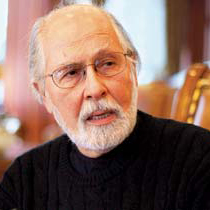

Seyyed Hossein Nasr

Hearing Muslim Voices Since 9/11

Dramatic headlines convey a predominantly violent picture of global Islam. But, during the past five years, Muslim guests on SOF have conveyed a thoughtful, questing, diverse, and compelling faith. Step back with us and hear these voices from the traditional and evolving center of Islam. And, Krista speaks with Seyyed Hossein Nasr, an esteemed Muslim scholar who brings a broad religious and historical perspective to hard questions about Islam and the West that have lingered uncomfortably in American life since 9/11.

Image by Murat Tellioglu / EyeEm/Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Seyyed Hossein Nasr is University Professor of Islamic Studies at George Washington University. He's a prominent philosopher and scholar of Islam who has written many books, including The Heart of Islam and Man and Nature.

Transcript

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett. Dramatic headlines convey a predominantly violent picture of global Islam. This hour, we’ll hear voices from the traditional and evolving center of this faith since 9/11, and I’ll speak with esteemed Muslim scholar Seyyed Hossein Nasr. He brings a broad religious and historical perspective to hard questions about Islam and the West that have lingered uncomfortably in American life these past five years.

MR. SEYYED HOSSEIN NASR: All this talk of clash of civilizations is very unfortunate. There are civilizations, with an “s” — yes. Not one civilization is going to dominate the whole world. I believe in the deepest sense that the destiny of Islam and the West is intertwined, not opposed to each other.

MS. TIPPETT: This is Speaking of Faith. Stay with us.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett. Islam is the second-largest religion in the world, and the faith of over 1.2 billion people. But until September 11th, 2001, Islam did not figure largely in the imagination or education of Americans. What has U.S. culture learned about global Islam in the intervening five years, and what do we still fail to hear and see? This hour, we’ll explore the evolving and traditional center of Islam.

From American Public Media, this is Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas. Today, “Hearing Muslim Voices Since 9/11.”

If 9/11 hadn’t happened, I suspect that I would not have spent so much time these last five years in conversation with Muslims. My conversation partners have been Asian, Arab, African, and North American by origin. Islam is an astonishingly plural, inclusive faith in the broad sweep of its history and its theology. That history and that theology were overshadowed on September 11th, 2001, by unforgettable images of airplanes crashing into buildings. They continue to be overshadowed today by other bombings and insurgencies.

The Muslims with whom I’ve spoken insist on an honest appraisal of the destructive energies alive in their faith. But they long for a nuanced appraisal, too — informed and intelligent enough to unravel extremism from devotion to distinguish between what is ideological and what is religious.

MR. OMID SAFI: You still hear from a lot of people, why aren’t the moderate Muslims speaking out? And, you know, at some level, you just — you feel like, you know, I’ve lost my voice from speaking out.

MS. LEILA AHMED (FROM “MUSLIM WOMEN AND OTHER MISUNDERSTANDINGS”): I get constantly called and asked to explain why Islam oppresses women. I have never yet been asked, why is it that Islam has produced seven women prime ministers or heads of state, and Europe only two or three or whatever it is?

MR. VINCENT CORNELL (FROM “VIOLENCE AND CRISIS IN ISLAM”): We’re faced with this crisis where we have now become the problem, you know, capital T, capital P. The microscope is focused on us, and we are now forced to take stock of what we as a community have done to ourselves.

MS. TIPPETT: We’ll revisit these and other Muslim voices throughout this hour. And with my guest, Seyyed Hossein Nasr, we’ll approach hard questions about Islam and the West that have lingered uncomfortably in American life these past five years. A professor of Islamic Studies at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., Nasr is a foremost global scholar of Islam. Born into a distinguished family in Iran, he studied physics as well as Eastern and Western philosophy at Harvard and MIT. He became one of Iran’s leading scholars until that country’s Islamic revolution in 1979.

Seyyed Hossein Nasr does not believe in an inevitable clash of civilizations between Islam and the West. This idea has been put forward primarily by non-Muslim Western thinkers. But Nasr does believe, provocatively, that the future of the West will depend on its willingness to see its own complicity in the historical circumstances from which extremist Islam has emerged.

On September 11th, 2001, Seyyed Hossein Nasr was in Cairo.

