Sylvia Poggioli, Donald Cozzens, and Margaret Farley

The Religious Legacy of John Paul II

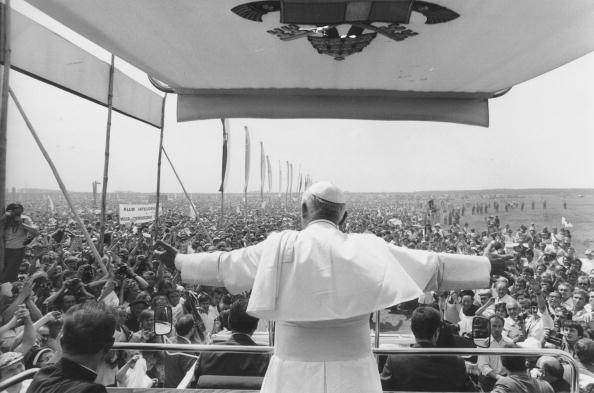

John Paul II’s papacy was dramatic and historic on many fronts. We explore some of the critical religious issues of his 26 years as pontiff and discusses the great and contradictory impact he made on the Catholic Church in America and abroad.

Image by Keystone/Getty, © All Rights Reserved.

Guests

Sylvia Poggioli is senior European correspondent for National Public Radio's foreign desk.

Donald Cozzens

Margaret A. Farley is Gilbert L. Stark Professor of Christian Ethics at Yale University Divinity School.

Transcript

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: This is Speaking of Faith, conversation about beliefs, meaning, ethics and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today, The Religious Legacy of John Paul II, who has died at the age of 84 after 26 years as pontiff. On October 16th, 1978, a thin line of white smoke rose from St. Peter’s Square in Rome, signaling the election of Cardinal Karol Wojtyla as the 264th pope of the Roman Catholic Church.

The pope is the spiritual head and chief pastor of over one billion Roman Catholics worldwide. He is the bishop of Rome and, according to Roman Catholic doctrine, a direct successor of the apostle Peter, which links his authority to the earliest Christians. In the Aramaic language that Jesus spoke, the name Peter is identical with the word “rock.” And it was to Peter that, in the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus proclaimed, “Upon this rock I will build my church.” John Paul II assumed his role at a dynamic moment in the life of the church and the world. The Second Vatican Council had ended 13 years earlier, and the church was just beginning to grapple with many of the changes the council had set in motion. Then, just a decade into his papacy, this former archbishop of Krakow became a symbol of the astonishing fall of communism. In the 1990s, the East/West divisions of the Cold War receded, but globalization rapidly brought into focus what began to be called the “North/South divide” — economic disparities between industrialized and developing societies. Church teachings clashed increasingly with profound changes in the United States and Europe concerning the family, the role of women, and medical technologies.

Pope John Paul II expanded what became known as a “consistent ethic of life,” linking issues of genetics, abortion, capital punishment, warfare, and the care of the terminally ill. He criticized what he saw as a disregard for life in many Western legal and social and economic structures, and he deemed them “cultures of death.” Yet even as he critiqued modern culture, John Paul II reached out in new ways to Catholics all over the world, speaking directly to them in their own languages.

POPE JOHN PAUL II: To all of you who speak English, I count on the support of your prayers in carrying out my mission of service to the church and mankind. May Christ give you his grace.

MS. TIPPETT: This hour we’ll analyze the contributions and complexity of Pope John Paul II. We’ll probe critical themes of his theology, his controversial approach to sexual ethics, and the mark he made on the lives of modern Catholics. We begin with National Public Radio’s senior European correspondent Sylvia Poggioli. She reported on John Paul II from his first day as pontiff. I wanted to draw Sylvia Poggioli out on her impressions of him as a man and a religious public figure. She recalls the tremendous vigor with which John Paul II first took office — a vigor that was easy to forget in recent years as the pope grew ill and frail in public view.

SYLVIA POGGIOLI: What he looked like at 58, it was incredible. And his voice, too. What he sounded like on October 16th, 1978, the day he was elected pontiff, he was a very powerful physical figure. I mean, strong, imposing and very athletic. There were a lot of these monikers of “the pope’s athlete.” He went skiing, he went swimming. I mean, it was really quite something.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. He was actually the youngest pope for 200 years. Obviously, what was also so striking was that he was the first non-Italian pope for something like 500 years.

