Vincent Cornell

The Face of the Prophet: Cartoons and Chasm

Our guest, an American Muslim and religious scholar, helps untangle the knot of violent and bewildered reactions to cartoons depicting the Prophet Muhammad.

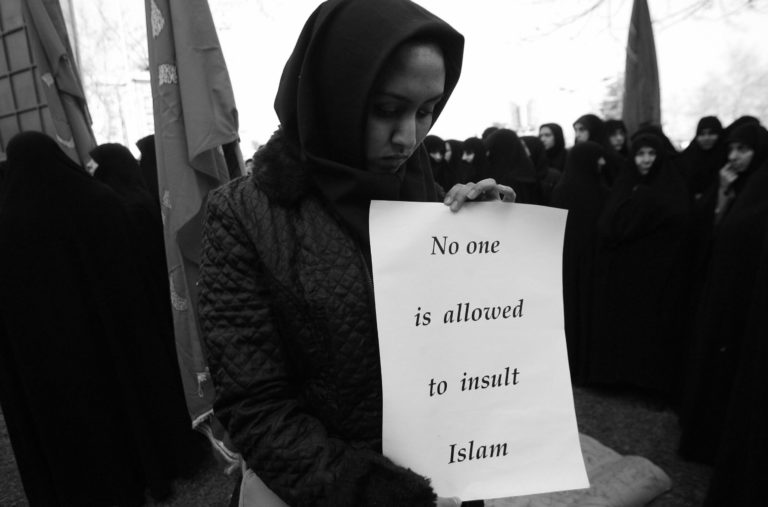

Image by Behrouz Mehri/Getty Images, © All Rights Reserved.

Guest

Vincent Cornell is Professor of History and Director of the King Fahd Center for Middle East and Islamic Studies at the University of Arkansas.

Transcript

KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: I’m Krista Tippett. Today, “The Face of the Prophet: Cartoons and Chasm.” My guest, Vincent Cornell, sees both sides of the crisis over caricatures of the Prophet Muhammad. He describes in detail why some of these images were deeply offensive to an intellectual and moderate Muslim like him. Cornell is an American Muslim respected in circles of global Islamic scholarship. He insists that violence in the name of Islam is always a betrayal of the core of that faith, that Islam is in the throes of a reformation, and together, he says, we must trace the line between freedom and moral responsibility.

MR. VINCENT CORNELL: You know, freedom of speech does not mean complete license to insult and inflame. There’s a certain place where freedom of speech comes close to the analogy of calling “fire” in a crowded theater.

MS. TIPPETT: This is Speaking of Faith. Stay with us.

I’m Krista Tippett. There is a difference between exercising freedom of speech, says my guest today, and shouting “fire” in a crowded room. This hour, we’ll try to untangle the knot of violent and bewildered reactions to cartoons depicting the Prophet Muhammad. Vincent Cornell says events of recent weeks have incited deep-seated outrage among Muslims that the West must take seriously.

From American Public Media, this is Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics and ideas. Today, “The Face of the Prophet: Cartoons and Chasm.”

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: Satirical cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad were first published in the Danish press last fall. Danish Muslims responded immediately with petitions and other peaceful forms of protest. They created an umbrella group, the European Committee for Honoring the Prophet, and tried in vain to press the Danish government to respond. When that failed, they took their appeals to global Islamic groups. In the months that followed, the offending images were circulated around the globe. They were reprinted by several European newspapers as an exercise of freedom of the press. In recent weeks, thousands of Muslims have rallied, sometimes violently, from England to Pakistan to Indonesia.

REPORTER 1: Well, it started last fall when the editor of a local newspaper here in Copenhagen invited the Danish Cartoonists Society to draw cartoons of how they see Muhammad. Then after the following week, some local clerics used their Friday prayer sessions to attack the cartoons and…

REPORTER 2: There are few countries in the Middle East where there have not been protests. In Iraq, thousands of Sunni and Shiite Muslims have been burning Danish…

REPORTER 3: The crowd reportedly firing shots at the base, throwing grenades at the building. Five Norwegian soldiers were injured in these clashes.

REPORTER 4: Now, in this country, newspaper executives are trying to figure out the best way to cover the story. Few U.S. publications have reproduced the offending cartoons.

REPORTER 5: This is a clash between press freedom and religious respect, which is proving difficult to resolve.

MS. TIPPETT: In order to understand this spiral of events, we turn this hour to an American Muslim with deep connections in global Islamic circles. Vincent Cornell is professor of history and director of the King Fahd Center for Middle East and Islamic Studies at the University of Arkansas. He converted to Islam in the late 1960s after studying comparative religion at Cornell. He spent extensive time teaching in Muslim countries, including Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt, Malaysia and Indonesia. In recent years, and again in recent weeks, Vincent Cornell has watched world events with a sense of religious and personal grief. He considers any violence in the name of Islam a betrayal of the spiritual and theological core of that faith. But he has also shared the outrage many Muslims felt at apparent European prejudices represented by cartoon depictions of the Prophet Muhammad.