MR. NASR: That afternoon, Cairo time, I was at the Hilton Hotel, which is just a few yards up from my hotel, in the coffee shop downstairs, writing something. And I looked at my watch, it was about 4:00. I said, I better go to my room and say my afternoon prayers. So I came back to my room and I turned on CNN to see briefly what the news was, and I saw this image of a plane going into a building. I thought it was an advertisement for some kind of a horror movie or something like that. So I turned on Al-Jazeera and again, the same thing. I said, oh, my God. There must have been a great tragedy. And immediately I called a friend and I said I want to go to the center of Cairo, to Al-Azhar University and the bazaar to see what is going on — what the reaction is in this, one of the greatest of Islamic cities, what the impact of this news would be on the people.

MS. TIPPETT: Can you tell me a little bit about what you heard that day in Cairo?

MR. NASR: Yes. In contrast to all the images that were shown on American television, of people dancing in the street, there was, in fact, a great deal of shock. They couldn’t believe it. They were all saddened. And what I heard a lot was recitations of the Qur’an at times of great tragedy, versus of the Qur’an like subhan Allah — “praise be unto God” — which we use when we see strange and powerful and fearful things, and a lot of phrases like that being used by shopkeepers and the like, everybody standing and waiting to see what would happen next. That’s what I saw.

MS. TIPPETT: So much has happened since that day. And you know and I know that Islam — as you say, it’s not just a religion but a civilization, and had been profoundly important for so many people in the world for so many centuries. But it was on that day that Islam kind of came into view for many people in this country. If you could go back to September 12th and begin the conversation about what you would like Americans, Westerners, to understand about Islam — with these pictures in mind and despite these pictures of the airplanes crashing into a building — you know, where would you want to start the conversation?

MR. NASR: I would like to start the conversation with two points. First of all, why was it that there was such ignorance about Islam before this event? Secondly, the first logical question that should have been asked is why did this happen? And for about two or three weeks, this question was asked, and then the window of opportunity was closed. Why should such an event take place? Why should young men put their lives on the line to do this horrendous and terrible act, which they did?

MS. TIPPETT: Well, tell me where would you begin to answer that? Where do you want to begin talking about that and explaining it?

MR. NASR: Every effect has a cause, otherwise we could not speak logically together. And so the first thing we must ask is this event — which is based on such hatred that it makes people lose their lives and also kill innocent people in the process — why is there such anger? Why is there such hatred?

MS. TIPPETT: In these young men.

MR. NASR: In these young men who did such a thing. Then, when we analyze that, we realize that has a lot to do with the relationship between the West and the Islamic world. Putting the colonial experience aside — which Muslims shared with Hindus and Buddhists and African native people and everybody else — the presence of oil, which has caused many, many governments to be created in the Middle East, which are distained by their people, which are kept in power by the West because of the trust they have that they’ll keep the oil flowing and things quiet and the Arab-Israeli conflict — which has bled the region for 60 years without there being any solution — are the two main causes of great anger against the West.

MS. TIPPETT: You have a broad perspective, a longer historical view from your own life, from your scholarship. But you’ve lived in this country long enough to know that that kind of long historical view is very alien in this culture.

MR. NASR: That’s right. It isn’t that there is no sense of historical reality, but there’s no sense of historical reality when it comes to anything outside of the Western experience. Now, America is not only a player, but the major player upon the global scene. I’ve said always — half-jokingly but half seriously — that ignorance is bad. But worse than ignorance is applied ignorance. You know, we talk about science and applied science. I mean, if Brazilians have no historical sense, they do not understand Islamic world, do not understand Asia, so what? It’s just a shortcoming in their educational system. Let’s hope in the future they will learn. But America affects the life of those areas about which it is ignorant.

MS. TIPPETT: But I would even say that actions of extremist Muslims also manipulate that ignorance in a way that’s destructive all around. Do you know what I’m saying?

MR. NASR: Absolutely.

MS. TIPPETT: Create reactions. And that’s part of the terrible spiral we’re in now.

MR. NASR: In the Islamic world itself, those people who are extremists also try to manipulate the faith of young people combined with anger. But there is not an equality, that’s what’s important.

MS. TIPPETT: What do you mean by that?

