Vincent Harding + Phyllis Tickle

Racial Identity in the Emerging Church and the World

What might words like repentance or forgiveness mean, culturally, in this moment? These are questions of the emerging church, a loosely-defined movement that crosses generations, theologies and social ideologies in the hope of reimagining Christianity. With Phyllis Tickle and Vincent Harding, an honest and sometimes politically incorrect conversation on coming to terms with racial identity in the church and in the world.

Image by Sarah Nolter/Unsplash, Public Domain Dedication (CC0).

Guests

Phyllis Tickle is founding editor of the religion department of Publishers Weekly and an authority on religion in America. She's the author of many books, including The Great Emergence.

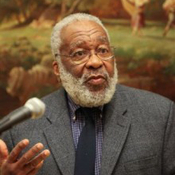

Vincent Harding was chairperson of the Veterans of Hope Project at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver. He authored the magnificent book Hope and History: Why We Must Share the Story of the Movement and the essay “Is America Possible?” He died in 2014.

Transcript

November 28, 2013

MR. VINCENT HARDING: The great American experiment with building a multiracial democracy is still in the laboratory. We have got to be willing to see ourselves as part of an experiment that is actively working its way through right now. None of us knows the answer fully, as to how we do this. We stumble. We hold on to each other. We hug each other. We fight with one another in loving ways. But we keep moving and experimenting and trying to figure it out.

[Music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

MS. KRISTA TIPPETT, HOST: Vincent Harding, an architect of the civil rights movement, sees this as a challenge for America and the Christian church. I spoke with him together with Phyllis Tickle, another religious elder, for an honest sometimes politically incorrect reflection on coming to terms with racial identity in the church and the world. What might words like repentance or forgiveness mean, culturally, in this moment? These are questions of the emerging church, a loosely-defined movement that crosses generations, theologies and social ideologies in the hope of reimagining Christianity.

MS. PHYLLIS TICKLE: There’s a difference between repentance and forgiveness and there’s a difference between those in grace. And if we do this thing that Vincent’s talking about, if we refashion this country — which we’re going to do — but if we do it without grace, it will be just as clunky and just as unfortunate. And just as many people will get the short end of the stick as has been true in the past.

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett, and this is On Being.I interviewed these longtime friends and revered elders at the 2013 Wild Goose Festival, a gathering of the emerging church. We spoke early in the morning in an outdoor tent in Hot Springs, North Carolina, in front of hundreds of people.

MS. TIPPETT: It is such an honor and a pleasure and a thrill to be here in this gorgeous place, and lets just plunge right in.

Vincent Harding was a — is a father of the civil rights movement. He followed that movement to Atlanta, helped co-found the Mennonite House there which was a heart of the philosophy and practice of nonviolence. He started the Veterans of Hope Project at Illiff Seminary in Colorado and he has spent the recent decades since the civil rights movement bringing the lessons and the legacy of what was learned there, spiritually as well as politically, to young people in the contemporary United States. And although Vincent and I had a beautiful, intimate interview, we’ve never met in the flesh, so I just was able to hug him for the first time [laughter].

Phyllis Tickle was best known when I first met her over a decade ago as the person who had really created the religion department at Publishers Weekly. But something I always also loved about Phyllis was, even though she was doing this lofty work in New York City, her permanent address was always The Farm in Lucy. Phyllis Tickle, the farm in Lucy, Tennessee.

She’s a writer and thinker in her own right on prayer and liturgy and theology. And in the cathartic autumn of 2008, she published a sweeping book about the past and future of society and Christianity, which was called The Great Emergence. Now out of the corner of my eye over this past decade, I’ve watched Phyllis become what I’ve thought of as the mother superior of the emerging church movement. I don’t know. Is that a title you would claim?

PHYLLIS TICKLE: I would love it, but I have no right to it [laugh].

[applause]

MS. TICKLE: Thank you.

MS. TIPPETT: So Vincent something you believe have been become especially passionate about, I don’t know if this has been true forever, but I know recently you’re really concerned about the opportunity we have now in this country perhaps to grow up as a democracy. I wonder how you think about what a robust Christianity has to offer, that kind of moment and that kind of task.