MR. CORNELL: Well, I think it’s important to get a sense that these cartoons are not simply innocuous jokes or cartoons that are poking fun at people for their normal foibles. They’re not the sort of thing you might hear on Jay Leno. That a number of these cartoons are, I believe, extremely inflammatory in at least what they imply about Islam, and also because of the fact that they’re using the Prophet Muhammad, often as a foil for everything that they want to impute to Islam as, I guess, the opposite of liberal Western society.

One cartoon in particular is interesting. It’s the face of the Prophet Muhammad in a turban. The face is framed by a star and crescent. The crescent frames the face, gives the appearance sort of as a sword or a sickle and the star is stuck in the Prophet’s right eye. Another cartoon has the Prophet Muhammad holding a dagger or a scimitar, a short scimitar in his hand, with a bushy beard looking sort of like typical 19th-century images of the Mad Mullah. Behind him are two veiled women, veiled completely in black. The only thing visible about the women is their eyes. The eyes are made to sort of stand out, big, wide-staring eyes, sort of like a deer caught in the headlight. And the Prophet’s eyes are obscured by a bar as if the Prophet is a criminal. Again, this is, you know, not simply a statement that Muslim men have a problem in terms of seeing what they do to Muslim women. It’s an entire image of violence having to do with the sword that adds to the particular picture.

MS. TIPPETT: I did see that one and it evokes an incredible sense of violence to those women.

MR. CORNELL: Of course, the most famous or infamous one is the picture of the Prophet with the turban on his head that’s a bomb. But more than just having a turban on the head that is a bomb, underneath the fuse of the bomb is a sort of a badge, a symbol, where it says, la ilaha illa Allah; Muhammadun rasul Allah, “There is no God but God; Muhammad is the messenger of God.” So more than conveying the image that there is something violent in Muslim sensibilities or in Muslim expression, there’s the very strong image in this cartoon that the problem is not just the Prophet Muhammad, the problem is Islam itself, that there’s something inherently violent in Islam.

And the cartoon that again, it’s probably better to call them caricatures than cartoons, the caricature that struck me as most interesting that hasn’t been discussed anywhere, as far as I know, is a caricature where there are very, very simple, almost stick figures that are indicating that they’re probably Muslim women. I mean there are circles and lines that sort of look like a headdress or the veil that Muslim women wear. The mouths, as these women speak, are crescent moons. But I thought what was most interesting is their eyes are Stars of David. And this, I think, to me at least, gives me the sense that what we’re dealing with here is something broader than simply an anti-Islamic polemic. There may also be overtones of an anti-Semitic polemic in the sense of sort of the well-worn images of European anti-Semitism.

And so again, there are other cartoons or caricatures that are a little softer in the sense that there’s a picture of a Danish cartoonist drawing a picture of the Prophet and he’s scared because he’s being told that the journalists of this particular paper are a bunch of reactionary provocateurs. But I have to say that whether they’re reactionary or not, I think they certainly are provocateurs.

And the provocative, inflammatory nature of these caricatures I think are important for people to realize. I think anyone who has a sense of self-worth, especially in a minority community, in the sense of self-respect and is trying to assert themselves as an accepted member of society, is going to be shocked by images such as these. And indeed, my understanding is that’s what happened within the Danish Muslim community back in September when these caricatures first appeared, that there were demonstrations. Now, they were peaceful demonstrations but the Danish Muslim community at the time expressed its outrage in exactly the way that one would expect within the democratic society. This was a nonviolent expression and by all accounts, was done peacefully. What happened since, of course, is a very, very different order of things.

MS. TIPPETT: I looked at these images on the Internet. I couldn’t see everything that you’ve just described. People can’t automatically or easily necessarily see what is offensive to Muslims. The other point, I think, the other bafflement has been, as you say, there were peaceful protests in Denmark months ago when these were first published. But what we’ve seen more recently are violent protests, and I think a sense here that you couldn’t — I do think that many Americans are walking around saying, “You couldn’t draw a cartoon of anything. You couldn’t draw a caricature of Jesus, even, that would elicit that kind of violence that would result in, you know, embassies being burned.”

MR. CORNELL: There are two issues involved here. There’s the issue of why something like this would make Muslims angry in the first place, and then, of course, there’s the second issue of the level of the Muslim response. To be perfectly clear, the Muslim response is, I think, excessive, and unfortunately, it serves as another example of how Muslims tend to fall into the trap of confirming the worst aspects of the…

MS. TIPPETT: Right, these stereotypes, yes, yes.

MR. CORNELL: …stereotypes that are often made of them. This is, I think, you know, from not just the point of view of freedom of speech and civil society and civic discourse, just from the point of view of sort of practical politics. It’s a very, I have to say, openly stupid thing to do. I mean, this is — it’s not giving an image of the Muslim world and Muslim sensibilities that’s going to make Muslims sympathetic in the eyes of people who don’t understand Islam.

