Thomas Moore, Debra Haffner, and Anthony Ugolnik

Spirituality and Sexuality

Christian scripture and tradition have overwhelmingly shaped American attitudes toward sexuality. And in the past year, our national attention has been riveted on sexual scandal within the Catholic Church. In this program, we crack open the difficult subject of Christian tradition and healthy sexuality. What is the positive sexual ethic of the Bible, beyond the identification of sin? What does sexuality have to do with the human spirit and how might this change they way it is discussed in communities of faith?

Image by Ben White/Unsplash, Public Domain Dedication (CC0).

Guests

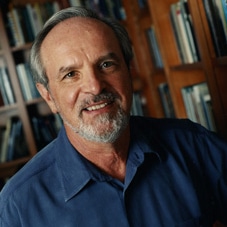

Thomas Moore is a former Catholic monk and author of The Care of the Soul and The Soul of Sex.

Debra Haffner is a renowned sexual educator, Unitarian Universalist minister, and director of the Religious Institute on Sexual Morality, Justice, and Healing.

Anthony Ugolnik Ukrainian Orthodox priest and professor of English literature at Franklin and Marshall College

Transcript

July 27, 2003

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith. Today, “Spirituality and Sexuality.”

BISHOP WILTON GREGORY: Today we have seen the passage of an important document in the history of our Conference of Bishops. From this day forward, no one known to have sexually abused a child will work in the Catholic Church in the United States. We bishops apologize to anyone harmed by one of our priests…

UNIDENTIFIED MAN: This is not only in our faith a mortal sin to do these things, but it’s also a criminal act, and if someone hides that criminal act, arguably they are obstructing justice or arguably they also are accessories to the crime.

MS. TIPPETT: Since the sexual scandal in the Catholic Church broke, more Americans than ever have been uttering the words `religion’ and `sexuality’ in the same breath. Today on Speaking of Faith, we’ll explore that connection and ask what it might have to do with healthy sexual lives, and with those of us, most of us, who live between the extremes of celibacy and sexual pathology. The sexual ethic of American society has largely been shaped by Christianity, yet there is clearly no one Christian way to think and talk about sex. And this isn’t an easy subject to crack open in a positive way. Studies repeatedly show that many Americans are alienated from their sexuality in part because of what they fear their faith tradition teaches. So in this hour, we’ll try for a new kind of conversation.

We’ll draw out three men and women who’ve wrestled with modern sexuality within a broad framework of religious values. Thomas Moore is a psychotherapist, a former Catholic monk and author of The Care of the Soul and The Soul of Sex. Father Anthony Ugolnik is an Eastern Orthodox priest with edgy views on the church’s approach to male sexuality, and Debra Haffner directs the Religious Institute on Sexual Morality, Justice and Healing. One word of caution: The language in this program is both faithful and frank. But listen carefully, if you do choose to listen, for these perspectives defy labels of right and left, prudish and permissive — the categories on which religious discussions of sex often falter. We begin with Debra Haffner.

DEBRA HAFFNER: In heaven, the Talmud says, there will be the Sabbath, sunshine and sex.

MS. TIPPETT: Debra Haffner was raised in a secular Jewish home. For over 30 years, she has been a leading American sexual educator, most recently as president of the Sexuality Information and Education Council of the United States, known in short as SIECUS. In her mid-40s, after 12 successful years at the helm of this large secular organization, she became fascinated with the link between sexuality and religion. She went to seminary, became a Unitarian Universalist minister and founded the Religious Institute on Sexual Morality, Justice and Healing.

MS. HAFFNER: I felt a calling in 1988 that I then resisted, and I was given after seven years at SIECUS a sabbatical. And I thought, you know, I’m going to go up to the Yale Divinity School and do a fellowship, and I’m going to do research on what does Scripture have to say about sex. You know, what does church tradition really have to say about sex? I was completely surprised by what I found, which was that in fact Scripture is much more sex-positive than the Christian Coalition would have led people to believe, than most people sitting in churches believe. And so as I read the Bible, I thought, wow, it really gives a message about sexuality that’s pretty close to mine.

MS. TIPPETT: What Debra Haffner found, throughout the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament, was a realistic view of human sexuality. The overwhelming message, she says, is twofold: Sex can be a pleasurable, enriching part of human relationship, and it can be abused and cause pain. She believes that the Christian church has neglected the fullness of its own tradition, not only leaving itself vulnerable to sexual scandal but impoverishing the lives of its members and communities.