MS. POGGIOLI: Absolutely.

MS. TIPPETT: Tell me, from the vantage point of Italy, why that mattered, what it meant.

MS. POGGIOLI: I remember the impact. I remember hearing on television when the cardinal came out and said in Latin, “Habemus papam,” `We have a pope,’ and said his name. And it was not a name that many of us — you know, anybody, certainly not the crowd in the square — had heard of. And I think at first many people thought it sounded like an African name, Karol Wojtyla. Nobody really knew what this name was. It was very, very, very exotic. And I think he was definitely exotic from day one. To analyze the papacy, or any papacy, from the point of view of the people of Rome is always a bit skewed. I mean, this is a city that’s lived with the Catholic Church — the institution, the Vatican — for 2,000 years, and to say that Romans are somewhat cynical, skeptical, I think, would be an understatement. It is not a very religious city. Also because during history, you know, many times the papacy was,-the Vatican was an oppressive force here. So it’s hard to say. I mean, I think there was no problem, for most people here that he was not an Italian pope. Rome was immediately transformed. There was a huge influx of Poles. Meaning not just people at the Vatican, but really many Poles came to Rome, to Italy, to work. And it was different. I think today there’s a lot of — analysts are speculating so much on whether the next pope will be again an Italian. And they say the presence of the Italians has weakened in the college of cardinals. Of course, they’re fewer than they were before.

MS. TIPPETT: This is true, isn’t it? I mean, in terms of members?

MS. POGGIOLI: Absolutely. But I think now the contrast will be much more on whether it’ll be a Western — let’s say — the United States is excluded for obvious reasons. So let’s say it’ll be either a European or possibly a Latin American. I think that will be the…

MS. TIPPETT: It will be more of a South/North.

MS. POGGIOLI: That will be the line. Yeah. Yeah. A South/North thing. Exactly.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, I want to go into a little bit more what you said about how cynical and areligious the Romans are because actually I’m not sure that a lot of Americans know that or understand it.

MS. POGGIOLI: Yeah, broadly in Europe. I mean, so much of Pope John Paul’s papacy was — certainly the early years, more than anything — it certainly was he put so strongly a conservative stamp on the dogma. And he was so strongly opposed to, of course, to artificial contraception, abortion, opposed to in vitro fertilization. These were all issues which he saw as primarily the concerns of a Western secular culture, which he was always very critical of. And he often branded these societies as “cultures of death.” And I think, certainly, you know, many Europeans did not recognize themselves. Many European Catholics simply do not recognize themselves in this description. And so I think this is where he was certainly seen as an incredibly powerful political figure. I think he had much, much less impact as his papacy progressed on the religious, spiritual sector of European Catholics. I think that the gap grew tremendously. It was a very strong gap.

MS. TIPPETT: I want to try to get into something of this mystery and mystique cround the papacy, even how you’ve seen that expressed maybe as much when John Paul II traveled, which he did a remarkable amount.

MS. POGGIOLI: I think he became probably the most recognizable face in the world. No face was better known than that of the pope. He attracted massive numbers of crowds. No previous pope had traveled even a fraction of what John Paul II — I think Paul VI went once to Israel and, perhaps, once to New York to the United Nations, and made perhaps a few European trips, or very, very little. This was a complete revolution. He brought the papacy to the Catholic world. He took it out of Rome, and it became a kind of traveling Vatican in a sense. He brought the message of the spiritual leader of the world’s Catholics. He went to look for them. And this was an incredibly important thing. I think this has been probably one of the major, major impacts of this papacy. But again, yes, an international media star. He was extremely, extremely able in understanding the use of television, of mass media, broadcast media in particular. However, again, as I say, the impact has been very different in the North/South, Europe vs. the developing world. For instance, Europe, a country like France, the great majority of the population proclaims itself Catholic, but only 12 percent regularly go to church. Churches are beginning to be empty in Europe. Sixty-eight percent of Catholics now are in the developing world — Latin America, Africa and Asia. But the power base is still the West, the United States and Europe, and the money comes from the United States and from Germany, from many European countries. So where is its future going now?