But let me say a few words about why the Prophet is such a sensitive subject. And I think it’s important, when you look back at Islamic history, to see that, typically, Muslims have been more worked up about perceived and real — trying to find the right word here — insults to the Prophet or denigration of the Prophet, than to anything else. Even in the Middle Ages, it was, you know, it was very possible for Christians and Muslims or Jews and Muslims or Jews and Muslims and Christians to have lively debates about theology and about the nature of God, and no one was going to get very worked up about it. But if someone said something defamatory or derogatory about the Prophet of Islam, this was a very, very different matter.

In Islam, the Prophet is not simply just a human being. The Prophet is called “the Beloved of God,” habiballah. He’s considered the best creation of God. Even those Muslims do not believe that the Qur’an came from the Prophet in the sense that the Prophet composed it…

MS. TIPPETT: Didn’t write it, yeah.

MR. CORNELL: He didn’t write it.

MS. TIPPETT: He recited it, uh-huh.

MR. CORNELL: The Qur’an came from the Prophet’s mouth through the mediation of the angel Gabriel. And so one can’t really talk about the Qur’an without talking about the Prophet. In addition, the Qur’an itself says that the Prophet Muhammad is the main interpreter of the Qur’an. So what Muslims understand of the verses of the Qur’an is first guided by the statements made by the Prophet that have been recorded in the traditions called the hadith that have been passed on through Islamic history. But beyond that, there’s sort of a cult of love for the Prophet Muhammad that over the centuries has gone beyond the sort of exegetical model that I’ve been talking about over here in the sense that the Prophet is a paradigm for humanity in general, he’s an exemplar for human behavior, he’s an exemplar for virtue, he’s considered a model, not just for men but for women as well, for all human beings. And even in the Sufi tradition, as time developed in Islamic history…

MS. TIPPETT: The mystical and spiritual tradition of Islam, uh-huh.

MR. CORNELL: Exactly. There was a movement that was called al-tariqa al-Muhammadiyya, which literally means “the Muhammadan way,” in which the Sufis sought to assimilate themselves to the prophetic personality as a way of getting close to God. So the Prophet Muhammad is a man but he’s a man unlike other men. He’s not divine in the sense that Jesus is divine in Christianity, but perhaps the Sufis put it best. They said, “the Prophet is a man like other men in the way that a ruby is a stone like other stones.”

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, “The Face of the Prophet: Cartoons and Chasm.”

We’re turning to Vincent Cornell this hour to understand the sources and implications of Muslim reactions to depictions of the Prophet Muhammad in the European press. While calling for religious tolerance, opinion leaders in the United States and Europe have widely defended such publication as an expression of freedom of speech.

MS. TIPPETT: What I’ve been hoping for or grasping for is an analogy, and maybe there isn’t one. The analogy is not what would happen if you drew a cartoon of Jesus or of the Bible or even of God. I mean, that happens all the time in Western publications. Still, you have to stretch to think of images, any images in this culture or in Western European culture, that would evoke the same response. Are there images that come to you or analogies we’re not seeing?

MR. CORNELL: Well, the analogy that I’ve been using with my students in class has been the furor that was kicked up some years ago over an exhibition of art in England where there was an image of Christ that was called “Piss Christ,” where there was Christ on the crucifix, if I remember the image correctly, immersed, at least partly, in a bottle of urine. For Muslim sensibilities, the kinds of cartoons or caricatures that I’ve been talking about and describing to you, are very analogous to this. I mean, it’s an insult to them as people, to them as human beings, to Muslims as members of the world community and world society, but also it’s an insult and a denigration of that which they hold most dear within the religion, something that most — I think most touches the emotional chord.

If you want to go back, say, and use 17th- and 18th-century Enlightenment terms in your thinking about the concern of religious enthusiasm, which was the word that was used them for fanaticism, say, by John Locke and people like that, it is these kinds of images that excite the religious enthusiasm of Muslims in ways that other images can’t. Now, by the way, many people have talked about how images of the Prophet are banned in Islam. That’s not entirely true.

MS. TIPPETT: I’ve understood that, right. Tell me about that.

MR. CORNELL: The Shia tradition, for example, of Islam, has pictures of Ali, pictures of the first 12 imams, who were descendants of the Prophet, pictures of the Prophet himself. In most cases, at least in the early tradition, he was veiled. But in some cases, he’s not veiled. And so there are some traditions within Islam that allow such depiction. There’s nothing in the Qur’an, for example, that says one cannot depict the Prophet or depict major figures of Islamic history. There are some traditions in the hadith collections, these are the traditions of the Prophet, that indicate at least a negative attitude toward anthropomorphic depictions. But, again, this is more a matter of cultural acceptance, cultural belief. What started as a ban on anthropomorphic images in places of worship eventually spread into the society and included a ban on anthropomorphic images especially having to do with religious figures in Muslim society and art in general.