VINCENT HARDING: Krista, I am still recovering from the joy of seeing you in person for the first time.

[laughter]

MS. TIPPETT: That’s a way to stall, OK. [laughs]

MR. HARDING: But it’s not quite a stall and I am — I think But it’s not quite a stall and I am drinking in the beauty of being with my son and coworker here. And what’s on my mind is very close to what Sister Phyllis is talking about. I think that we are at a point where we may be ready as people of the churches to take seriously the calling that’s in the prologue to the Constitution, which says very clearly that our main job as “We the People of the United States,” our main job is not to compete with China, not to give Russia another blast from our great horns and certainly not to teach anybody else what democracy is.

But that our main job is to create a more perfect union, to develop within [applause]this country a recognition that we have been in a state of arrested development as a country. We began in a state of arrested development as a country, because we began talking about establishing freedom and democracy and, at the same time, built into our Constitution the protection of human slavery. We built arrested development into our very beginnings and it is a wonderful opportunity now for the people of God who say again and again the truth will set us free.

It is a wonderful opportunity to live that out and to go after that truth about who we really are, about where we really are and about where we need to go.I think one of the other things that the people of God have to look at is what is the difference between the emerging church in America and the emerging population in America?

[applause]

MS. TIPPETT: Um, Phyllis, your book is so brilliant and what I think is so important is you have framed your understanding of this moment in the life of the Christian church, of Christianity as a religion. And you talk — when you talk about the emerging church within that, you know, you began to see something that you call the gathering center. It’s a new center. It doesn’t look anything like the old center looked. So I’m just curious. Tell us a little bit about what you started to see, what you saw, what that looks like and how you’ve watched that emerge.

MS. TICKLE: It’s cynical, I know, but there is a certain authority to the cash register. I truly believe in the cash register and when people start spending money for stuff, it tells me that there’s something serious here.

And when the books began to go in the early 90s, in the mid 90s, and religion suddenly became — and you remember this — the best sellers, then all of a sudden Publishers Weekly, the trade journal, needed coverage of what was happening, ’cause there’d been no Religion Department. And in doing the Religion Department work, it dawned on me there is something serious happening here. We really are in a shift and we had been told that by other people, but that…

MS. TIPPETT: Joan Chittister said people started to get their church off the shelf.

MS. TICKLE: That’s right. They got their church off the shelf, absolutely. We Episcopalians have a wonderful bishop, Mark Dyer, who in 1992 started saying, “If you want to know what’s happening in the church in the world today, you have to understand that every 500 years we feel compelled to have a giant rummage sale and we’re having one.” But he’s absolutely right.

MS. TIPPETT: So tell me…

MS. TICKLE: But it’s exciting. The thing is, it’s more exciting to be in what we’re in right now — the great emergence that we’re going through is analogous more to 2000 years ago when everything shifted.

The thing we’re living in now is deeply exciting, deeply threatening and a wonderful opportunity in every way because we know where we are. Those who preceded us didn’t know. We know we’re in it and we have the opportunity and the education with which to prayerfully navigate this stream. It’s an important time. It’s a great time to be alive if you don’t think about it. [laugh]

[Music: “Dustland” by Dekko]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today: on an outdoor stage at the Wild Goose Festival in North Carolina with Emerging church Elder Phyllis Tickle and civil rights veteran Vincent Harding.

MS. TIPPETT: So, Vincent, you said you’d like us to reflect on the connection between the people of God, between this church that is emerging, and the emerging population. So I just want to invite you to flesh out that question — draw it out and give us some of your reflections.

MR. HARDING: I am very conscious both as an 82-year-old citizen and as a sometimes-historian of the American society, that we are involved in deep and powerful change, and also aware, as simply a human being, that change is frightening to many of us. And so frightening, we forget that without change there is no life.

And when I hear of the emerging church, I put it in my mind and in my heart together with the emerging American nation that is less and less overwhelmingly white. And where does the connection begin for us to think in new ways about who the people of God are.