MS. TIPPETT: Journalist Sylvia Poggioli. When he became pope, Cardinal Karol Wojtyla of Poland personified the great divisions of Europe. He had lived through the Nazi occupation of his country. He became archbishop of Krakow in communist Poland. He had no direct experience of a free and democratic society, but the Catholic Church in Poland was the only forceful religious institution in communist Eastern Europe, and it was a center of resistance. In the Poland that formed John Paul II, theological conservatism was a revolutionary stance. Sylvia Poggioli suggests that this history helps explain why he was often seen as both authoritarian and radical.

MS. POGGIOLI: There are some wonderful and fascinating stories about Karol Wojtyla when he was archbishop of Krakow, and he was really a militant fighter for the church. He had organized illegal teams that would build churches in lightning speed overnight because there was a Polish law that once the roof was over a building, you know, you couldn’t knock it down. And so there’s a working class area that was just outside the Krakow called Nova Huta, which was built — it’s sort of like this Stalinist dream town. It was built with no churches. And this was one of the places where all these teams of militant Catholics would be building churches. And finally they reached an agreement with the Catholic Church, and this large, large church called The Ark was built. But it was the only one that was permitted by the Communist regime. And this was his thing. He was proud to say that he never shook hands with a Communist official. And this is what he brought, certainly, this kind of intransigeance is what he brought to Rome as pope, but it’s an institution that also has to deal more with compromise and with diplomacy. And John Paul II always proclaimed his total belief in the reforms of the Second Vatican Council. But essentially, Eastern European countries under communism did not have the experience that the American and West European churches did of applying those reforms. And in a sense, that’s what another one of the certainly liberal critics criticize John Paul for, not having really digested and really taken these reforms further. And he was actually seen as having pushed the church back.

MS. TIPPETT: What are your most vivid memories just as a journalist covering him?

MS. POGGIOLI: I think that there are some amazing visual impacts. I certainly remember in 1981 when he was shot. We saw this body slumping over in the car and nobody really knew what had happened. And then only a few years later we saw Pope John Paul II huddling in a prison cell in Rome talking to his would-be assassin, Mehmet Ali Agca, and forgiving him. Another very powerful image was when he went to Nicaragua to admonish the priests who had taken part in the Sandinista government. And he raised his — wagging his finger at Sandinista priests. Another, for me, extremely powerful, perhaps the most powerful image I certainly recall, was in the year 2000 in Jerusalem when, already bent and his sickness already beginning to be very visible, when he went to the Wailing Wall and placed his hand and left his prayer and the document where the Vatican basically asked forgiveness for Shoah, for the Catholic Church, and he placed this at the Wailing Wall. And this, I think, was one of the most powerful images I certainly remember. I was there.

MS. TIPPETT: If you think about, let’s say the apostolic letters or theological pronouncements that have come out of the Vatican in this period, these last few decades, can you think of something that most surprised you in the impact it seemed to have as a spiritual document, as a theological document. What comes to mind?

MS. POGGIOLI: Well, so many of them have been concerned with social issues also. Not just, I mean — and proclaiming doctrine and authority of doctrine. I think it’s very difficult. Perhaps what I think is most, in a way, interesting is his condemnation — well, again, it’s a more political thing — his tremendously strong condemnation of capitalism and of consumer society. It was a very surprising thing when he went — in 1993 he went to the Baltic states, and they had just been recently freed from — become independent from the Soviet Union. And he stunned he people there when he said that there was kernels of truth in Marxism. And he said that the seeds of truth in Marxism shouldn’t be destroyed, they shouldn’t be blown away, and that the supporters of capitalism in extreme forms tend to overlook the good things achieved by communism. I think this was seen by many analysts as, perhaps, you know, an almost rethinking. What happened is his battle against secularism became even more challenging in his papacy after the fall of communism.

MS. TIPPETT: Oh, that’s fascinating. Clare Boothe Luce once famously said that history has time to give each great man only one sentence. If you were writing that sentence about Pope John Paul II, how might it go?

MS. POGGIOLI: Well, I have to say what he said. I guess it was one of his very first statements, and it’s sort of been, I guess, really the slogan of his papacy, and it’s certainly, when we think of what he meant looking towards Eastern Europe that was then under communism, it was “Open up your doors to Christ.”

MS. TIPPETT: NPR’s senior European correspondent Sylvia Poggioli. Here is the voice of John Paul II in the fall of 1979 arriving in Dublin for the first papal visit in the history of Ireland.