MS. HAFFNER: You know, a very strange thing for me, as somebody who became involved in organized religion only in the last 15 years or so, is how did it not deal with these issues? I mean, how is it possible that you can minister to the souls of people and not talk about the most intimate part of their lives? And in all of our congregations, whether they are Unitarian or Southern Baptist or Roman Catholic or — or Muslim or Hindu, people struggled on a day-to-day basis with their most intimate relationships. People have to raise their children in a way — and deal with these issues. People have to deal with their aging parents and these issues. Many people survive sexual abuse; many people are dealing with domestic violence. You know, I could go on and on. How is it that the church hasn’t dealt with these issues? And so what we’re finding is that because of the crisis in the Catholic Church, people are now saying, `Oh, we need to do something, too.’

MS. TIPPETT: And here’s something that — that intrigues me. As I try, like you, to see the silver lining, and say, `Well, what — what can we be learning? How can we move forward in health?’ it is so clear in this negative sense that sexuality has to do with people’s souls, that people’s souls are damaged when their bodies are abused — Right? — in a very particular and excruciatingly intimate way. What’s the flip side of that? What does that say about what we might be teaching our children about how their souls and bodies are connected when it’s healthy and when their sexuality is something that is right?

MS. HAFFNER: Well, right. Right. I believe that our sexuality is one of the gifts of God or creation, depending on, you know, how one wants to think about that, that’s one of the most life-fulfilling things that God gave us, and that really — and — and you know, this is a pretty Unitarian Universalist philosophy, but that there is nothing more important than how we treat each other, that it’s — it’s affirming the dignity and worth of every person that’s the central part of our humanity. You know, I think there’s so many questions we don’t know the answer to in terms of faith. But what I do know is that the way we come closest to experiencing the divine is through our love relationships with other people. There are people who talk about sex being a path to God; people who practice Tantra talk about that. I’m not sure I…

MS. TIPPETT: Tibetan Buddhists.

MS. HAFFNER: Right, I’m not sure I think that’s — that’s true. I’m also really worried about a new performance standard, you know. You know, it’s one thing to say we have to have — you know, we’re supposed to have an orgasm each time we have sex, but we’re supposed to find God each time. You know, I just think it’s too big.

MS. TIPPETT: Raising the bar too high.

MS. HAFFNER: Yeah, right. That — but that clearly, how we treat each other and not just in our romantic relationships, but in our family relationships, our relationships with our friends, our relationships with our co-workers, our relationships with the person at the dry cleaner — you know, all of that talks about how are we living God’s intention in the world?

MS. TIPPETT: Now a light went off for me, because when you say that what is at the core of religious insight is relationship. Our understanding of God is that relationship is hallowed and we find God through relationship, then you could say that sexual relationship, which is one of the most intimate forms of human relationship, would just be a more intense expression of that. So of course, it has implications for our religious sensibility.

MS. HAFFNER: But — and as we make ourself truly vulnerable to another person, which is what happens during sexual relationships, is at that point in sharing that most base vulnerability that I think we have the opportunity to truly experience a kind of connection that is sacred if we understand it that way. You know, during the ’70s, there were a variety of Christian marriage manuals that were written, and they were written in response to the sexual revolution for traditional evangelical Christians who I think felt like they were being left out of what was going on in the culture. So there was this whole range of these sex manuals that were written, and they’re very interesting to read. One of the ones that I read talked about sitting down with your partner and praying before you had sex, and asking God to bless that time together and then praying after sex. Now I don’t know, you know, that that should be a prescription for all of us, but I was struck by what a wonderful suggestion for people in terms of hallowing their time together, that it’s not something you stick between, you know, the sports and the weather, you know, commercial on with the 11:00 news, but that you’re intentional, that you’re saying this is important time. What we’re going to share we want to bring God’s presence into that. And I think that that’s a very holy kind of way of approaching one’s sexuality.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith, with a program on “Spirituality and Sexuality.” I’m in conversation with Unitarian Universalist minister and sexual educator Debra Haffner. Several years ago, she brought together theologians from a wide range of religious traditions who were working on the subject of sexuality. And they crafted a religious declaration on sexual morality, justice and healing, which now has over 2,000 signers. One of Debra Haffner’s observations when she began to study the Bible was that the life of Jesus was much more focused on personal relationship and social justice than on condemning sinful acts, even sexual sins. The religious declaration she’s co-authored proposes a higher sexual ethic than the one we now practice, one that would place rules and apply them in the larger context of relationship. Like the New Testament Sermon on the Mount, this ethic would stress the spirit rather than the letter of religious law. Debra Haffner and the other signers of her declaration say they want to reconcile the essence of religious virtue with complex modern realities.

MS. HAFFNER: America is very confused. We profess a kind of attitude about sexuality that’s actually quite Victorian and yet people behave in ways very different than that. And so a lot of what I’m about is helping people live sexual lives consistent with their own values.