And I think it is terribly important to keep saying to ours — it is important to keep saying to ourselves, “We have work to do.” And, I think, for the church that emerges in that kind of spirit, with that kind of consciousness, with that kind of agenda, will have a different future than the church, which does not. There is all I have to say. [laugh]

[applause]

MS. TIPPETT: Um, so I feel like you put words to some important realities that are part of this dynamic. And one thing is naming fear, which is very often inarticulate and unaware of itself, which manifests as denial or aggression. And, yet, as you also noted, this status quo — it’s not just a way of thinking and it’s not — it’s often not active, right? It’s not an active stance. It is, however, embodied. It’s embodied in our communities. It’s — this way of being is in the way we’ve all moved through the world. It’s in the world we’ve known. I think that’s such an important thing to name.

Um, what you also did, Vincent, is you posed some questions about how Christians might take up this problem, this reality, this challenge, which are very different from the way this discussion gets framed in our culture, right? You know, what I’m aware of, especially recently, is we take up the subject of race and of difference at extremely fraught moments. Right? Like the trial of George Zimmerman. We don’t know how to take up this huge exploration in an active way as an ongoing thing. So I just want to, you know — and I think I want to probe further and also pull Phyllis into this, as a white woman of the deep South, right?

MS. TICKLE: Well, what I wanted to — I totally agree with what Vince just said, except I want to say, you know, the last 50 years, um, it’s not just race. The dominance was white, male, straight. Uh, and we need to — we need to put the whole thing — the whole pot is boiling. And I know you meant that. And also the disabled, uh, who also have been marginalized in many ways, and who, in the last 50 years, are coming into their own. So what we’re talking about, I think Vince is absolutely right, is a society in upheaval.

But the point that you made that I’d really like to go to first is that much of what — if we’re not careful we’re going to end up making social policies and political policies that any good secular humanist would make simply because it makes social sense. It does not make political sense to keep somebody suppressed. It just doesn’t. Uh, it’s too expensive. It doesn’t make sense to leave the homeless out in the street. If you’re going to be just cynical about it.

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MS. TICKLE: It costs more to take care of them after they’ve caught pneumonia or whatever it is, then it would have cost to house them in the first place. So, and that’s good, communist thinking. That’s good socialist thinking. That’s good agnostic thinking. We’re Christian, and if we’re Christian, we have to go at it from the Christian point of view. We don’t have to enforce that politically. But we have to be really sure that …

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah. Like, so what is the Christian exploration? Right. So how does the Christian exploration of this reframe what’s at stake and what’s to be worked on?

MS. TICKLE: OK. So emergent sensibility needs to be definitely Christ centered. The miracles he did, the action he took — the actions he took, were all done with a loving concern for the victim, whoever the victim was, but with enormous ability to speak out to those who had victimized. Because he or she also is — and you made this point, Krista, — is to a large extent also the victim of the society which we are. It’s not as if anybody goes around, gets up this morning and say, “Boy, I’m going to be prejudiced this morning.” We don’t do that. You know, we get up and we groan and we brush our teeth and we think, “I’m going to go forth and do.” And it’s only as we become informed, about what’s going on around us and about the very things that you’re talking about, about the great emerge, our emergent society or whatever you want to call it, that we become able to understand the Christ call to both the victim and the victimizer. And I’m going to shut up, because I’m repeating myself.

MS. TIPPETT: You know, Vincent, I’d love to hear your thoughts on that.

MR. HARDING: What is the that, now? [laugh]

MS. TICKLE: Oh, you’re good.

MS. TIPPETT: Well, the idea that part of a distinctively Christian religious faithful approach to this quandary would be about a different kind of caring attention to the victimizer. I mean, it’s true that in our political life, our social life, this get’s turned — get’s — this is a discussion about —

MS. TICKLE: You probably can’t do it socially (inaudible).

MS. TIPPETT: It’s a discussion about racism, right?

MS. TICKLE: Yes, that’s right.