POPE JOHN PAUL II: It is with immense joy and with profound gratitude to the most Holy Trinity that I set foot today on Irish soil. [Foreign language spoken]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today we’re exploring some of the complexity of the papacy of John Paul II who has died at the age of 84. My next guest, Father Donald Cozzens, is a diocesan priest and writer in residence at the John Carroll University in Cleveland. He’s the author of several respected books on the Catholic priesthood and the culture of the Catholic Church. Like many Roman Catholics, he says, he had great personal admiration for Pope John Paul II. At the same time, he’s ambivalent about the late pontiff’s legacy. In religious terms, he says “this pope sent conflicting messages, which made him impossible to categorize as conservative or liberal. Donald Cozzens was in seminary in the early 1960s, during the years in which the Second Vatican Council met and set in motion a widespread worldwide re-examination of Catholic teachings and practices. Cozzens’ own sense of his priesthood and the church evolved in the period that followed. Though John Paul II was not the first pope after Vatican II, his theological and ecclesiastical stances were always examined in the light of the promises, fears and hopes the council created. Pope John XXIII had convened that worldwide gathering of the church, he said, quote, “to shake off the dust that has collected on the throne of St. Peter since the time of Constantine, and let in some fresh air.” Vatican II began to open up Catholic thought and doctrine, leading to a less hierarchical governance, increased roles for the laity, and Masses spoken in native languages rather than intoned in Latin.

DONALD COZZENS: You know, Krista, it was a very exciting time, of course. And here’s the paradox: The four years I spent in theology from 1961 to 1965, I was really being trained in a pre-Vatican II seminary. But at the same time, hearing of reports from Rome and the council that were very exciting, and in many cases contrasted with what we seminarians were being taught in the classroom. So in a way, I was ordained in 1965 with the pre-Vatican II seminary program of formation for a post-Vatican II church. The times were filled with excitement, anticipation, and we all knew this was a watershed mark for the church.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm. And would you say that, at least where you were, was the mood one of hope or of anxiety, of fear, or was it a combination of those things?

FATHER COZZENS: Very definitely it was a mood of hope and anticipation, and a great sense of joy and excitement that the church was, in a sense, opening windows and looking at the modern world without fear as an eager participant in the issues of not only our nation, but of the world.

MS. TIPPETT: What I’d be curious about is, as you personally watched the trajectory of him being elected pope, talking about carrying on the legacy of Vatican II, how did you see that unfold, or did the course of that change during those years?

FATHER COZZENS: I think from the very beginning he seemed to be somewhat conflicted. I believe with all my heart that he embraced the vision of Vatican II. Now, his reading of that vision is certainly being disputed today, especially things like that collegiality of the bishops, and the call to dialogue, openness to other religions. All of that, I think is somewhat cloudy today.

MS. TIPPETT: If I ask you, from a theological standpoint and for you as a theologically minded priest, you know, what are the most important teachings and messages that this pope sent, what comes to mind for you?

FATHER COZZENS: Well, his first encyclical, Krista, which was issued only a year after he was elected pope, is entitled “Redeemer of Humanity.” And in this first encyclical, he stressed the dignity and worth of every human person. He deplored the exploitation of the earth and the destruction of the environment, and he condemned consumerism and the accumulation of wealth and the misuse of goods that might cause the poor of the world to suffer. He condemned the arms race, which was still raging at that time. And he condemned all violations of human rights around the globe. So that first encyclical, in my judgment, was very prophetic and very important. His teachings since that time, of course, pleased some and displeased others. But that first encyclical, I think, was one of the major documents of his early years as a pope.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, it strikes me that some of his language about capitalism, some of the things you’ve just mentioned, especially in the late ’70s, to American ears sound pretty radical and leftist.

FATHER COZZENS: Absolutely. John Paul II, with the encyclical that I just mentioned and in other subsequent pronouncements that he made, made many conservative, very wealthy Catholics quite nervous because he was calling for a kind of global consciousness that would put concern for the poor of our world in an uppermost position. So conservative Catholics today, who want a very strong, almost rigid papacy, were quick to criticize John Paul II for, you know, calling upon us to take a serious, considered review of unmitigated capitalism.

MS. TIPPETT: Priest and author Donald Cozzens. John Paul II wrote an extraordinary number of papal encyclicals, or official letters laying out church teachings, as well as other kinds of exhortations, homilies and messages. These were addressed to fellow bishops or to all the faithful. Here’s a reading from a 2001 encyclical, “Centesimus annus,” in which the pontiff again addressed capitalist and consumer society.

