‘This Movie Changed Me’ Is Back

Movies can be whimsical, terrifying, life-altering, culture-changing experiences where the big ideas we take up at On Being show up in the heart of our lives. This hour we experience this through seven lives and seven movies — from The Wizard of Oz and Black Panther to The Exorcist. Get out the popcorn for this upcoming flavor of the new season of our On Being Studios podcast This Movie Changed Me — a love letter to movies and their power to teach, connect, and transform us.

Image by Julia Kuo, © All Rights Reserved.

Guests

Naomi Alderman is a professor of creative writing at Bath Spa University. Her books include The Power and Disobedience, which was adapted into a feature film starring Rachel Weisz and Rachel McAdams. She's also a game writer whose work includes the alternate reality game, “Perplex City,” and the fitness game, “Zombies, Run!”

Drew Hammond is an English teacher at Eagan High School in Eagan, Minnesota. He’s also an award-winning public speaking coach, a published playwright, and a former stand-up comedian. He is featured in the documentary Figures of Speech, which is out on Netflix.

Mark Kermode is the chief film critic for The Observer, host of the podcast Kermode On Film, and co-host of Kermode & Mayo's Film Review on BBC Radio 5 Live. His books on film include Hatchet Job, It’s Only A Movie, and How Does It Feel? A Life of Musical Misadventures.

Zahida Sherman is the director of the Multicultural Resource Center at Oberlin College. She was formerly the assistant director of black student success at University of the Pacific. Find her writings on race, gender, and adulthood in Bustle and Blavity.

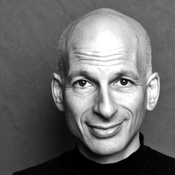

Seth Godin writes the wildly popular daily, Seth’s Blog. His podcast is Akimbo. He’s the author of many best-selling books, online and in print, including This is Marketing, Purple Cow, The Dip, and Linchpin. In 2018 he was inducted into the Marketing Hall of Fame.

Michael Strautmanis is a lawyer and the chief engagement officer at the Obama Foundation. He served in both the Obama and Clinton administrations and at one time worked for The Walt Disney Company, where he specialized in corporate citizenship.

Monica Castillo is a writer, film critic, and the president of the National Association For Hispanic Journalists’ New York City chapter. She has written for The Washington Post, The New York Times, Cherry Picks, and Remezcla. Her newsletter is “Save Your Ticket Stub.”

Transcript

Krista Tippett, host: Movies can be whimsical, terrifying, life-altering, culture-changing experiences where the big ideas we take up at On Being show up in the heart of our lives. This hour we experience this through seven lives and seven movies — from The Wizard of Oz to Black Panther and even, I can’t believe I’m saying this, The Exorcist. So get out the popcorn for this upcoming flavor of the new season of our On Being Studios podcast, This Movie Changed Me — a love letter to movies and their power to change life and culture.

[music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoë Keating]

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. This Movie Changed Me is hosted by our very own movie-loving executive producer Lily Percy, who will also walk us through this hour.

[music: “I Got You Babe” by Sonny & Cher]

Lily Percy: Groundhog Day centers around Phil Connors — this grumpy, cynical weatherman played by Bill Murray who finds himself stuck in a time loop that no one else is aware of, living the same day over and over again, waking up every morning to the same song.

[excerpt: Groundhog Day]

As the movie unfolds, Phil slowly goes from being confused to angry, to self-absorbed, and depressed, before finally accepting his situation and the people around him. Chances are that if you’re a Bill Murray fan or you grew up in the ’90s, you’ve seen Groundhog Day. But I guarantee you that you’ve never looked at this movie the way that writer Naomi Alderman does. She wrote the highly buzzed about novel The Power. And Naomi says that, even though on the surface Groundhog Day is a comedy, she also sees layers and layers of depth — and practical, transformative life lessons.

Ms. Percy: Roger Ebert, when he reviewed this movie for the second time, so 2005, years later. I don’t know if you’ve read that review, but he says this beautiful, beautiful — just beautiful words around Phil. He says, “Phil undergoes his transformation but never loses his edge. He becomes a better Phil, not a different Phil … Tomorrow will come, and whether or not it is always Feb. 2, all we can do about it is be the best person we know how to be. The good news is that we can learn to be better people. There is a moment when Phil tells Rita, ‘When you stand in the snow, you look like an angel.’ The point is not that he has come to love Rita. It is that he has learned to see the angel.”

Naomi Alderman: Yes, oh, that is gorgeous.

Ms. Percy: Roger Ebert, prophet.

Ms. Alderman: Prophet, prophet. Testify. And he continues to be a little bit selfish, which I love.