MS. TIPPETT: In something you’ve written about the declaration, you’ve said that the goal is not to develop a new sexual theology but rather `to articulate an extant theology about sexuality that is grounded in religious tradition and thought.’ But how do you respond when people say that what you’re doing is naming a lot of the sexual ethic that has evolved in the early 21st century — you know, the way it is — that sex happens outside marriage, that there is homosexuality, that there is abortion, that there is contraception — Right? — and that you’re adapting the wisdom of the ages to modern trends? What’s your response to that?

MS. HAFFNER: Well, first of all, I would say go back and read your Bible because all of this stuff is in there, and I think this is as old as, you know, us walking on two feet and probably predates that. We are human beings first and foremost, and yes, our sexuality is socially constructed. We do live at a particular time, and we understand our sexuality partially as a result of that time and place. If we lived — you know, there are cultures in the world, for example, where kissing is seen as an immoral act — you know, as the most vile thing people can do. We don’t understand kissing that way here, so we know that it’s socially constructed. But it’s also an essential part of our biology of who we are, how we are made, how we are constructed, how we were created, if we want to think theologically. Yes, part of this is about us now. I happen to believe in a God that’s revealed in the world to us today. I don’t believe that 2,000, 3,000, 4,000 years ago, that they got to understand what God was and — and it got fixed, that I think that God is revealed in history as we’re living it, as we are making it. I believe that we are co-creators with God of the life we are living. So, yes, part of it is today’s world, but it’s also, I think, based — and these theologians I think would say that it’s based on really what was intended for us in the first place.

MS. TIPPETT: As I’ve read about your work and responses to your work in the religious community that it — it’s somewhat — there is some controversy, and — and the way it’s usually defined is that you are liberal, right? And that many of the signers of the declaration on sexual morality, justice and healing represent liberal traditions. Where, for you, are the — the really important and difficult tensions? You know, what are you, as a liberal, confused about in terms of reconciling culture with — with religious tradition?

MS. HAFFNER: OK. Well, first of all, our 2,200 endorsers right now represent 35 different traditions, so that it is not just a group of people like me who are Unitarian Universalists with a — you know, some Reform rabbis and a few United Church of Christ people. I mean, truly we have 35 denominations. We have Southern Baptists, Roman Catholics, Buddhists…

MS. TIPPETT: You do have Southern Baptists.

MS. HAFFNER: …Hindus — yeah. Not a lot, but we have some.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

MS. HAFFNER: And we actually see that this statement is actually a pretty mainline kind of statement. I think the issue of how do we help people live in a — in adult, intimate, emotionally committed relationships that sustain them throughout their lives is a very tough issue. How do we raise children to understand their sexuality but also understand that sexual behaviors aren’t — are for adults, not for children? How do we, as a culture, support the idea that our sexuality is a wonderful part of life, but that you really do need this more rigorous ethic to decide whether a behavior is life-enhancing or harmful to you or someone else? So I think that those are difficult questions. The issues facing, I think, the churches across America have tended to focus in in two places. One is on the whole issue of sexual orientation, and then the issue of what to do about clergy sex abuse. We need to be talking about sexuality in a much broader sense, about who we are as men and women and how do we relate to each other in our lives. What would it be to be a sexually healthy congregation? And clearly that’s so much more than just being a place where, you know, the clergy’s not abusing anybody. And to start, it’d be a congregation where sexuality was talked about.

MS. TIPPETT: Debra Haffner is founder and director of the Religious Institute on Sexual Morality, Justice and Healing. I’m Krista Tippett, and this is Speaking of Faith, with a program on “Spirituality and Sexuality.”

THOMAS MOORE: When I studied religions, I had studied especially the — the ancient Greeks where you really had a sense that to be sexual was really OK; not only OK, but it was part of the attempt in life to have meaningful experience and to be a good person and to do the right thing. That was quite eye-opening for me, maybe because I was, you know, one of the traditional guilty Catholics.

MS. TIPPETT: That’s Thomas Moore, who in 1992 became America’s best-selling expert on the soul with his book The Care of the Soul. But a few years later, he wrote another book on one of his favorite subjects: The Soul of Sex. Thomas Moore was a celibate Catholic monk for 12 years of his early life, and he says celibacy is a life choice he continues to respect, even celibacy as an occasional temporary option for single and married people, one which can foster spiritual growth. But he’s now married with children, and he’s built a successful career as a psychotherapist. I asked him how through all these experiences, he’s come to understand the mysterious connection between the soul and sex.

DR. MOORE: Sexuality embraces many things that are very important to the soul, things like beauty — appreciation for beauty, body and sensuousness, pleasure, intimacy, even friendship. These are all issues that are most important to the soul. They’re not terribly important to the mind or to the ego that wants to get ahead in this life. They’re not nearly as important. But, you know, we don’t give a lot of attention to beauty. We can live quite a cerebral life or we can live now a life full of machines and computers and that sort of thing, but sex is especially important for the soul because it has all these values that are basic to it. So the two go together. To be sexual and to be soulful are very close to each other.