READER: “It is not wrong to want to live better. What is wrong is a style of life which is presumed to be better when it is directed towards having rather than being, and which wants to have more, not in order to be more, but in order to spend life in enjoyment as an end in itself. It is therefore necessary to create lifestyles in which the quest for truth, beauty, goodness and communion with others for the sake of common growth are the factors which determine consumer choices, savings and investments.”

MS. TIPPETT: This is Speaking of Faith. After a short break, more of my conversation with priest and author Donald Cozzens. Also, Yale theologian Margaret Farley on sexual ethics and the papacy of John Paul II. I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us.

Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, conversation about beliefs, meanings, ethics and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett. Today we’re analyzing some critical themes in the religious message and impact of the late Pope John Paul II. Karol Wojtyla was a philosopher, athlete and linguist who became the youngest pope in 200 years, and the first non-Italian pope since the 15th century. Here he is singing in his native Polish in the spring of 1979 in the first months of his papacy at an open-air service in Krakow.

[Audio clip of Pope John Paul II singing at 1979 service]

MS. TIPPETT: In recent years, many trends in American culture ran counter to the teachings of John Paul II. I’m speaking with Catholic priest and author Donald Cozzens on the complicated legacy of this pope.

MS. TIPPETT: One American journalist wrote that `John Paul II was loved, admired, respected and adored, but often ignored,’ that Catholics felt freer than ever before to ignore the teachings of the church. And I’m thinking, in particular of something like birth control. Is that about John Paul II or is it about the time in which we live?

FATHER COZZENS: Well, that’s a very good question. I think it’s both. I think it’s about the pope, but also the time in which we live. I’m teaching now at John Carroll University in Cleveland and had two classes today. And I asked both of my classes what their impressions were of Pope John Paul II. And their response was very similar to what you quoted earlier, that almost universally John Paul II is admired, respected, people have a great regard for this brave and holy and intelligent man. But almost to a person, the relevance for John Paul II and his teaching office in the lives of the students seemed to be minimal.

MS. TIPPETT: So how do you explain that?

FATHER COZZENS: Well, I think the Second Vatican Council more or less liberated the imagination of Catholics. I think Catholics are very committed to the gospel. They’re also committed to the sacramental life of the church, and they’re also committed to the institutional church, but now they are `thinking Catholics,’ if I can use that expression, and they’re looking for intelligent explanations of the gospel and why leading a Christian life is so relevant for society, for our culture and for their own lives. All of this converges to a new day I think you might say. It makes the challenge of the papacy almost overwhelming.

MS. TIPPETT: Now, you’ve written a lot about the new generation of priests and then you’ve been talking to me about this liberation of the imagination of Catholics. Is there a disconnect between that, between what’s happened in our culture, which is more of an opening, and the kinds of people who are becoming priests in our time? And what does that say about how the church of the future might look?

FATHER COZZENS: A penetrating question. I think a number of seminarians today are looking for very clear teachings, and they seem to be struggling with the ambiguity that is so profoundly connected with human life and human experience. So these seminarians want to know what is true and false, what is right and wrong, what is good and bad. And they want to know that clearly. My concern is that as these men move through their seminary training and approach ordination they will find themselves ministering to Catholics today whose religious imagination is quite different from their understanding of God and sin and punishment and reward. So it could really signal some rough times ahead for the pope who will be succeeding him. When you raise the issue of culture, this is one of the strong suits of John Paul II’s reign as pope. I think he clearly identified some of the weaknesses of Western culture in particular. He pointed out that our culture is characterized by a radical individualism, calling for, not only those of us who live in the West, but all of the people of the earth, to see that a radical individualism is going to be very destructive if we do not embrace and hold forth the ideal of a commitment to the common good. So some of the cultural tension between the West and the teachings of the church and the Vatican, I think that’s a healthy tension. But there also is, yes, a split in, say, the American Catholic culture and the culture of the Vatican. I think we Catholic Americans have a regard and a respect for a more democratic approach to issues within the church and life in general than does the culture of the Vatican.

MS. TIPPETT: What is the sentence that you think history might give to John Paul II?