Ms. Percy: Exactly — this is a realistic portrayal of a man, of a human being.

Ms. Alderman: Yeah. Watching it again, I was particularly struck by the way that he isn’t a monster at the start, and he’s not an angel at the end. It’s a realistic softening of someone who kind of always knew. It’s about a midlife crisis. It’s about what it means to be a good person; about what it means to try to help; about what it means to always be growing.

And you couldn’t — the movie never answers how this happened to him, which is wonderful. One thing you could suggest is that in that moment, he realizes that he’s gonna have to fix something and that this thing that happens to him is something that he needed. He wanted it; he called to it; he asked for it, maybe. That’s a thought that I had about it, whilst watching it. Can I also talk about — you know the title of the thing, of the podcast is about a movie that changed your life? So I saw this when I was 18. I must’ve watched it at least once a year since then, so that’s at least 25 times — and perhaps more. I feel like there were times when I was watching it more than once a year because I felt like it had some answers for me about what constituted a good life.

Ms. Percy: So how was watching it those 25 times, then? Every time, do you find new answers for yourself? How does it come into your life?

Ms. Alderman: It’s interesting — I feel like, maybe, now I have started to find the edges of it. In terms of, well, if I believe this, then what is really worth doing with my life? What is worth doing is stuff that somehow works on myself, my inner self, whether that’s by psychotherapy or learning new skills or reading great books or improving my sensitivity towards the world; or, that it’s trying to help.

There’s a thing that I do sometimes. It sounds weird, but it’s sort of a spiritual practice. Every now and then, when I feel like I have either been through some hard times or that I’ve somehow become a little bit too blasé about my life, I spend a month, every single day, going to a place that I have not been before. And you can do this while traveling, obviously. But it is much more effective if you do it very, very close to where you live; so, things that are within half an hour of where you live. In other words, you could always have gone there, but you just never bothered to get off your beaten track. You’ve never ever gone to have a look in that tiny little weird art gallery that you pass by every day on your walk to work. You’ve never gone to sit in that park. You’ve never gone to be in that church. You’ve never tried out the baguette from that café.

Sometimes I do this every day for a month, just — literally, it can be five minutes, pop in. But suddenly, I have a sense of the incredible richness around me, of things that I have seen but not really noticed. And at some point in that month, what happens is, I receive “the benediction” — that’s what I call it — which is, at some moment, I will suddenly become aware of the incredible beauty and richness of everything around me. So, I would look at a brick wall and suddenly be completely struck by the difference and the there-ness, the this-ness, of every single brick in that wall and how much has gone into just even creating that single wall, and then, look, someone’s put windows in there. And look at the plants. There’s a little bee that just buzzed past me. And when you look at the world that way, when you look at the world with Phil Connors’s eyes, when you go right through the sense of ennui, through the despair, right through to the other side, and all you can see is how amazing it is to just be allowed to be alive right now.

[excerpt: Groundhog Day]

[music: “I Believe Her” by Alan Silvestri]

Ms. Percy: The first time that I saw Contact I was blown away. I had never seen a movie that described all the questions and all of the mysteries I felt around God and science and, even love. Contact is adapted from the novel by the scientist Carl Sagan, and it tells the story of Ellie, played by Jodie Foster. She’s an astronomer who works for SETI, an organization trying to find life on other planets.

Many people in the science community don’t take her work seriously because it’s the kind of science you can’t prove. But Palmer Joss — this kind of spiritual pastor, new-agey seeker, played by Matthew McConaughey — understands what Ellie is going through. The relationship between Ellie and Palmer is so important because it illustrates the divide and parallels between science and faith. And this is something that my next guest, high school teacher Drew Hammond, felt deeply when he was a teenager, and continues to shape how he interacts with his own teenage students.

Drew Hammond: It feels very much like a depiction of all the things that I was struggling with when I was a teenager, which was, how come I feel alone a lot? And how come I can’t feel the things that other people seem to be feeling, at ease? How come I don’t have that same kind of peace that people that go to church on a regular basis feel? And how come I can’t feel that connection that everybody else feels to something? And so, I think the story of somebody exploring their own atheism is — that’s a hard story to tell, in a lot of ways, and it’s also just not a super-common story to tell. And so, seeing her and her strength and her convictions about what she believes — that was one thing.

But then, the other part was that — this idea that we can search for questions, and as long as we are continuing to search for questions, it doesn’t matter what the questions are. The answers are secondary. They’re just not as important as the fact that we are searching. And so, when I saw the movie — I saw it at the absolute perfect age. I think I saw it when I was 18. And I got permission to just know that the search was enough and that I don’t have to believe anything that anybody is telling me, which, when you’re a teenager, is the greatest permission …

Ms. Percy: Yes, it really is.