But again, I think — I’m also going to separate these particular cartoons from the initial cartoons of a cartoon book on the Prophet’s life that may have been of a very different order. When it comes to things that are created to insult and incite, at the very least, one has to point out that in a civil society, a civil society is both civic and civil in the sense that, you know, there are certain responsibilities in which minorities or people of different beliefs allow people of other beliefs to express themselves freely and not to be put under the gun for expressing their beliefs. But by the same token, civil society is supposed to be civil. It’s supposed to be founded on mutual respect. What you have here is something that is very, very far from mutual respect. And I think it’s important to note that a lot of the discourse that we’ve been hearing over the past couple of weeks has involved a heavy dose of hypocrisy on both sides of the equation.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, talk to me about that. Talk to me about the hypocrisy on the Western side of the equation.

MR. CORNELL: Well, you know, for example, you know, I mentioned the problem about the “Piss Christ” and the great furor that arose over that when that particular exhibit…

MS. TIPPETT: But I don’t think — I mean, embassies weren’t bombed, you know.

MR. CORNELL: No, embassies were not bombed.

MS. TIPPETT: Buildings weren’t set on fire and people didn’t die because the violence was so extreme.

MR. CORNELL: Well, that’s true. However, Nikos Kazantzakis, when he wrote The Last Temptation of Christ, was excommunicated from the Greek Orthodox Church. And you know, if one believes in the salvation model of Greek Orthodoxy, that means he’s destined completely for hell. So that — you know, have to think about that as a rather extreme reaction. But again, I’m not trying, in any way, to justify the actions of Muslim mobs or even to apologize for them. I’m trying to put things in a context in which, I think, the listener hopefully can realize that there are people on one side of the equation who are trying to incite, there are people on the other side of the equation who are very easy to incite, and along with that, you have leaders of Muslim Islamic political parties in the Muslim world who find this kind of controversy grist for their mill.

Many Islamists or Islamic parties, especially those on the right of the spectrum, depend for the adherence of their members on the notion that the West is out to get Islam. If people didn’t think the West was out to get Islam, they wouldn’t join these parties in the numbers that they do. Controversies like this, incitement like this, leads people to think that these claims are true, that the West is indeed out to get Islam.

MS. TIPPETT: So the irony that these cartoons, which would be a form of Western critique of kind of politicized Islam, in fact, play into those movements?

MR. CORNELL: Certainly, but I’m not even sure if you can call this a critique. You know, for example, if the cartoonists in Denmark were using figures other than the Prophet Muhammad, you know, talking about extremism within the Muslim community, problems within the…

MS. TIPPETT: If it was a picture of Osama bin Laden rather than…

MR. CORNELL: A picture of Osama bin Laden or even a picture of sort of an ordinary Danish Muslim imam or something, it wouldn’t, I think, arouse the same kind of passion as this. Muslims might take umbrage to it, they might think it’s unfair, but this, I think, would be understood to fall within the category of civic discourse and civic debate within civil society. Talking about the Prophet or depicting the Prophet in this way, I think, moves it to a very, very different level.

It’s important for people to remember that when, say, The Last Temptation of Christ came out, Muslims objected to the film as well as many Christians because Jesus is a revered figure in Islam and Muslims themselves felt that this was not an acceptable way of depicting the life of Christ. Some Muslims even stood up and took the side of Jews who were objecting to Mel Gibson’s film of The Passion recently. So again, there are Muslim leaders, many Muslim leaders, who are, in a sense, let’s say playing by the rules, who are doing what you would expect them to do, sort of standing up in common cause with religious leaders from other traditions whenever they can. However, of course, there are others who are more extreme and who do manipulate public opinion. And I think, to a large extent, many of these demonstrations, especially the more violent manifestations, are being supported and pushed by people who have ulterior — political ulterior motives.

MS. TIPPETT: You said a moment ago people who are inciting and people who are easy to incite. What is it that leaves Muslims vulnerable to this kind of anger and this deep sense of offense right now?

MR. CORNELL: Well, it differs somewhat from country to country but it’s important to remember that almost the entire Muslim world was dominated by European countries through colonial domination for a long period of time. It’s been now several decades since they’ve emerged from colonialism, but the memory of colonialism still exists. This domination included the extraction of their resources, their natural resources, against their will. It included, for example, in the sense of French colonialism, an ideology that taught Muslims that to be truly civilized, they had to, and this is word that was being used, “evolve” into Frenchmen. The term was évoluer. And only a few Muslims could evolve into Frenchmen and really join French society. We also tend not to hear anymore, since the end of colonialism, that the colonial experience also brought with it government-sponsored missionary activity in the Muslim world, whether you’re talking about British India, Egypt, North Africa, elsewhere in the Muslim world, in which missionary activities were supported by the colonial governments, and so Muslims tended to feel under assault and under threat. You add that now to the post-colonial experience where Muslims feel the socioeconomic gap between the West and themselves. They very acutely realize that they don’t have the advantages of those who live in the West. They don’t have the governmental systems, they don’t have the resources, they’re suffering under oppressive governments. In many cases, they’re suffering under forms of government that are considered to be backward compared to other forms of government in the rest of the world. And so there’s a long buildup of anger that’s created a sort of reserve of rancor within the Muslim world. And so expressions of disrespect such as this touch a raw nerve.

