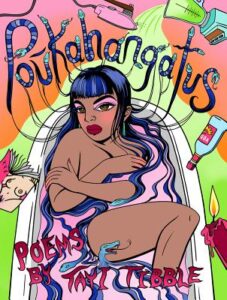

Tayi Tibble

Our Nan Lets Us Smoke Inside

Who is in your chosen family?

This poem considers the lines of loyalty in families and how particular memories, like a grandmother keeping “wishbones from chicken carcasses / in an empty margarine container on top of the fridge,” can be a portal to love. The nan in this poem is a character of generosity and permission, and we imagine her through stories of trips, funerals, and visits.

Image by Expedition Press/Expedition Press, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Tayi Tibble is a writer and poet who lives in Wellington, New Zealand. In 2017 she completed a Masters in Creative Writing from the International Institute of Modern Letters, Victoria University of Wellington, where she was the recipient of the Adam Foundation Prize. Poūkahangatus is her first book.

Transcript

Pádraig Ó Tuama, host: My name is Pádraig Ó Tuama, and poetry has changed the way I think about confession. Rather, I grew up hearing that confession was about confessing your wrong. But These days, I think of confession as confessing your truth, confessing what matters in a life, and confessing the thing that you mightn’t have told but that holds you together.

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: “Our Nan Lets Us Smoke Inside” by Tayi Tibble:

“Our nan lets us smoke inside

but only when we drink wine and play cards

on the kitchen table. I feel glamorous

when I drop my ash into the pāua shell in the middle.

Our nan wears black leather pumps

and dries wishbones from chicken carcasses

in an empty margarine container on top of the fridge.

She’s not my real nan

but I’ve always wished she was.

I wished I was born with her

blood in my veins, her dark

Waikato DNA, high cheekbones

and heavy wet eyes just like my sister.

Our nan met her late husband

in the late sixties. She was dressed

in a little mod dress, her black hair flipped.

He was a cowboy with mutton chops and

tan-lined legs and short cream shorts, who rode off

to work every morning with a commercial digger for a horse but—

he’d pick us up in his station wagon on Sundays.

Johnny Cash and his metronome voice

making us fall asleep against the dusty windows so we would stop

for a Filet-O-Fish and a strawberry milkshake

for lunch and dinner. But he always picked

my sister up more.

At his funeral,

us girls carried the mismatched flowers

behind our brothers in black sunglasses.

At the service,

we all got up and sang I hope you are dancing in the sky

but it was painful and flat and sounded like coughing.

During the burial,

nobody exhaled a word as my nan ashed out

a half-sucked cigarette in the fresh sour soil.

In the carpark,

we all smoked back tears with another cigarette pacifier

like babies numbed on a nicotine nipple.”

[music: “Every Place We’ve Been” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: I think Tayi Tibble is remarkably brave and brilliant in many of her poems. And in this one, I think she tells the story of a funeral where the funeral is a bit of a relief, in that the funeral opens up the possibility of safety for discussing things that would not have felt safe in advance of this person’s death.

I suppose there are so many different kinds of deaths, as well, and sometimes you’re at a funeral of somebody that you either didn’t know or you didn’t care for, or, even in a family context, where they paid more attention to somebody else, rather than you. And so you don’t feel personally, hugely grieved. And there’s a strange kind of observation that happens in those funerals. And I think that’s such a brave thing to name, because, so often, we seek to maybe turn a bit romantic, when it comes to a funeral, and somebody who we mightn’t have had too much time from or for, during their life, when they die you might suddenly place yourself at the center of a drama that involves them and you. And this poem is so brave. It just seems to imply that really, she’s still got most of her attention towards her nan. And she’s particularly paying attention to being with her. And the death of the man that the nan was married to seems to happen to the side.

[music: “First Grief, First Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: Tayi Tibble speaks about this woman as her nan, and she speaks about her nan’s husband. So she doesn’t call him granddad, but, clearly, he’s part of this network that’s been important to her for a very long time. But even with so much proximity, and even with so many memories of being picked up in a station wagon and going for fish and chips and strawberry milkshakes, you can still feel like a stranger around somebody who was part of your everyday backdrop, family by blood or family by circumstance or family by choice.

The nan is family by so many things — she wishes it was blood, but, clearly, they are absolute family to each other.

The magnificence of the character of the nan: she lets the girl smoke inside; and everybody loves to have a family member, family by choice or family by blood, who you don’t feel like you’ve got to have airs and graces around. And she clearly has a great eye for fashion — she’d worn black leather pumps and that she’s described as having had great style. And she keeps the bones of chickens — she’s thrifty — she clearly is a person of economy. And the poet feels glamorous, dropping ash into the pāua shell. Pāua is a beautiful shell you find all around New Zealand, magnificent turquoise colors in it. And so she seemed to be a person who gathered an intergenerational community around her and that, while there was deep love and deep affection and deep recognition of wisdom and culture and heritage, there also was magnificent trust. You get the impression that the nan was a person to whom you could confess the truth of your life and that she’d listen and understand, rather than being cast in a figure of somebody who would dispense unwanted advice or wouldn’t understand you in the first place. And the story of this funeral is cast against this moment of Tayi Tibble wondering, What does it mean to be present to her nan, when her nan has been present to her?

