Nishta Mehra

The Namesake

The Namesake, an adaptation of Jhumpa Lahiri’s novel, is a moving exploration of the immigrant experience told through the story of the Ganguli family. The parents, Ashoke and Ashima, marry in India and emigrate to New York state, where they raise their two children, Gogol and Sonia. In tracing the lives of two generations of a family, the movie examines not just the opportunity and promise gained from immigrating to a new country, but also all that is lost from one generation to the next. The wholeness of this depiction offered solace to writer Nishta Mehra after her father’s death. For her, the movie mirrored back the parts of her parents’ lives she did not understand as a young person.

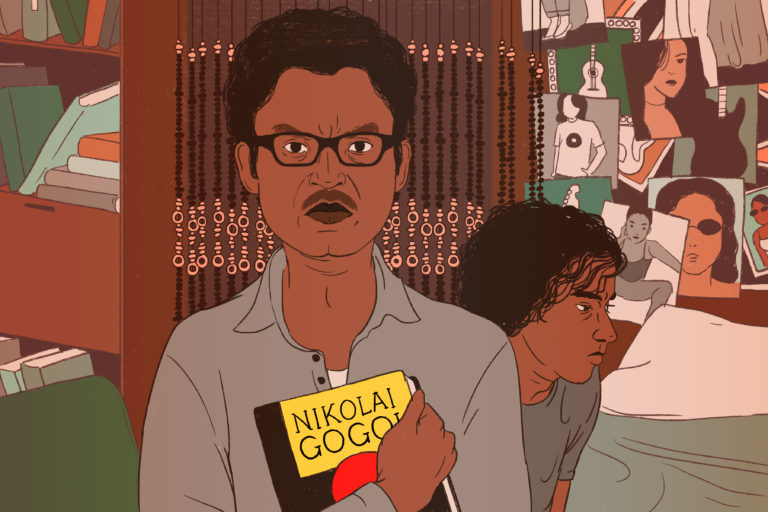

Image by Julia Kuo, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Nishta Mehra is a parent, partner, teacher, and writer. Her books include The Pomegranate King and Brown White Black: An American Family at the Intersection of Race, Gender, Sexuality, and Religion. She serves on the board of Just City, a non-profit organization working to build a more humane justice system in Memphis, Tennessee.

Transcript

Lily Percy, host: Hello, fellow movie fans. I’m Lily Percy, and I’ll be your guide this week as I talk with Nishta Mehra about the movie that changed her life, The Namesake. It’s a tearjerker, but don’t worry. We’re gonna be here for you every step of the way.

[music: “The Namesake Opening Titles” by Nitin Sawhney]

There are some movies that teach us something new every time we watch them, and The Namesake is that movie for me. The first time I saw it I was blown away by the raw tenderness of the movie, the way that this story of an immigrant family from India is told with such beauty and grace. And at the time when I saw it, I was in my early 20s, so I was particularly drawn to the character of the teenager, of Gogol, played by Kal Penn, because it most closely mirrored my own experience as a young person judging every part of my parents’ experience in this new country. But now when I watch it, I look with such compassion at the parents at the center of this story and see that this story is actually about them.

[excerpt: The Namesake]

The Namesake tells the story of Ashoke and Ashima, this couple from India who are married in an arranged marriage, and they move to New York to start a new life together. They raise two children in the U.S., and they give their first-born the nickname Gogol, after the Russian writer that Ashoke loves. And Ashoke and Ashima have to make sense of how to relate to their children in this new world.

[excerpt: The Namesake]

[music: “First Day in New York” by Nitin Sawhney]

As Gogol gets older, his relationship with his parents begins to change though. He starts to see things differently — just as we all do with age — and he starts to understand that there’s so much he doesn’t know about their lives, their inner lives, and the reasons why they are who they are. And that becomes especially apparent in his relationship with his father, with Ashoke, played by the wonderful actor Irrfan Khan. And Ashoke ends up being the hero of this movie in so many ways. He’s also the person that Gogol doesn’t really understand until after Ashoke has died.

[excerpt: The Namesake]

The Namesake is a movie that’s divided into two parts — what comes before Ashoke’s death and what comes after Ashoke’s death. And his death really changes his family forever. And that’s something that the writer Nishta Mehra could really relate to. She lost her father only a few months before this movie was released, and the experience of watching it in the theater was both profound and cathartic. And she realized that there were so many things that she had never really seen about her parents that this movie was mirroring to her.

[music: “The Namesake Reprise” by Nitin Sawhney]

Ms. Percy: I’d love to take you back in time for a minute and ask you, where you are, to close your eyes and for ten seconds just be in silence and think about the first time that you saw the movie that we’re gonna talk about today, which is The Namesake. Think about how old you were, where you were, how it made you feel — all of the memories attached to that. And I’ll chime in when the ten seconds are up.