Father Cozzens: `Treasure and prize the least among you, the poor and the homeless.’ I think his one great sentence will be a very strong and consistent voice for the underdog, the underprivileged of the world.

MS. TIPPETT: Father Donald Cozzens teaches religious studies at John Carroll University in Ohio. His most recent book is Faith That Dares to Speak.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today we’re exploring the religious legacy of the late John Paul II. No set of teachings which this pope inherited was as controversial as that on human sexuality, including artificial contraception. My next guest, Margaret Farley, suggests that most of the other most-controversial social and sexual policies of the Catholic Church flow in some sense from this: The consistent ethic of life which John Paul II championed extended the church’s regard for the sanctity of life at conception to other moral quandaries about the beginning and the end of life. Margaret Farley is a Catholic nun and esteemed theologian and moral ethicist.

MARGARET FARLEY: I started teaching at Yale Divinity School in the early ’70s. That was a time right after the Second Vatican Council of great hope. And I must say, especially great hope for women because there was hope even for ordination of women. There was hope for new possibilities not only in ordained ministry but in lay ministry and so on. Of course, John Paul II wasn’t the first pope after Vatican II. Pope Paul VI was still in place for the last sessions of the Vatican Council, and for the years after that. No change as great as this change was could be without disruption. And so tensions were already being felt. But when John Paul II was elected pope, here we had a man at that time still relatively young, as popes go, and vibrant and seemingly open to all kinds of important things, particularly social justice issues around the world, and a brilliant man and, as proved to be true through his years, a very holy man. But if you ask what he did, I would have to say, from my vantage point, overall more of a reversal of some of the things that had looked so positive in the Second Vatican Council. Or certainly a dampening of the optimism that had been there right after the Council.

MS. TIPPETT: Just give me some specific, some important issues for you, especially when you talk about a reversal, I mean, some very concrete examples of where you’ve seen that.

SISTER FARLEY: Questions, particular questions in sexual ethics and in medical ethics. So these are the standard difficult questions that have been problematic in the Roman Catholic Church for a long time.

MS. TIPPETT: And you know, it’s striking that he became pope in 1978, and the first what we called then “test-tube baby” had just been born, the first in vitro, right? So, I mean, in this time of his papacy, also these issues of sexual and medical ethics have become remarkably more complex.

SISTER FARLEY: They certainly have. All of them probably have become more complex, certainly the ones in medical ethics like stem cell research or, on the horizon, cloning, or in vitro fertilization. All the forms of infertility treatment and so on have complicated matters. Although I think it all comes down in the Roman Catholic struggle over these issues to just a few issues. But even questions of divorce and remarriage, which you could say, `Well, what’s new about that?’ But that’s more complex, too, because life is more complex. People live longer and live in different circumstances. The issue of homosexuality has, of course, grown ever since the gay rights movement. The abortion issue has become politicized to a degree.

MS. TIPPETT: I guess in these kinds of areas, cultural norms have changed and that has been pressed back on doctrine and theology?

SISTER FARLEY: I think, yes, cultural shifts have given new questions and new insights. But when I say that, so many of these are focused on just a few issues. For example, the issue of contraception. After all, “Humanae Vitae” came out in 1968, just after the Vatican Council, and that, too, was a watershed.

MS. TIPPETT: Catholic theologian and ethicist Margaret Farley. “Humane Vitae” was an encyclical issued in 1968 by Pope Paul VI, John Paul II’s immediate predecessor, just three years after the Second Vatican Council ended. It reinforced the church’s prohibition on birth control. Vatican II had asserted for the first time in Catholic doctrinal history that human sexuality was not meant solely for the purpose of procreation, but was also in and of itself a positive aspect of marital relationship. In that same period, the birth control pill was making reliable contraception universally available for the first time and changing sexual norms. Many Catholics anticipated the church would soon sanction its use within marriage. Here is a section of “Humanae Vitae” which stunned many in the Catholic world.

READER: “The church teaches that each and every marital act must of necessity retain its intrinsic relationship to the procreation of human life. The reason is that the fundamental nature of the marriage act, while uniting husband and wife in the closest intimacy, also renders them capable of generating new life, and this as a result of laws written into the actual nature of man and of woman. We believe that our contemporaries are particularly capable of seeing that this teaching is in harmony with human reason. If they further reflect, they must also recognize that an act of mutual love which impairs the capacity to transmit life, which God, the creator, through specific laws has built into it, frustrates his design.”