Mr. Hammond: … and that I also will probably spend my life changing what I believe, and as long as I stay curious and as long as I stay active in questioning, then I’ll be OK.

And I think that’s what you see, is — you see Jodie Foster — over however much time in the movie, you see her character changing what she believes and, ultimately, being better for it.

[excerpt: Contact]

Ms. Percy: As you’ve gotten older and continued to watch this movie — because, much like myself, I know, you watch it over and over again …

Mr. Hammond: About once a year.

Ms. Percy: [laughs] … What do you continue to learn from it? What are you learning, as you grow together with the movie?

Mr. Hammond: As a teacher, one of the challenges I have is that I have to allow kids to enter the classroom, bringing whatever it is they’ve brought with them. And so, I have kids that believe radically different things than I believe and that think about some pretty important things very differently. And I cannot think that something is wrong with them, because they grew up with a different set of experiences.

And that’s been one of the hardest things for me as a teacher to wrap my head around, is that all I can do is give them the space to ask questions and to know that those questions are valid and try and encourage them, as much as possible, to question everything that they believe, knowing that if it’s good, they’ll come back to it. And if it’s not, then they’ll find something better.

In some ways, that is an incredibly frustrating thought — that we might just not ever know — but if we just embrace that as “That’s what the journey looks like,” that we will just always be surrounded by questions, then, what a cool gift that is, to know that there may be things that happen in our lifetimes that we cannot possibly foresee. We might get a message from an alien race …

Ms. Percy: Using math. [laughs]

Mr. Hammond: … Right, that might change everything we know about ourselves. And how great would that be? How cool would that be, if that all of a sudden happened that all the world had to totally rethink everything that we know?

[music: “End Credits” by Alan Silvestri]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, This Movie Changed Me is back.

[music: “Night of the Electric Insects” by Jack Nitzsche]

Ms. Percy: Before I saw The Exorcist, everything I had read or heard about this movie over the years was about how shocking and scary it was. But no one ever told me how good it was — and if you haven’t seen it, you might be as surprised as I was to discover that it truly is a masterpiece in movie making.

The Exorcist takes place in Georgetown in Washington, D.C. and tells the story of a twelve year old girl and her demonic possession. But the true horror comes in watching her mother attempt to help her — she goes to doctors, psychiatrists, before finally turning to the Catholic Church as a last resort.

Movie critic Mark Kermode is, for me, the only person that holds a candle to Roger Ebert. He hosts the podcast Kermode on Film and also co-hosts Kermode and Mayo’s Film Review from the BBC — one of my favorite podcasts — and is really the foremost expert on The Exorcist. He’s made documentaries about it; he’s written about it; and he even became friends with the director, William Friedkin, and the screenwriter, William Peter Blatty. Mark was too young to watch the movie when it was first released, and he spent 6 years obsessing about it before finally seeing it at the cinema.

Ms. Percy: So I have to ask, what toll does that take on you as a kid, and also, how do your parents react to watching you obsess in this way? Did they say, “You can’t see this”? I believe you grew up Anglican, if I’m not mistaken.

Mark Kermode: Yeah — I was brought up as a Methodist, and then I’m Anglican now because — well, I’m C of E now, which is Anglican. There’s a joke about the Church of England, which is, “You don’t lose your faith. You just can’t remember where you left it.” So my parents knew that cinema was the thing that I was interested in. But they also knew that I was really, really interested in horror. And when the horror thing began, I’d come downstairs at night and watch old Hammer reruns on our black-and-white television, with the volume turned down so that my mum and dad couldn’t hear. And they weren’t down on it in any way. So I think what they thought was, if you’re interested in anything, that’s a good thing.

And I’ve always said this — there’s a great vilification of horror movies. “Oh, they’re bad for kids,” or “They do terrible things.” If you are a slightly lonely child, horror movies, they do speak to you. And I’ve met so many people over the years — because I’ve spent a lot of time working in the field of horror films — who have that same thing. They either work for you, or they don’t. And if they don’t, you can’t explain it. It’s like if somebody says, “What do you think of opera?” I go, well, to me, opera is — I can appreciate it, but I don’t “get” the thing.

Ms. Percy: Yeah, it doesn’t speak to you.

Mr. Kermode: And it’s the same with horror movies. The difference is, no one tells you that if you listen to opera, you’re gonna turn into a serial killer. So if you were a bit of an outsider, horror movies were like your friends.