So what memories came up for you?

Nishta Mehra: I remember very distinctly what theater it was and just the space of the room. It’s a theater that no longer exists in Houston, and so there’s that nostalgia piece tied to it, as well. And it was, I think, the only theater that was showing The Namesake at that time. And I was with the woman who’s now my wife, and I think the music started. And music is such a big part of the film, just that constant in the background. And I just burst into tears. [laughs]

Ms. Percy: Wow — just the music.

Ms. Mehra: Just the music. I think for it to be in an American theater — this wasn’t a theater that showed Hindi movies — and there were other people there who didn’t necessarily look like me. There were white people in there. And my partner, Jill, is white, and we were going to see this mainstream movie. And that music was something I had never heard in connection — it was like this merging of worlds. And I just started crying. And I don’t think I really stopped [laughs] for most of the film, because everything, each part of the film and each part of the dynamic and the plot as it unfolded, just felt very familiar to me. And it was like watching my own experience projected on this big screen with this beautiful cinematography and just treated so lovingly, with so much care and attention to detail that it was so moving. And it was that way, too, even just re-watching it now, however many years later — still such a powerful experience.

[excerpt: The Namesake]

Ms. Percy: When I was thinking about the timing of this movie, when it was released, it was really so closely after your father died. And this movie, one of the central pieces of the movie is this death of the father that we watch happen in the character of Ashoke. And I can’t imagine watching this movie and grieving at the same time.

Ms. Mehra: I think it’s sort of a running joke among folks who lose parents, especially those of us who lose parents early, to avoid Disney movies as a rule, because you know a parent is gonna die.

Ms. Percy: So true, and early on. In the first 15 minutes, they’re gonna kill the character.

Ms. Mehra: Oh my gosh, right? And it’s just like, watching Frozen, “Don’t get on that boat. Why are you getting on the boat? Don’t get on the boat.” And so there’s that experience, on the one hand. And then, with this film, I had read the book. I’m a huge Jhumpa Lahiri fan. And so I knew what was gonna happen. I knew, going in. But it’s still so different, right?

I had read the book before my father died, and so then, like you said, to watch this film — I think it had been just over a year since losing my father — it felt like the movie had been made for me. As much as there were differences, obviously, between me and the protagonists and the circumstances — and my family’s not Bengali — but none of that mattered, because the essence of the emotional experience was — and remains — so real.

Ms. Percy: Well, and that’s one of the beautiful things that I don’t quite understand, logically, but I understand in my body, emotionally, is that the more specific you are to your own experience, the more universal it becomes, because their family’s not my family. My family’s also an immigrant family, but it’s from South America. It’s a very different experience. And yet, there are so many things that when I watch this movie, I relate to, and I just think, “That’s my experience too.”

And there was something that you wrote about in your book, Brown, White, and Black — you talked, actually, about the first time you saw Bend It Like Beckham. And I’m just gonna read what you wrote, because it was so beautiful.

You say, “The experience was so moving that I cried. I saw how I missed out on so much of the rich inner lives of my parents and my friends’ parents, because I saw them the same way the white, broader culture did, discounting them because of their accents and otherness. How shameful that I had never considered my own story to be movieworthy, to discover as an adult that the uncles I’d thought were goofy and uncool performed complicated brain surgeries and lectured internationally or to realize that I’d underestimated my gossipy, talkative aunties, only to learn about the multiple degrees held (because American universities wouldn’t accept their ‘foreign’ master’s degrees when they’d immigrated) and the three or four or five languages they spoke.” And then, this is the sentence that stopped me in my tracks. I’m so grateful to you for writing it. “It’s a raw deal to internalize the stereotypes of the very culture that never embraced you fully.”

Ms. Mehra: I think I’m still grappling with that.

[music: “Max Arrives” by Nitin Sawhney]

Ms. Percy: Watching this movie this time, The Namesake, it’s a movie that when I first saw it in my 20s, I so related to Kal Penn’s character, to Gogol, and I was all about his — the first half of the movie is his experience as a teenager and as a young adult in his 20s and where he has this viewpoint that you write about here, of his parents, of his community. It’s kind of embarrassment and a real wanting — a real desire to want to assimilate into white culture. And he changes his name from Gogol to Nikhil, to Nick. And he dates the epitome of white privilege [laughs] in his girlfriend Max and their relationship. And it wasn’t until I watched it this week that I really understood what you’re writing about here, which is the beauty and the honesty that these parents are bringing to their lives and their experience that I just never had the expansive mind to appreciate.

