a whole ‘nother thing to pray for one’s own patients. Yes, I want to be as thorough as possible in doing the best biomedically, but, you know, that’s not all. I have a richer prayer life praying for others than I do for myself.

MS. TIPPETT: Gregory Plotnikoff is medical director of the Center for Spirituality and Healing at the University of Minnesota.

[Excerpt from “Spirit of God”]

MS. TIPPETT: Prayer is also being used now in intriguing new ways in mental health care. Dr. Michele Balamani is a psychotherapist and an ordained minister. She’s putting into practice new evidence that in African-American communities, like other cultures where religious institutions play a foundational role, prayer can improve the outcomes of psychotherapy.

MICHELE BALAMANI: I never force prayer. I always offer it, like I would offer you a cold glass of water or a cool glass of lemonade as an act of hospitality, and a way of us coming together to begin a work. What I would say is, `Are you comfortable if we begin with prayer?’ And then I would normally just do a very short prayer to indicate that we are in the presence of God, that we are coming together understanding that God is a healer, that we believe that God is health and we believe that God is hope. And we invite God into this room with us. And there is always from persons of faith a sort of relief and maybe a little bit of excitement that their doctor that they’re coming to understands them first on one level before we even begin to talk about what the problems are.

MS. TIPPETT: And what is different when prayer is part of the experience?

DR. BALAMANI: One example of what happens when prayer is present vs. when prayer is not present is that the — the connection that needs to take place in any therapeutic session takes place quicker, and so, you know, there — you don’t have to spend a lot of time — what we call in — in psychological terms establishing a rapport. And — and sometimes there is a deeper level of — of connection because prayer has been present. So prayer is a statement of faith. It also helps establish hope much quicker that maybe something different is going to happen here, maybe something even surprising is going to happen here. And I recently did an interview with the — the Post, and they interviewed one of my clients who shared her story of how she had been to so many therapists and that she always felt alienated, like there was some — something in her they couldn’t touch and there was something in them that she couldn’t touch. And so she would easily get frustrated and leave therapy. She would just stop, and it — it just didn’t feel right. And once she came to us, the fact that we prayed, she indicated, made all the difference in the world, that it told her volumes and that she began to cry in the first session because she was so happy and relieved that somebody understood that she was more than her problem, that she was a child of God with a problem, that she had a faith crisis as well as an emotional crisis.

MS. TIPPETT: I wonder what you, as a person of faith, have learned about the nature of prayer through these professional experiences you’ve had. How — how has this impacted your life of prayer?

DR. BALAMANI: Well, I have come to find prayer empowering and comforting for myself personally. I pray before I begin to see any person — not just pray with them; I pray for myself. And the reason is that many of the — the — of the challenges that I will be facing when persons come to me with their crises are beyond me in — in terms of just my flesh, you know, in terms of my training. And so for me, I first align myself — try to get in right relationship with God, understanding that this is not about me. I also am encouraged by the numbers of healings that have taken place because persons believed that it was more than just me and — and it was more than just them.

MS. TIPPETT: Dr. Michele Balamani is the executive director of the Baraka Pastoral Counseling Center in Largo, Maryland.

This is Speaking of Faith. After a short break, we’ll return with musician Anoushka Shankar on Hindu chant to many gods, and translator Stephen Mitchell on what he calls non-religious prayer. Also, poet Michael Dennis Browne on Centering Prayer, a Christian practice akin to meditation. I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us. Speaking of Faith is produced by Minnesota Public Radio and distributed by PRI.

Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, conversation about belief, meaning, ethics and ideas. Today we’re exploring some patterns of prayer in American thought and life. Beginning in the 1960s, many in the West began to look East for spiritual enlightenment. Not completely unlike the ancient Christian desert fathers, perhaps, they were searching for wisdom and alternative ways of life. In traditions such as Buddhism and Hinduism, they explored chant and meditation and they brought these practices back to America, where they flourished. In more recent years, this movement coincided with a rediscovery of other mystical traditions like Christianity’s contemplative prayer, Judaism’s Kabbalah and the Sufi mystics of Islam. The great sitarist Ravi Shankar became a spiritual and musical guru to many in the West, including most famously The Beatles, who sought him out in India. Ravi Shankar’s daughter, Anoushka, was raised mostly in London and California, and her life might be said to symbolize the modern flow of religious ideas from West to East and back again.