Ms. Percy: I love the way — and I have to say, I’m such a huge fan of your writing, so I will be quoting you back to yourself a lot. I hope you’re comfortable with it.

Mr. Kermode: Thank you. As my wife once said, I don’t fish for compliments, I troll for them.

Ms. Percy: [laughs] I love that. Well, I have been, I confess, a person who has never really given horror its due. And reading you write about it, there’s this wonderful way that you say, “People talk endlessly about the damaging effects of horror movies, but too little is heard about the life-affirming power of being scared out of your mind, and in those very rare cases, out of your body. You ask me if I think there is more to this world than the grim realities of aging, disease, and death, of mourning and loss, and I will refer you to that first viewing of The Exorcist, during which my imagination took flight, my soul did somersaults, and the physical world melted away into nothingness around me. I don’t think that there’s a spiritual element to human life. I know it, because I have experienced it firsthand, and I have horror movies to thank for that blessing.”

I love that.

Mr. Kermode: Thank you.

Ms. Percy: Tell me a little bit more about that experience, what you’re talking about, that aliveness, that presence that you had, being taken away by The Exorcist.

Mr. Kermode: That experience — years later, I would talk to Bill Blatty, who wrote The Exorcist, and Bill had some sort of conflicts about how the film was received, what the film meant to people. He was very concerned that, because certain key sequences had been taken out of it, that the message of it wasn’t clear. And the message, from his point of view, was very clear. It is, it will all be all right in the end. God is in his heaven; there are angels, because there are demons — you know, if there are demons, then there are angels. And he was very, very clear about it. And Bill was a very religious man, and that was what the story was about, for him.

But he said — we were talking quite candidly at one point, and he said, “The thing is, when you watch that film, you are alive. You are having an experience. And whether that experience is good or bad, you are alive, and you are aware of it.” And what it means is that there is a thing that horror movies can do — and to some extent this goes into roller coasters, all that sort of stuff — it makes you alive by confronting you with the spectacle of something else.

But it’s more than just, oh, you’re experiencing something dangerous in a safe environment; it is, in the genuine sense of the word, transcendent. Now, from my point of view, that kind of almost out-of-body experience that I had watching The Exorcist was wholly positive — wholly positive, because it was a form of transcendence. And there are moments when cinema does that to you, and it doesn’t matter whether it’s a horror movie or whether it’s a love story or whether it’s a thriller or science fiction — it’s something that makes you think there is more to this world than this chair that I’m sitting in and this auditorium that I’m sitting in.

Years later, I went to Georgetown, and I walked up those steps. And I walked to the front of where the house should be — obviously, it’s different in real life. And again, it was that incredible feeling of, I’m walking into something that I’ve already been into. And that déja vu — that is an uncanny experience, and uncanny experiences tell you that there’s more to life than just this.

[music: “Wakanda” by Ludwig Göransson]

Ms. Percy: I enjoy Marvel superhero movies, but I admit that I don’t expect a lot from them. But Black Panther changed all of that. It tells the story of Wakanda, an African country unlike any other, with advanced technology, rich and abundant resources — a black nation that is powerful and thriving, with characters that embody the complexity of black identity, something that we rarely see at the movies.

These layers really spoke to Zahida Sherman when she saw Black Panther. Zahida works with college students, and when the movie premiered, she took them to go see it. Watching Black Panther with her students, she genuinely felt Wakanda welcoming them with open arms.

Ms. Percy: What was the experience, actually being in the theater, watching it after all that anticipation?

Zahida Sherman: You know, if I tell somebody, “You gotta come through looking like Black Excellence,” I’m gonna take it super serious. [laughs] So I had been planning my outfit for some time. My deceased grandmother, she was super into fur coats. And so I’m rocking this floor-length mink coat — very reminiscent of Coming to America — and I’ve got a huge necklace on, and I got my fro picked out. And so the students see me come in, and they’re cheering me on and really amping me up. [laughs]

Ms. Percy: Oh, I love that.

Ms. Sherman: So there was that, which was hilarious. But then, just sitting in the theater seat and turning around, turning left and right — panning all the way around and realizing, that theater had to be 99 percent black viewers…

Ms. Percy: Which is amazing.

Ms. Sherman: … which doesn’t happen a whole lot, right? [laughs] So, that in itself was incredible; incredible, because I think when you’re a person of color, just in general, and when you’re black, specifically, what happens is, you’re very conscious of the white gaze on you. You’re very conscious of how white folks are perceiving you and what they’re gonna do with that perception, whether it’s they’re gonna weaponize it or they’re gonna — you know, I don’t know; there’s a whole myriad of possibilities, right? But the feeling of that absence was complete freedom, I would say, just to be yourself. And whatever reaction you had — if you laughed too loud, it’s cool; you know why? Because there’s a theater full of black folks who would expect nothing less.