MS. TIPPETT: And, you know, that’s such a lovely thought but it’s a hard way for human beings to be in our culture in particular, and partly because of religion, right?

DR. MOORE: I know. I know.

MS. TIPPETT: So how do people — how do you want people to get there and get there with what they feel is their morality intact?

DR. MOORE: One thing I am interested in is — is how people like me were taught through religion to — to believe that sex is sacred but that it’s wrong. I mean, we’re told that it’s sacred, but, you know, there really wasn’t much behind that phrase; it was just — you know, we’re supposed to say that because it’s God-made, or it’s God-given. But in fact, it was not considered sacred. So I’m trying to restore that sense, and — and I do this in like — for example, in my book The Soul of Sex. I try to say that sex is sacred, and for one — for one thing, it is — it only really works if you can eroticize your life so that you give pleasure and beauty attention. You take care of your body. You really care for the person you’re with. Sex is not just physical. Nothing is just physical.

MS. TIPPETT: OK. So those are all qualities, those are all sacred qualities…

DR. MOORE: Yeah, right. Right.

MS. TIPPETT: …I hear that. Beauty and relationship.

DR. MOORE: Right. Right. Isn’t that enough?

MS. TIPPETT: And even — yeah. Yeah. And even a regard for the — for the body as part of creation, right?

DR. MOORE: Yes, I think so. It’s — it’s a bigger imagination — really a spiritual imagination of what life’s all about, and — and sex, then, has its place within that imagination. Instead of being outside of it, as though it’s a threat to the whole thing. And see if you think — see it as a threat, then you have to have all these moral inhibitions and rules and, you know, expectations and consequences and all of that — and threats. I mean, I grew up with all of that thing, and it’s amazing to me that I’ve come through feeling fairly OK, you know, about the whole business. Maybe my — all my attention to it is a reaction. I don’t know, but at least it’s given me a lot to think about, and I think that it’s possible without a whole lot of effort for a person to sit down and say, `Now, what’s wrong with — with the fact that I’m a sexual person? Is there anything wrong in that? Do I have to separate my spirituality from my sexuality? Can I just take both of them?’ And maybe I’m you know, maybe people have to give up some of the virtue that they feel by being so righteous about sex. If you give some of that up, then you darken your sense of you are and what it means to be a human being, and you’re more tolerant of other people and of yourself. So I think nothing but good can come of it. Our spirituality is basically too clean, too remote from human life.

MS. TIPPETT: You mean, Christian spirituality as it’s been passed on in…

DR. MOORE: Not just Christian. All kinds of spiritualities. Some Buddhist spirituality and Hindu spirituality and all kinds of spiritualities get caught in this. It’s not just Christian. It’s in the nature of spirit to — to be so interested and caught up in it, you go too far and you go from sort of a moderate appreciation of something other than just physical life to suddenly thinking that the body is a source of evil, and I think it’s the extreme that we have problems with.

MS. TIPPETT: Where do you find in — I don’t know. I’m curious about texts or music or even Scripture that are important to you now as a religious person — where do you find inspiration for this way you’ve thought about sex theologically or spiritually?

DR. MOORE: Well, the obvious thing to say would be the biblical Song of Songs, which is so beautiful. It’s so beautiful and so sensuous, and I know that people have sometimes tried to explain it away as saying it’s not really supposed to be sensual or it’s all pure metaphor. But that’s really stretching it. You can take that I think I say somewhere in that one of those books that if I had a church, if I were a priest now, I’d want to probably have the Song of Songs done in lettering on the wall somewhere so that people could — could read it and help them reconcile their sensuality and their spirituality.

READER: The song of songs, which is Solomon’s. Kiss me. Make me drunk with your kisses. Your sweet loving is better than wine. You are fragrant. You are myrrh and aloes. All the young women want you. Take me by the hand. Let us run together. My lover, my king has brought me into his chambers. We will laugh, you and I, and count each kiss better than wine.

MS. TIPPETT: This is Speaking of Faith, and you’re listening to a conversation with former Catholic monk Thomas Moore, author of The Care of the Soul and The Soul of Sex.In that book, Thomas Moore describes how his current work as a psychotherapist has furthered his religious sense of a relationship between the soul and human sexuality.