ANOUSHKA SHANKAR: I think I’ve distanced myself from a lot of the imagery of Hinduism, and I really do see what they explain it as, which is just sort of this sacred energy — this primordial — the ohm, the — the center of the universe, what — whatever you want to call it. It is just a universal energy, really, that we pray to, and people have to put images on it to make it easier, I think.

MS. TIPPETT: Now 21 years old, Anoushka Shankar performs all over the world with her father. Their first project together, when she was 15 in 1997, was a CD called “Chants of India.” It’s a collection of traditional Hindu Sanskrit prayers which her father set to music, and which former Beatles guitarist George Harrison produced. It includes several prayers that Anoushka recited in her childhood.

[Excerpt from “Chants of India”]

MS. SHANKAR: Yeah, a few of them are very close to me because I grew up saying them, and so those ones it was really nice to see them come out in this way. And I’m not singing it, but the way you chant it would be [foreign language spoken]. And it’s just a very basic prayer to Lord Ganesha, who you tend to always start auspiciously beginning anything with a prayer to him, so in that case, the album starts with a prayer to him, and the translation is: Oh, Lord Ganesha, of the curved trunk and massive body, the one whose splendor is equal to millions of suns, please bless me so that I do not face any obstacles in my endeavors. And the reason he’s always first is because he is known as the remover of obstacles, so at the beginning of a dance performance, people always start with a prayer to him. At the beginning of any venture, opening an office building, whatever, he’s the one that people tend to pray to to make everything go smoothly.

[Excerpt from “Chants of India”]

MS. SHANKAR: It’s still very much connected to nature. You know, most of our gods are connected to certain elements. We have the fire god, and he represents, you know, certain types of strength. The goddess of the water — she’s wisdom. You know, it connects to the idea of water and what it does — that type of power. And, you know, in that way we have thousands and thousands of gods and — and you pray to, you know, the type of thing that you’re looking for, I suppose. Beyond all of those minigods, of course, we have the trinity of Brahma the Creator, Vishnu the Preserver and Shiva the Destroyer, and they all, of course, symbolize different things. Their wives are different things; their children. But even beyond all that, I think what I find really fascinating about Sanskrit prayers is that it’s very much about the sound as well. If you look at the whole language of Sanskrit, I think it’s the only language in the world, maybe apart from Latin, where, like, the vibration of the way the words sound is equally as important as what you’re saying. And so when you’re chanting, you don’t even have to always know what the prayer means because the vibrations do produce a sort of, you know, element in you. You know, I’ll feel peaceful, I’ll feel strong, I’ll feel energetic with different prayers, and they are meant to evoke those things, and that’s what I find really special.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, that’s so interesting. I’ve heard that also of Muslims talking about Qur’anic Arabic. You know, but it’s a very foreign thing, particularly to Americans. We have our language and we translate everything into English. I think Sanskrit is the oldest language in the world.

MS. SHANKAR: It is. It is. It is.

MS. TIPPETT: But you also were raised in England and America. You know, how do you think about the way you relate to that ancient language?

MS. SHANKAR: Well, I — I don’t claim to know it at all. But you do feel it. I mean, in a way, I feel like English has too many words sometimes. I mean, I love it because it’s — it’s creative and you can really express your thoughts and your feelings. But I think not everything can really be explained in a mathematical way. You can’t always find the right word, and that’s what I remember from growing up because I did move away from the idea of I don’t want to just be praying all the time and I don’t know these words so it’s not relevant to me. And — and that was when I was probably a teen-ager. But you know, I just find that you — you don’t have to know. Like, you just say them again and again and it brings so much peace. It really, really does. It’s amazing.

[Excerpt from “Chants of India”]

MS. TIPPETT: And there’s also this primordial sacred sound, ohm.

MS. SHANKAR: Ohm. Absolutely.

MS. TIPPETT: Tell me about that. What does that mean for you?

MS. SHANKAR: Well, I mean, like you said, it’s — it’s the primordial sound. It’s supposed to contain, like, the whole power of the universe in that word. The three letters are ah, oo and mm. One thing I notice when people are chanting commonly, there’s a slight mispronunciation in the word because one of the deepest powers of that word is the vibration you get from the M sound. When — when you really hold your lips shut and — and say that, that — that produces a sort of vibration in your body. And most people tend to chant with this big, like, `Ohhh,’ and then just shut their mouth on the M for a second. But it’s really supposed to be, like, `Ohmmmmm,’ and that’s supposed to get louder for as long as — as long as you can hold that breath and it increases your breath control, your lungs get cleaned by it, and it’s supposed to have a really great spiritual effect.