MR. NASR: Economically, militarily, politically — there’s no equality. The impact of American pop culture upon Islamic world is not equal to the impact of Muslim culture upon America. The influence of the West on Egypt is not equal to the influence of Egypt on the West. The interests of the West in the Persian Gulf is not equal to the interest of Iran in the Gulf of Mexico. So when in one sentence one puts one tremendous power on one side, on the other a much weaker but insidious power on the other side, one is forgetting that the more powerful side has a lot more means of doing things. Unfortunately, the powerful side has chosen only the path of force, of military power, and that’s the one level in which the weaker power can manipulate through guerrilla warfare, through terrorist action, and so forth and so on, to half paralyze the much more powerful civilization.

MS. TIPPETT: Muslim scholar Seyyed Hossein Nasr. In order to understand the anger of young Muslim suicide bombers, I spoke in early 2002 with Khaled Abou El Fadl. He’s a professor of law at UCLA and a global human rights activist. But he had a narrow escape from Islamic fundamentalism as a teenager growing up in Egypt. Here’s an excerpt of our conversation.

MR. KHALED ABOU EL FADL: As an Egyptian, it becomes very concrete when you think everywhere you turn, the identity to which you belong is confronted with military defeats. If you carry an Egyptian passport and you try to travel around the world, you’ve become thrown into a category of the inferior just by virtue of the fact that you belong to an Arab identity. And I remember, you know, going through a stage where I tried the sort of cool route of being Westernized. That, for me, didn’t work.

And what did work was that exaltation, intoxication, remarkable high of finding a group of people that tell you, ‘You know what? You’re better than the Americans. You’re better than the British. You’re better than the Arabs. You’re better than anyone because you’re Muslim. And all you have to do is just simply accept our version of orthodoxy.’ And I remember as a teenager, suddenly, I would walk around with my head high and I could see the world as black and white, evil and good, and I was on the side — in fact, not just on the side of good. Anyone who wants to achieve goodness has to come through me. Fortunately, I grew out of it. Unfortunately, many of these kids never get that chance.

MS. TIPPETT: Khaled Abou El Fadl from our program, “The Power of Fundamentalism.” You can hear that interview and others in full on our Web site at speakingoffaith.org. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, “Hearing Muslim Voices Since 9/11.”

Now back to my conversation with Islamic scholar Seyyed Hossein Nasr.

MS. TIPPETT: I want to ask you one of the other hard questions that’s raised, and this is a hard question spiritually as well as politically. When you say we have to understand what makes these people so angry that they become terrorists, that they kill others — a reaction in this culture is you’re excusing violence. At the point at which a person has taken another person’s life, there’s no longer any excuse. A lot of people suffer, but they have crossed a line beyond which that question of what made them do it is still no response to what they did.

MR. NASR: Those who have crossed the line, there’s no excuse for them. There’s no way to excuse them. The reason we’re discussing this is to prevent other people from crossing the line. When the African-American community burned Washington, D.C., in the ’60s, that had crossed the line. They burned half of Foggy Bottom, where my office is. People didn’t say, well, they’ve crossed the line. We don’t want to understand what the cause for this was. If they had said that, there would have been no civil rights reforms. Whites who were intelligent, who didn’t want to have this happen to the country, they said, ‘Let’s find out why it is that these African-Americans are so angry that they’re burning Foggy Bottom.’

MS. TIPPETT: So that this doesn’t continue to happen again and again.

MR. NASR: Exactly. This is not those people who actually were carrying torches on 22nd Street and burning townhouses. Their violence can’t be condoned. No. That’s a criminal act. But one has to try to understand what the cause is so that this will not be repeated in the future. At least, it will become less so.

MS. TIPPETT: Since September 11th, 2001, Americans have seen fundamentalist Islam, and there’s been this sentiment, this cry, that I’ve heard, I’m sure you’ve heard many people say in our culture: ‘Where are the moderate Muslims? Where’s the center? Where’s the moderate voice?’ And the point that you make is that we are not looking in the right place for the Islamic center. That we are looking, in fact — with our history of separation of church and state as it developed in the 20th century — for a secular moderate voice. And the point that you want to make is that, in fact, that’s the other extreme and that we have to think completely differently about what the Islamic center is. So talk to me about that.