MS. TIPPETT: And then you’re on one side of that or you’re not.

MR. HARDING: I think the obvious approach to the question would be that there’s no way to be serious about following Jesus without calling for concern and compassion for the enemy. But immediately, as I say that, I am pushed to urge all who claim to be followers of Jesus to jump as quickly as possible from making that simply a personal kind of story, to asking, “And what does that have to do with the enemies in Afghanistan, and all over the world, that we have declared enemies? Do we want to deal with them in compassion as well? Or do we want to do them in as quickly as we possibly can?” I think that we’ve got to keep these conversations in conversation with each other, and not just have some nice talk about what we should do with those bad people over there who are doing bad things to the poor, to the homeless, et cetera, and not talk about what we as a country and what we as citizens of this country are doing to the people we call “bad guys” all over the world? So, Krista, I insist on complicating this question and not letting us get away with an easy, just strictly personal, one-to-one sort of conversation about things.

MS. TICKLE: May I just, uh, yeah, except, there’s a danger. I agree with you in theory. There is a danger, however, in taking it so global, so international that we wash our hands, congratulating ourselves on our good intentions. There is an immediacy of the problem that requires the immediacy of attention, without it’s dilution — or, dilution is not the right word. What we’re here dealing with, right here in this country, needs more immediate attention, I think, from Christians. The other, it will ripple out. If we do our job here at home, it will ripple out in who we are globally. And we — I’m not saying we should not be concerned. Obviously, we should. I deplore what we’ve done. I deplore what we’ve done for the last 15 years, maybe longer than that, internationally. But I don’t — we can divert our attention to that which we can’t fix in such a way that we don’t deal earnestly with that which we can fix, which is right here in our place.

MS. TIPPETT: Which is, I think, that’s important about keeping the conversations in conversation with each other at all times. Right. Um, so let me just ask this big question and, you know, maybe start with you, Vincent. Um, if you could give a speech to the nation, if you could wave a wand, if you could restart — I don’t want to say our discussion about this, about race, about difference, about how we’ve become a truly multicultural society — I want to say our encounter with this, um, where would it begin?

MR. HARDING: I think, Krista, that the historian in me would insist that we become mature human beings and a mature nation, rather than the kind of teenage nation, by acknowledging how we messed up from the very beginning — and not only messed up ourselves, but messed up all kinds of other people as well, including the people who used to occupy this space. I would say that I would want us, and I keep using us, I would want us to acknowledge how we got started. And to move then, not to guilt and constant talk about guilt, but move then to repentance.

And try to figure out how do we turn around from the pathway that that got us started on to the pathway of becoming loving children of God — to really go towards building a new nation with a whole new set of understandings about what is it that God wants of us. That, I think, is a conversation that would be of great help to those who call themselves Christian and those who are part of the nation that does not acknowledge that definition at all.

[Music: “Cloud 10” by Solid State]

MS. TIPPETT: You can listen again and share this conversation with Vincent Harding and Phyllis Tickle – at onbeing.org.Coming up…repentance, forgiveness, and the challenge of common life. I’m Krista Tippett. On Being continues in a moment.

[Music: “Ravenswood” by Chris Whitlley & Jeff Lang]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today I’m with Vincent Harding and Phyllis Tickle. They were invited, as wise elders, to begin each morning of the 2013 Wild Goose Festival in Hot Springs, North Carolina. Wild Goose is a Celtic metaphor for the unpredictable spirit of God. And this is a gathering of what is called the “emerging Church” – reimagining Christianity for a new moment. Phyllis Tickle is a scholar and the original religion editor of Publisher’s Weekly; she’s considered by many to be the “mother superior” of the emergent church. Vincent Harding was a leader of non-violent resistance in the 1960s and a friend and speechwriter to Martin Luther King Jr. He now leads the National Council of Elders, an organization that mentors young people and leaders, with the wisdom gained from the civil rights movement.