MS. TIPPETT: And I notice on the “Chants of India” CD, I think, these prayers tend to begin and end with `ohm.’ Is that right?

MS. SHANKAR: Right.

MS. TIPPETT: Is that true of all Hindu prayers?

MS. SHANKAR: Almost always. It may not be written in the prayer all the time, but it is how people tend to start and end very often with `Ohm’ and then the word `shanti’ three times, which means peace, and then that’s a very common way of ending as well.

[Excerpt from “Chants of India”]

MS. TIPPETT: Anoushka Shankar’s latest CD is “Anourag.” I’m Krista Tippett and this is Speaking of Faith, on “Patterns of Prayer.”

[Excerpt from “Sim Sholom”]

MS. TIPPETT: This is “Sim Sholom,” a Jewish prayer for peace sung by tenor Richard Tucker. The Hebrew word for prayer means to be self-judging or introspective. On high holy days especially, Hebrew prayer texts urge the faithful to engage in self-examination, to fearlessly assess how they are living their lives. And the Psalms are the prayer book of the Hebrew Bible, used by Jews and also Christians. The Psalms invite the full range of human emotion into the presence of God, from celebration to envy to rage.

[Excerpt from “Sim Sholom”]

MS. TIPPETT: Here is a free translation or improvisation of Psalm 93 written and read by Stephen Mitchell.

STEPHEN MITCHELL: God acts within every moment and creates the world with each breath. He speaks from the center of the universe in the silence beyond all thought. Mightier than the crash of a thunderstorm, mightier than the roar of the sea is God’s voice silently speaking in the depths of the listening heart.

MS. TIPPETT: Stephen Mitchell is Jewish, and he spent the past two decades immersing himself in some of the world’s great spiritual texts — from the book of Job to the poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke; from the Hindu epic the Bhagavad Gita to the Tao te Ching.

MR. MITCHELL: My desire has been to enter a state of intimacy with them, so I spent six months or a year or 17 years, as with the book of Job, you know, their fingers pointing at the moon in an old Buddhist metaphor. It’s the words and it’s what shines through the words that I really care about.

MS. TIPPETT: Many readers share Stephen Mitchell’s passion. They spent over $2 billion on books with religious and spiritual themes last year, and his translations are popular among them. Stephen Mitchell insists that prayer does not need to be religious. Yet his understanding of prayer closely echoes many themes of traditional religion: gratitude, humility and transcendence.

MR. MITCHELL: Well, what I knew when I was a child was — was something very unattractive. It was — it was rote, it had nothing to do with the heart. It was a congregational kind of drone. Later, when I began to experience the texts of Hinduism — I guess that was what came first, the Bhagavad Gita and the Upanishads — my whole sense of God blew to smithereens. There was something much vaster than what I had thought that I was praying to.

MS. TIPPETT: I was interested when I looked at your anthology of sacred prose, “The Enlightened Mind”…

MR. MITCHELL: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: …that the — that the very final words are of the French philosopher Simone Veil…

MR. MITCHELL: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: …and she wrote, `Absolutely unmixed attention is prayer.’

MR. MITCHELL: I love that. I think that could be as close as someone can get to a wonderful definition of prayer. In that sense, prayer has nothing spiritual or religious about it. A mathematician working at a problem or a little kid trying to pick out scales on the piano is a person at prayer. She’s not saying prayer is absolute unmixed attention; it’s the other way. The attention itself is the quality that she wants to call prayer. So whatever context you’re putting it in, whether it’s inside a church or inside a toy box, that’s the quality that is the sacred one. Unidentified Reader: From Rainer Maria Rilke’s “Book of Hours.” Only in our doing can we grasp you. Only with our hands can we illumine you. The mind is but a visitor. It thinks us out of our world. Each mind fabricates itself. We sense its limits, for we have made them, and just when we would flee them you come and make of yourself an offering. I don’t want to think a place for you. Speak to me from everywhere. Your gospel can be comprehended without looking for its source. When I go towards you, it is with my whole life.

MR. MITCHELL: Rilke was writing from a depth of experience that communicates something to people, to a lot of people who don’t feel open to, quote, unquote, “religious texts” or spiritual texts. It’s much more a sense of praise, and you could say praise is another mode of prayer. It doesn’t have to do with longing; it has to do with concentration in the present and appreciation of everything in the present from a piece of fruit to a horse in the meadow to a human being. In this larger sense of prayer, there don’t have to be words to it. There can — it can be just everything; everything that you do from moment to moment is an expression of your gratitude.