And this is one reason why I think it’s so easy for Muslims to be excited or to be upset by something like that because, again, you know, they’re people who feel put upon. Since the invasion of Iraq, and of course, Iraq is not the cause of all of this stuff, but it’s just one contributing factor, since the war on terror that occurred after September 11th, 2001, going back, actually, to the first Gulf War and the first President Bush’s promulgation of the new world order, many Muslims got the idea that they’re sort of the target of the rest of the world. All eyes are on Islam, all eyes are on the Muslims, Muslims can do no right. And I think there are many Muslims who are, by nature, moderate, who may be sympathetic to some of these reactions that are taking place in the Muslim world because they feel that the bar is always being set higher, that no matter how they aspire to get to the level where the rest of the world respects them, each time they make a move up, the bar goes higher. So they have to climb another mountain or climb another set of stairs. And again, I mean, this, rightly or wrongly, this is something that one finds expressed by Muslims throughout the world from Morocco to Indonesia.

MS. TIPPETT: Muslim scholar Vincent Cornell. This is Speaking of Faith. After a short break, more of his observations. What is the line, he asks, between freedom of speech and moral responsibility in a pluralistic society? This exploration continues at speakingoffaith.org. Listen to a previous conversation I had with Vincent Cornell about the history and future of violence in Islam. Use the Particular section as a guide and download this show to your desktop or subscribe to our free weekly podcasts and listen on demand at any time and any place. While exploring, read my journal on this week’s topic and sign up for our free e-mail newsletter. All this and more at speakingoffaith.org.

I’m Krista Tippett. Stay with us. Speaking of Faith comes to you from American Public Media.

[Announcements]

MS. TIPPETT: Welcome back to Speaking of Faith, public radio’s conversation about religion, meaning, ethics and ideas. I’m Krista Tippett.

Today, “The Face of the Prophet: Cartoons and Chasm.” We’re turning to Vincent Cornell for insight into Muslim reactions to depictions of the Prophet Muhammad that first circulated in the Danish press. He condemns violent reactions. At the same time, Cornell rejects analyses that ignore the central role of the Prophet Muhammad in Muslim piety. The Prophet represents the best of Islamic faith, he says, the core of Muslim identity.

American born, Vincent Cornell is a leading scholar of Islamic spirituality and history. He converted to Islam three decades ago.

As Vincent Cornell and others have stressed in the years since 9/11, Islam is a non-hierarchical religion. This can leave Muslims vulnerable to manipulation when extremists claim authority. The Wahhabi movement associated with Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda is a small sect in terms of formal adherence but it has gained inordinate global influence. More recently, other Islamist groups have had popular and democratic successes, for example, in Egyptian, Iranian and Palestinian elections. I asked Vincent Cornell if these successes fed the volatility of the Muslim backlash against the Danish cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad.

MS. TIPPETT: Another dynamic that’s in the picture very recently is the success of Islamists in the Egyptian elections and then, of course, the victory of Hamas in the Palestinian elections, which seemed even to surprise many of the people in Hamas. Does that create an energy, a sense of power or possibility that also flows into this reaction and these protests against the cartoons?

MR. CORNELL: It’s very possible. There was an interview or part of an interview, with a major Iranian activist who was close to Ahmadinejad, the president of Iran, and this person was saying in the quotation in this article that there’s now a rising tide of fundamentalist Islam that’s sweeping throughout the world. And Hamas is part of this, Hezbollah is part of this, the election of Ahmadinejad of Iran is part of this, and so there are people, obviously, who now are feeling a greater sense of empowerment because of the victory of Hamas in the Palestinian elections. It’s probably fair to say that if there were a completely free election in Egypt, that the Muslim Brotherhood would, if not take power as Hamas did, would do so well as to probably force the creation of a coalition government. Islamist parties are, you know, despite the extremism of some of their pronouncements, are highly disciplined, they’re very focused on social justice, and so they’re popular in the same way that back in the 1970s, social gospel movements were popular in Christianity, say, something like the movements that occurred in South America, for example, you know, those sort of Marxist…

MS. TIPPETT: Liberation theology.

MR. CORNELL: Liberation theology, right, sort of the Marxist approaches to Christianity. And I think to a certain extent, this is what’s happening in the Muslim world as well. In many ways, I think if you want to look comparatively at what’s going on in the Islamic world today in terms of social movement, political movements and the aspirations of the people, if you look at places like Latin America in the ’70s, I think you’ll find an interesting parallel going on there. The difference that in Latin America, even in liberation theology, the movements tended to be more secularized than the Islamist movements areMS. TIPPETT: Well, and also, we live in an a global era, and you and I have spoken before about how globalization has given, for example, the Wahhabi movement, Wahhabi leaders have been very savvy with the tools of globalization and exert a power, have almost — you’ve said to me that they’ve kind of created the corporate brand of Islam. And it seems to me that the globalization of media has fed into these protests that have kind of echoed and mirrored each other in different countries in recent weeks.