MS. TIPPETT: I went on a civil rights pilgrimage with your friend, John Lewis, earlier this year, with the Faith & Politics Institute. I think there’s some people from Faith & Politics here. It was an extraordinary experience. And one of the things I just began to learn, which I never really learned in school, was the gift of non-violence that that movement made to this country. And I really don’t think we have a memory of that now. What I hear you talking about is the gift of repentance that people of faith, the emerging church, could make to this nation. That’s work. And it’s also a commitment of time, right? It’s going to be generations before that kind of, uh, that is really come to fruition.

MR. HARDING: It’s going to be working generations.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah.

MR. HARDING: Not just generations, but working generations. Commitment to give ourselves fully and deeply to the task of creating something new, not just assuming that by sitting around the new is going to come. Only as we, strengthened by the grace of God, say there must be something new and we must help to embody it and to create it. And it seems to me that as we bring that faith energy to the task, then we have a new kind of situation.

MS. TIPPETT: What are you thinking over there, Phyllis?

MS. TICKLE: Oh, I’m listening. I’m enjoying. He’s two years older than I so that means I can listen to him as his …

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, he is. He’s much more mature, it’s true.

MS. TICKLE: He’s more mature. I can listen. He’s got me topped by two years. [laugh] No, there — I agree. I would put a caveat or two. My caveat, first, is that we’re post-Christendom. And that maybe is not a familiar concept to everyone, but we’re post-Christendom, in which case, uh, because of that …

MS. TIPPETT: And just say a little bit about what you mean when you say that.

MS. TICKLE: Well, it means that, basically, in 325, when the church, forgive me, got in bed with the empire — and we called it Constantine, and he was a good lover, apparently, because we sure liked him. And we stayed with him and we stayed with him until about 30, 40 years ago. It’s very dangerous for one’s soul to be part of a religion that’s socially acceptable. It just really is. And we had 1700 years of being socially acceptable. And we’re just beginning to find out what it means, um, to be a freestanding voice that can speak to the empire. We don’t have to have the president announce who’s going to be the Pope or to lay hands on the new Archbishop of Canterbury. In England, you still have to have the Queen sign of, because they’re not quite as post-Christendom as we are. So we’re tracking as two different entities, the politics and the Christian body. And increasingly, unless I’m crazy, the Christian body will become more and more of a cohesive thing, making it possible to do much of what Vincent’s talking about. And that will come through emergence. There’s no question it will.

But I think also, we need to understand that what we’re repenting for, let’s be careful. What we’re repenting for is zillions of years of not making every creature we saw a human being. And so it’s not as if the Caucasians or somebody came over here and settled this country in a vacuum. They brought with them the traditions of their culture. They brought with them all of the things that had made them. And to turn and blame bothers me. It, even, as a woman, to turn and blame men bothers me. It’s not the guys’ fault. We had a different culture. So I think part of what we have to do is begin by forgiving those who got us in this mess, realizing that it was not their mess. They became the last actualizers of it in many ways, but they were the inheritors of centuries and centuries. And until we can — I think, until we can look with grace at all of history and say, “Yes. Dear Lord I am so sorry that it was this way. I’m so sorry that my part of humanity did this to that part of humanity. But I understand, I’m not going to blame them. They, too, were the victim of a system.” Then the question becomes, so how do we make a better system so that our kids’ great-great-great-great-great-great grandchildren don’t look back and say, “Great-great-great-great-great-great grandpa was a huge sinner.” When, in actuality, he was the product of who we are and who we made him. Do you know what I’m saying?

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MS. TICKLE: Uh, we can — I’m not a feminist. You can’t have seven children by the same man and be credible as a feminist, I discovered years ago. It just won’t play in Poughkeepsie, and so — especially staying with him for 58 years. Let me tell you, it takes a lot of imagination. [laugh] Anyway, it has nothing to do with anything. But you can’t turn and blame guys for what they did to my great-great grandma, because it was a male-oriented society.

MS. TIPPETT: Mm-hmm.

MS. TICKLE: If I were gay right now, I would have to go to my prayers saying, “Please, God, let me understand that those who — ” If I were transgendered, I’d be in my prayer booth almost all day long saying, “Please, God, forgive even the gays and lesbians who are denigrating me.” You know, uh, it’s forgiveness.