DR. MOORE: Well, there’s one thing that I noticed as a therapist is that a great many people I mean, over half the people who came to me for therapy came with a sexual issue of some kind — sexual problem. And I thought — you know, when it was presented to me, I never felt that my job was to solve this problem or even to help the person solve the problem for themselves. My problem was to see that there’s some mysterious thing taking place in this person’s life. I knew from my studies in religion that when people go through rites of passage, like when they go from childhood to adulthood or marriage or illness, that the rituals often were sexual in nature. There was a sexual side to the rituals. And I just reversed that. And it seemed to me that when people, then, came to me with sexual problems, I tried to see that then as a rite of passage, that there was something going on where suddenly their sexuality was fired up, and it was creating a problem because it doesn’t take much fire to threaten a marriage or a standing partnership. And I would see it, then, as not something to change, that this was a terrible problem to solve, but it meant that there’s something we had to address. Life wanted to move on. There was something that wanted to move ahead. And I would hear a lot of the sexual language more broadly than just having to do with these two people trying to work out their sex life; as having something to do more with dealing with — with the whole of life rather than just that part.

MS. TIPPETT: And what you’re saying — I understand it and I appreciate it, and at the same time, I know that speaking like this can sound quite threatening, even, you know, to the moral fabric of our society, and frightening because I mean, one thing that those of us who are raising children have tomorrow about is, you know, that it seems very hard for people in our time to sustain meaningful relationships over time. And — right? And so somebody might say, well, what you’re describing is so you get sexually fired up and is can that really be a reason to leave a marriage or — or to diminish important relationships? So what’s you know, what’s around that for you?

DR. MOORE: Well, one thing is that I don’t think that my approach is a threat to the marriage at all. In fact, I’m trying to say that like let’s say a person comes to me and they say, you know, they’re married to somebody and they’re attracted to someone else and it’s really bothering them. I’m trying to say that there’s something else going on. You don’t just need to switch partners. That’s taking it purely — purely as a literal sexual issue. I mean, I have a great faith and love of marriage. On the other hand, there are differences among people, and also differences in different stages in a person’s life, and there may be a time in life when getting married and settled down is just the wrong thing. And a lot of people make mistakes. They do it at the wrong time and they discover it too late. And that’s an issue that has to be worked through. I but I’m not at all recommending acting out these things at all. Just that when I say that your sexuality is fired up, I would not support acting that out, but rather to really explore it and see a lot of the ramifications, taking it very seriously, but in a broader sense than just sex. So in the long run, I think what I’m suggesting is a deeper motivation for a much more ordered sexual life.

MS. TIPPETT: Thomas Moore’s most recent book is The Soul’s Religion: Cultivating a Profoundly Spiritual Way of Life. This is Speaking of Faith. Today we’re pursuing a frank conversation about the connection between sexuality and religious tradition. After a short break, we’ll return with Eastern Orthodox priest Anthony Ugolnik, who is writing a provocative book entitled Living in Skin. I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us.

Welcome back to Speaking of Faith. Today, drawing out thought-provoking perspectives on sexuality and spirituality.

[Excerpt from a Ukrainian folk song]

This is a Ukrainian folk song for the Feast of St. Peter. In some Ukrainian villages, this day of religious observance is traditionally marked by marriage proposals and wedding celebrations.

Eastern Orthodox Christianity, the dominant religion from Greece to Russia, is in many ways more comfortable with the blending of body and spirit than Western traditions.

ANTHONY UGOLNIK: You know, if you’re raised in kind of an East European culture with kind of an openness and frankness about the body in its humor and in its song, in its dance, you know, there’s a joy in one’s being, in one’s embodiment that is lacking us, I think, in the States and in America. I am grateful for that.

MS. TIPPETT: Anthony Ugolnik is a Ukrainian Orthodox priest. Eastern Orthodoxy is as ancient as Roman Catholicism, but Orthodox priests are allowed to marry, as Anthony Ugolnik has. Though in many respects, he’s a very traditional Christian, his thinking on sexuality is not. But it defies the split between liberal and conservative that is tearing many American Christian denominations apart. He’s at work these days on a controversial manuscript about male sexuality, which I heard about on the theological grapevine. He’s sensitive to criticism, including feminist perspectives, that traditional religion has been dominated by men. And yet he also notes that most of the sacred imagery of the church takes feminine form, the ubiquitous figure of Mary being just one example. Meanwhile, he says, the male body has been exiled from Christian spirituality, and Father Ugolnik believes that this has done violence to men and to women and to the church itself. His sense of the problem begins with American culture.