MR. NASR: It’s very important to understand that moderate Islam, as you just said, does not mean secular Islam — which is a contradiction, it’s even an oxymoron — but secular Muslims. The experience of secularism in the West is unique to Western civilization. And even in the West, there’s a big difference between the Queen of England being the head of the Anglican church and in America where they talk about the separation of church and state. And even that separation is very different from the 19th century. Otherwise, why do you have on your coins “In God We Trust”?

Now, there is the tendency in America to want to convert the world to our view — and not our long-term view, our view of the immediate moment, the absolutization of the transient. We have the tendency in this country to absolutize very, very transient fashions and ideas and so forth at the moment when we’re living it. And that’s why, today — I always said the 1950s is like pharaonic Egypt: it’s already long, long time past. Whereas many people are alive today were alive in 1950 and functioning. And so we want to convert the world not to what, let’s say, Andrew Jackson thought or Abraham Lincoln thought, or even Thomas Jefferson or Alexander Hamilton, but to what we consider right now.

MS. TIPPETT: About the interaction between religion and public life, which is very…

MR. NASR: Exactly.

MS. TIPPETT: …different from what we think now, yeah.

MR. NASR: Absolutely. Absolutely. And the Muslims and, in fact, all Asians say, what guarantee do we have that in 2100 you will not be thinking of something else? Christianity resisted becoming simply a Sunday-morning phenomenon for many, many centuries — from the 1500, let’s say, during the Renaissance, until the 20th century. And we expect the Muslims to jump from, let’s say, Dante to Karl Marx, and then to President Bush in a five-year period. I mean, that’s not going to happen.

MS. TIPPETT: Right. Talk to me though about what that Islamic center looks like. You make an intriguing analogy in one of your books. You say, you know, it doesn’t mean Muslims who are not religious. And, for example, in some ways the way people in the West have come to hear Muslims — you know, the minute there is this very religious view of life, that is suspect. You know, that’s perhaps veering towards this Islamic fundamentalism that is the great problem. But you say there’s a figure like, say, Mother Teresa, right…

MR. NASR: Exactly.

MS. TIPPETT: …who is not a religious fundamentalist, she is a faithful person, and that even in the Christian world — in a Christian worldview — there’s a place for people like that who are passionate about their faith and not frightening. When you say most Muslims in the world are in that center, are moderate, describe them to me. You know, what does that mean? How are they Muslim?

MR. NASR: Certainly. First of all, I usually use the term traditional Islam and distinguish it very clearly from both modernism and secularism on the one hand, and fundamentalism or Islamism or we like to it on the other hand.

MS. TIPPETT: So one end of extremism is religious fundamentalism or extremism.

MR. NASR: That’s right. The other extreme is secularism and modernism, and the two are the two sides of the same coin.

MS. TIPPETT: They can both be fundamentalist.

MR. NASR: Not only they can both be fundamentalists, but on many things they have the same view. For example, lack of interest in traditional sacred art, complete espousal of modern technology with total lack of regard for the environment. Many things which are fundamental to contemporary life, they share together. It’s very interesting. Have you ever heard a doctrine or secularist say, ‘All right, secularism is one point of view. Religion is another point of view. They both might be right in their own way, and let’s live together’?

MS. TIPPETT: So you’re saying it’s dismissive and intolerant of any kind of religious worldview, in the same way that a religious fundamentalist is dismissive and intolerant of a secular worldview.

MR. NASR: That’s right. Exactly. And modernism also has to limit its own claims. I accept that this is one way of looking at the world, but there are other ways of looking at the world. I’m not dismissing those as being for simpletons.

MS. TIPPETT: Iranian-American scholar Seyyed Hossein Nasr. Here’s an excerpt of a conversation with a young Iranian-American scholar, Omid Safi. He’s a leading voice in a new movement called Progressive Islam, and he also sees religious fundamentalism and secular modernity as the two extreme poles of Muslim life.

MR. OMID SAFI: If you go back 50 years and you listen to what the liberal Muslims were saying, essentially it was, you know, we want to be as Western as possible, as modernized as possible, as scientific, rational, technological as possible because that’s what the Europeans are like. And I think what has happened with this emergence of the group that we’re calling Progressive Muslims is that we are exposing modernity to the same kind of critique that we are doing to our own tradition.

It’s to say that there are incredibly powerful and profound things that take place in modernity such as, you know, the rise of scientific development and notions of democracy and human rights, but that these same developments also have a very dark and nasty underbelly. And I think that, you know, the absolute environmental destruction that we have inflicted upon the world in a way that has never existed before, the legacy of colonialism — I mean, what is, after all, 19th century and, you know, much of 20th century about other than colonizing 85 percent of the world?