MS. TIPPETT: And I think what you’re saying is really important. And, as I say, it’s not spoken, right?

MS. TICKLE: It’s not spoken. It’s not popular.

MS. TIPPETT: What you’re saying — can I say this? What you’re saying is not PC.

MS. TICKLE: That’s right. It’s not PC at all. I’m sorry. I know it isn’t, but …

MS. TIPPETT: But, no, it’s great. But what I want to — so what’s the bridge? So you — there has to be forgiveness. You know, and Vincent said this is not about guilt and blame. It’s about repentance. And so what’s the bridge between the forgiveness of that which was, of which you are a part, and being a force for creating a new world — a new reality.

MS. TICKLE:I don’t want to play at words, but forgiveness involves forgiving — repentance involves what’s happening right now and what I’m part of. Forgiveness involves the grace of looking back at that from which we’ve all come and say, “Please may it, in some way, become the ongoing part of the kingdom of God while I’m here.” And no, it’s not PC. But it true — as you can tell, it worries me. And why be 80 if you can’t say what worries you, right? There’s a certain impunity. But there’s a difference between repentance and forgiveness and there’s a difference between those in grace. And I think grace only comes in prayer, but it also comes when both repentance and forgiveness have come into full play. And if we do this thing that Vincent’s talking about, if we refashion this country — which we’re going to do — but if we do it without grace, it will be just as clunky and just as unfortunate. And just as many people will get the short end of the stick as has been true in the past. I think our only hope is prayer — we agree in every way, I think, on that — is prayer and— doing things like we’re doing right here. And also, I think, maybe talking straight.

[Music: “Fences” by Kaki King]

MS. TIPPETT: I’m Krista Tippett and this is On Being. Today on an outdoor stage with two elders of contemporary Christian life – scholar and writer Phyllis Tickle and civil rights veteran Vincent Harding.

MR. HARDING: Let me pick up from my younger sister here. [laugh]

MS. TICKLE: He is going to hold that against me. [laugh]

MR. HARDING: No, I’m going to hold it very close to me. [laugh]

MS. TICKLE: OK, that’s a deal, brother. [laugh] It’s actually two years and ten months.

MR. HARDING: Phyllis said that what we are doing here is very important.

MS. TICKLE: Yes, it is.

MR. HARDING: I’d like to encourage us, Krista, to recognize that we can’t move to new ways unless we’re willing to experiment and try out things that we haven’t experienced before.

MS. TIPPETT: And maybe failed along the way.

MR. HARDING: Absolutely. The willingness to fail is the mark of genius…

MS. TIPPETT: Right.

MR. HARDING: …because you can’t create anything new if you are tied in by this fear of failure. Wild Goose, itself, is an experiment. The idea of talking about where we might be going together with two old folks and a somewhat younger folks, sitting in front of an audience of 400 or 500 people, does that work? How is that? Well we won’t know if it works, unless we try it. Then, after this is over, as I understand it, there’s probably going to be a smaller group continuing to wrestle with these issues. I started out this morning at breakfast in a conversation with five people. What I’m trying to say is this: Please do not look for any miraculous, quick answers to how we work towards this new being and new society, which is, we need both of these things. We’ve got to figure out how we work towards them.

And I want to encourage you in a way that I was encouraged recently by one of my elders, coworkers, in an organization that some of us have begun to put together, called the council of elders. My brother wrote this letter to me and said, “Vincent, we need to keep remembering that the great American experiment with building a multiracial democracy is still in the laboratory.” We have got to be willing to see ourselves as part of an experiment that is actively working its way through right now. None of us knows the answer fully, as to how we do this. We stumble. We hold on to each other. We hug each other. We fight with one another in loving ways. But we keep moving and experimenting and trying to figure it out. I would want, more than anything else, Krista, to encourage our sisters and brothers here, not to feel that the task is so great that there is nothing we can do, but to recognize that the task is so great that we must be doing everything that we can do.