FR. UGOLNIK: You know, one model that a paradigm that I see all the time living here in Pennsylvania Dutch country is, you know, riding in my car behind horses and buggies with Amish teen-agers in them during courting season or Amish couples. And there are these people dressed in a very 19th century way to us, and you know, their bodies covered. And in the middle of this sort of idealized image the tourists flock here to see, there are huge billboards looming: women in bikinis and, you know, guys in shorts in Calvin Klein ads. And you know, you’ve got people sort of exhibiting the skin and parading the body and selling things. And I think the eroticism of any of us — Amish guys included — is affected by the commercialization of sex all around us. You know, so we are socialized to sex and to our own sexuality in lots of ways, and they’re conflicting, clashing ways. And as a person in the church and who’s devoted to the church, I want to see the church dealing with sexuality in its own way. But it doesn’t. It doesn’t. It avoids that topic and it likes priests who avoid it. And that’s a problem for me.

MS. TIPPETT: I have a sense, though, that in Orthodox tradition, in your tradition, there is a more earthy sexuality, let’s say, than in Protestant Christianity.

FR. UGOLNIK: Oh, there is. There is. It’s a rich and sensual tradition, and we contain within ourselves all kinds of resources to deal with this problem. Unfortunately, we don’t exploit them very effectively. We live out this embodied liturgy and we engage all of the senses in our worship and our poetry — even our poetry in the context of worship in our hymns are really sensual and profoundly sexy. But I think in discourse with other Christians, we can be rather shy of that and ashamed of it.

MS. TIPPETT: So tell me what finally got to you that you needed to sit down and think and write on this subject.

FR. UGOLNIK: And write and write. Yeah. I was involved athletically with the hockey team for a number of years, about 10 to 15 years. And it suddenly struck me that these young guys that I was training on the ice were very much ill at ease with their own masculinity. We had tons and tons of courses and groups and centers devoted to women, women’s issues, women’s bodies, women in anthropology, women in literature, and virtually no attention paid to masculinity as it develops in these young guys. Now of course, the reason is that we’re carrying around academically the legacy of 2,000 years of kind of male prerogative and privilege, but the fact is that these young guys we’re teaching are brand-new to those bodies. They’ve only been living in those bodies for two or three years at most, and they are suffused with a boisterousness of body, they’re suffused with hormones, they’re — they want nothing else — nothing more than to be men attractive to the opposite sex, and they get conflicting signals all the time with respect to what constitutes that attractiveness.

MS. TIPPETT: And how did the person of faith, the theologian in you wrestle with that? And what was…

FR. UGOLNIK: Wow.

MS. TIPPETT: …your reaction to it?

FR. UGOLNIK: You know, I think any man of faith wrestles with issues relating to his sexuality all the time. And as I lamented before, the church often doesn’t give us the resources to do so effectively. We can sacramentalize so much. We can sacra — sacramentalize our parenthood, our fatherhood, we can sacramentalize motherhood and — and feelings of compassion. But our sexuality is isolated often from contemporary Christianity. And it’s really tough to do that.

MS. TIPPETT: Any…

FR. UGOLNIK: I think that biblically, you know…

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

FR. UGOLNIK: …it’s done really effectively, and I think it’s done by sort of disciplining the natural desire for power and mastery that’s implicit in male eroticism.

MS. TIPPETT: You note something in your writing that — that we’ve completely lost the maleness of Jesus in the way we…

FR. UGOLNIK:

Yes. MS. TIPPETT: …even — even in icons, even in pictures…

FR. UGOLNIK: Right.

MS. TIPPETT: …that Jesus is so feminine and so gentle and…

FR. UGOLNIK: He’s — he’s too sweetsy, cutesy, gentle, fuzzy-wuzzy, you know. And he doesn’t have anything of the power and majesty that he should. But, you know, women have a problem with that — the maleness of Jesus and I don’t blame them. It has to be seen in the context of his call to service, and he is empowered that he might surrender that power in service to those whom he loves.

MS. TIPPETT: Did you know all that before or was this something that you started to discover as you delved into these texts? I mean, was this a…

FR. UGOLNIK: Oh, it was — it was a discovery. It was a discovery. I think I knew it. I mean…

MS. TIPPETT: You knew it, but you didn’t know it was in the Bible…

FR. UGOLNIK: …in a s — I knew in a sense that I was in love with somebody, and y — I’m not a celibate priest. I’m a married and, you know — I’m deeply in love with a woman to whom I am sacramentally linked. And sex always seemed to me to be a sacrament. It’s a sacramental thing.

MS. TIPPETT: Talk about your definition of the word `sacrament.’ What are the words you want to put around that? Yeah.

FR. UGOLNIK: Oh. Well, I think…

MS. TIPPETT: I think that’s a word you use so much you probably have trouble giving a definition.