MR. CORNELL: Well, yes, and I think, I mean, you’re absolutely right. I mean, you’re seeing right now, I think, an expression of the globalized Islamic movement, of corporate Islam in the sense that we’re not really dealing with logos here but we are dealing with slogans in the sense that defense of the Prophet becomes defense of Islam and then defense of everything that Muslims feel that they have been deprived of over the past decades. And again, and this is, you know, as many populist political movements do, you know, it creates a certain amount of profit for the religious and political leaders to whip up this kind of, and again, if I could use a comparison with earlier periods in American history, this “Know-Nothing” populism. There was a populist movement in the 19th century in the United States called Know-Nothings, of people who were largely from the countryside, you know. They were not all that sophisticated but they had basic values and basic rights that they wanted to have maintained or established. They called themselves the Know-Nothings. And in a sense, what you have here in the Muslim world is sort of a Know-Nothing movement of Islamism in the sense that these are movements that are not concerned with theological issues, they’re movements that are not concerned with spiritual issues. These are movements that are concerned with very, very sort of clear, simplistic and simplified notions of political justice and social justice, and again, I mean, are expressions of the kind of radical superficiality that I talked about in the past when we had some discussion.

MS. TIPPETT: You’ve said that you see a lot of what’s wrong, a lot of this image of Islam, of violence and terrorism and Wahhabism, as a radically superficial interpretation of what is, in fact, a very complex tradition.

MR. CORNELL: Correct.

MS. TIPPETT: But this dynamic you’re describing, I mean, it’s the comparison with Latin America in the 1970s, which we certainly saw in the Palestinian elections, Hamas’s appeal because they were taking care of people at that level of social justice. That seems to me to be — to add a layer to this. I mean, do you see that as part of the dynamic of radically superficial Islam or is that something new that may, in fact, be more powerful?

MR. CORNELL: Well, it’s not only the Wahhabis who are theologically superficial. I would say that most Islamist movements share this in the sense that theology is really not the concern. In fact, in many of these movements, there’s a sort of a mystical element. And there’s probably a whole other discussion we could have sometime about the covert mysticism that lies behind suicide — the mentality of suicide bombers. But apart from that, there’s a sense that what is fundamentally important is justice on earth. And the messages, the political platforms, the ideologies that are being promulgated by these groups are simplistic ideologies that call for very basic forms of social justice that are simply not found in most Muslim countries. What one finds is that the more social justice exists and the more fairness there is in distribution of wealth in society, that there tends to be a diminution of this kind of Islamist activity. I think this is one reason you see so much of it in the Arab world and in places like Pakistan, that have huge disparities in income.

So again, I mean, this is a valid concern. I mean, you know, everybody wants to be treated fairly. Everybody wants to have a chance to rise to a better station in life. People don’t want a glass ceiling.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, and even feed their family and, right, live in homes.

MR. CORNELL: Exactly. These are fundamental things. And so what many people do — in fact, I’ve talked to some Palestinians, for example, Palestinians who’ve been associated with the Fatah movement, what used to be the main movement in the Palestinian struggle, and these people said they voted for Hamas simply because Fatah was so corrupt that they were sending a message that, you know, somehow, they were going to be heard, that there were certain concerns that had to be addressed. And what these people did was simply choose to overlook the elements of the ideological discourse of Hamas that they disapproved of in favor of the social gospel or the social discourse that they did approve of.

MS. TIPPETT: American Muslim scholar Vincent Cornell. I’m Krista Tippett and this is Speaking of Faith from American Public Media. Today, “The Face of the Prophet: Cartoons and Chasm.”

A Pew poll conducted in the summer of 2005 showed that the general public in Muslim nations broadly shares Western concern about Islamic extremism. The poll also showed a steady decline in support for Osama bin Laden and terrorist strategies of every kind. I asked Vincent Cornell if recent controversy might result in increased sympathy for violent strategies to the detriment of both Islamic and Western societies.

MR. CORNELL: In general, I think probably not. I don’t think that the publication of these caricatures is necessarily going to increase support for extremist groups like al-Qaeda. For example, just today, a Muslim friend of mine said, you know, “I don’t know anybody who would burn a Danish Embassy.” And she also said, you know, “I can’t imagine anybody that I know who would know anybody that would burn a Danish Embassy over,” as she said, “a stupid cartoon.” You know, there are many Muslims who feel this way. You know, obviously, these — whoever drew these caricatures was trying to incite. These people probably knew that there was going to be a sufficient number of Muslims who rose to the occasion for them to be able to say, “See, I told you so.”