So modernity cannot, for us, be this entirely wholesome package that we must somehow download. And it’s that sense of grudgingly engaging both our own tradition and modernity to find the best elements of both that I think is new.

MS. TIPPETT: Omid Safi of Colgate University. I spoke with him in 2003. This is Speaking of Faith. On our Web site, hear all of my interviews with Muslim guests from the past five years and read reflections on Islam since 9/11 from some of our Muslim listeners. Also, each week I provide a behind-the-scenes look at the topic explored. You can sign up for our e-mail newsletter at speakingoffaith.org.

After a short break, more from my guest Seyyed Hossein Nasr and others. Where should non-Muslims look to find images powerful enough to counter the indelible pictures of Islamic extremism from 9/11 and beyond?

I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us. Speaking of Faith comes to you from American Public Media.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics, and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today, an exploration of the roots and contours of the post-9/11 world with Muslim voices.

If I’ve learned anything these past five years from my conversations with Muslims, it is this: Islam is a faith of daily-lived piety. Traditional Muslims define their lives of faith more in terms of being and doing than in articulating beliefs and doctrine. There is in Islam no sense of separation between the sacred and the secular. This very idea alarms U.S. instincts about separation of church and state. But here’s an American description of this virtue by Chaplain Major Abdul-Rasheed Muhammad. He is African-American, like one-third of U.S. Muslims. He converted to Islam from Christianity as a young man and later became the first Muslim chaplain in the U.S. Army. I interviewed him in 2005 after he returned from active duty in Iraq.

CHAPLAIN MAJOR ABDUL-RASHEED MUHAMMAD: There is no real separation between the practice and the beliefs, and the beliefs basically are five basic principles. That’s where it all starts from, you know, a belief in one God, Muhammad being his last prophet. Prayer five times a day. The institution of charity, or Zakat, which is a annual payment or also a regular series of charity or charitable kinds of actions. Fasting in the month of Ramadan once a year for 29 or 30 days. And making the pilgrimage to Mecca once in a lifetime. Those are the five basic tenets of the religion.

What I would really personally like to see more of is talking more to people in this country who are taxpaying citizens, who pray five times a day, who are part of organizations, many of whom are professionals. I mean, we’re not hearing a whole lot from them, but we seem to have this tendency to want to almost associate Islam with people who are extreme in their views. And I don’t quite understand that.

MS. TIPPETT: Chaplain Major Abdul-Rasheed Muhammad from our program, “Serving Country, Serving Allah.”

As my guest Seyyed Hossein Nasr has been describing, he sees the roots of present misunderstandings in the past few centuries of modern history. Sharia, or Islamic law, is a formal expression of Islamic piety woven into the fabric of daily life and society. Sharia’s traditional diversity of forms was obscured during several hundred years of Western colonialism. This affected most Muslim cultures around the world, and only finally ended in the latter half of the 20th century.

MR. NASR: There’s a great deal of tension that has been created by the fact that traditional Muslims — I don’t mean extremists, I don’t mean people who have recourse to violence, but people who live as Americans used to live in New England in 1800, as Catholics lived in the 18th century, going to mass three times a day — in fact, up to the 20th century. The Muslims want to be able to live that normal life they had always led.

MS. TIPPETT: But as you know — I mean, I do think that the term sharia law has become inflammatory as much because of the way it’s been used by Muslims, by some Muslims, as by the fact that Western non-Muslims haven’t had a context to understand its original meaning.

MR. NASR: You know, if the Muslims had been left alone — there’s a saying in English, ‘Give him enough rope to hang himself,’ even — they had been left alone to let the inner dynamics of various Islamic societies work itself out, whether people wanted to have the sharia or not, or this part of the sharia and not other part, to transform the sharia or not, and so forth and so on — we would not even be having these debates.

I’ve always said that the West had a tremendous advantage over the other civilizations of the world in that while it was undergoing those very profound and sometimes cataclysmic transformations from the guillotining of Louis XVI, before that the abduction of the Pope into Avignon, to the revolutions — American and French Revolutions, and the Russian Revolution — and the communes of Paris and Germany, and all of these very, very powerful social, philosophical, religious transformations, there was not another civilization hovering over its back and pressuring it from the outside. All the transformation in the West came from the inner dynamic of Western society.