Finding a way, exploring a way, encouraging people to talk about this wherever we are. Not letting people sit down and talk about football and basketball or even church politics, without talking about this issue of how do we create a new, multiracial nation that is filled with democracy, filled with compassion, and filled with children who are coming up in a new way. How do we take all of those things on consciously, intentionally, making mistakes and, at the same time, discovering the beauty that God has in store for us? My own deepest source of strength in this is the word that most of us received from the one that we say we follow, when he guaranteed us that if we are willing to hunger and thirst for the right way, for the way of righteousness, if we don’t back off, if we don’t give up, if we don’t look for the easy way, but let the hunger and thirst really drive us, we will be filled. That is what keeps me going, that promise that if I am willing to let the hunger continue to drive my life, the filling is assured. And I have found it in many, many ways to be true. And I’m willing to go with it the rest of my life, not backing off, pushing, moving, searching, holding on to others, and seeing, as the old black song said, seeing what the end will be. And I’m looking forward to that myself right now.

[applause]

[Music: “Third” by Hiatus]

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, right. Um, I think I want to close with just one final question. I want to invoke an image that another great elder of our time, Joan Chittister, gave me. Let’s bring a Catholic voice in here. She likes to tell — I find great, great hope in this story. She talked about how she often clings to the knowledge that when St. Benedict was alive — was it fifth, sixth, century, is that right — that The New York Times equivalent of the fifth, sixth century Rome did not have a headline that said “Benedict Writes Rule.” You know? It was a little group of crazy people. I think he was — attempted, you know, one of the first communities he founded, they tried to poison him.

MR. TICKLE: Absolutely.

MS. TIPPETT: It did not go well for a lot of it.

MR. TICKLE: Absolutely. Subiaco was bad.

MS. TIPPETT: Did not go well and, you know, this group of outliers, though, created something that a thousand years later helps keep civilization alive. And I love to think about that and the fact that even I — from my vantage point with a power, you know, within media — I do not know what is happening right now in some corner of the world that’s going to keep civilization alive 50 years from now or 1,000 years from now. However …

MR. TICKLE: Hear, hear.

MS. TIPPETT: — the two of you …

MR. TICKLE: Absolutely, you’re right.

MS. TIPPETT: — and that gives me hope.

MR. TICKLE: You’re right.

MS. TIPPETT: Um, the two of you have lived a long time and you have a keen eye and ear. And I do want to ask you, as we close, you know, is there something you are watching, looking at or listening for, or looking for that keeps you going, that may not be on all of our radars? Or, you know, where would you want us to direct our attention?

MR. HARDING: One of the things that comes most immediately to my mind, Krista, is the City of Detroit, which up until yesterday morning almost, was described to us only in terms of the degradation that was going on there and all the loss and all of the blight. But for reasons that I don’t have time to go into now, I have been blessed with the privilege of actually knowing people in Detroit who have been living in hope and who have been convinced that the moment that they are living in now is a moment of great danger. and, at the same time, a moment of tremendous opportunity. And so, in the midst of the falling-apart of Detroit, there are people from a variety of motivations, including deeply spiritual motivations, who are coming together to build on that broken land — to build new settings, to build new institutions, to build new gardens, to build the lives of new children. And they are building a new Detroit in the midst of all of the stuff that we hear about the death of Detroit. Life, life, insistent life is growing up in that city. And I am personally deeply encouraged by it and keep looking at it every time I can get a chance to.

[applause]

MS. TIPPETT: Thank you. Phyllis, what are you looking at?

MR. TICKLE: Well, I, um, I think his metaphor of Detroit is absolutely. I think we can look at the church and look at thousands of groups in pubs and in old yoga clubs and in houses and, uh, yes, all over the world. Uh, there’s a meeting in a couple of weeks in Bangkok where emergence folk are coming from around the world for the first time to be able to say, “Here we are, from our various continents.” Uh, huge hope. And I would like to say, if I may, um, part of the hope for this whole thing is the fact that grandparents are here. I love looking out and seeing some white hair without having to look in the mirror to see it. [laugh] The carrying of the tradition. Let’s don’t forget that the Abrahamic tradition, the Christian tradition, which says that every human being is a human being. And that’s the fundamental thing, isn’t it? Every human being is a human. I look at you and there is Christ in you or there is a potential Christian in you or there is a flaming Christian in you. How do I know?