But by the same token, the vast majority of Muslims, even those who were offended by these caricatures, will stop and think that, “Well, you know, it doesn’t help us to have an inappropriate response,” you know, that there’s a way of dealing with this. One way, for example, is to ignore them. I mean, these caricatures came from a relatively obscure newspaper in a small European country. So one good strategy would simply be, you know, give them the attention they deserve, which is essentially no attention at all. Others would say, “Well, no, we have to do something about that because we can’t just let people insult us at will. We have to stand up and register our anger and our opposition to this, but we’ll do it in a civic way or a civil way.” That can be done as well as was done, for the most part, in Denmark. Others may say, “Well, you know, this is international and that perhaps it’s time for Muslim nations to make statements, to make strong statements saying, you know, that these kind of things should not be tolerated.”

And again, you know, freedom of speech does not mean complete license to insult and inflame. There’s a certain place where freedom of speech as, by the way, comes out in American discussions of freedom of speech, comes close to the analogy of calling “fire” in a crowded theater. So I mean, these are issues that are worked out in civil society and civic organizations, whether within individual countries, across country boundaries, internationally and globally.

We’re living in a global world and I think many Muslims, those who are considered moderate, want to be part of a globalized world. They want to be citizens of a globalized world. They simply want to be taken as equals. They have their own voice, they have their own things to say, they have their expressions, they have their desires. Sometimes, they have religious and social agendas that resonate with religious and social agendas of other traditions and other peoples. Sometimes they have different agendas. But they want to be part of the world and not marginalized and not relegated to a backwater.

So I think the mutual responsibility of both sides is to use something like this not to create violence, not to lead to killing, not to threaten people with assassination, but to use it to create a greater level of dialogue and debate. There’s nothing wrong with debate and there’s nothing wrong with people getting angry in debate. Christians have the right to be angry when Jesus is defamed; Muslims have the right to be angry when the Prophet Muhammad is defamed; Hindus have the right to be angry when someone makes fun of, you know, some image of Krishna or whatever. I mean, these are, you know — people have to be respected. If we’re going to live in a plural world and if we really want a pluralistic society, pluralism can only exist in a context of mutual respect.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, so much of the kind of reflexive response that I’ve heard among Americans has been, you know, “This is why we have the First Amendment. We have to be able to do this,” period. It’s kind of an absolute right. But I mean, what I think you’re suggesting and maybe a question that’s being raised by this, is whether pluralism, in fact, might limit some of the absolute rights that have been possible in more homogeneous and, you know, longtime democratic societies or whether, you know, whether we have to see the boundaries of those.

MR. CORNELL: I think there are two issues. There’s an issue of legal rights and there’s an issue of moral responsibility. When it comes to legal rights, our First Amendment and our concept of freedom of speech, I think, gives people the legal right even to be obnoxious, right? This is something, you know, for which people are not supposed to be prosecuted. We have the legal right to be wrong. This is very, very clear.

However, this is also a moral responsibility that is a little fuzzier than legal rights. It’s — you know, you can’t put it in a statute quite the same way. But the moral responsibility is to realize that in the United States, and this is one of the things that I particularly like about our own society and our own civic culture, I think, when — in comparison with other places in the world, is that in the United States, the ideal is that people who don’t really like each other’s beliefs have to get along with each other anyway. You know, because tolerance or you know, is not simply about people who are innocuous. Tolerance means tolerating people you don’t like or you don’t agree with or you have very, very strong differences of opinions with. Well, what that means is that to practice tolerance in this way and to allow our First Amendment protections to exist as they’re meant to exist, we have to respect these people we disagree with as human beings. And this means, you know, people do things that are strange. People do things that are excessive, people do things that are stupid, people do things without thinking, people do things for all sorts of reasons. And we can be offended by it, we can be angered by it, but they’re still people.

And again, going back to the example of the Prophet Muhammad, the Prophet’s own life was a life that really lived this ideal. He fought when the community was in danger of being destroyed. But when he had the upper hand, he was known for his magnanimity, for his generosity. He made a point of not exacting vengeance on the people of Mecca who fought against him when the Muslims eventually conquered Mecca and unified the Arabian peninsula. You know, this is the example that Muslims should follow. I mean, it’s not simply standing up for the honor of the Prophet, it’s following the example of the Prophet.

A lot of horrible things can be done in the name of honor. You know, honor itself can be a sort of an idol that people worship to the point of it leading them astray. But if they follow the living example of the Prophet, and, again, this is why it’s so important not to have superficial ideas of what Islam is about, if one follows the Prophet as the Prophet lived, then one is going to be more balanced. After all, the Qur’an itself says that Islam is adeno wasit, it’s “the religion of the middle,” “the middle way.” It’s not supposed to be a religion of extremes. And every time Muslims fall into an extremist response, they’re making themselves less as a community and as a people. They’re, I believe, anyway, they’re insulting their own religion without realizing it and they’re taking Islam away from the path that it was meant to follow.

