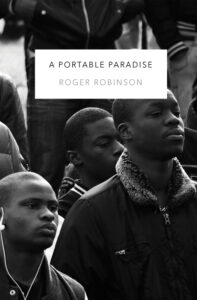

Roger Robinson

A Portable Paradise

How do you hold onto hope? And who helped you find it?

This poem is about holding onto paradise in the midst of an environment that seeks to steal or quash it. Roger Robinson praises his grandmother who told him to “carry it always / on my person, concealed.” His deft language helps us understand that paradise is a quality of life; and, even deeper than that, paradise is your life.

Image by Expedition Press/Expedition Press, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

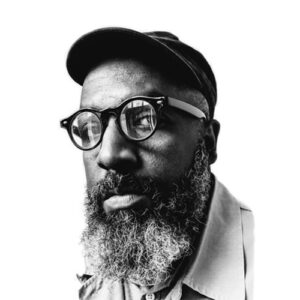

Roger Robinson is a writer and performer who lives between London and Trinidad. His first full poetry collection, The Butterfly Hotel, was shortlisted for The OCM Bocas Poetry Prize, and his latest book is A Portable Paradise. He is a co-founder of both Spoke Lab and the international writing collective Malika’s Kitchen.

Transcript

Pádraig Ó Tuama, host: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and one of the things I love about poetry is summed up with a line from Emily Dickinson, who speaks of telling the truth, but telling it slant. And sometimes a poet, if they want to make a serious point about politics, will enter into that serious point through the side door, and they might describe something of landscape or something of memory or something of joy, but there’s a line in it that strikes home, because that line is telling a deep political truth around which everything else gathers.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: Pádraig Ó Tuama: “A Portable Paradise” by Roger Robinson:

“And if I speak of Paradise,

then I’m speaking of my grandmother

who told me to carry it always

on my person, concealed, so

no one else would know but me.

That way they can’t steal it, she’d say.

And if life puts you under pressure,

trace its ridges in your pocket,

smell its piney scent on your handkerchief,

hum its anthem under your breath.

And if your stresses are sustained and daily,

get yourself to an empty room – be it hotel,

hostel or hovel – find a lamp

and empty your paradise onto a desk:

your white sands, green hills and fresh fish.

Shine the lamp on it like the fresh hope

of morning, and keep staring at it till you sleep.”

[music: “Memoriam” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: This is the title poem of a book by Roger Robinson, A Portable Paradise. He’s a Trinidadian poet who lives between Trinidad and London. And so his book pays attention to Trinidad, which is always with him, but as well as being black British. The book is a phenomenally contemporary one, honoring the struggle to survive in the face of institutional racism and classism in Britain. And it’s a book that honors family with tenderness and a book about art and the importance and value of art. And there is reference to place, place as a great nurturer, as well as, then, place as a place of threat. And I loved that this final poem, the title poem, seems to gather all of those themes together.

The book is a long reflection on paradise. And the word is such an interesting word, “paradise.” It comes into Latin and Greek, and English, through an early Iranian language, Avestan, which is the language of the scriptures, of Zoroastrianism. And it means “an enclosed garden”. And so, I suppose often, in English, you think of paradise, speaking of the garden of paradise, Eden. And John Milton’s epic poem called Paradise Lost is about Adam and Eve losing, or being expelled from, Eden. Or people might think about paradise as heaven, as well.

But Roger Robinson’s paradise is one that’s firmly located in the here and now. It’s located in the shell in your pocket or in the piney scent in your handkerchief or the anthem you hold in your ears. It’s not about a hereafter, it’s about a here. And I think that is part of the political protest of it, because in the here that the speaker of the poem lives in, there are people who want to steal your paradise. They can’t steal it, the grandmother is hoping, but they want to. And clearly, in this poem, there are wounds and sustained wounds and injuries and deaths that can come from your paradise being stolen.