And the third thing is, and I think it’s probably the most important. We’ve had a — significant shift in the last hundred years as part of the lead-up to where we are right now, in which in many ways we are arriving at a completion of the Trinity. From Azusa Street and the coming of the Holy Spirit amongst those people at Azusa Street in 1907, uh, we have had the growth of Pentecostalism and of charismatic Christianity, the Renewalists they’re called, so that in many ways we now engage the Holy Spirit massively and the Holy Spirit engages us massively, in ways that, up until now, we’ve not been able to engage — corporately, we did have. But the coming of the Holy Spirit, the completion of the Trinity in the everyday practice of everyday Christians is, I think, where it is. I think that’s our seed, the thing that is going to really happen. Um, I’m not a Pentecostal, but I’m a great — I’m very aware historically. Our theology is changing as well. Or our theology is blooming. It is the same theology we had. It is now blooming and coming into fruition and maturing.

MS. TIPPETT: Yeah, you’ve both named two very important realities, that there’s life in Detroit and that the face of Christianity in this century is largely and increasingly Pentecostal.

MR. TICKLE: There are more Pentecostals in the world than there are citizens in the United States.

MS. TIPPETT: OK. [laugh]

MR. TICKLE: And if you put Pentecostals and Renewalists together, they would be the fourth largest religion in the world.

MS. TIPPETT: So I just want to say in closing that, um, sitting with the two of you has been such an important remembering that we need our elders. An important piece of truth that Western culture forgot. I mean, because — and just like — I mean, when we talk about creating a more multiracial and multiethnic society, we’re talking about becoming more whole. And I think living cross-generationally is also about becoming more whole again. It’s been such an honor. So thank you, Phyllis Tickle, and thank you, Vincent Harding. And thank you, Wild Goose Festival.

[applause]

[Music: “Book of Clouds” by Mode Fabric]

MS. TIPPETT: Vincent Harding co-founded the National Council of Elders. And he’s chairperson of the Veterans of Hope Project at the Iliff School of Theology in Denver, Colorado. He’s also Professor Emeritus of Religion and Social Transformation there. His books include Hope and History: Why We Must Share the Story of the Movement.Phyllis Tickle is a lecturer and Christian scholar and the author of nearly 40 books including The Great Emergence – How Christianity is Changing and Why. Her new book, The Age of the Spirit, comes out in January.

You can listen again or share this show with Vincent Harding and Phyllis Tickle at onbeing.org. And follow everything we do by subscribing to our weekly email newsletter. Just click the newsletter link on any page at onbeing.org.

On Being is Trent Gilliss, Chris Heagle, Lily Percy, Mikel Elcessor and Megan Bender.

[Music: “Song for Nikki” by Bonobo-trio]

MS. TIPPETT: Special thanks this week to Russ Jennings, Gareth Higgins, Rick Meredith, Brian Ammons and all of the people at the Wild Goose festival.

[Announcements]

[Music: “Seven League Boots” by Zoe Keating]

MS. TIPPETT: I love these lines from Vincent Harding’s essay “Is America Possible: A Letter to My Young Companions on the Journey of Hope.” He writes:“The dream, the seed, and the inner vision of a new nation are crucial. And all of us who are willing to hear the call are challenged to be the bearers, nurturers, and waterers of the seed of the tree of democracy that grows deep within our hearts. So the question becomes more urgent: What is the America that we dream, that we hope for, that we vow to help bring into being? If Langston Hughes (and there are many Langston Hugheses) is right, then ordinary people, bear the central responsibility for the re-creation of the nation.”

Books & Music

Recommended Reading

The On Being Project is an affiliate partner of Bookshop.org and Amazon.com. Any earnings we receive through these affiliate partnerships go into directly supporting The On Being Project.