And again, if Islam doesn’t follow the path that it was meant to follow, this way of moderation, the way of clear-headedness, the pragmatic way, the way, if you will, of sort of practical spirituality, it’s likely to fall into the same traps and the same excesses that at one time characterized Christianity and now characterized other religions of the world as well. I mean, after all, we even live in a day when you have — when one can find violent Buddhist fundamentalists. That’s supposed to be a contradiction in terms.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, there’s a paradox that strikes me as I hear you speak and it struck me at the very beginning of our conversation, when you talked about what the image of the Prophet means, not the picture image but the idea of the Prophet means to Muslims, that the Prophet represents everything that Muslims hold dear about Islam. And it struck me that the contradiction in these cartoon images of the Prophet is that, in fact, that they don’t just assail those violent expressions of Islam, in fact, they offended moderate Muslims, they offended kind of Muslims in their very being, and alienate those people from the West.

MR. CORNELL: Well, I think that’s the great danger of caricatures like these, you know, that every time something like this happens, it’s like you have a scale or a balance, you know, and you have common sense on one side and then you have the ideological pronouncements of religious activists and political activists on the other. And ordinary Muslims, normal, sort of Muslim in the street, if you can use that term, are always weighing their own common sense and their own personal understanding against what they’re told to believe on the other side. And this is why the idea that the West is out to get Islam is so dangerous, both for Islam and for the West, because each example of how the West is out to get Islam, like this, is like adding another stone to the left-hand balance of the scale to the point where eventually, the tipping point will be reached and even more moderate Muslims will come to, at least the belief, if not the realization, that, well, there is something wrong and Muslims just can’t measure up. And the only way that Muslims can possibly assert their identity is by rising up and struggling, whether it’s creating an atomic bomb or you know, rising up as a worldwide religious movement or going into terrorism or something like that.

And this is the problem. I mean, this is, again, we’ve reached, you know, for various reasons, a point today where Muslims who were willing to give the benefit of the doubt to Western philosophies, Western ideas, and Western societies, feel that the West is against them, feel that they’re not part of it. And so, you know, it’s if you don’t like me, I’ll take my toys and go home. And if I take my toys and go home, we won’t play. And if we don’t play, then we’re in enmity. And that’s exactly what al-Qaeda wants. This is what leads to the goal of bin Laden and people like that, who want to hermetically seal the Muslim world off from the West. And unfortunately, it’s happening in many ways in a de facto way, if it’s not happening in a du jour way.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, but you can’t hermetically seal the Muslim world off in Denmark or the United States. I mean, it’s not just separate countries.

MR. CORNELL: Well, yes, but you can create a lot of horror and a lot of sadness and a lot of tragedy in trying to do this impossible thing. And it’s — the Muslim world is going through its own Protestant Reformation in a way, and we see in Islam today all sorts of flowers of — and weeds popping up in the garden of Islamic expression, just as happened in Europe during the time of, you know, hate to use the term, but the Hundred Years War [sic], which is what it took to shake everything out in Europe. So you know, I’m afraid that, to a certain extent, what’s happening in Islam is something very similar, and I just hope we don’t have to go through a Hundred Years War [sic] between the West and Islam before things come back to a sense of balance.

MS. TIPPETT: Vincent Cornell is director of the King Fahd Center for Middle East and Islamic Studies at the J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Arkansas. His perspective is sobering, all the more so because he has loved, studied and practiced Islam for three decades.

Religious upheaval and reform have been bloody before, notably in Christianity’s history, but never in such an interconnected world. Vincent Cornell challenges himself and his fellow Muslims to examine their own shortcomings and prejudices and creatively rebuild and modernize the best of Islamic tradition. He leaves me to wonder how non-Muslims can support this challenge. The questions he poses cut against deeply ingrained Western civic assumptions. But perhaps we must ponder them, nevertheless. In a pluralistic society, for example, where does freedom of expression end and moral responsibility towards the other begin? How can we in the West reckon with the dehumanizing legacies of colonialism, some of which are only now unfolding? And can we find concrete ways to reconcile this together with the 1.2 billion Muslims who are members of our societies and with whom we share the world?

Continue the conversation at speakingoffaith.org and contact us with your thoughts. This week, you’ll find religious background and historical detail on Islam, as well as Web-only conversation with Vincent Cornell and others. You can listen on demand for no charge to this and previous programs in the archives section and subscribe to our free weekly podcast. Now you can listen whenever and wherever you want. You can also register for our free e-mail newsletter, which includes my journal on each topic and a transcript of each previous week’s show. That’s speakingoffaith.org.

This program was produced by Kate Moos, Mitch Hanley, Colleen Scheck, and Jody Abramson, with editor Ken Hom. Our Web producer is Trent Gilliss with assistance from Ilona Piotrowska. The executive producer of Speaking of Faith is Bill Buzenberg, and I’m Krista Tippett.

Next week, as the Enron trial continues in Houston, we’ll explore the god of business. Please join us for the next Speaking of Faith.

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.