I see the word “concealed” there, and I think of headlines where, in London, there might be references to young people of color carrying a concealed weapon. And I think he is deliberately taking this idea of concealed and talking about what do you conceal because other people will deny it and threaten you, other powers will, and people who say that they’re the law-keepers and threaten you with being perceived as the law-breaker. And I think, ultimately, he’s saying that your paradise is a quality of life; but, deeper than that, it’s your life.

[music: “Cirrus” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Ó Tuama: The elegance of this poem flows like music. And this poem has such extraordinary technique in it. And you can analyze the technique between the pronouns in it. There’s the line — the sixth line; it’s only a 17-line poem — the line “That way they can’t steal it, she’d say” — that’s a turning point in this poem, it’s a hinge, because before that line, you hear references to “I” and “me,” “if I speak,” “I’m speaking,” “told me,” “my person.” And then, after the sixth line, you see all these references to you: “if life puts you,” “your pocket,” “your handkerchief,” “your breath,” “your stresses,” “get yourself,” “your white sands,” “you sleep.” So the line, “That way they can’t steal it, she’d say,” is a hinge. And this hinge calls for our attention, because before it, you hear “I” twice and “me” twice, and after it, you hear “you” or “your” nine times. And so it really focuses us on that hinge line that calls for attention to wonder, who is the they that wants to steal it?

This poem isn’t sentimental. This poem is saying, here is what it’s like to hold a paradise, when you know you live in a reality that people would want to steal your paradise, steal your life.

[music: “What Did You Not Hear” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: One of the complexities of literature is the way within which literature invites people to identify with a point of view and with a character in it. And it’s so easy to want to be brought into the point of view of the speaker here, or the grandmother. And I think that there is always a literary and moral and ethical challenge, certainly, for me, is to find myself in at that line, “That way they can’t steal it, she’d say.” When have I been the “they”? When have I looked on somebody else and thought, “Oh, I want that,” and I might have denied that I’m stealing it, but I’m stealing it anyway. And so the literary invitation for me is to think about that line and how that line has impacted me, and how I have been the demonstration of the impact of that line.

And after that, then, maybe, after I’ve done some of that work, I can think about, oh, how do I identify with the poet? How do I identify with the grandmother? Who has been that for me? Where are the places that sustain me and keep me going in my mind? But that part there is the immediate and primal challenge to me, and I think that’s an important thing, in terms of the ethics of reading.

[music: “The House You Wake In” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: I think this poem invites people who have lived under a sustained threat to imagine what has sustained them through living through that threat and whose voices in their ancestors and their matriarchs have given them ways to hold onto something that keeps them alive, as well as then maintain the focus to know that it isn’t your fault, that there is something out to steal, there is a “they” out to steal what’s going on; and from that, then, to keep that in your mind, too — to be aware that you’re in the struggle. And I think, other people who haven’t lived under sustained torture and sustained stealing, and people who have lived in systems that have benefited them, rather than bereaved them, I think the invitation here is to pay attention to, when have I been the person who, whether I admit it or not, has been out to steal the paradises that keep people alive?

Ó Tuama: “A Portable Paradise” by Roger Robinson:

“And if I speak of Paradise,

then I’m speaking of my grandmother

who told me to carry it always

on my person, concealed, so

no one else would know but me.

That way they can’t steal it, she’d say.

And if life puts you under pressure,

trace its ridges in your pocket,

smell its piney scent on your handkerchief,

hum its anthem under your breath.

And if your stresses are sustained and daily,

get yourself to an empty room – be it hotel,

hostel or hovel – find a lamp

and empty your paradise onto a desk:

your white sands, green hills and fresh fish.

Shine the lamp on it like the fresh hope

of morning, and keep staring at it till you sleep.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Lily Percy: “A Portable Paradise” comes from Roger Robinson’s book of the same name. Thank you to Peepal Tree Press who gave us permission to use Roger’s poem. Read it on our website at onbeing.org.

Poetry Unbound is Chris Heagle, Erin Colasacco, Serri Graslie, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Christiane Wartell, Karen Navarre, Karyn Towey, Sue Ariza, and me, Lily Percy. Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions. This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. We also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me — find those wherever you like to listen or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.