Whereas today, no society in the world — perhaps with the possible exception of China, but even that isn’t total exception — can have that privilege, and that is the main problem, that it causes a kind of rising oppression, a pressure-cooker without any release.

If you left the Egyptian people alone, really alone to elect people, not to have the army hovering over it and supported, of course, by Western powers which allow such a thing and so forth and so on, it would, in a few years, gradually work out a modus vivendi, which would not be as terrible as people in the West think. Whereas, in fact, by not leaving it alone…

MS. TIPPETT: But it would be organic, it would…

MR. NASR: It would be organic, and it’s natural for human beings to want to be happy, to be at peace, to be prosperous. I mean, no Muslim is any different from an American or a Swede in the basic human desires and needs. They’re human beings who want to have a family, who want to be able to live at peace and so forth and so on, and gradually things would work themselves out. But the reason you have so much tension is that you have pressure from an outside civilization in practically every domain of life of the Islamic world. And since Islamic civilization is not dead, it reacts.

And so what happens is that a number of misguided people who begin with a love for their faith end up in the hands of the devil, in a sense, of taking recourse to extreme action, doing things which are against Islamic law. For example, killing the innocent is specifically banned in the Qur’an. The Qur’an says to kill one innocent person is like killing the whole of humanity. It’s a hideous act. So to save the sharia, they’re going against the sharia.

MS. TIPPETT: Seyyed Hossein Nasr. In 2004, as Islamist violence intensified in Iraq and elsewhere, I spoke with Vincent Cornell, an American who converted to Islam 30 years ago and is now esteemed in global circles of Islamic scholarship. The Muslims who were responsible for 9/11 and who’ve propagated violence beyond it, Cornell says, practice a radically superficial version of that faith. He sees the present as a moment of ferment within Islam, very much like that which preceded and accompanied the Christian Reformation. But it’s happening in a borderless world of far more dangerous weapons.

MR. VINCENT CORNELL (FROM “VIOLENCE AND CRISIS IN ISLAM”): For myself, the Islam that I accepted through the Qur’an and through now over 30 years of study of classical Islamic works throughout Islamic history, is to a large extent not the Islam that I see on TV and being expressed by many people in the Muslim world. The desire for revenge, the desire for glory, the desire for personal heroism, the desire to eliminate all norms of decency and ethical behavior in the cause of a political goal, all of these things that are being expressed by Muslim extremists are specifically mentioned as aspects of pre-Islamic society that Islam came to end and eradicate. And so for Muslims like myself, what makes this particular time so painful is that everything is in a sense reversed. The world is upside down. You know, it’s a 180-degree reversal.

MS. TIPPETT: Vincent Cornell from our program, “Violence and Crisis in Islam.” Now back to my conversation with Seyyed Hossein Nasr. I asked for his perspective on the present politicized form of Islam in Iran, the country of his birth.

MS. TIPPETT: I do feel like, you know, these five years on, from September 11th, Iran appears as one of the pivots of whatever is going to happen, however this is going to go.

MR. NASR: That’s right.

MS. TIPPETT: Now, what would be your wisdom on that? Because I think Iran is suddenly very frightening to people in this country, and how would you want to speak to that?

MR. NASR: Let’s, first of all, talk about the facts. Iran is a country three times the size of France. It has over 70 million people, has a very large educated sector. It has oil. It has the second-greatest reserve of gas in the world, and it has very diverse climates and is a power — a local power. Even if the present government should change, it would still be a local power. It has to be taken into account. This is the first point.

Secondly, intellectually, Iran is one of the most exciting places in the Islamic world in that within the Islamic republic, there’s been so much translation of current Western thought and encounter with Western thought — whether it’s philosophical, theological, scientific, and so forth and so on down the road, and responses — and Iran will without doubt be one of the major centers of Islamic thought in the future. And it already is.

MS. TIPPETT: I want to say that that’s something that’s come through very clearly in my conversations of recent years, that to the extent there is an intellectual opening and reformation and important conversation happening within Islamic theology. It’s happening in Iran…

MR. NASR: That’s right, that’s right, more than any place else.

MS. TIPPETT: …but, you know, it’s hard to — you know, first of all, most people don’t know that. And it’s hard to reconcile that with the image that we now have of Iran as this country that is grabbing power and supporting Hezbollah. Right?