Ms. Percy: Yeah, and one of the things you talk about is what you wanted for your students that night. You write about it so beautifully. You say, “I wanted my students to feel the elation of Black possibility and freedom. I wanted my students to experience the sheer joy of seeing a movie for us and by us, all about what happens when Black life thrives without exploitation and colonization. I wanted my students to see what happens when Black thought, innovation, and beauty are the standards.” That’s so beautiful.

Ms. Sherman: Yeah, thank you. I meant that. And as a side note, [laughs] this is probably the only article I’ve written, or the only piece I’ve ever written that this emotionally — it was tough. I was crying, writing some parts of that, because the things that my students shared with me about their lives and about being black and the struggle of expressing themselves and being themselves comfortably, and all of the shots that come out at them on a macro and micro level, it’s crazy. It’s heartbreaking. It breaks people down. So, to have that experience with them, just to see what it looks like when you’re free — when you’re carefree in your blackness, or just when you’re yourself, in your blackness — that was really important to me, because those students in particular — and that’s not uncommon for a lot of schools in California — they’re like super-minorities, three percent of a whole student body population. It’s crazy. So I think my students, they have that desire and they want to learn more, and they want to grow into whoever they’re going to become as black people, but there are so many barriers that prevent them from being able to do that in their lives. So it was pretty tough, but I just wanted them to, for one night, [laughs] for two hours, 14 minutes, enjoy the film and whatever it does for you — whatever it does for you, spiritually; whatever it does for you, intellectually; whatever it does for you, creatively, let that seed be nurtured into whatever it can become. That was really important to me.

[music: “Spaceship Bugatti” by Ludwig Göransson]

Ms. Tippett: You can hear wonderful longer versions of all the conversations in this hour in season 2 of On Being Studios’ podcast, This Movie Changed Me, wherever podcasts are found. You can also of course listen again to this and all of the shows from On Being Studios at onbeing.org.

Coming up, Seth Godin on The Wizard of Oz, Michael Strautmanis on The Wiz, and Monica Castillo on Coco.

I’m Krista Tippett. On Being continues in a moment.

I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, a new round of This Movie Changed Me — the special power of movies to change lives and transform culture.

[music: “Over the Rainbow” by Judy Garland]

Ms. Percy: The Wizard of Oz is an iconic American movie, and according to the Library of Congress, the most watched movie in movie history. But in case you’ve never seen it, here’s a quick refresher: A tornado hits a farmhouse somewhere in Kansas and transports Dorothy and her dog Toto to the magical land of Oz. There she meets good and bad witches, a scarecrow, a tin man, and a cowardly lion. And she must find her way home by following the yellow brick road to the great Wizard of Oz, who rules all over the land. It sounds like a storybook fairytale, but there’s so much more underneath, as the wise entrepreneur, author, and blogger Seth Godin knows.

Ms. Percy: Roger Ebert is a film hero of mine, and I was reading his review of The Wizard of Oz, and he had so many beautifully perceptive things to say about it. He framed it in a way that I never thought about. He says here that there are “elements in The Wizard of Oz powerfully fill a void that exists inside many children. For kids of a certain age, home is everything, the center of the world. But over the rainbow, dimly guessed at, is the wide earth, fascinating and terrifying.” And I just wondered, when you were a kid, what did you first perceive about that movie?

Seth Godin: For me, it’s always been about the instigation — that Dorothy was, perhaps, the only genuine, independent, young woman heroine in movies, for decades and decades.

Ms. Percy: You’ve talked about how there’s never been a teenage girl like her — right? — in film, in that way.

Mr. Godin: Yeah, treated without misogyny, without sexualization, here is this person who is a hero. And the thing about it is, except for her accidentally killing both witches, everything else that happens in the movie happens because Dorothy instigates. She says, let’s go, come on, let’s go. He can help; we can go there. And that idea — that a young person can take action — is extraordinary. And the way that it was juxtaposed with the vaudeville stuff, with the fantasy stuff, with the Munchkin stuff, made it feel safer, because it wasn’t somebody taking action in your school or your playground. It was someone taking action in this idealized world. But what I took away, the biggest thing I took away, is, it’s up to us. And we could do it if we wanted to.