Ms. Mehra: I’m glad to know that that piece rang true for you. Like you said, I think for any first-generation, second-generation kids, or those of us who have that tie to immigrant parents, there is so much commonality, I think, in the experience. And then I think the specificity creates authenticity. So we recognize it as real, that this is a real community that has really built something out of very little and is figuring out what it means to be Indian-American in the ’80s and ’90s. And it’s a territory that lots of us mined when we sort of felt like we were doing it alone. And I think that is part of what is so powerful even when, like you said, the specifics are very different, just to have that connection; you get what that work was like. And you get how you can hold these two sets of feelings that seem really contradictory and to understand how conflicted you can be about your own sense of identity and where you belong. And that’s so reassuring, [laughs] for me.

[excerpt: The Namesake]

Ms. Percy: Something that hit me in a way that just hadn’t hit me before — I’ve seen this movie probably ten times, and yet, every time I watch it, I really see something new. The dedication at the end that Mira Nair has: “For our parents, who gave us everything.” Watching the movie this time around and seeing the journey — we begin in India, with Ashima and Ashoke, and where we end up going through with them — this movie is actually about them. [laughs] It’s not actually about Gogol. And it sounds so obvious to say that, but I never really understood that until watching it for the tenth time, that this is really all about leaving their home, leaving everything they knew, and starting over in America. And it could very well be the standard story of the American Dream — I read the Roger Ebert review for The Namesake, and I was actually really disappointed in the fact that he didn’t get that this movie is about more than just the American Dream, the immigrant American Dream, because it’s not about that, at all. But we see their love story unfold. And we see these tiny moments that make up a life in their life together, before they have kids; and then, once they have kids, and as they grow older.

Ms. Mehra: So much of what you just said was resonant for me and powerful for me. One, just the storyline of these two people who — this is not a typical “romance” that we would see in an American film.

Ms. Percy: A woman who falls in love with a man because she liked his shoes. [laughs] She chooses him because of that.

Ms. Mehra: And they end up — strangers together — moving across the world.

Ms. Percy: They were in an arranged marriage, we should say.

Ms. Mehra: Yes. Figuring each other out, figuring out what it means to be together and falling in love with each other after they’ve already been married, which is very much true to the experience that my parents had. Their marriage was also arranged, and my dad had not yet been abroad, but knew that he wanted to and was very clear — that was, again, one of the questions that came up, would my mom be willing to go? And she was.

My mom always jokes that they got married, had sex, and then fell in love. And she was always like, “Please do it in some other order than that.” [laughs] So I think that it’s so easy, when people are your parents, to not see them with a wide lens. You see them up so close. And so, I’m so grateful to this film to see, like you said, just this arc of this romance; and very different, again, from what we would typically think of as romantic.

At one point, Gogol even says to his girlfriend, Max, “I’ve never even seen my parents really touch.” And my parents were different from that; my dad was actually pretty affectionate. But the romance in the film, I think, comes through, that there are different ways for this to look. And it’s no less beautiful, and it’s no less real, this bond between the two of them. And that’s part of what makes Ashoke’s death so devastating, is because you see how clearly these two people have really grown up together and built their lives around each other and together.

[music: “Farewell Ashoke” by Nitin Sawhney]

[excerpt: The Namesake]

[music: “Shoes to America” by Nitin Sawhney]

Ms. Percy: If you’re enjoying my conversation with Nishta Mehra, consider leaving a review on Apple Podcasts. It really helps people discover This Movie Changed Me, and we also just love hearing what you think. As always, thank you for helping us build our movie-loving empire.

[music: “Shoes to America” by Nitin Sawhney]

Ms. Percy: Let’s talk a little bit about Ashoke, who is just — oh, my God, first of all, played by Irrfan Khan, who is this amazing actor. And I don’t think I’ve ever seen a face that has as much kindness and thoughtfulness in it as he does in this movie.

Ms. Mehra: He’s perfect in the role.

Ms. Percy: He embodies him so well. The thing about Ashoke is, he spends the whole movie kind of having this really deep inner life that he doesn’t reveal to his son. [laughs] And he struggles to, right? Some of the most heartbreaking scenes in the movie are when he’s trying to tell Gogol about the origin of his name, like we see him give him a graduation gift, and we see him try to begin to tell him, but then he stops, because I think he senses that Gogol isn’t ready for it yet. And it’s heartbreaking to watch, because once you’ve seen this movie one time, you know what’s gonna happen. And I’d just love to hear you talk a little bit about that relationship, the relationship between Ashoke and Gogol.