MR. NASR: Yes, we say it is…

MS. TIPPETT: Is it just that they’re both true at the same time?

MR. NASR: Well, it’s very easy to demonize someone, in the same way that Arab and Iranian stations demonize United States so easily. As to the future, the best way to face the future is to face reality. To face reality means that one has to talk with even a power that one doesn’t like. President Nixon went to talk to China. It didn’t mean that Americans loved China. China was a Communist country at that time, was killing millions of its own citizens, and it remains to this day a hundred times more dangerous than Iran.

But right now, the politics of the moment works in such a way that we refuse to talk to Iran. Iran holds so many cards in its hands which are vital for the United States, including the well being of Iraq. Iran has a thousand times more influence in Iraq than the United States does. And the best way to do it is for the United States to agree to talk to Iran. And, in fact, that would also soften many positions within Iran itself. Not all Iranians are happy about very hard-line positions, but the very policy that we’re using strengthens those people.

MS. TIPPETT: Muslim scholar Seyyed Hossein Nasr. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, an exploration of the post-9/11 world with Muslim voices.

One year after 9/11, I interviewed the Islamic educator Ingrid Mattson of Hartford Seminary. Shortly before 9/11, she became the first woman elected vice president of the Islamic Society of North America. As she watched those pictures on the television screen, she feared that all she had worked for had been lost. I asked Ingrid Mattson where she would have non-Muslims look for images dramatic enough to counter those pictures that associated Islam with airplanes crashing into buildings.

MS. INGRID MATTSON: Well, you’ve hit right on it. I mean, that’s the point, is that violent actions are much more dramatic and memorable. A Muslim who’s motivated by faith will sometimes in their life have an opportunity to do something, you know, grand, but most people don’t. Most people, they live out their faith day to day by small actions of generosity, humility, and gratefulness. I think what Americans need to do is look around them and see many hospitals, for example. That there are many Muslims doctors, and day after day they are serving people, they’re helping people. Certainly, it’s a result of their training, but it’s also an aspect of their faith. There are Muslims working in soup kitchens and in those shelters. So you won’t — you know, you don’t necessarily see that drama because it requires some kind of active outreach or at least a desire to look for those Muslims on the part of other Americans. But I believe that in the end it’s worth it.

MS. TIPPETT: On August 23rd of this year, Ingrid Mattson became the first woman president of the Islamic Society of North America. I posed the same question to Seyyed Hossein Nasr that I once posed to her: Where would he have non-Muslims look to balance the many images of extremist Islam that have continued to galvanize the world these past five years?

MR. NASR: First of all, you give me CNN for one week, and I’ll do it for you.

[Soundbite of laughter]

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

MR. NASR: Television can, in a sense, determine people’s view of almost anything. That’s why I said jokingly, give me CNN for one week and I’ll do it for you. But the images to look for is the orderly life of pious Muslims. They’re not secularists, but live a moral life, which I think many Christians would appreciate — very close to what Christians and Jews consider to be the moral life, whether sexual morality, personal morality, economic morality, and so forth and so on down the road.

And the rhythm of their life, what they do during their life, their interest in knowledge and schooling despite the poverty that exists in many places — and all one has to do is to take the camera from Senegal to Mauritania to Morocco, all the way across to Indonesia. And 95 percent of all those areas, you will see Muslims living ordinary human lives as servants of God, as pious people.

MS. TIPPETT: Whatever the reasons are, it’s clear that extremist Islam has gained in power, in visibility, in influence it seems, and that that is fueled by all kinds of other things that are happening in the world. Do you look around, have you watched what’s happened in the last five years and felt that Islam itself is changing? And that that center, that traditional Islam, is being eroded by all of this?

MR. NASR: Not very much. Much less than many people say. There are two different currents that are going on in the Islamic world, and they must not be confused one with the other. One is a traditional, normal desire of the majority of people to undo the effects of the colonial period upon their lives in many different modes, many different ways — from dress to economics, to art, to schooling, education, so forth and so on down the road. The other is this extremism, which is violent and which tries to recruit people from the first group, who are devout but who think they are not getting anywhere because their voice is not heard in their country.