MS. TIPPETT: From the 1968 papal encyclical of Pope Paul VI “Humanae Vitae.” Now back to my conversation with moral ethicist Margaret Farley of Yale.

SISTER FARLEY: I, myself, think the process of final decision, the final writing of that document, the arguments that were in it and the position that was taken, which was counter to what everyone expected, takes on dimensions of almost tragedy in the life of the Roman Catholic Church. And the contraception issue is the issue that’s involved with infertility treatment. I mean, the whole issue is, what is sex for? How does it have to be connected with procreation of children? I mean, Vatican II at least made the marvelous change in theology of marriage and theology of sexuality when it said that the primary purpose of human sexual activity is not procreation, or having offspring, but rather that there are two equally important purposes for sexuality. There is the purpose of producing offspring, perpetuating the species, yes, but also the issue of the relationship between married partners. When that was said, that was a major change in Roman Catholic sexual ethics. I must say that in all the strands of Christianity, not much happened in sexual ethics until the 20th century. They all had the same rather pessimistic view of sexuality as such, the same concern that St. Paul had for marriage as a remedy…

MS. TIPPETT: `If you must.’

SISTER FARLEY: …against — yes, that’s right. And the protestant traditions did not emphasize the procreative ethic in the same way that the Catholic tradition continued to do through the centuries, but still, it was there. But when, in the 20th century, effective means of contraception were available on a wide scale, that changed the whole question. And the Roman Catholic official teaching, of course, did not change. And that’s why we have this cosmic struggle. Well, on the one hand a cosmic struggle, on the other hand it’s become a nonissue for new generations of Roman Catholics, I’m afraid.

MS. TIPPETT: Theologian and ethicist Margaret Farley. When he became pope in 1978, many Catholics believed that John Paul II would finally modify or reverse the church’s policy on contraception. He did not, but he wrote extensively and creatively on matters of human sexuality. For example, in one papal audience he said, quote, “How indispensable is thorough knowledge of the meaning of the body in its masculinity and femininity. How necessary is a precise awareness of the nuptial meaning of the body of its generative meaning.”

SISTER FARLEY: All of that added up to a set of arguments against premarital sex, against adultery, against contraception, against homosexuality, against abortion. Now, I don’t want to imply that that’s a wrong-headed way to address those issues, but they have to be dealt with in their own right. I mean, in my view, the issue of abortion is a generically different issue than contraception, for example. And in fact, one of the problems in the Roman Catholic tradition is that if we want to hold the line against abortion, it just doesn’t make sense to hold the line against contraception. At the same time, Roman Catholic moral theologians are developing positions that are in great tension and sometimes in opposition to the official teaching of the church, and that has created a very troublesome situation in the church.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, so I think this is something that people outside are very curious about, what sort of influence has this pope, John Paul II, had on the work of theology?

SISTER FARLEY: Well, to some extent, I would say, sadly, it has had the effect on some moral theologians that they don’t write on these issues anymore. They write on safer issues. But I think that’s a minor effect. I hope it is, anyway, and I hope it will continue to be only that. Because otherwise, I think, first of all, Roman Catholic moral theologians are not all members of the clergy anymore. They are lay persons. They are women; they are men. And the way I describe it, they do their job, which is, they have a job within the church. They have a vocation within the church, which is to contribute to the communal discernment of all the faithful, including the church leaders, on difficult moral issues, complicated moral issues. I mean, sometimes I say that deep in the Catholic psyche is the belief that morality ought to make sense. The reason for that is the Catholic tradition is the one Christian tradition that has always sustained a certain amount of optimism about capacities of human reason, and has always sustained a conviction that creation is revelatory, that it’s knowable, that it reveals God’s will in addition to the Bible revealing God’s will.

MS. TIPPETT: I think you especially stress this in your work, the importance of lived experience, human experience, as a force in theology, right?

SISTER FARLEY: That’s right. Or even in interpreting the Bible or the tradition. It has to make sense. And so I think we have very strong positions, which are different than official teaching, on divorce and remarriage, certainly on contraception, on homosexuality, and to some extent on abortion.

MS. TIPPETT: So this tension between not only what moral theologians are discerning, but also what medicine is discerning in our time, this tension between the theology that’s being done and the teachings that seem to come out of the Vatican, now, do you think that that tension has been greater under John Paul II? But then, you know, just as you get into some the details of that, I wonder, again, if that’s not inevitable because of this huge pace of change.