[excerpt: The Wizard of Oz]

Ms. Percy: Yeah, Ebert says, in his review, later on — I’m just thinking about this as you were talking, that — “They’re touching on the key lesson of childhood, which is that someday the child will not be a child, that home will no longer exist, that adults will be no help because now the child is an adult and must face the challenges of life alone. But that you can ask friends to help you. And that even the Wizard of Oz is only human and has problems of his own.”

Mr. Godin: Wow. There’s so much to dissect here. The idea that the wizard was a con man, but a con man with a golden heart, is another great juxtaposition. “Humbug” was a term that people used to use a lot in the P.T. Barnum days, and it was the idea that somebody was not only a fraud, but gleeful about it; that when you went to see a P.T. Barnum show, you knew there wasn’t really a mermaid in the other room, and you were paying, knowing that you were gonna get fooled, and getting fooled was part of the deal.

Ms. Percy: But it’s interesting, because when she finds out that she’s been fooled by the wizard, it — she’s not angry. I also — that struck me, watching it again this week, was that she’s very kind, and actually, their interactions are very kind.

Mr. Godin: Kansas life, in those days — never having lived there and never been there, then — “Oh, your dog misbehaved? We’re gonna kill him. Oh, the house got blown over by a tornado? Well, we’ll just have to recover.”

Ms. Percy: Yeah. [laughs] Because life was hard.

Mr. Godin: Life was really hard, and I think that Dorothy’s lack of bitterness throughout the entire movie, except when she’s trying to protect Toto — again, gets under our skin.

Now, there are a couple of bits of background — because I’m a marketer who looks at culture — that I think need to be mentioned, because the creation myth here is essential. So when the movie came out, it was trying to chase after Snow White, which was the most successful movie ever made, at the time. And 14 different people worked on the screenplay.

Ms. Percy: That was crazy. When I read that, I was like, oh, my God — how did this even get made?

Mr. Godin: Exactly. Five different people worked on directing it. The first director got pulled to go make Gone with the Wind. [Editor’s note: The movie’s primary director, Victor Fleming, left set early to direct Gone with the Wind. Fleming was the fifth director to work on The Wizard of Oz, and there were a total of six directors who worked on the movie. Learn more.]

It was a complete accident that this movie even got made. And when it came out, except for The New York Times, almost every critic hated it — hated it. And so what we learn here is that you can create an act of genius without being a genius, and that the critics are usually wrong; and that the cultural aspect of — we saw it in this new space, on TV, where it was optimized to make an impact.

Again, there could only have been one movie that pulled that off, and it happened to have been The Wizard of Oz. But what is so cool is that you can whistle a couple notes or bring up a line from it, and the other people you’re talking to will instantly know what you’re talking about. And that’s what makes a culture a culture.

[music: “We’re Off to See the Wizard” by Judy Garland, Ray Bolger, Buddy Ebsen, Bert Lahr]

[excerpt: The Wiz]

[music: “Home” by Diana Ross]

Ms. Percy: The Wiz is a movie that I had actually never seen until I spoke with our next guest, Michael Strautmanis, a lawyer who worked in President Obama’s administration and is currently the Chief Engagement Officer for the Obama Foundation. I knew that The Wiz was a re-telling of The Wizard of Oz story, that it starred Diana Ross as Dorothy, that it featured original music as well as celebrities like Michael Jackson, Lena Horne, and Richord Pryor — and that was kind of it. So watching it was a revelation, not just for the music, which is fabulous — but because, in The Wiz, Dorothy is a 24-year-old Harlem school teacher who gets caught in the middle of a violent storm and is transported to a magical, alternative version of 1970s New York.

When Michael Strautmanis saw The Wiz for the first time at the movie theater, he was also amazed. Dorothy was part of a family like his, lived in a neighborhood like his, and as a young black boy growing up in the South Side of Chicago, watching all of his icons on screen in this way made him feel seen.

Ms. Percy: Watching it for the first time, I was struck, first of all, with how perfect it begins. It begins with a Thanksgiving dinner where everyone’s coming together. And what a beautiful way to introduce this whole story. In a lot of ways, it felt a lot more familiar to me than the way The Wizard of Oz actually begins, with Dorothy — the old version…

Michael Strautmanis: Right — out on the farm. Right.

Ms. Percy: Yeah. This one — it just felt like home. It feels like you’re establishing who this person is, who this Dorothy is. And you really get a sense of her, and this Diana Ross character.

And the other thing that really just blew me away was blackness. Every actor is black. And it’s amazing.

Mr. Strautmanis: Well, I mean, it’s peak blackness. And I know people say that these days — in the era of Black Panther, it’s hard to remember that we’ve been here before. And I was ten, so I wasn’t gonna go see Shaft or Superfly, but I could go see The Wiz. It’s Motown. It’s Berry Gordy. It’s Michael Jackson. It’s Diana Ross. Every actor, as you said, in that movie is black.