FR. UGOLNIK: It is. It is a word I use a lot — we use a lot. But our very being can be sacramental in th — anytime that an outward, sensusally experienced phenomenon can convey grace and be a manifestation of the presence of God, it’s sacramental in its nature.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and you’re listening to a conversation with Anthony Ugolnik, a Ukrainian Orthodox priest and professor of English literature at Franklin & Marshall College in Pennsylvania. As a teacher, he often uses the poetry of John Donne, the collection of the so-called holy sonnets that Donne wrote in the first years of the 17th century, expresses love for God through strong physical imagery. And Anthony Ugolnik finds that Donne’s 400-year-old words touch his students, particularly young men.

READER: Batter my heart, three-person God, for you as yet but knock, breathe, shine, seek to mend, that I may rise and stand or throw me, and bend your force to break, blow, burn and make me new. I, like a usurped town to another due, labor to admit to you, but oh, to no end. Reason, your viceroy in me, me should defend but is captive and proves weak or untrue. Yet dearly I love you and would be loved fain but am betrothed unto your enemy. Divorce me, untie or break that knot again. Take me to you. Imprison me, for I, except you enthrall me, never shall be free nor ever chaste except you ravish me.

MS. TIPPETT: “Batter My Heart” by John Donne. This is Speaking of Faith. Anthony Ugolnik makes a bold suggestion. For the spiritual health of laity and clergy alike, religion must embrace the uncomfortable reality of human sexuality rather than seeking only to tame it. And in Catholic tradition in particular, he regrets the virtually absent voice of the sexually active male because there is a celibate priesthood. Given this belief, I asked him how has he responded personally to the scandal in the Catholic Church, which is full of disturbing images of male sexuality?

FR. UGOLNIK: With anguish. With anguish because I know so many Catholic priests who have chosen to be priests and have taken celibacy along with that choice. And I know monastics who embrace both celibacy and their way of life as their own vocation, and I think it is — it can be a manifestation, a means of living out this life of grace, but I — I’ve seen it sort of demeaned and — and I’ve seen it besmirched and I think that one of the problems is that sex as transgression is a “normal,” in quotes, way of looking at sexuality, as Christians are supposed to see it anyhow. I mean, people who even live within the Christian tradition often think of sex transgressively. I mean, they feel kind of ashamed whenever they think about it, even if they are “allowed,” in quotes, to have it or not.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

FR. UGOLNIK: And that’s really a sad thing.

MS. TIPPETT: So that — you mean that’s sort of a backwards support for — for celibacy, not the right way to…

FR. UGOLNIK: It is. It’s not the right way at all.

MS. TIPPETT: …to affirm it.

FR. UGOLNIK: Yeah. Not the right way at all. Of course, not being Catholic, I don’t understand the Catholic imposition of celibacy. I think celibacy can be a calling. I think it can be a means of living out a life of dedication to God and to the spirit, but when you make it in essence a condition for receiving a call to ministry, as a priest myself, it doesn’t make any sense to me.

MS. TIPPETT: And for you, being a priest is wholly compatible with being a sexually active person.

FR. UGOLNIK: I think for me, it’s more compatible with being a sexually active person. In other words, my priesthood is intimately connected with my living out my sexuality in marriage.

MS. TIPPETT: Can you say some more? Why?

FR. UGOLNIK: Our — our — our communities — I’m in a small Ukrainian Orthodox church now in, you know, a small kind of Rust Belt town, and I love the place very much. And those people want a married priest, and I think that a married priest understands the lives in which they — you know, they — they deploy themselves as Christians in this society, in this culture m — better.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

FR. UGOLNIK: But I’ve also felt as a priest, because we look like Catholic priests when we walk around — I’ve felt the kind of cold shoulder, the glance that priests receive now since the scandal has hit affect us all. And I — I — my heart aches for Catholic priests and what they must be going through now. It just aches for them.

MS. TIPPETT: OK. But as — aside from that, the fact that we’ve all been bandying about the words `sex’ and `religion’ in the same sentence and it’s been on the headlines of newspapers and it feels — you know, the relationship that — that is portrayed is a twisted one.

FR. UGOLNIK: It is. They treat it — or it is treated as if they are polarities, and that’s precisely the problem.

MS. TIPPETT: OK.

FR. UGOLNIK: You know, like sex and religion are incompatible, and — and sex and abuse or religion and abuse — I mean, abuse coupled to the word `sex’ renders that sex transgressive. It renders it sinful. But sex and religion are just fine. Sex and spirituality.

MS. TIPPETT: Sex and spirituality. But I’m wondering…

FR. UGOLNIK: Sex and sacramental…

MS. TIPPETT: …is that message, though, anywhere to be heard or do — is there a way in which we — we might in our response to this crisis start talking about that more openly?