Both of these currents are going on, and one must not be confused with the other. We always hear about the extremist minority. Let’s say we hear 20 young people among the Pakistanis in London compared to 1.9 million South Asians who live in London or close to that. That’s a pretty small number. Nobody pays attention to all the other young men. So yes, they’ve been successfully recruiting, but a very small number. So the most important phenomenon is the mainstream. And unfortunately, American sociological studies are based on the study of change and not permanence.

MS. TIPPETT: So the hope for you would be in focusing on that other 1.9 million.

MR. NASR: Absolutely. Not only that, but upon the 1,250,000,000 people of whom at most 30, 40 million, at most, have radical tendency. Much less than that, it’s not even 10 million. But supposing that you take the highest number, you still have the vast, vast majority of Muslims. Of course, some of them are secularized like in Turkey and in Tunisia, but they’re a very small number. They’re maybe a few million. The vast majority are traditional Muslims, and they have to get their act together to be able to present themselves to fight for the right values within their society.

But they cannot change their image on CNN. That is for America to do, to try — not to be prejudiced for Islam, but also not prejudiced against Islam. All this talk of clash of civilizations is very unfortunate. There are civilizations, with an “s” — yes. Not one civilization is going to dominate the whole world. We have to accept the plurality of civilizations, the religions, the arts, the culture which dominate and have, in a sense, been the drawing force of those civilizations. And we have to mutually respect each other. I believe in the deepest sense that the destiny of Islam and the West is intertwined, not opposed to each other.

MS. TIPPETT: Seyyed Hossein Nasr is University Professor of Islamic Studies at George Washington University. His books include Islam: Religion, History, and Civilizationand Knowledge and the Sacred.

Polls suggest that U.S. citizens have developed a progressively negative opinion of the religion of Islam in recent years. More than one in three Americans believe that Islam is more likely than other religions to encourage violence among its faithful. But the same polls suggest that knowledge of Islam and personal acquaintance with a Muslim have a power to temper this perception. We’ll continue to draw out the human faces and voices at the center of this global tradition in the months and years to come.

MS. SEEMI BUSHRA GHAZI (FROM “THE SPIRIT OF ISLAM):And I have to remind myself that the kind of work I do, teaching Arabic at the university or talking or just interacting on a daily level with people and having them have a different experience of Islamic tradition through me, that that subtle work will remain and will continue and will have power sort of beyond any kind of blunt instruments of terror that may seem to be destroying the bridges and closing the gaps where there’s communication.

MR. RAMI NASHASHIBI (FROM “THE PROBLEM OF EVIL”):(Passage from Qur’an spoken in Arabic) Have mercy on that which is on earth, so that which is in heaven can have mercy on you. The fact that that message has been unfortunately somewhat either minimized or cynically dismissed becomes very apparent in the harsh realities of our lives, whether they be in the inner cities, in the ghettoes of Chicago, or whether they be in the refugee camps of Muslims throughout the world, this aspect of our faith traditions, as a Muslim, I try to fall back on.

MS. LEILA AHMED (FROM “MUSLIM WOMEN AND OTHER MISUNDERSTANDINGS”): Yes, well, look it, for one thing, I no longer believe that there’s a Islamic world because where exactly are the borders? Are they in Chicago? Where are they? Where does the Islamic world and where does the West begin? Is it in Paris, or where is it? So I do think what happens in this country is going to be as much about the Islamic world as whatever happens over there. The Islamic world is no longer over there. That’s one thing. The other thing is I think what we do, what we Americans do, will profoundly determine what becomes of what we’re calling Islamic world.

MS. TIPPETT: Seemi Ghazi, Rami Nashashibi, and Leila Ahmed. At speakingoffaith.org, you’ll find all my conversations with Muslims from the past five years. They include programs on “The Spirit of Islam,” “The Power of Fundamentalism,” “Progressive Islam in America,” Muslim Women and Other Misunderstandings,” and “Violence and Crisis in Islam.” There you can also contact us with your thoughts and sign up for our free e-mail newsletter, which brings my journal on each week’s topic straight to your inbox. That’s speakingoffaith.org.

The senior producer of Speaking of Faith is Mitch Hanley, with producers Colleen Scheck and Jody Abramson and editor Ken Hom. Our Web producer is Trent Gilliss, with assistance from Jennifer Krause. Kate Moos is the managing producer of Speaking of Faith, the executive editor is Bill Buzenberg, and I’m Krista Tippett.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.