And when I was a kid, and even as I’ve seen the movie over the years, it really is so much about that Thanksgiving dinner that the movie begins with, because it just does feel comfortable. It does feel like home. And it was so much of what life was like then. That’s what our Thanksgiving dinners were like. Every family member is represented in there. There’s the young kids, the new baby, the old folks playing checkers and arguing with each other.

And that’s that black experience that I remember and that I would never see on TV or in the movies. And so, to go to the movies and just to see yourself and your life reflected on-screen, I just think it happens too rarely; and particularly, then, it happened too rarely for black folks. And so when it happened, it was big.

Ms. Percy: Well, one of my favorite scenes in the movie actually comes toward the end, when the Scarecrow and the Lion and the Tin Man, they’ve all realized that they had everything they needed all along. And Diana Ross is talking to Richard Pryor, who plays the Wiz — I was like, oh, my God — Richard Pryor?

Mr. Strautmanis: I mean, come on. When Richard Pryor — when you see his big eyes come up from —

Ms. Percy: Crying — when he’s crying, at the end? It’s like, oh, my God.

Mr. Strautmanis: There’s a super amount of crying in The Wiz. The Tin Man makes people well from crying. [laughs]

Ms. Percy: Oh, for sure. But he has a really thoughtful sequence with her, where he says to her — because he’s looking at these three characters, the Scarecrow, the Lion, and the Tin Man, and they’ve been healed in many ways. And so, he’s like, “Can you do something for me?” And she has that great speech where she said that they’ve had what they’ve been searching for in them all along. “I don’t know what’s in you. You’ll have to find that out for yourself.”

Mr. Strautmanis: It really was beautiful. And I also think, there’s something that that whole arc evokes in the black community. There are a lot of folks in my family who I grew up with on the South Side of Chicago, who have never left the South Side of Chicago, because, as we’ve seen in viral videos and on news screens, the world can be a really dangerous place. And there’s so much about neighborhoods like Harlem, other places, where there’s such a rich, vibrant African-American community that you just feel safe. I remember, her mom said, “You’ve never been south of 125th Street.” And there are people who grow up in the South Side of Chicago and never been downtown, never been to the lakefront. And I think that part of what this movie is saying, and part of what I think they found in the story of The Wizard of Oz and in Dorothy is this sense of, you know, there’s a bigger world out there, and it needs to see you, and that there’s more out there for you than what’s around. And, by the way, you can always come home.

Ms. Percy: Exactly.

[excerpt: The Wiz]

[music: “A Brand New Day” by Diana Ross, Michael Jackson, Nipsey Russell, et al.]

Ms. Tippett: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being. Today, This Movie Changed Me is back.

[music: “Remember Me (Ernesto de la Cruz)” by Benjamin Bratt]

Ms. Percy: When I first learned about the Mexican holiday, El Dia de Los Muertos, the Day of the Dead, I was so envious that Mexicans had this tradition of remembrance — of remembering their ancestors and the family members who have long died and who still live on in their memories. And yet the Day of the Dead was something that I never really understood until I saw Coco and saw the joy and celebration and the very lack of death in it.

Coco tells the story of a young Mexican boy named Miguel who loves music. And yet music is the one thing that his family has forbidden him from doing because his great-great grandfather was a musician who abandoned their family. But Miguel wants to enter a music contest for celebrations around El Dia de Los Muertos — so he ends up stealing a guitar that hangs over a legendary musician’s grave. What Miguel doesn’t know, though, is that by using this guitar, he’s going to be transported to a different realm, the Land of the Dead. And this is where his adventure begins — where he must connect to his ancestors in order to return back home. For Cuban-American movie critic and writer Monica Castillo, Coco is an important reminder that we must never forget the generations that came before us.

Ms. Percy: Well, I’d love to take you back in time for a minute by asking you to close your eyes for about ten seconds, and I’ll just prompt you when it’s time to come back from this time travel, to think about the first time you saw Coco. Think about where you were, who you were with, and how it made you feel. And I’ll just chime in when the ten seconds are up.

So what memories came up for you?

Monica Castillo: It’s funny. When I was re-watching it, I also got a flashback to the first time I saw it. I saw it at a press screening, as many critics and reporters will do. A friend of mine brought me as her plus-one. And I remember my eyes welling up, actually, when the mariachi version of the Disney theme started.

Ms. Percy: Yes.

Ms. Castillo: That’s how already-emotional I was.