SISTER FARLEY: I think it may be inevitable, but I also think that the fact that some of these issues have become so politicized has been the reason why they’ve also become polarized. I mean, the teachings are not changed, but the escalation of the importance of them, as if they were the litmus test of what it means to be a Catholic, rather than the doctrine of the Trinity and the incarnation and so on. I mean, I think that is new. I really do.

MS. TIPPETT: We haven’t talked about the sexual scandal, but obviously sexual ethics is a field in which you’re very active. And I want to ask you a very focused question. In what way can you imagine that the sexual scandal will be portrayed as part of the legacy of John Paul II?

SISTER FARLEY: I’m not sure I know the answer to that question. I perceive the Vatican as a marginal player in this regard. Now, maybe that’s part of the problem, but I think that those on the scene here should have been able to handle it, should have done better than they did. Clerical culture has a lot to do with how the problem occurred in the first place, but it didn’t have to get to the point that it got to.

MS. TIPPETT: The Catholic Church in particular in Rome, and the figure of the pope, has a mysterious power. You know, Gary Wills, who’s been a great critic of the papacy, says that Rome has this power to attract energies and generate energies around the symbol of Peter. I just wonder, as a woman, as a Catholic theologian, you know, what is that power of Rome in your life been like?

SISTER FARLEY: Well, I don’t know if I would describe it as a power of Rome. Although, I sometimes, half joking but half serious, say `Well, the Roman Catholic Church is the one place in the world where you can really engage in cosmic struggles over very important matters without going to war.’ But I constantly get asked, `Why do you remain a Roman Catholic?’ And I have one answer, and that is because the Catholic Church is still a source of life for me. The Catholic Church is a worldwide community with a tradition that’s rich, as rich as you can imagine theologically, that’s pastoral in ways that are almost unparalleled around the world. The Catholic Church has a sacramental system that gives food to the hungry, the spiritually hungry, and drink to the spiritually thirsty. Thomas Aquinas worked on controversial issues, for goodness sake. To be Catholic does not mean that you agree with every single thing that a present pope or a present bishop teaches. That has never been the case in the Catholic community. The job of the theologian is to speak out of and back into a faith community as she or he does the work of trying to understand what it is we believe, and as a moral theologian, trying to understand how we are to live what we believe. I mean, this is a wonderful vocation in a wonderful church.

MS. TIPPETT: Margaret Farley holds the Gilbert L. Stark Chair in Christian ethics at Yale University Divinity School. Earlier you heard priest and author Donald Cozzens and National Public Radio correspondent Sylvia Poggioli. Pope John Paul II was at once orthodox and revolutionary, conservative and liberal. In this he resisted another American cultural trend: our tendency to classify in order to either endorse or condemn. The man born Karol Wojtyla is intriguing precisely because he was so widely beloved even by those who disagreed with him. These glimpses given by Sylvia Poggioli, Donald Cozzens and Margaret Farley reveal him as a gracious, if controversial, bearer of all the complexity of our time, from fascism and war, to communism and the newer possibilities and perils of a global age. He might also be the last pope raised in a pre-Vatican II world to lead a post-Vatican II church. As we have heard, this new day in the church makes the challenge of the papacy, to repeat Father Cozzens’ phrase, “almost overwhelming.” The church, any church, but especially the ancient institution of Rome will never evolve as rapidly as culture. Culture, on the other hand, cannot stop bounding into new territory and new dilemmas. Still, John Paul II was ahead of the popular curve as an early champion of environmentalism and the wisdom of limiting consumer society. Some papal teachings may be widely dismissed, including by many Catholics, but questions which the Vatican has kept alive about when life begins and how that should shape public policy are reborn every day in American life. There are many important topics of interest to Catholics and others that we did not touch on in this program, issues that will continue to unfold and be handed on to the next pontiff. But the voices of this hour do evoke the breadth and depth of this pope’s life and thought, the mark he made on the world. They leave us with a sense that the papacy itself and, in particular, the legacy of John Paul II has been important whether we are Catholic or not.

We’d love to hear your comments on this program and your thoughts on the papacy of John Paul II. Please write to us at speakingoffaith.org. On our website you can also listen to this program again and to our previous programs.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.