Ms. Mehra: I think that one of the things that was really distinct for me, in watching the film again recently, was just how much is lost in this journey that immigrants make. And I think, so often, we focus on what’s gained. I know that my parents did that — that that was the narrative that they established for me. “We did this for you. We did this to create this kind of life. We did this so that you would have these opportunities.” And my parents do, in very many ways, embody that “American Dream.”

Ms. Percy: But that’s not the full story.

Ms. Mehra: It’s not the full story, and I think as parents they — I don’t know if “shielded” is the right word, but they certainly never really revealed, I think, the extent to which there was loss and there were things that were missing and there were things that they gave up. And it hit me so powerfully, watching the film this time, on so many levels.

And for me, that is a huge piece of just noticing and seeing how much I missed, how much I wasn’t paying attention to that rich inner life of my parents — which, I know, is an inevitable experience, when you’re, certainly, a teenager, and he’s got Pearl Jam playing in the background and doesn’t turn it down.

Ms. Percy: That’s so perfect. [laughs]

Ms. Mehra: It’s just like, “Stop being such a jerk” — but only because I totally recognize that behavior.

Ms. Percy: Same. Same.

Ms. Mehra: Oh, good. I’m glad it’s not just me.

Ms. Percy: This was just the biggest shaming, where I was just like, “Oh, God.” [laughs]

[excerpt: The Namesake]

Ms. Mehra: And that is part of, I think, what is particularly — and I use the word “tragic” in a distinct way, not in the casual way we maybe use it in conversation — but what feels tragic about losing a parent so young is that you still kind of have your head up your butt. You haven’t really gotten to be an adult with them, being an adult, being two adults in the room together. And that’s such a distinct experience. And it takes time to figure out what that dynamic looks like.

And I think that my dad and I had started to do some of that, and it was actually when we were in India. We took a trip, just a few months before he died — he died very suddenly and unexpectedly, so the trip and his death were unrelated; it just worked out that way. But that trip to India is about a thousand times more powerful in my memory of it, and the conversations that we were able to have, and him taking me to his hometown and showing me where he went to school and seeing him in his element. And I think there’s — to a certain extent, it’s very hard to understand someone fully until you really see them in their earliest environment, or — you know how sometimes you meet someone’s parents, and you’re like, “Oh, OK. That explains so many things,” that kind of thing.

Ms. Percy: [laughs] Yes, the same is true for our parents.

Ms. Mehra: Right? Like, he was a kid. It’s, again, so obvious, and you feel so goofy, realizing those things and thinking, “Why didn’t I think about this before?” But I think that’s also true, at least, for me, of the very comfortable and good life that my parents created for me, is that I didn’t have to think about that stuff. And that was what they were proud of. They were proud that they had made a life for me that was so much easier than theirs had been. And that’s that irony of — then, I think, I had some blind spots, because of that.

Ms. Percy: I love that you brought up loss, because one of the things that — one of the scenes that really stood out for me, this time, watching it, was the scene where Ashoke receives a phone call in the middle of the night, and Ashima is sleeping next to him, and it’s the news that her father has died. And they’re in different countries. And he has to give his wife this news. And it never hit me, the idea that when you have to grieve and lose someone and they’re in a whole other country, and the level of loss that that creates, because you can’t be there with them.

Ms. Mehra: And knowing that she hasn’t seen him for this period of time and that she doesn’t go back until after he’s already gone.

Ms. Percy: And the noise that she makes when she finds out — oh, my goodness. I just burst into tears. [laughs]

Ms. Mehra: So primal, I know. And one of my very first memories — again, it feels like this movie was made for me, because one of my earliest memories, I was about four, I think, and there was a phone call, and my father’s father had died. And it was the first time that I had seen my dad just break down. And it was such a powerful experience for me; I think that’s why I remember it, because it was so upsetting. And my mom actually shared that I started to wet the bed — it was just so disruptive for me as a four-year-old because that vision of my dad was so contradictory to how I had always seen him. And now, as someone who has lost a parent, I can look back at that with so much compassion for him — that, like you said, he was so far away from his family; he’d made this set of choices very much designed to support and help his family. He did that classic immigrant thing of sending money home and handling things on behalf of his sisters and taking care of what he could. But again, with that loss, that it means that he wasn’t there with his dad when his dad died. I got to be in the room with my dad when he died, but my dad didn’t get to do that for his dad.

Ms. Percy: And the character of Gogol doesn’t get to do that in The Namesake.

Ms. Mehra: No.

Ms. Percy: One of the things that’s so heartbreaking is, we see Ashoke go to a teaching position in another state for six months, and he ends up suddenly dying there. And none of the family is able to say goodbye properly.