MS. TIPPETT: I just want to say, you know, a sort of irony that strikes me. You have worked so intensively with words, but I sense that your real passion is — is for experience and that the traditions that you’re most drawn to maybe personally have more to do with silence. Is that — is that fair?

MR. MITCHELL: Well, from the beginning I think that’s what — that’s where you end up in the book of Job — in this vast open-hearted silence. And I think that’s where all — all of the most profound and beautiful words lead.

[Excerpt from “Sanya”]

MR. MITCHELL: This is a glimpse at not only a certain kind of meditative state but a certain way of living life that is what we might call a life of prayer in the Western tradition. So this is Chapter 16 from my version of the Tao te Ching: Empty your mind of all thoughts. Let your heart be at peace. Watch the turmoil of beings, but contemplate their return. Each separate being in the universe returns to the common source. Returning to the source is serenity. If you don’t realize the source, you stumble in confusion and sorrow. When you realize where you come from you naturally become tolerant, disinterested, amused, kind-hearted as a grandmother, dignified as a king. Immersed in the wonder of the Tao, you can deal with whatever life brings you. And when death comes, you are ready.

[Excerpt from “Sanya”]

MS. TIPPETT: Stephen Mitchell is the author of many books of translation, fiction and non-fiction.

[Excerpt from “Pilgrim’s Hymn”]

MS. TIPPETT: This is the music of Stephen Paulus called the “Pilgrim’s Hymn.” Though it was written only a few years ago, it’s become something of a greatest hit for the composer, already selling tens of thousands of sheet music copies to choirs around the world. Its text is a prayer written by poet Michael Dennis Browne.

[Excerpt from “Pilgrim’s Hymn”]

MS. TIPPETT: To end this hour, here is Michael Dennis Browne on his experience of the nature of prayer. A lifelong Catholic, he has in recent years embraced what is called Centering Prayer. It follows the example of the earliest Christian monastics who sought less to talk to God and more to listen and learn, to simply be in the presence of God. Michael Dennis Browne.

MICHAEL DENNIS BROWNE: I pray to open my heart. I do this not out of some ideal condition of spiritual confidence, but from out of the current mess of my own humanness — all my confusions, doubts, distractions, lack of courage. My sister Angela died in June of last year. In the months since then, I’ve felt myself swayed by huge gusts of sadness, soaked by cold rains of grief. My habit of prayer has saved me, helped me to keep my sanity, if you will. Angela was a woman of great faith with a radiant prayer life. When I’m able to pray, I feel very close to my beloved sister. I certainly have never believed I have lost her. In a typical day of my life, if things go right, there are layers of prayers. First, early, usually before first light, I begin with Centering Prayer, sitting on a prayer bench at the foot of the bed, some reading of Scripture, lectio divina, followed by 20 minutes of silence. The basic idea of Centering Prayer is to say, `Here I am,’ to invite the divine presence. It is helpful to have a sacred word to return to when the mind begins to wander, as it inevitably will, a word such as Abba or Father or Mother or love. But the word is not used as a mantra, and the aim is to let go and to be in a place of peace beyond all concepts and signs and words, a windless deep state of resting in God. I listen to a God I believe to be nearer to me than I am to myself, who is in me like a ground and a sky. Why do I pray? Because I adore and must express and receive this love. And I think of my ancestors who prayed, all who went before and all who pray now — sisters, brothers, all faiths, all paths — the waves of the faithful. I pray for a wider, deeper life in which I might have the courage and imagination to attempt larger things. I pray to be changed, to say thank you for the utterly mysterious gift of life, for the huge poem of the world. I pray to say yes.

MS. TIPPETT: Michael Dennis Browne is the author of several collections of poetry, including You Won’t Remember This and Smoke from the Fires.

We’d love to hear your thoughts on today’s program. Please send us an e-mail at [email protected]. You can also contact us through our website, speakingoffaith.org. While you’re there, you can listen to this program and more. You’ll find extensive book and music lists, other writings on prayer, and an archive of our past programs. You can also call Minnesota Public Radio at 1 (800) 228-7123.

[Credits]

CHILD: Thank you, God, for the world so sweet. Thank you, God, for the food we eat. Thank you, God, for the birds that sing. Thank you, God, for everything. Amen.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.