[music: “Ashed to Air” by Gautam Srikishan]

Ó Tuama: The craft of this poem is quite brilliant. It’s mostly in three-line verses, and the four final stanzas read like a slow drumbeat, to me. They do seem almost like a slow march toward a funeral. The four final stanzas each begin with three words that are so striking: “At his funeral,” “At the service,” “During the burial,” “In the carpark.” The opening of this poem is looking back with great reminiscence over what seems like years, all of these memories of childhood and time spent around the table and chicken wishbones being dried in a margarine container on the top of the fridge. And that seems to be something that happens so regularly that you feel like you’re casting a gaze back through Tayi Tibble’s childhood, running through many years.

But then, suddenly, the timing in this poem slows down, just like timing does when you’re at a funeral: “At his funeral,” “At the service,” “During the burial,” “In the carpark.” And we’re with them, we’re observing and we’re watching, and we see a community of people who are finding solace with each other. I love how she makes the poem do this, without narrating it; that we’re brought in through her craft, into being drawn around this complicated moment of death and complicated moment of memorializing.

[music: “Fjell Flor Vjell” by Blue Dot Sessions]

Ó Tuama: I think there is culture happening here, there is a gendered expectation of culture. Tayi Tibble is Maori, the indigenous people of the Aotearoa, New Zealand. And obviously, so is this woman, the nan. She’s got her “dark Waikato DNA, high cheekbones / and heavy wet eyes just like my sister.” And so, within that, you really hear that there is affinity, in terms of a language and a culture, and a culture that’s been colonized and oppressed in New Zealand. I get the impression that the man that the nan was married to was white, “tan-lined legs and short cream shorts.” I could be wrong, but just the impression about how she describes tan-lined legs like that made me wonder, was there something about him being a white guy in the midst of a community of people who were Indigenous, and a community of women who had found tremendous nurture and support with each other?

And that’s what’s so good about Tayi Tibble’s poem, is that you see the way within which this community of women come back together in the carpark at the end: “we all smoked back tears with another cigarette pacifier like babies numbed on a nicotine nipple” — such strong words there. And then the repetition of “numb,” “nicotine,” “nipple,” you’re just brought into this small community of repeated sounds, which is like a community of these people breathing deeply into their lungs in order to provide each other some kind of consolation.

[music: “The House You Wake In” by Gautam Srikishan]

“Our Nan Lets Us Smoke Inside” by Tayi Tibble:

“Our nan lets us smoke inside

but only when we drink wine and play cards

on the kitchen table. I feel glamorous

when I drop my ash into the pāua shell in the middle.

Our nan wears black leather pumps

and dries wishbones from chicken carcasses

in an empty margarine container on top of the fridge.

She’s not my real nan

but I’ve always wished she was.

I wished I was born with her

blood in my veins, her dark

Waikato DNA, high cheekbones

and heavy wet eyes just like my sister.

Our nan met her late husband

in the late sixties. She was dressed

in a little mod dress, her black hair flipped.

He was a cowboy with mutton chops and

tan-lined legs and short cream shorts, who rode off

to work every morning with a commercial digger for a horse but—

he’d pick us up in his station wagon on Sundays.

Johnny Cash and his metronome voice

making us fall asleep against the dusty windows so we would stop

for a Filet-O-Fish and a strawberry milkshake

for lunch and dinner. But he always picked

my sister up more.

At his funeral,

us girls carried the mismatched flowers

behind our brothers in black sunglasses.

At the service,

we all got up and sang I hope you are dancing in the sky

but it was painful and flat and sounded like coughing.

During the burial,

nobody exhaled a word as my nan ashed out

a half-sucked cigarette in the fresh sour soil.

In the carpark,

we all smoked back tears with another cigarette pacifier

like babies numbed on a nicotine nipple.”

[music: “Praise the Rain” by Gautam Srikishan]

Lily Percy: “Our Nan Lets Us Smoke Inside” comes from Tayi Tibble’s book, Poūkahangatus. Thank you to Victoria University Press who gave us permission to use Tayi’s poem. You can find a link to the poem in our show notes, along with Pádraig’s guiding question for this episode.

Poetry Unbound is Chris Heagle, Erin Colasacco, Serri Graslie, Eddie Gonzalez, Lilian Vo, Christiane Wartell, Karen Navarre, Karyn Towey, Sue Ariza, and me, Lily Percy. Our music is composed and provided by Gautam Srikishan and Blue Dot Sessions. This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota land. We also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett, Becoming Wise, and This Movie Changed Me — find those wherever you like to listen or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.