Ms. Mehra: That scene where Gogol comes to the apartment — he’s come to identify the body, perform this oldest-child, representative-of-the-family role …

Ms. Percy: And he tries on his shoes.

Ms. Mehra: … and he tries on the shoes. And then he gets in the bed and sees his father living in this really lonely and aseptic place, which I think compounds the grief and that sense of sadness. But that feeling of stepping into that role and literally stepping into his father’s shoes, even though, as a female, there were parallels that aren’t quite the same — I did not shave my head, for example; I grew my hair out as a way of honoring my father. But that sense of, OK, now I have to be a different kind of way, is, I think, again — for those of us who have experienced that kind of loss at a relatively young age — you know what that feels like. And I remember distinctly, looking into the faces of my aunties and uncles — who were, of course, of tremendous support in the wake of my dad’s death, just like it happens in the film — I could see them looking at me differently, and that’s how I knew that the role had shifted, and I was somehow more of an adult than I had been before.

[excerpt: The Namesake]

[music: “Farewell Ashoke” by Nitin Sawhney]

Ms. Percy: One of the things I love about The Namesake is that every time I’ve seen it, it’s given me something new, and I learned something new about myself and the world. Watching it this time, with you in mind, I kept wondering how this movie has informed you as a parent, because you’re now a parent yourself.

Ms. Mehra: I am.

Ms. Percy: I’m just so curious to know, when you watch this movie now, how you see it differently as a parent.

Ms. Mehra: That’s a great question. Right; because that experience is another one that is going to change you. [laughs] You don’t know how, necessarily, but you know you’re going to be different, and there’s no going back. And as a parent, I have an almost-seven-year-old — she would want me to say “almost-seven,” instead of six, because it sounds way cooler — an almost-seven-year-old named Shiv.

And I think one of the things I’ve been really conscious of and sort of amazed by, honestly, is, it’s been important to me to show as much of my full self as is appropriate, to my child, because I’m so aware of, I think, a lot of the things I missed about my parents in their attempts to shield me from things. So Shiv has seen me many times be very sad when I’m thinking about my dad or on his birthday or on Father’s Day or things like that. And she’s aware of what that is. She has a sense of what that means, to miss, as she would call him, nanaji, which is mother’s father. And I am amazed by how, for an almost-seven-year-old, she has such an intuitive way of responding to and empathizing with that. For her, as someone who was adopted at birth, there’s a sense of loss there, as well; of her birth mother, in particular. And the way that she can navigate empathizing with me and not being so scared of me being sad, it’s part of our life experience together that sometimes mom is sad about this, and sometimes I’m sad about this, and then sometimes we are dancing around to Beyoncé. And all of it is a part of a fully lived life.

And that’s really important to me, for her not to be afraid of what she feels or of what other people feel and to make room for it. And I think that’s something that I really try to hold onto and, in watching the film again, was reminded of, the importance of trying to let her see me as a human who has got a whole range of feelings and is flawed [laughs] and also who has a history before her, as well as with her.

[music: “The Namesake Opening Titles” by Nitin Sawhney]

Ms. Percy: Nishta Mehra is a parent, partner, teacher, and writer. Her books include The Pomegranate King and Brown White Black: An American Family at the Intersection of Race, Gender, Sexuality, and Religion. She also serves on the board of Just City, a non-profit working to build a more humane justice system in Memphis, Tennessee. On December 8th of this year, Nishta’s parents would have celebrated their 52nd anniversary. We thank them for bringing Nishta to this world.

Fox Searchlight, Mirabai Films, Cine Mosaic, Entertainment Farm, and UTV Motion Pictures produced The Namesake, and the clips you heard in this episode are credited entirely to them. Fox Music and Rounder Records released its soundtrack, and Nitin Sawhney scored the movie.

Next week, we have a This Movie Changed Me double feature to cap off our second season. Entrepreneur and wise man Seth Godin will speak about his love for The Wizard of Oz. And in a separate conversation, I’ll talk about The Wiz with the Obama Foundation’s chief engagement officer, Michael Strautmanis. The movie’s a modern retelling of The Wizard of Oz starring Lena Horne, Richard Pryor, and the one and only Diana Ross.

The team behind This Movie Changed Me is: Maia Tarrell, Chris Heagle, Tony Liu, Kristin Lin, Marie Sambilay, and Lilian Vo.

This podcast is produced by On Being Studios, which is located on Dakota Land. We also produce other podcasts you might enjoy, like On Being with Krista Tippett and Becoming Wise — find those wherever you like to listen or visit us at onbeing.org to find out more.

I’m Lily Percy. Being a teenager is complicated, but so is being a parent, so let’s all just try and remember that.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.