FR. UGOLNIK: Yes. I think that you can, first of all, look at the more sensual and sexually elusive dimensions of liturgy itself — that is, worship.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

FR. UGOLNIK: That is, in my tradition. And in the Catholic tradition, too. There are all kinds of rich possibilities for that. Christ — the imagery in Holy Week is that of the bridegroom, and you know, it’s not there without any reference to sexuality whatsoever. Come on. You know, I mean Christ as bridegroom and the s — church as, in some sense, bride or the — the waiting soul as bride, those are very ri — those — those offer all kinds of rich possibilities for the sanctification of sex and sexuality. And I think we’ve got to give the message to our people and to our kids in particular that what we are preparing them for is not to avoid sex. I’m so — I mean, my kids — good Lord, whenever I’d send them to a retreat, they would say to me, `Please, no more talks about premarital sex,’ you know, just don’t torment with us — with that anymore. We have to teach them that what we’re preparing them for is good sex. I mean, good sex in the best sense of the word, not just good because it’s virtuous but good because it’s full and rich and, you know, the — the most profoundly touching, you know, to the centers of our being and the being of the beloved. This is not the phony superficial stuff they see in the billboards.

MS. TIPPETT: Hmm.

FR. UGOLNIK: That’s the way we’ve got to teach it. That’s how we’ve got to approach it.

MS. TIPPETT: You wrote to me before this conversation, when I asked you about the manuscript.

FR. UGOLNIK: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: You said, `To be honest, I was sorry I had wrestled with the issue.’

FR. UGOLNIK: Yes.

MS. TIPPETT: `It seemed like a minefield. I could please neither the right, who found my frankness shocking, nor the left, who didn’t like my suspicions that some feminists didn’t quite understand the masculine experience.’ So I wonder if these very categories, though, that Christians have fallen into of right and left, of conservative and liberal, aren’t part of the problem. I mean, do we need to…

FR. UGOLNIK: Oh, I’m so glad you said that.

MS. TIPPETT: …construct — Huh? Do we need to construct new ways to talk about what the poles are and what the tensions are?

FR. UGOLNIK: Well, sure. You’ve got to talk to some people in the middle, I guess, like you’re doing right now. The people I hear quoted most — I’m a public radio addict. But the people I hear quoted, both in this context and in the mainstream media, lie at those two polarities. I mean, they want a position from the right, they go to Falwell; from the left, they go to probably Bishop Spong…

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

FR. UGOLNIK: …you know, in the Episcopal Church, and you’ve got Falwell-Spong, Spong-Falwell, and the masses of people lie, as I do, you know, somewhere, in some combination living at the borders, you know, like most of us do, and trying to live out our faith.

MS. TIPPETT: Anthony Ugolnik is author of The Illuminating Icon.

[Excerpt from “Ikon of Eros]

Icons, sacred images and pictures, are revered in the Eastern Orthodox Church. Usually these take the form of religious pictures painted on murals within the church or on wooden panels used in private devotion.

Sir John Tavener is England’s most acclaimed contemporary composer. He converted to Russian Orthodoxy in 1977 and later joined the Greek Orthodox Church. And he recently premiered here in the States a huge musical icon for violin, chorus and orchestra, which he titled “Ikon of Eros.”

[Excerpt from “Ikon of Eros”]

The choir sings very softly with the orchestra. The text throughout the piece is simple and consists of a few words: `Eros,’ the Greek word for sexual love, `ecstasy’ and `metamorphosis,’ or transformation.

[Excerpt from “Ikon of Eros”]

When I began to consider this program, I wanted to open up the mysterious yet strong connection between spiritual life and sexuality. In American public life, we focused recently on the dark side of this connection. But can the Christian religion be as powerful a positive force in human sexuality? Anthony Ugolnik, Thomas Moore and Debra Haffner suggest that it can. So too does this religious music of Sir John Tavener. It conveys light, passion, beauty and vulnerability — common qualities of the soul and of human sexuality at its best.

[Excerpt from “Ikon of Eros”]

The voices in this hour insist that sexual scandal should encourage communities of faith to bolder realism and honesty of discussion about sex,and that they can take their cue in this from the Bible itself. I wonder how a greater emphasis on the overriding biblical ethic of relationship, as Debra Haffner proposes, would reframe sexual teaching and debate. Finally, I’m left with Anthony Ugolnik’s idea that Christian tradition contains untapped resources for actively nurturing sexual lives which are good in every sense, joyful and moral, an expression of the sacred.

We’d love to hear your comments on this program. Please send us an e-mail at [email protected]. That’s M as in Minnesota, mpr.org. Or you can call Minnesota Public Radio at 1 (800) 228-7123. We’d like to hear from you. You can also contact us through our Web site at speakingoffaith.org. There you’ll find links, a list of books for further reading and music that we’ve used in this program. And when you visit our Web site, you can also listen to this program again, as well as our previous programs. Again, that’s speakingoffaith.org.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.