[music: “When You Wish Upon a Star (Mariachi version)”]

I also knew how rare this was. I’m a big Disney buff, as well. I grew up outside of Disneyworld. There’s no escaping Disney from central Florida. And I just knew that we didn’t have a lot of — maybe I couldn’t use the word “representation,” and I didn’t know how to exactly verbalize it, but I knew there was no one like my family in the Disney canon. And this one, it’s just, here we are in Mexico. It’s not an outsider’s perspective looking in; it is the perspective.

Ms. Percy: And it’s vibrant. It’s alive, and it’s joyous. I think that’s one of the first things that strikes me — as you mentioned, from the opening credits — is, this is not a stereotype.

Ms. Castillo: Right. I don’t feel, at any point, that we were the butt of the jokes; that this was also very welcoming, even though I’m not Mexican-American, and I’m not Mexican, but I could access and see commonalities. I could relate. The use of Spanglish in the movie feels very natural. It doesn’t — I don’t know if you have this problem, but as someone who’s bilingual, so many movies will have the word in Spanish and then will translate it in English immediately afterwards. And I’m like, “So you just repeated yourself. That’s weird. That’s not how we use that.” [laughs]

Ms. Percy: Exactly. Nope. [laughs]

Ms. Castillo: So it was nice to see and watch a movie where they get that right. The characters are pronouncing things correctly. It doesn’t feel forced.

Ms. Percy: Well, and also that they’re casting actual Mexicans, [laughs] which…

Ms. Castillo: That helped a lot. [laughs]

[excerpt: Coco]

Ms. Percy: The first time that I saw Coco, I went to see it with my friend Eddie, who’s Mexican-American. And he’s talked a lot about that, for him, the movie represents this idea that we need to be remembered in order to exist. And watching the movie, I started thinking about a lot of the things that you talked about, the grandparents that are in Colombia that I didn’t really know, because they weren’t in this country, and then the grandparents that I just didn’t make as much of an effort as I could’ve, because the relationship was by phone, and all of these ancestors that make us who we are, who, if you don’t remember, it’s like they don’t exist. It’s such an impactful message that, when I think about it, it makes me feel very sad.

But what I love about Coco is that it turns it around to also make you remember that it’s not too late. Right?

Ms. Castillo: Right. Right. So at the end, when Miguel runs back from the afterlife and is trying to get Mama Coco to remember her dad, so he doesn’t fade from memory — that’s such a calling card for us, as the audience, as well, to reach out to those people, reach out to those relatives you may not have in a long time. I definitely reached out to my mom afterwards and then, over the holidays, after the movie came out, I took my mom and my grandmother to go see Coco. And that was really interesting, because for whatever reason, I was a wreck throughout the whole thing. And then my mom is not a big movie crier, and neither is my grandmother. So they were like, “Oh, yeah, this is cute.” And they were really enjoying it. And then, at the very end — again, that Mama Coco scene, we were all crying. It was a shared, intergenerational cry. [laughs]

[excerpt: Coco]

Ms. Tippett: Monica Castillo, interviewed by Lily Percy. This hour, you also heard Naomi Alderman, Drew Hammond, Mark Kermode, Zahida Sherman, Seth Godin, and Michael Strautmanis.

Listen to a fuller, longer, fantastic dive into each of them, as well as others like the New York Times film critic A.O. Scott — the movie that changed him was Ratatouille — that’s all on the new, second season of This Movie Changed Me. It is a podcast offering from On Being Studios, and it is a delight. Learn more, as always, at onbeing.org.

[music: “Fiesta con de la Cruz” by Michael Giacchino]

The On Being Project is located on Dakota Land. Our lovely theme music is provided and composed by Zoë Keating. And the last voice that you hear singing at the end of our show is Cameron Kinghorn.

On Being is an independent production of The On Being Project. It’s distributed to public radio stations by PRX. I created this show at American Public Media. Our funding partners include:

The Fetzer Institute, helping to build the spiritual foundation for a loving world. Find them at fetzer.org.

Kalliopeia Foundation, working to create a future where universal spiritual values form the foundation of how we care for our common home.

Humanity United, advancing human dignity at home and around the world. Find out more at humanityunited.org, part of the Omidyar Group.

The Osprey Foundation — a catalyst for empowered, healthy, and fulfilled lives

And the Lilly Endowment, an Indianapolis-based, private family foundation dedicated to its founders’ interests in religion, community development and education.

![Cover of Black Panther (Original Score) [LP]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/61zEepwLqqL.jpg)

![Cover of The Wizard of Oz (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) [Deluxe Edition]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/512ICFlxJtL.jpg)